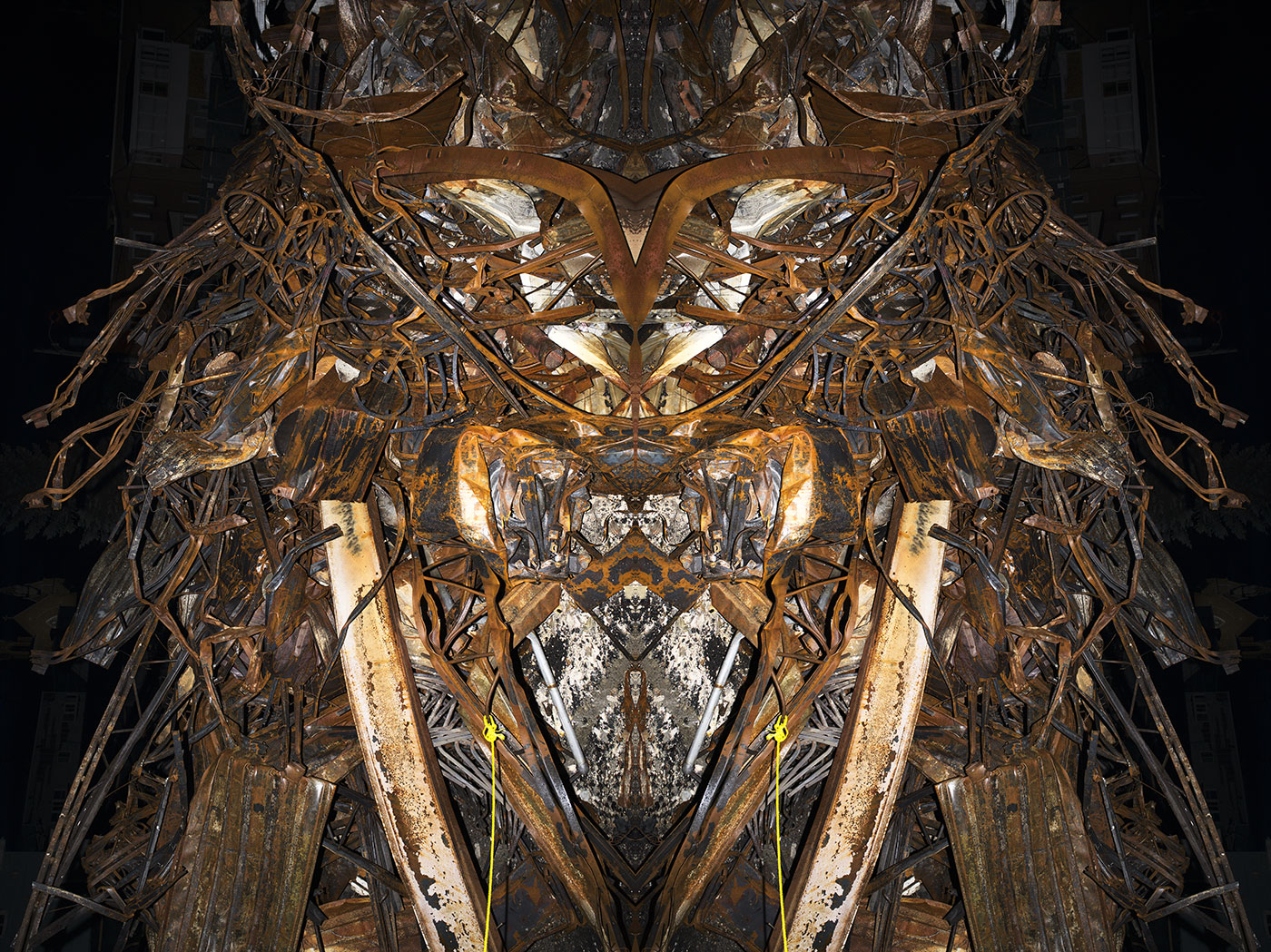

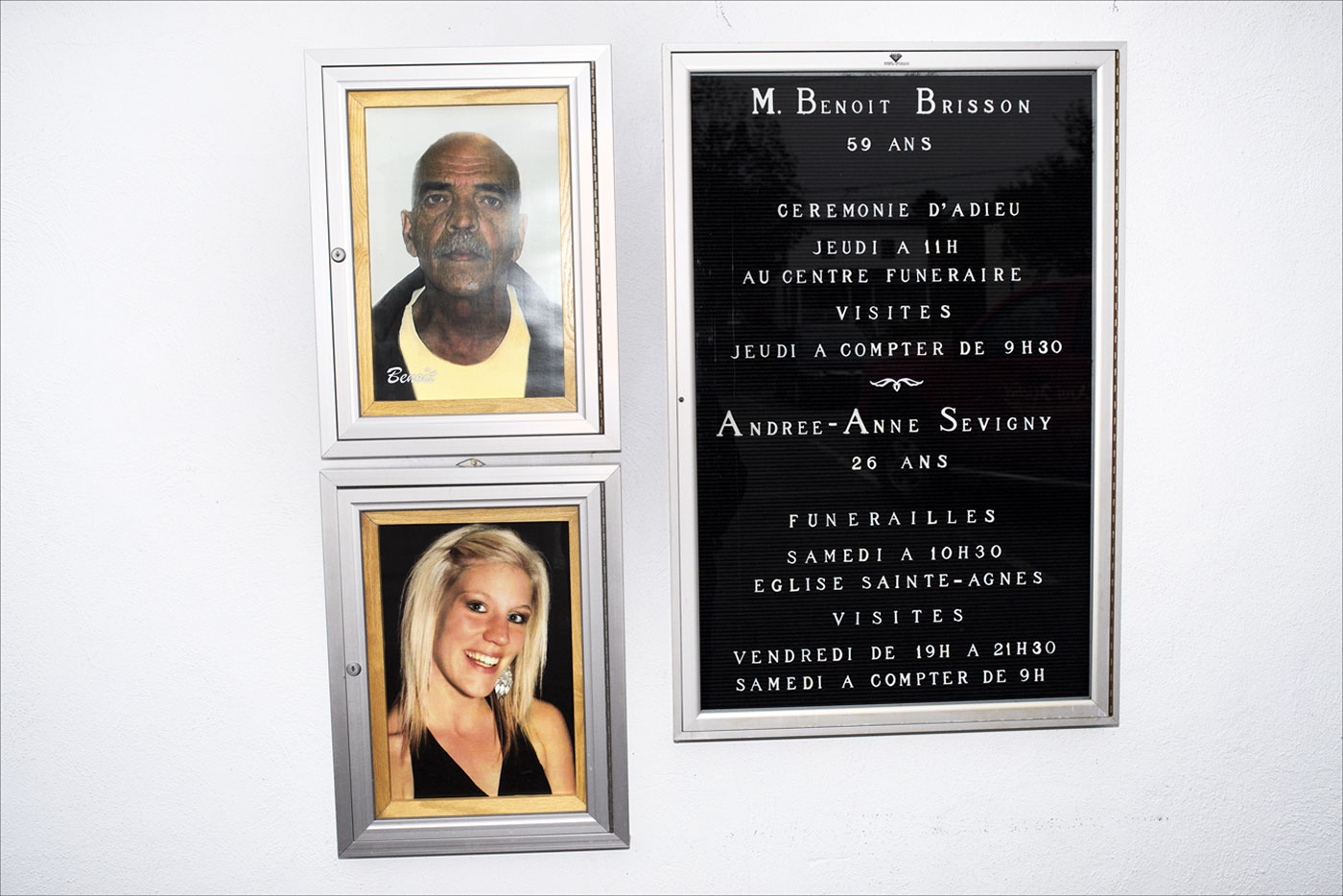

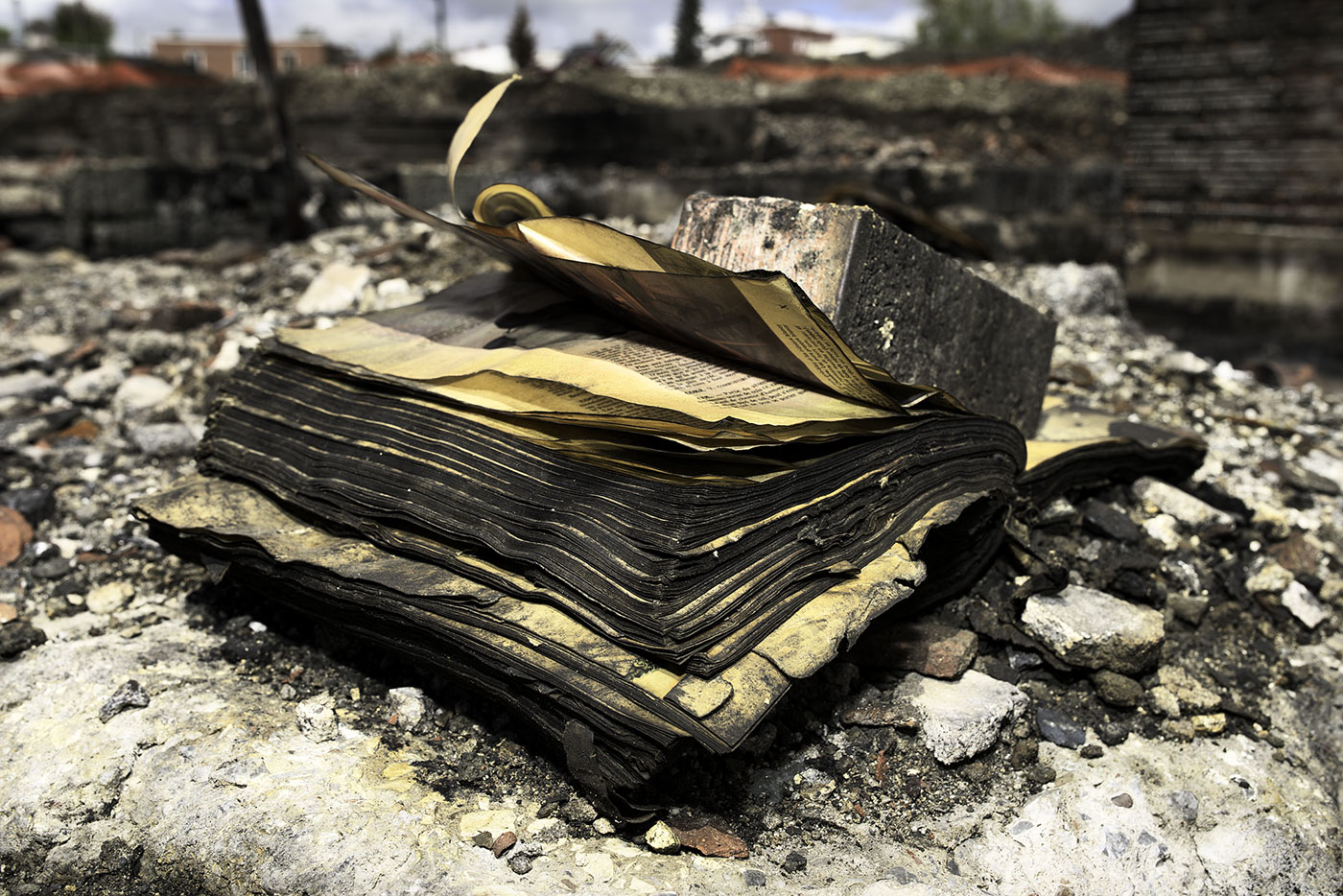

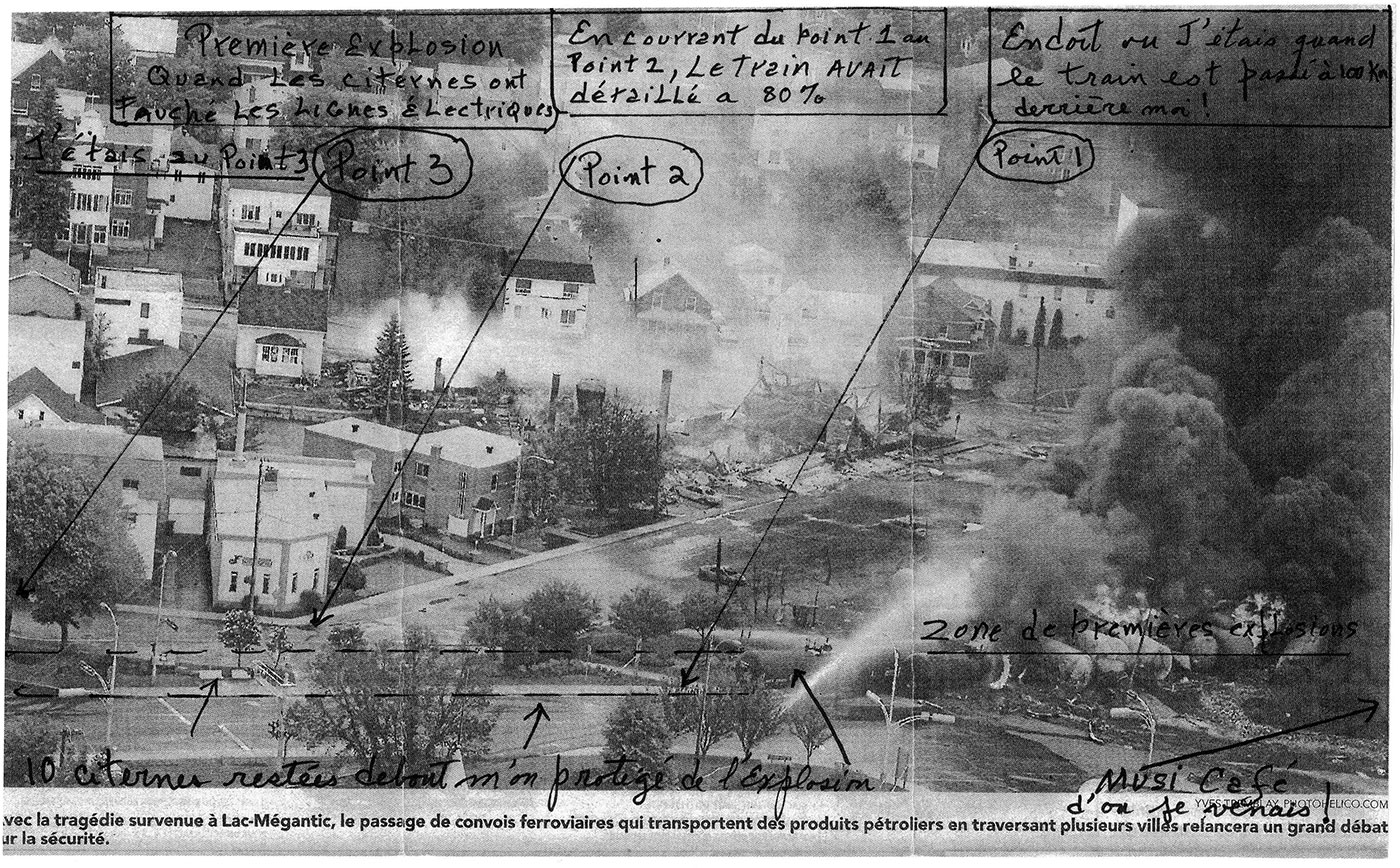

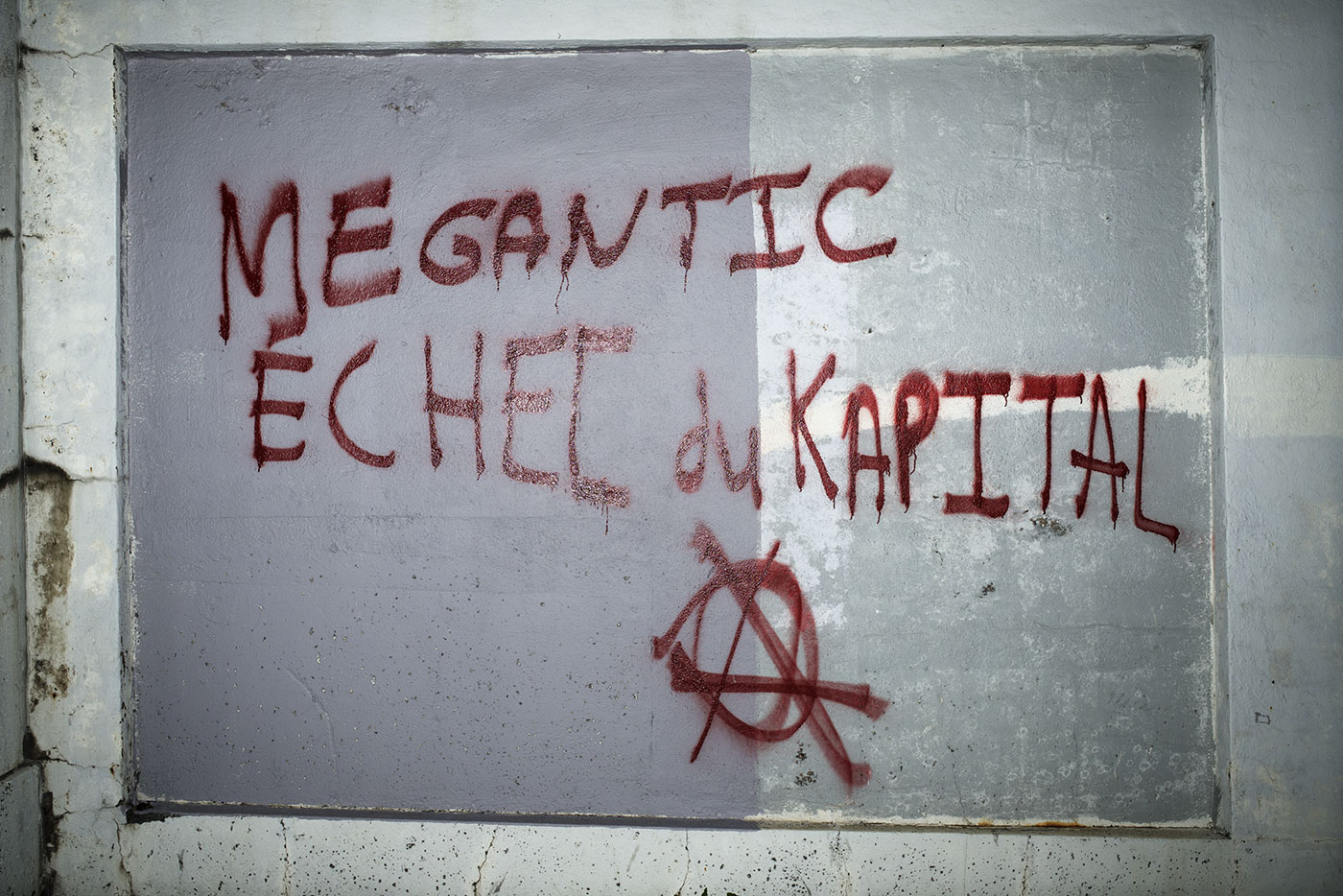

At 1 a.m. on July 6, 2013, sixty-three aging tank cars filled with crude oil derailed and exploded in the heart of Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, killing forty-seven people. A remarkable number of things had to go wrong for this tragedy to occur, and the ongoing million-dollar investigation into the company that ran the rail route raises a series of nagging questions. What if Montreal, Maine & Atlantic had used a newer, safer tank car to transport the oil? What if two engineers had accompanied the train rather than one? What if the engineer had parked the cars on the siding instead of on the main line that went through the centre of town? What if the volatile Bakken crude oil from North Dakota that the tank cars contained had been properly identified? The more we learn, the closer we come to two inescapable yet irreconcilable conclusions: this was a preventable tragedy, caused by a toxic mix of regulatory failure, greed, and human error; and it involved a cascade of freak accidents that no number of good laws or good people could have avoided.

Lac-Mégantic is a stark reminder that the world we live in is full of risk, whether the concern is oil transportation, predatory mortgages, exotic pets, or genetically modified foods. In the face of risk, we turn to regulation—and, to hedge our bets, insurance—for the optimal means of mitigating it; but the way we choose to do this says a good deal about how we view the human condition.

Let’s say we want railways to use the cars with the thickest shells rather than the older, thinner ones MMA used to move oil through Lac-Mégantic. One way of achieving this end is to require it: Transport Canada could make it mandatory that only the safest tanks be permitted on the country’s rail lines. This approach assumes that since companies seek out the most profitable, and not necessarily the safest means of moving oil, the state should make safety choices for them (or, more accurately, for us).

Approximately 80,000 of the 97,000 DOT-111 tank cars currently moving flammable liquids in North America are still of the older variety. Some rail companies are already phasing in newer cars, in response to voluntary regulations issued in 2011. In April of this year, Transport Canada announced that pre-2011 tank cars had to be retrofitted or replaced within three years. The cost could be as high as $10 billion, a massive bill that could be passed on to consumers, and could bring with it higher prices, reduced service, or both. Some observers wonder if companies will even be able to meet the government-imposed deadline, because the required supply of new tank cars does not yet exist.

This does not mean we should remove rules or soften enforcement, as in the Transport Canada decision to permit MMA to send oil transports with one engineer rather than two—something that could happen because the 1988 Railway Safety Act shifted responsibility from government to the rail companies, with Transport Canada taking an auditing role.

Deregulation became synonymous with the neo-liberal, anti-government crusades of Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and (more modestly) Brian Mulroney in the ’80s. It reflected a belief that the market could regulate itself, and that companies would strive for the best safety record (think Volvo cars) as they competed for reputation and customers. In practice, however, governments spent less money and time on site inspections and focused instead on setting standards and responding (sometimes) to complaints—at least until a public inquiry was called, as in the case of the E. coli water contamination of Walkerton, Ontario. Regulation is only as effective as the information supplied by those who are being regulated.

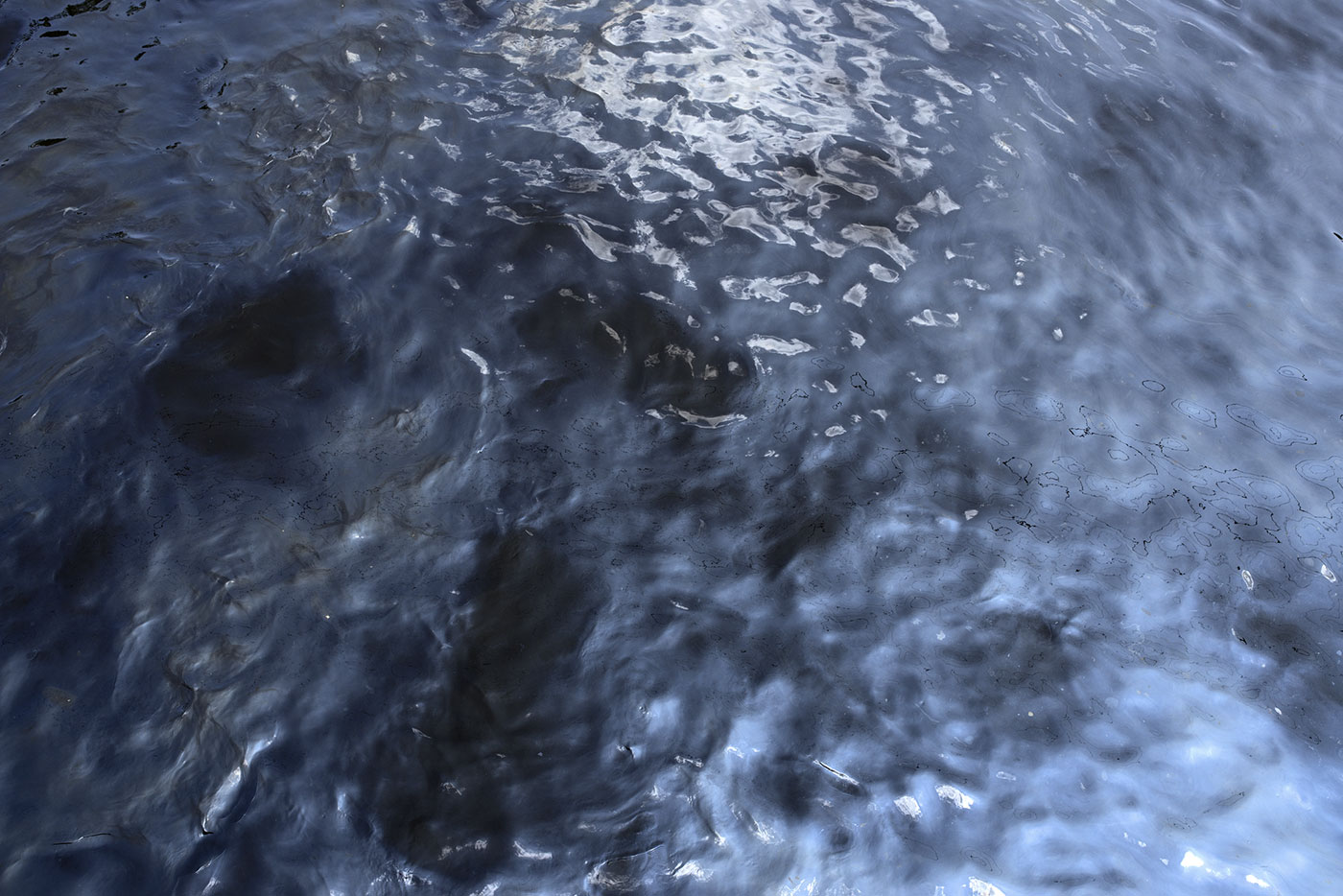

While the rhetoric of governments “partnering” with industry continues to resonate, few now take seriously the idea that we can better manage risk by empowering industry to watch over itself. Deregulation has left in its wake too many spectacular failures, including the global banking and financial collapse of 2008; the BP Deepwater Horizon explosion and oil spill of 2010; and Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011—recent catastrophes that may be tied, at least in part, to regulators whose collaboration with industry blinded them to risk.

If more rules and enforcement can be problematic, and fewer rules and enforcement could well make matters worse, how should we regulate for risk in the future? The answer, it turns out, may be more intuitive than we think. Malcolm Sparrow, professor of public management at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, likens the approach to unravelling a complex knot. Most people do not jump immediately into action. “First they hold it carefully, turn it this way and that, looking at the knot from each side, until they understand the structure of the thing,” Sparrow explained in an interview following the publication of his book The Character of Harms. “Then a plan begins to form: ‘If I loosen this strand, it will release that one, then I’ll be able to pass this through that loop,’ and so on. If they’ve understood the structure correctly, and formed the plan based on that understanding, then the knot falls apart, and is no more.”

To untangle a knot, you need both a sense of the whole problem and a sense of the right place to start. Sparrow argues that police, environmental, and transportation agencies must learn to pinpoint patterns of hazard or risk to unravel the “knots” of crime problems, environmental threats, and oil transportation. By examining specific issues and considering their structure, regulators can focus on loosening the right strand.

Rather than mandate what type of tank cars all railways must use, or how many engineers must be present on all trains, a regulator who is mindful of the complexity of transporting volatile substances might address a single strand of the problem by creating a measure to ensure that the most volatile grades of oil will only be transported in the safest cars, which would be monitored most closely where those routes pass through populous areas. This approach is alive to risk, safety, proportionality, and economic realities, imposing a modest additional cost on railways that they could more easily factor into their business model, while still addressing the risk we now know to be greatest.

Surgical interventions of this kind are more often responses to known dangers, or lessons learned from tragedies and near misses. For example, farm-to-fork radio frequency identification for cattle in Canada, introduced after the mad cow debacle of 2003, represents a successful focus on a particular strand of a knotty regulatory problem.

Sometimes the first sign of risk is tragedy itself, but what about risks that have yet to emerge, or, in the memorable phraseology of Donald Rumsfeld, former US secretary of defence, the “unknown unknowns”? Fracking may be one such example: no one can accurately predict the long-term effects of radically altering the geology of shale. Or consider the introduction of rabbits to Australia and Asian carp to North America. While the risks seem obvious in retrospect, at the time no one took them seriously.

With the “unknown unknowns,” the key to success may not lie with untangling knots, but in appointing someone to identify, assess, and consider risks to strategize their management. How will hospitals stay open and share data during the next pandemic? What will our economy look like after fifty more years of climate change?

There are always steps we can take now to better protect our communities for the future. The inherent uncertainty of risk leads survivalists to stockpile canned goods in so-called safe rooms. On a more global scale, worry about the unknowns motivated the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, which the Norwegian government constructed by tunnelling 130 metres into an Arctic mountain. When complete, it could house as many as 4.5 million seed samples from every corner of the world, safeguarded behind two security doors and two airlocks. The facility is designed to weather just about any doomsday scenario, including nuclear war, terrorists, and biblical floods.

Yet there is something futile about trying to preserve a little of everything that grows, “just in case.” Who knows what future risk this will mitigate? (Rogue asteroids, massive volcanic eruptions, and thermonuclear mayhem come to mind.) An insurance policy can provide a family with the means to rebuild a house, but it cannot bring back a destroyed home. Risk, in the end, is part of the human condition—the delicate and dynamic balance between how we shape our world and how we identify and react to forces over which we have little or no control. We mourn the tragedy of Lac-Mégantic, but we all live with the reality that something deadly might be rolling into town.

This appeared in the July/August 2014 issue.