The k43-t69 train that follows China’s great northern steppes and the legendary Silk Road could be dubbed “the desertification train.” Travelling from east to west, from Beijing to Urumqi, it cuts through 3,343 kilometres of dusty grasslands, dried-up riverbeds, threatened oases, and deserts both ancient and new. A few hours after the train leaves Beijing, a lunar black mountain range welcomes passengers into a vast arid landscape.

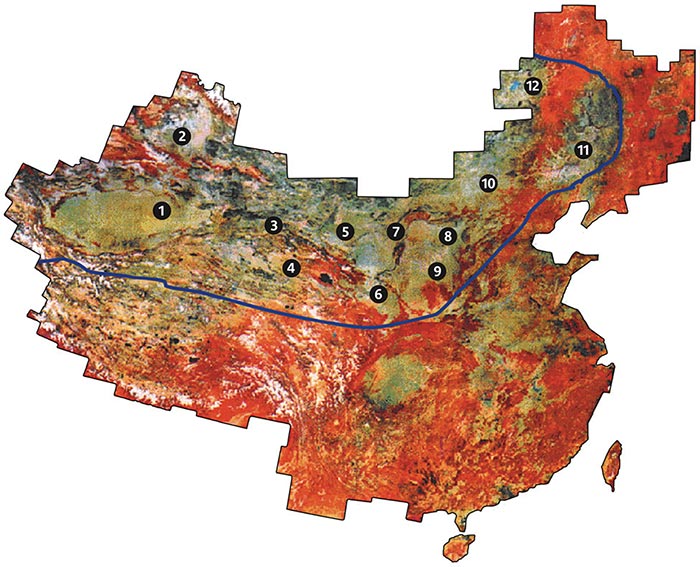

Deserts cover 18 percent of China today. Of those, 78 percent are natural, while 22 percent were created by humans. Almost all of them lie along the k43-t69’s route through the provinces of Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Gansu, and finally Xinjiang, at the edge of Central Asia.

Lulled by the rhythmic clang of metal wheels on rails, for two days passengers can watch a dreamscape of steppes and deserts go by. But the view also reveals one of the greatest environmental disasters of our time: the Chinese Dust Bowl, probably the largest conversion of productive land into sand anywhere in the world.

To date, Chinese farmers and herders have transformed about 400,000 square kilometres of cropland and verdant prairie into new deserts. The shepherds have overgrazed the steppes, allowing their sheep and goats to chew the grass all the way down to its roots. The farmers, for their part, have over-exploited the arable land by opening fragile grasslands to cultivation and over-pumping rivers and aquifers in the oases bordering the ancient deserts. The area of desert thus created is equivalent to more than half the farmland in Canada.

The soil, once it is barren, is swept up by the wind into dust storms, battering the capital, Beijing, and then moving on to Korea and Japan. The most massive of the yellow clouds of dust make their way across the Pacific and reach North America. The loss of precious topsoil for Chinese agriculture ends up polluting both China’s cities and countries halfway around the world.

The North American “dust bowl” of the 1930s forced three million farmers to abandon their land in the Midwest and the Canadian prairies. But the Chinese exodus could reach well into the tens of millions. Governmental relocation programs for ecological refugees are already in full swing.

From their choice vantage point at a window seat in the k43-t69’s upscale restaurant, train passengers can witness another equally spectacular sight: everywhere on the horizon, scores of men on old three-wheeler trucks wield shovels, tree seedlings, and shrubs. All over the desert, unnaturally straight rows of trees now stand against the wind. The k43-t69 also overlooks the greatest environmental restoration effort in history.

Since 1978, Chinese forestry engineers have been supervising the planting of the Great Green Wall. Some 4,500 kilometres in length, the tree barrier is intended, when completed in several decades, to prevent desertification by protecting the fragile land from wind.

Another project of equally immense proportions is the South-to-North Water Transfer. It aims to redirect to the north, by the year 2050 via a network of canals, about 50 billion cubic metres of water per year from the rivers of southern and central China. The project will obliterate heritage sites and engulf villages and towns.

The international community is fully on board: the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the United Nations, Germany, Belgium, the United States, Australia, South Korea, Italy, Japan, and Canada are all participants in the Chinese scheme to save its soil, either through funding or by sending experts and scientists.

Despite remarkable local achievements, overall desertification in China remains uncurbed. In 2006, there were seventeen dust storms, the worst of which dumped 330,000 tonnes of dust on Beijing in one night.

After travelling 500 kilometres, the train slides into Jining South station. This marks our entrance into the expanse of China’s Inner Mongolia Province, once famous for its lush steppes and the shepherds who inhabit them. Today, though, it is becoming famous for its new deserts.

In 2001, former president Jiang Zemin passed the Law on Desert Prevention and Transformation, and, in 2002, the new Grassland Law. Both forbid grazing during critical periods like spring. Parcels of land are fenced off and protected for natural restoration, but despite the law, as our car goes up a hill, a herd of sheep appears out of nowhere, munching on the steppe’s exhausted turf. Two shepherds greet us with a mocking gaze: “We let our herds onto the pastures at night, when the police knock off,” one explains from under an oversized fur hat.

Our conversation is suddenly cut short as they push their flock into the valley, having spotted a police car coming down the road. “The grass police!” one exclaims. It is only as we head back to our taxi that we notice the mass of sheep excrement underfoot.

The next morning, we drive on the new highway through kilometres of sandy land before reaching the prairie around Xilinhot City. Mongolian herders on motorcycles direct their horses through denuded dales, but the majority of the people we cross paths with are workers, busy planting yellow willows in an effort to keep the dunes in place.

“Most of these tree planters are herdspeople,” explains the foreman. “They now keep their animals in pens. The government compensates them for their losses and provides them with forage. The herders end up making more money!”

Farther off, there’s a mechanic’s shop, where shepherds wait for their motorcycles to be fixed. “The restrictions aren’t good for the shepherds,” says the only one among them who speaks Chinese. “The sheep that these Mongolian herders keep in pens lack food. They’re too thin. That’s why many hide from the police to let their animals graze at night.”

From a mere 2 million in 1977, the number of animals grazing the Xilingol steppe had reached 18 million by the year 2000, expanding the Hunshandake desert and desertifying the steppe itself. Local governments encouraged breeders to raise their livestock numbers in order to pump up this desolate province’s gross domestic product. In China, officials are promoted or sanctioned based on their success in increasing their regional gdp.

On this morning the sky is blue. Until 11 a.m., that is, when a cloud of dust from the steppes surrounding Xilinhot City moves in, visible in the distance from every alleyway. The sand beats against the car windows as noisily as a hailstorm. “We have to replace our windshields once a year,” complains our driver. Despite the wind and the sand in their eyes, teams of tree planters continue their arduous task.

At 1,335 kilometres from Beijing, the train reaches Yinchuan station in the Muslim-dominated Ningxia Province. This is where the great Mongolian steppes give way to the ancient deserts of western China.

Hongsibao and its forty-two satellite villages were created from scratch eleven years ago. Previously, only the cannons of the People’s Liberation Army rolled over the soil of this immense gravel expanse. Since then, Hongsibao has become the largest city of ecological refugees in China, inhabited by 200,000 peasants and herders moved there from the dry mountains.

Hongsibao is the jewel of what the Chinese government calls “ecological construction.” This consists in reshaping the country’s landscape to save endangered ecosystems and lift out of poverty the millions of Chinese left behind after thirty years of economic boom.

Ecological construction can take one of two forms: either the authorities close fragile ecosystems to human activities, returning them to nature by creating protected areas, or engineers construct entirely new agricultural ecosystems by pumping in water from the Yellow River, which traverses the northern deserts and steppes. But the once-mighty Yellow is now at risk of not reaching the sea anymore as a result of excessive pumping and climate change, so the engineers are designing a system of canals that will fill it with water redirected from the Yangtze River, which floods the south of the country.

The view along the road to Hongsibao is so desolate that it is hardly surprising to see a prison set up on its outskirts. With its air of a company town, Hongsibao has everything: a wedding dress shop and one for designer jeans, a “one hour” photo lab, a huge market square with open-air billiard tables strangely wrapped in plastic sheets, an enormous Soviet-inspired plaza illuminated by postmodern streetlights. There is even a two-star hotel where officials receive generous foreign donors.

In Mrs. Ma’s courtyard, copper-cheeked children jump rope. This new Hongsibao resident recalls, “In the mountains, we had to rely on the Old Heaven for water!” She has been an ecological refugee since her village was deemed part of a protected zone. “I miss the mountains’ panoramic scenery. But we prefer our new house,” says the former cave dweller. The UN has classified her native region as one of the most inhospitable to human life on Earth. People are said to bribe officials to be registered on the lists of displaced people.

Outside, a dust storm rises, paralyzing Hongsibao as well as the rest of the northwest all the way to Beijing, a reminder that ecological construction hasn’t been achieved yet.

Back in Inner Mongolia Province, along the Alashan Left Banner route, hundreds of kilometres of fences prevent access to pastures. Mud huts where shepherds once lived are falling into ruin.

The local government is currently carrying out a large forced resettlement operation there. The objective has been to move 80 percent of the region’s shepherds—40,000 in total—from the degraded prairies to artificial oases (where they are taught how to raise cows and grow vegetables) between 1989 and 2010. In front of one model village, a billboard announces, “For people resettled due to the ban on grazing, 20 million yuan [$2.8 million] were invested to build greenhouses, paddocks, barns, and houses.”

A woman on the main street refuses to give her name, much less agree to be photographed, but she is willing to speak. “The ban on grazing should last five years,” she says. “We receive subsidies while we wait. But we’re afraid of not recovering our land after the ban.”

Then a young woman arrives on a motorbike. It is 10:30 in the morning, and she invites us for lunch. That’s when officials from Alashan’s propaganda department rush in. The invitation is a trap.

The chief is outraged: “What are you doing on my territory without permission? You’re violating the Chinese constitution!” But then the “public relations officers” take us to lunch in the best restaurant in town before escorting us directly to the long-distance bus station.

On a road that penetrates deep into the undulating steppes of Siziwang, the coordinator for the small ngo Friends of the Grasslands, Na Ren Gao Wa, guides us to a voluntary resettlement project that looks like a ghost town.

Only a few retired people live in the brand new village. In one of the eight small, inhabited houses, we find Mrs. Su Mu Ya perched on a kang, a platform that northern Chinese people eat and sleep on. “The shepherds came here, tried to raise a few cows, and rapidly returned to their dusty grasslands,” she says. Her son stayed on the family rangeland with all the animals.

“This resettlement of displaced herders shows the failure of the ecological migration policy in Inner Mongolia,” Na Ren Gao Wa insists. Based on field research, the ngo has concluded that plans that do not take into account shepherds’ views and traditional knowledge don’t work.

The roadside landmark that guides us to Mr. Zhao and Mrs. Xue’s house is easy to see: a collapsed restaurant half-buried by a sand dune. “During the worst year, eighty of our two hundred sheep died of hunger,” recalls Mrs. Xue. “But we prefer staying here to resettling in one of those new milk production villages. Cows cost 9,000 yuan each ($1,250). They require a lot of care, like children!”

At 1,740 kilometres into the k43-t69’s trajectory, we hit Wuwei City, the stop for the Minqin oasis in Gansu Province. Scientists, politicians, and journalists congregate in Minqin because it symbolizes China’s battle with desertification: the small agricultural enclave housing 300,000 is now threatened by the spread of the Badan Jaran and Tengger deserts, two natural deserts that are slowly meeting in the middle.

The first thing that strikes any visitor to Minqin is the buzzing sound made by the diesel pumps that are located at the four corners of the oasis. They are drawing water from the subterranean water table in order to redirect it to vast fields of corn, wheat, and watermelon.

Leaning on a shovel, Xu Li Qing, a farmer, justifies the operation. “We pump water from underground because the river that used to feed the oasis has dried up. But within twenty years we’ll have used up all the water in the soil,” he admits.

Farmers in Minqin have extracted so much water that the underground water levels have dropped by more than twenty metres, out of the reach of tree roots. Since 1965, no fewer than 10,000 wells have been dug. Through this practice the farmers have driven two-thirds of the oasis’s natural plant life to extinction. Winds were free to blow the light topsoil away, leaving only the coarse sand.

The Forestry Bureau planted a protective belt of trees around the oasis, and the central government financed an aqueduct to bring water in from the Yellow River, channelling it through a hundred kilometres of dunes. But the authorities have now agreed to drastic measures: up to 150,000 ecological refugees will be transplanted from this fragile ecosystem within the next twenty years.

Many of the stakeholders involved in the fight against desertification in China, both foreign and Chinese, are calling for investment in a more promising strategy: conservation agriculture, designed around water-saving irrigation systems, more suitable farming and grazing practices, and the inclusion of farmers in the decision-making process.

“China must invest more in its number one resource: its farmers and herders,” advises Brant Kirychuk, manager of a project led by Canada’s department of agriculture in the arid northern provinces of China. “They need to be guided and then take part in decisions.” Between 2000 and 2009, the Canadian government has committed $23.5 million to a sustainable agriculture plan aimed at rejuvenating China’s arid lands. Canadian experts are on hand with Chinese specialists as well as with farmers and herders to share a process that was developed to save the Canadian prairies from the 1930s dust bowl. “In Canada, thirty years were necessary to recover,” Kirychuk says.

Around 10:30 a.m. in the Wuwei oasis, the wind forms a dust storm spiralling over a dried-up reservoir. In the yellow mist, farmers try to find their way home on their motorcycles. In the car, meanwhile, our discussion continues with the local who is guiding us through the wretched province of Gansu. “People surreptitiously continue to cut down trees, despite the fines,” he confesses. Outside, the wind is robbing the country of another precious layer of arable land. When all the earth is gone, it will take at least 200 years for the fertile soil to re-form.

Before arriving at its final destination, the Urumqi train station, the k43-t69 might well have been stopped in its tracks by yet another blinding dust storm. If that had happened, at least its passengers would have had the opportunity to reflect upon the monumental challenges facing the Chinese people as they continue to fight to save their land.

This piece was produced as part of an ongoing project supported by the Canadian International Development Agency.