Anne Carson, the Toronto-born poet, professor, essayist, classics nerd, and wilful eccentric, has dedicated no small part of her career to reconfiguring ancient myth. Actually, “reconfiguring” just grazes the surface. Let’s try “reinventing,” or “revitalizing,” or even “reframing our understanding of the past by envisaging millennia-old tales as they might play out in a world very much like ours.”

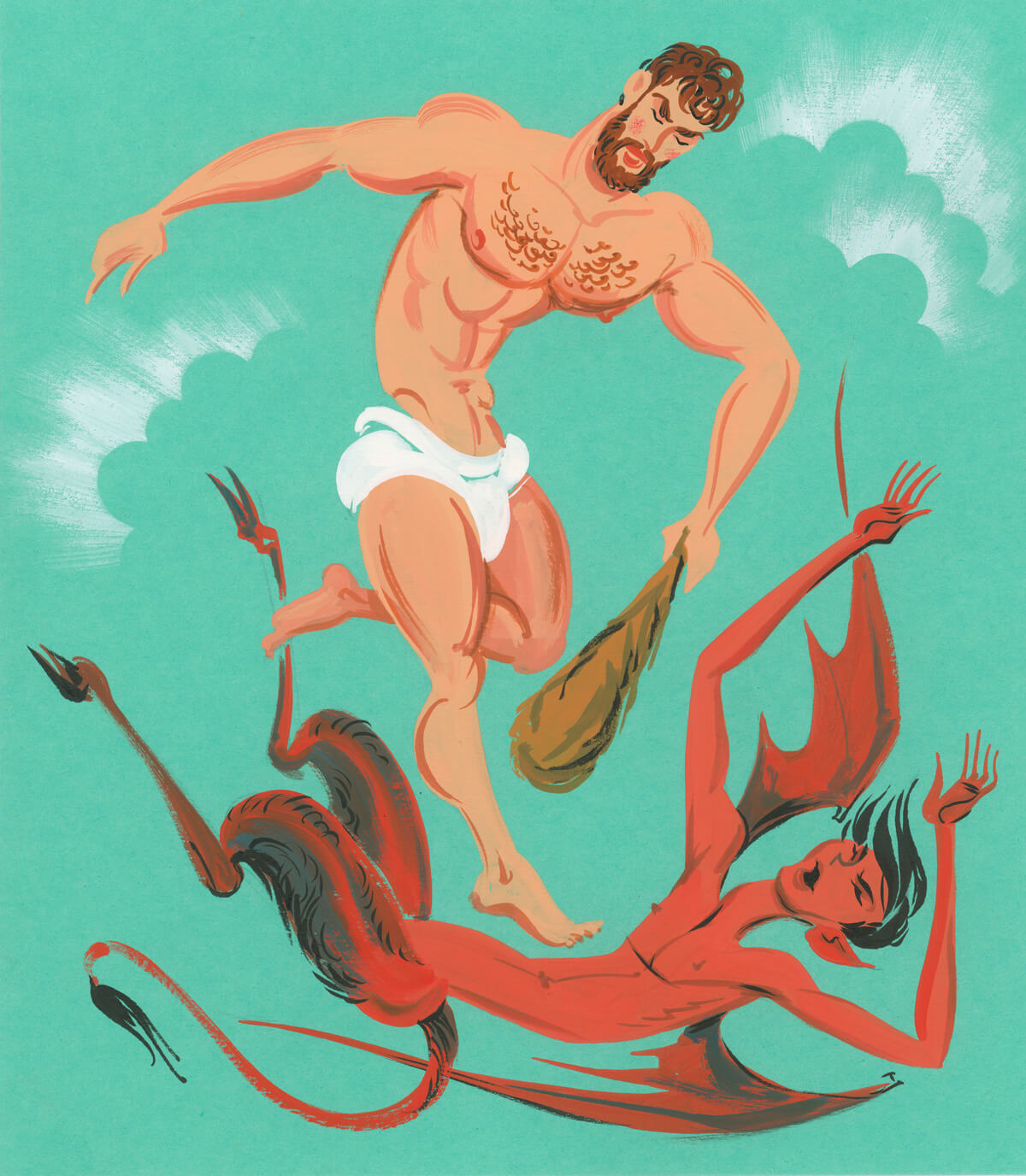

She has revisited classical tragedies by Euripides (An Oresteia, 2009) and Sophocles (Antigonick, 2012), peppering her English translations with unexpected nods to modern works. She has stitched together fragments by the Greek lyric poet Sappho, for her books Eros the Bittersweet (1986) and If Not, Winter (2003). But her best-known work is Autobiography of Red, published in 1998. This novel-in-verse pries a minor episode of Greek lore from between the clenched jaws of history. Based on the twelve mythic labours of Hercules, the story narrows in on the tenth task, in which the hero must steal a herd of red cattle from the monster Geryon, killing the beast in the process. In her telling, the author reimagines the narrative—conquering hero slays grotesque fiend—as a contemporary queer coming-of-age story. From the underdog’s perspective, Carson, advocate of the abject, describes how Herakles (a variation on the Greek name) coolly crushed the heart of the red-winged monster.

Lit world titans gushed over Autobiography of Red (Susan Sontag: “spellbinding”; Alice Munro: “amazing”); it earned awards and accolades (Carson won a MacArthur Fellowship after its publication); and she became that rarest of rare things, a bestselling poet. A glowing 2000 New York Times profile claimed the book had sold 25,000 copies. It was not just popular; it was populist. Carson became a fleeting plot point in the pilot of the soapy, Sapphic Showtime drama, The L Word, in 2004: “Those books practically changed my life,” stammers a drippy writer to her seductress, alluding to Autobiography of Red and Eros the Bittersweet.

Given this, Carson’s decision to produce a sequel, entitled Red Doc>, more than a decade later should come as no surprise. (Though it does. Multiple instalments are the stuff of Star Wars and Harry Potter, not volumes of poetry.) “Some years ago, I wrote a book about a boy named Geryon who was red and had wings and fell in love with Herakles,” she says in the book’s press material. “Recently, I began to wonder what happened to them in later life. Red Doc> continues their adventures in a very different style and with changed names.”

In Autobiography of Red, she updated a myth to tease out underlying qualities of ancient Greek culture—its embrace of same-sex relationships, for example—that struck a chord in modern times. In Red Doc>, she revisits these characters, outside of their prescribed plot line, to ask what happens when the same old story will not suffice. The answer, as you might imagine, is complex.

A Distinguished Poet-in-Residence at New York University, Carson studied classics at the University of Toronto, with a brief detour at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, earning a BA, an MA, and a Ph.D. Her doctoral thesis, a rumination on the poet Sappho, later morphed into Eros the Bittersweet. U of T also awarded her an honorary degree last November, in a curious ceremony during which she appeared to be wearing a woollen aviator’s helmet. She is a translator of words and ideas by trade and by instinct, and her project involves matchmaking between classical and modern languages, texts, and meanings.

To be sure, she is not the only contemporary writer to use the distant past to explore the present. Margaret Atwood, for instance, reframed The Odyssey as a misunderstood wife’s tale in her novella turned play, The Penelopiad, seeking to shed light on women relegated to the darker corners of ancient lore. Carson’s work, though, has a unique vitality, in part because she embraces unorthodox tactics.

Autobiography of Red’s puzzle pieces are fragments of an actual ancient poem, the Geryoneis (“the Geryon matter”), by Stesichorus, a Greek lyric bard who lived sometime around the sixth century BC. The original sketches out the life and death of Geryon, a formidable giant with six hands, six feet, several bodies, and great wings, who tended cattle on the red island of Erytheia, until he was killed by an arrow to the head by Heracles (another variation on the name).

In Carson’s story, which is told in un-rhymed prose poetry, Geryon is a hybrid of boy and beast. His monstrosity is his sense of otherness, his awareness that he is gay, and his sordid, secret shame. His colour and wings are symbolic, but they also constitute marks of his difference that he tries, and fails, to mask. “Hand in hand the first day Geryon’s mother took him to / School,” Carson writes, “She neatened his little red wings and pushed him / In through the door.”

From the current cultural vantage point of Lady Gaga, gay marriage, and the It Gets Better Project, we must remember that when Autobiography of Red was published in 1998 sexual otherness was still fraught. In the US, the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell military policy was in effect. Ellen DeGeneres had come out just the year before. And some six months after the book’s publication, a young gay man named Matthew Shepard left a bar with the wrong guys and was tortured, tied to a fence, and left to die in a Wyoming field.

Carson’s message, however, is not simply about sexuality, but rather about otherness in general. She is straight—at least, sort of. In a 2004 interview in The Paris Review, she alludes to her “somewhat checkered career as a gay man,” and notes that she grew up fixated on Oscar Wilde. “I wouldn’t say I exactly felt like a man,” she says, “but when you’re talking about yourself you only have these two options. There’s no word for the ‘floating’ gender in which we would all like to rest.”

She is deliberate in casting Herakles as both gay and flawed. If the character of myth was defined by his feats of physical prowess and strategic dexterity, her champion prevails because he refuses to let messy, unwieldy emotions get in his way. Meanwhile, heartache and self-loathing knock her Geryon’s knees out from underneath him. Yet he is the one who witnesses and documents moments of exquisite beauty. At least, this is the dynamic that plays out in their heady, impressionable youth.

Red Doc>, another novella-length poem, is set an indeterminate number of years later, in a contemporary but surreal pastoral world. Geryon, now grown and worldly, is known as G. He oversees a flock of oxen that grazes on a high, gorse-covered hill. In the manner of well-meaning straight people since the dawn of time who just know their two single gay pals were meant to be together, his friend Ida, an eccentric artist who shares a name with the birthplace of Zeus, helps to orchestrate an encounter between him and her brooding, troubled buddy. Turns out the two don’t need a go-between: Ida’s friend, a fellow named Sad But Great, appears to be Herakles, brandishing the sobriquet he was given as a member of the modern-day military. Sad is not just sad but shattered, struggling to cope with post-traumatic stress disorder. He and G have not crossed paths since they extricated themselves from their tumultuous romance.

A sense of blurriness permeates the book—in part, it seems, to mimic the experience of returning from battle. G lives in a rural enclave, but Sad and Ida spend much of their time in a mental health facility, where Sad gets pills, Ida gets supervised, and G gets drawn into their disjointed world. The narrative is punctuated by a Greek chorus, and bookended by the decline and eventual death of G’s mother, whose chain-smoking permeated Autobiography of Red.

That glimmer of continuity feels like a cairn left behind for the first book’s cultish devotees. Although Carson introduced these figures—the red-winged monster, Geryon, and the fated hero, Herakles—as having been ripped from ancient history, destined to fulfill the symbolic roles mapped out for them centuries ago, that storyline has already played itself out. “To live past the end of your myth is a perilous thing,” she says cryptically in the book’s press material.

But what does she mean by that? French literary theorist Roland Barthes (and generations of semiotics students who followed in his footsteps) has argued that myth has the effect of making ideologies seem natural, always-already there. The very nature of an archetype is that it repeats and echoes through time; cultures gravitate toward particular stories, depending on their priorities at a given moment. The cartoon The Mighty Hercules, for example, which introduced me to the Greek demigod when I was a kid, was produced in 1963 as an analogue to mid-twentieth-century sword-and-sandal films. Those movies were themselves an attempt to reiterate comforting moral certitudes (good trumps evil), and to assert a beefy version of traditional masculinity in the face of the nascent women’s liberation movement. Even so, a sly, camp frisson of homosexuality bubbled just beneath the surface.

This repurposing of the past in concert with the needs of the present does not apply exclusively to “myth” in its most formal sense either. In a recent essay in The New Yorker, the writer and critic Daniel Mendelsohn, who is gay, describes how, in the mid- to late ’70s, he became consumed by the fiction of Mary Renault, a novelist whose stories sketched out same-sex love stories in antiquity. “Reading Renault’s books,” he writes, “I felt a shock of recognition. The silent watching of other boys, the endless strategizing about how to get their attention, the fantasies of finding a boy to love, and be loved by, ‘best’: all this was agonizingly familiar.” That this narrative of homosexual attraction was taking place somewhere around the fourth century BC, provided a touchstone. Perhaps Mendelsohn was not alone—or wrong—in his desires.

Carson is not the least bit atavistic: the more you read, the more you appreciate her gift for crafting electrifying poetry through an aggregation of bits and pieces, from the New Testament to Goethe to Proust. It is an acknowledgment that the stories we have told one another for centuries still resonate, even if their meanings have changed. Or, to borrow a line from Julian Barnes’s 1989 collection, A History of the World in 10½ Chapters, “The point is this: not that myth refers us back to some original event which has been fancifully transcribed as it passed through the collective memory; but that it refers us forward to something that will happen, that must happen. Myth will become reality, however skeptical we might be.”

However, it is challenging to contemplate where to go if there is no obvious precedent. When, early on in Autobiography of Red, Geryon begins to write his life story, language is not enough: one self-portrait consists of a tomato with “crispy paper” hair. This failure of conventional methods to tell the story of someone not quite “normal” echoes Carson’s artfully incongruous, pieced-together narrative. If the dominant lexicon offers no options to describe what you are, you are forced to make something up. This idea recurs in Red Doc>, in which the stepping stones of myth no longer suffice, and that narrative breakdown could serve as a defining symbol for the twenty-first century. Traditionally, we looked back to understand how we should move forward, seeking a moral code as well as a moral codex in the epic quandaries of the gods (what would Zeus do?). But culture now accelerates at such a breathtaking rate that the old absolutes have become less certain. Consider the dizzying evolution of our vernacular, or our communication etiquette, or our legal system, over the past two decades. It seems perilous to have exhausted the usefulness of our archetypes, and to face the prospect of establishing new guiding principles.

With Sad But Great, Carson wonders what befalls the warrior after he has completed his trials. Once he has vanquished his foe, she suggests, he is left to contemplate the aftermath of his carnage. For G, the hapless beast whose downfall seemed inevitable, she asks what would transpire if the monster came to terms with his own monstrosity, and how he would cope if his brush with Herakles was neither fatal nor his gravest challenge. What then? Myth is not good at addressing hypotheticals; it presents plot as fact, with no wiggle room for alternate possibilities.

In a 2003 interview with the academic journal Canadian Literature, Carson highlighted one idiosyncrasy of the ancients. “Lying and error are the same word for the Greeks, which is interesting,” she said. “That is, ‘to be wrong’ could have various causes: you wanted to lie, or you just didn’t know the truth, or you forgot—and those are all one concept.”

In Autobiography of Red, she presented us with the facts: Herakles slew Geryon, if not by physical force, then through the violence of breaking his heart. The former continued along his course, unbothered; the latter stumbled along, scarred, and was never quite the same. In Red Doc>, Carson reveals that the facts don’t tell the whole story: that myth, in the end, was only part of the puzzle. Not because she—or the ancient Greeks—wanted to lie, or forgot, but because they didn’t know the whole truth. Myth might become reality, but history is not destiny.

This appeared in the April 2013 issue.