one night last July, I had a weird dream: in the kitchen of a house I didn’t recognize, I stood drinking beer with a bunch of bearded, grizzled-looking men. They spoke in a strange, jagged dialect, at once lilting and harsh, and the only English words I understood were “the Hag.” After a while, feeling alienated and ignored, I stabbed into the conversation: “The Hag this, the Hag that” (even in dreams, I’m not that clever), “what’s the big deal about the Hag? ” The room went quiet. Faces turned my way. “Never talk about the Hag that way,” one of the men whispered, with archetypal ghost story foreboding. “She’ll get you… in your sleep!”

I woke with an inexplicable tightness in my chest, but didn’t think much of the dream until later that afternoon when I met up with friends to watch the World Cup final. The following day, I was heading to St. John’s for the summer, to be joined a week later by my girlfriend, Stefanie. At halftime, my pals and I chatted about the trip. “Newfoundland, eh? ” said Matt, who’s spent some time on the Rock. “Are you worried at all about the Hag? ”

If you’ve ever had such an experience, you know the feeling: that sudden, jolting collision of waking and dream lives. The Hag (or “Old Hag”), Matt explained, is a Newfoundland superstition, a witch who comes in the night and sits on her sleeping victims’ chests. Though I was born in St. John’s, my family left when I was small; the place compels me, but I know little about it—part of the reason for the trip. At any rate, I had never, to my knowledge, heard of the Hag prior to my spookily prescient dream.

I’ve always loved ghost stories. I can plot my life through Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark (childhood) to Pet Sematary (adolescence) to Drag Me to Hell (last week). Here was a chance to live out my own Blair Witch Project, so my first night in St. John’s I went to bed hoping for an encounter. No such luck, that night or any of the next six before Stefanie arrived. Undeterred, I thought maybe I could conjure the Hag through lucid somnambulism or some sort of Newfie witchcraft. “Well, I won’t be sleeping in the same bed as you,” said Stefanie, unhelpfully, “if that’s what you’re up to.”

The next day, I headed to the Centre for Newfoundland Studies at Memorial University. (This is how the slasher pic Candyman starts out, too, with a graduate student researching Chicago urban legends.) After some confusion—“You want information on the Hague? ”—the amiable archivists produced a stack of books, magazines, and photocopied journal articles. From a 1952 edition of The Log: Official Organ of the Newfoundland Lumberman’s Association, I learned terminology (victims are “hag-rode”), and of alternate hag manifestations, such as the beclawed, almond-eyed “Chinamen” who slink into the bedrooms of snoozing fishermen and tickle their feet. Elsewhere, I heard of an outport family who found Grandpa under his bed, “wrestling with the devil.”

Next up was talking to an actual victim. Through friends in St. John’s, I met Carolyn Gill, a Fogo Islander who has been visited countless times by the Hag. She explained that while being hagged makes for entertaining stories, it’s a pretty horrible experience. In one particularly frightening episode, she reported, “A woman was crawling across the floor and up onto the bed. I could actually feel the mattress shifting under her weight, but I couldn’t move, I couldn’t do anything. She got on top of my chest and started strangling me. That’s when I got a good look at her face: it was me.”

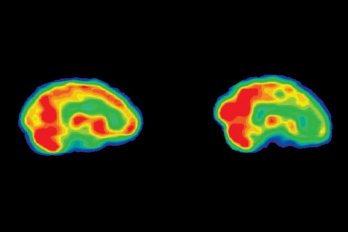

Gill stressed that a visit from the Old Hag’s isn’t the same as a nightmare: “It’s so vivid you’d swear you were awake.” Turns out you are, partly. Upon further reading, I learned that the Hag has a scientific basis. Sleep paralysis is an interruption of the REM cycle that renders one mentally awake while the body effectively remains asleep. It’s not all that uncommon, though the accompanying symptoms vary. As sufferers fully regain consciousness (a process that can take from a few seconds to several minutes), some sense a sinister presence in the room, which, for a select few, manifests as hallucinations. And this is where the Hag, literally, comes in.

Besides suggesting sleeping on my back, Carolyn didn’t have any ideas about how to make it happen on demand. So I called up Dr. Philip Hiscock, a professor and former archivist in Memorial’s department of folklore. He locates the Hag in the global succubus/incubus tradition of “witchy figures [and] devils having their way with sleeping mortals.” The general idea is not limited to Newfoundland, but it has been perpetuated there through the province’s rich folkloric tradition. In any culture, but especially among Newfoundlanders, storytelling serves as a method of building social cohesion and making sense of the world. “A lot of folklore is folk science,” Dr. Hiscock told me. “The Old Hag is a way of naming a phenomenon to exert power and control over it.”

But what about some tips? He laughed. “People ward off the Hag by placing their shoes facing the same way beside their beds—maybe you could reverse one of them? ” Eating cheese before sleep, he continued, is often linked with nightmares. What kind of cheese? “Well, before the ’70s most food in Newfoundland was processed, so maybe Kraft Singles would be your best bet.”

A few nights later, I watched The Crazies on DVD, followed his instructions, and turned in. “Remember,” I told Stefanie, “if it looks like I’m getting hagged, you can rescue me by chanting my name backwards.” She reached for the light switch and muttered, “Just don’t bring that thing to my side of the bed.”

A few hours later, a crocodile was hunting me through the halls of an abandoned mental hospital. He claimed to “just want to talk,” but I wasn’t hearing it; I had a basketball game to get to, and was already distraught enough about having a pair of pork chops for hands. I awoke flustered, clambering out of the dream in a sweaty, gulping rush… and felt the eerie presence of someone else in the room.

It turned out to be Stefanie, snoring gently. Though Dr. Hiscock had confirmed that the Hag could take multiple forms, I was pretty sure my sly crocodile and meaty mitts didn’t count. This thought was instantly followed by a sagging feeling. Considering how the men ignored me in that first, awkward (and, later, creepy) dream, maybe my subconscious hadn’t been telling me ghost stories, but expressing alienation from Newfoundland culture. Since I’m neither a native nor wholly an outsider, summoning the Hag was probably a vain attempt to forge a connection with the province of my birth.

I sat for a moment, watching the sun just starting to rise over Signal Hill. Beside me, Stefanie slept soundly. It was still very early—plenty of time left to join her in the land of dreams. But first I went downstairs, to eat another slice of cheese before going back to bed.

Trust No One

The jfk assassination leaves only fragments of truth

Eyewitness accounts are often fraught with error. Jean Hill, the “Lady in Red” in Abraham Zapruder’s film, was a well-known witness to jfk’s assassination, but she cast herself as a more central figure than the footage does. In her Warren Commission testimony, she claimed to have jumped toward the president’s limousine just before the shooting, shouting, “Hey, we want to take your picture!” The film attests that she did not move or speak during this time. (It suggests as well that the white dog she noticed in the backseat was a bouquet.) She also remembered chasing a man up the grassy knoll after the shots were fired, but photographs show her and a friend ducking. Visual records can be as spotty as memory, though. Some conspiracy theorists wonder whether Zapruder’s film was altered—or whether any record of the assassination can be trusted. It seems one person’s truth is as good as another’s.

—Mira Saraf

This appeared in the November 2010 issue.