Imet my husband fourteen years ago on a quietly spectacular blind date. He was funny and smart and gentlemanly, and there was a stillness about him that I found calming. By the end of the evening I was pretty much a goner. At some point that night, I remember saying that even if we didn’t go out again, I wanted him in my life in some way. I felt more deeply comfortable in his company than I ever had with anyone else, so freely alive and at home in my own skin that I put on the Rolling Stones and played air guitar while he looked on with amused fascination.

And so we did what people do when they collide in that way. We fell in love and moved in together and built a life and adopted each other’s families and bought a place and raised a kid and weathered crises and had adventures and dreamed our dreams. Every year on the anniversary of our first date, we agreed to renew our option for another year. I remember standing on a dais once and toasting my husband as my mate in the grandest sense of that word.

And then it all fell apart.

I have thought long and hard about what brought our marriage to the place where it now resides, and I can’t really say that I am much closer to unravelling the mystery. I have my theories and he has his. Who knows where the truth lies? Maybe our union was flawed from the start. Maybe we had expectations that were impossible to fulfill. Maybe we were missing some ingredient of self. Maybe our marriage just wore out, as marriages do. All I know is that we are two decent people who love each other and are living in a marriage that feels unfixable. And so, here I am, staring down the barrel of my own ambivalence, wondering whether to stay or go.

If I tough it out, there is some evidence suggesting I will be happier, in the long run, than if I leave. On the other hand, the damage is mounting, and maybe it would be best to cut my losses before more damage is done. Maybe it would be wiser to join the ranks of those leaving long-term marriages later in life, unwilling to squander whatever years they have left.

Since the Sixties, roughly twice as many of us are walking away from marriages and heading down that long, dusty highway in search of personal fulfillment’s Holy Grail. We’re not just fleeing from toddler marriages made in youthful haste, the so-called starter marriage, which doesn’t even count as a marriage any more—third is the new second, haven’t you heard? We’re not just fleeing quarter-century edifices toppled by the middle-aged crazies. Now we’re hobbling away on canes and walkers. Gays and lesbians may be beating down marriage’s double oak doors, but, increasingly, heterosexuals are leaving in droves. And living common-law is no insurance against the odds. Although more than half of us now live together before first marriages—often hoping to hedge our bets—those who do are likelier to divorce in the end; meanwhile, those of us who share quarters but swear off marriage altogether split up more often than if we had wed.

Not that those who stay married are necessarily models of marital bliss. According to a 1999 Rutgers University Study of the National Marriage Project, only 38 percent of Americans on their first marriage described themselves as “actually happy” in their situation. This is a rather whiplash-inducing statistic because it means that two-thirds—two thirds!—of first-married American couples are leading lives of quiet desperation, camping at the office, sobbing in the bathroom, playing Leonard Cohen on an endless loop.

What’s more, the ones who do leave never seem to learn. Although North American marriages combust approximately half the time, the compulsion to marry is deeply branded into our psyches: the American wedding business is a $70-billion (U.S.) juggernaut, glossy bridal mags entice from newsstands like high-priced hookers, and planning the perfect nuptials has become the entertainment du jour. We’ve got it bad, this soulmate for life thing, this sweet illusion that once we find The One, marriage will meet our every need.

What does it mean when so many long for lasting partnership, but so few know its secret?

For fifteen years, my parents had a brilliant marriage. It was traditional in that Fifties way, yet remarkably modern in sensibility. Even as a child, I sensed something profound and thrilling about it.

My father never made much money, but he was a man of grand gestures. I remember gazing wide-eyed when he put on Ella Fitzgerald and took my mother’s hand and danced her around the living room. The year he worked in New York, he sent her flowers every Friday. Often he came home bearing shiny packages with stylish outfits for her to wear. My mother, in turn, made a point of looking effortlessly beautiful, revered him as the man of the house, and made a loving home.

My parents’ marriage, in its heyday, remains for me the single most compelling model of a loving partnership that I know. It is a template—a precious jewel in my consciousness, which I take out to gaze at from time to time.

I have been thinking a lot about their marriage lately, mining it for clues. It worked in part, I think, because their roles were clearer and the avenues of exit not so freely available. But that is not the whole story. Whatever their private dissatisfactions, they seemed to view them as insignificant compared to their commitment to the grand experiment of their marriage and the task of raising their family. They parented with grace, but they did not make my sisters and me the obsessive focus of their lives. Children were expected to aspire to the grown-ups’ world, not the other way around, the way it seems today. Adult time was separate, sacrosanct. The boundaries were clearer.

This is important, I think, because, although they had a great capacity for playful enthusiasms, my parents were adult in a way that seems strangely foreign today. There was a gravitas about their marriage, which is not a word I would use to describe many marriages I see today. No doubt they had their grievances and resentments just like every other couple. But I never had the feeling (as I do so often today) that they viewed their marriage as diminishing of themselves. It seemed to both elevate them as individuals, and serve as an anchor mooring them to something larger than themselves.

Sometimes when the pressures of modern life grind us down, we tend to feel nostalgic for a time when marriage looked easier. But while marriages lasted longer once, they weren’t necessarily less gruelling. Indeed, we have always had a prurient interest in the miseries of marriage, and literature is full of horrendous accounts of unions gone sour. “Throughout most of literary history, marriage—particularly happy marriage—might as well be one of those empty spots on old maps inscribed with the words, ‘Here be monsters,’” writes Gary Kamiya on salon.com. “For every Kitty and Levin, the lovingly observed couple in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina who find grace as they work their way together through life, there are hundreds of Kareninas, Madame Bovarys and Casaubons…. Some of this void can be attributed to the uninspiring historic reality of marriage, which until fairly recently could be summed up as a business deal with bad sex….”

I once asked a friend who married young, built a life with the accoutrements of success, and has managed to stay happily married for thirty-odd years, to tell me why her marriage made it through. “Who knows why? ” she shrugged, in a way that suggested she’d asked herself the same question many times. “I married my drug dealer, for Christ’s sake.”

Indeed, one doesn’t have to look far to conclude that an enduring marriage is often a serendipitous accident. But even today, when we have spawned a culture of drive-by marriages and serial marriages, when the nuclear family has become an alternative lifestyle, when each new publishing season brings yet another avalanche of save-your-marriage manuals, the mythology of the storybook marriage remains an astonishingly potent force in our lives.

We can’t seem to let go of believing that marriage is the route to salvation. Marriage is a tenacious idea for many reasons, not only because the desire for intimate connection is profoundly human, or because, for many, marriage is a matter of consecration and faith, but because marriage is the glue that holds us together as a society. When marriage falters, the social fabric begins to unravel. This is not an argument against divorce, merely an acknowledgement that a huge and compelling body of social-science research points unequivocally to the conclusion that, in almost every way, divorce is bad for children and society.

And so, married couples, as well as governments and religious institutions, have a great deal invested in shoring up the myth of marriage—something that anyone who has lived through a divorce has experienced, often painfully. Whatever the state of their own marriages, perhaps because of it, couples find it deeply threatening when a marriage in their circle ends. It is like a cancer that must be contained before it metastasizes.

These two powerful pressures are at work all the time in our culture, subtly and not-so-subtly punishing and ostracizing those who remain unmarried by choice or destiny, and those who choose to leave an unfulfilling marriage. But what if the chief enemy of modern marriage isn’t the detritus of feminism or the killing stresses of modern life or our obsessive need for self-actualization—although each, no doubt, takes a toll. What if our problem is the pervasive mythology of marriage itself? Could it be, I wonder, that so many of us are failing at marriage because expecting to live happily with one person for the rest of our lives is an absurd idea?

This business of expectations interests me, because a marriage is always laced through with expectation, whether consciously expressed or not. And those expectations are implicit from the moment people marry, or enter into an arrangement that they consider a marriage, even though they may not have formalized that arrangement legally.

We have come to think of marriage as a private matter between two people in love, but marriage has never been a private matter. It is a public institution imbued with a motherlode of assumptions and expectations. Marriage and government have long been in bed together, entwined over property rights, welfare issues, taxation laws, and civil rights—a reality the same-sex marriage debate has highlighted, but not something most of us think about much.

One of the more fascinating books to enter the public discourse on this subject recently is Nancy Cott’s Public Vows: A History of Marriage and the Nation. Cott, a marriage historian and professor of American history at Harvard University, argues that in the U.S. the institution itself is a metaphor for citizenship, steeped as both traditions are in notions of vow-making and dewy-eyed idealism. When we marry, we grow up, get real, take our place in the nation-state.

Cott argues that legal authorities have always fashioned models of marriage finely calibrated to political ideals, and even though in Canada history took a different path, in both places cumulative associations to marriage models reverberate in the collective unconscious. In America, for instance, the founding fathers viewed monogamy as an alluring concept, because they saw neat parallels between the idea of monogamous marriage between two consenting adults and republican government by and for the people. Over the years, governments have used marriage as a handy tool with which to restrict or exclude certain groups (forbidding slaves and homosexuals to marry, for instance), and ideas about the definition of marriage have shifted according to the body politic. By the end of the last century, marriage came to be seen purely as a private matter between two consenting adults. Now, when we are less likely to marry than ever before, and more miserable and divorce-prone when we do, marriage remains very much a part of both the American and Canadian dreams, although our definition of marriage seems to have morphed into the seductive, albeit paradoxical, view that marriage is a cozy haven of emotional and economic security where avenues for “personal growth” continue to abound.

The result is that we are all carrying around this ideological freight, at once internalizing a profound belief in the moral rightness of marriage and being propelled into marriage by many symbolic cultural incentives and attractive economic ones, while remaining deeply skeptical of the marriages we observe and clearly conflicted about our own.

What is even more confounding is that just as the institution is in the process of imploding, it is being hailed as a panacea. We are in the midst of a huge marriage-is-good-for-you moment right now, so much so that to governments interested in staying in power, marriage is the new opiate of the masses. Marriage-boosters are either defending the institution against the latest alleged attacks on its integrity (“the gay assault”), or they are promoting its benefits as better for your health than a trip to Canyon Ranch (“married men live longer”). In an election-year initiative to promote marriage, President Bush and the Republicans floated a proposal to ask Congress for $1.5 billion ( U.S.) to help low-income couples develop interpersonal skills that sustain healthy marriages (which raises the question of what the middle class and filthy rich are to do about their plate-throwing).

What’s more, it is impossible to turn around these days without reading a study about how marriage is better for you than omega fatty acids. One of the more fear-mongering treatises on the transformative powers of the institution is Linda J. Waite and Maggie Gallagher’s The Case for Marriage, which makes anyone who isn’t married, or soon planning to wed, feel like a total loser. Waite, a professor of sociology at the University of Chicago, and Gallagher, director of the Marriage Program at the Institute of American Values, are like two industrious little marriage actuaries, reducing the subject to a cost-benefit analysis. Marry and you’ll boost your mutual funds! Marry and your kids will join the Ivy League! Marry and you’ll ward off heart disease! Resisting the impulse to marry is portrayed as such a dumb choice, one almost expects to see a picture of a blackened lung on the cover. But if marriage is such a hot deal, then why are so many people fleeing?

At what point my parents’ marriage began to unravel, I do not know, but, at seventy, my mother suffered a debilitating depression, moved into my sister’s home for a while to recover, and decided she wasn’t going back. She could have remarried, I suspect—she was a woman of many charms—but she always brushed off such suggestions laughingly, with a wave of her hand. “What do I need it for? ” she’d say.

My mother was philosophical about her marriage. She mourned its loss but did not see it as a personal failure, and, as far as I know, she never regretted it. Whatever her marital burdens, I never heard her speak ill of my father. She died last year and is buried beside him. All the ingredients were there for her marriage to have worked, but forces conspired against it. To her, its ending was her destiny, a part of her story.

My marriage is over now too, at least the marriage I have known. I have moved out, rented an apartment. Still, my husband and I remain deeply bound by intimacy, love, family, and history. It is still unclear whether our marriage will metamorphose. Certainly there’s no going back to what was. But the door remains open—to what, exactly, I do not know. We are making this up as we go along.

And yet, it is difficult to be hopeful. Sometimes the obstacles feel insurmountable and the differences too acute. We bled into each other. It became difficult to know where he ended and I began. And the odds are not good. Divorce is a strong theme in my family. My daughter still talks about the family tree she once compiled for a Sunday school project where the list of broken marriages was so long, one of the kids asked, “Even your grandma’s divorced? ” Her parents and stepparents, she likes to remind me, have racked up ten marriages among them. This is the third time around for both my husband and me, although, this time, he and I never actually married. And yet, in spite of its darkest moments and our unwedded state, I can say, unequivocally, that this is the best marriage I have ever had. Certainly it feels like the truest.

My daughter is twenty-four. She is the cool realist about marriage in the family. It embarrasses me to admit that I’m the one who still cries watching A Wedding Story. She just rolls her eyes. “I’m never getting married,” she says. “Marriage doesn’t work.” Still, I think this is just a defence. I think she would like to feel that marriage is possible, but she can’t risk believing in what seems to her such a doomed enterprise. I blame myself for her cynicism, of course. How is she supposed to believe, as I do, that aspiring to intimate partnership is a worthy goal, when all around her marriages are collapsing?

I want to give her some hope, but I’m not sure what to say, and platitudes are pointless. My husband tells her that just because marriage doesn’t always last doesn’t mean it isn’t deeply satisfying to experience a good marriage for a time. I tell her I think there is something of great value in marriage, some opportunity to achieve a certain wisdom and generosity and patience that only a marriage can bestow. I want to be married, I tell her. I’m just not sure how.

How many happily married couples do you know? I can’t speak for other communities or social groups, but certainly in the circles in which I travel—an urban, North American middle class whose formative years were profoundly shaped by the Sixties—most people can count on two fingers the number of poster marriages they’ve observed. And even then, all you can ever do is press your nose up against the glass and wonder, “How are they doing? ” I asked a friend about a couple we both knew whose marriage was faltering. His own marriage, at least to my eye, has always seemed solid and true. “How well are any of us doing? ” he shrugged. When another friend announced that she was moving in with the man in her life, her phone started ringing with calls from married female friends anxious to know what she was doing with her apartment. For a while, it looked as if there might be a bidding war. “I’m thinking of turning it into a shelter for married women,” she joked. And yet, as a culture, we tend to pity those who prefer to take their chances on the open seas rather than go down with the ship.

And why is it that the moment you’re through the gates, married people have this compulsion to fix you up? I’m not talking about the contentedly married, who, in their sweet and generous naïveté, simply can’t imagine why anyone would be happier flying solo; I’m talking about the ones who find your action deeply unnerving because they perceive in it an implicit judgment on their own inaction, and hasten to restore order.

I know of only a handful of marriages I would want for my own. I know what a good marriage feels like, and once you’ve known the feeling, it’s hard to settle for less. But most of the marriages I observe fall short of the mythologized version. I see serviceable marriages based on routine, dysfunctional marriages supported by a web of lies, marriages sustained by social ritual, marriages whose bones are brittle with calcified resentments, marriages where the contempt is so palpable it oozes between the cracks like primordial slime, marriages that went on life-support years ago: dead couples walking.

And yet, when incontrovertible evidence suggests that most of us are, at best, ambivalent about marriage, when only a lucky few seem to have mastered the trick of contented coupledom, when the institution itself seems to be flailing about in the grip of social Darwinism, when it is becoming increasingly evident that marriage itself may be the culprit here, or at least our current ideas about marriage, there is still a terrible sense of failure when a marriage ends.

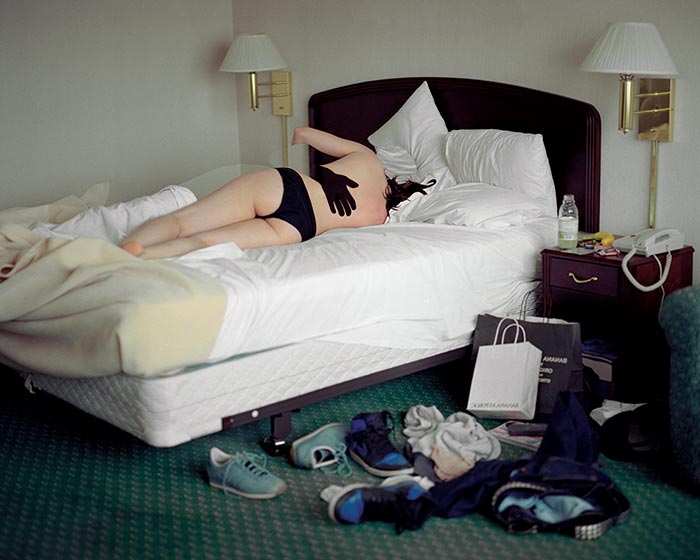

Somebody ought to sue marriage for false advertising. It’s supposed to be this honeymoon hotel where you check in with your soulmate for life and you crack open the bubbly of your hopes and toast your good fortune and go to sleep on the Frette linens of emotional intimacy and elegant communication and mutual fulfillment and rewarding sex. You know in some vague way, standing at the threshold, that it’s not all going to be a bed of roses—there’ll be leaks in the ceiling and the remote won’t work and you’ll have to call housekeeping from time to time, but mostly, when the door snaps shut behind you, you’ll loosen your tie, kick off your heels, pillage the minibar and breathe a sigh of relief that you’re home sweet home. Over time you’ll be able to afford a suite, maybe even separate bedrooms—by then the fever will have broken—but you’ll have entered the Oz of Enduring Love, which has its own rewards. And when the going gets tough, there’ll be those endless reserves of trust and affection and respect to see you through. Or so marriage’s brand marketers would have us believe.

What you will not feel is doubt. Or contempt. Or boredom. Or disgust. Or exhaustion. Or despair. Or desperation. Or the desire to flee. Or bouts of such hatred for your spouse that you start realizing the true miracle of modern marriage is not that half survive, but that more don’t end in murder.

It strikes me as nothing short of astonishing how two people can travel the distance between adoring affection and lethal rage and back again. I know of a couple whose marriage endured Shakespearean trials. For a time she hated him so much that she would lie beside him in bed at night thinking “Die! Die!” Now they take cooking courses together. How does this happen? How does one partnership survive while another crumbles under the weight of too many “fuck you”s?

Let’s talk about ambivalence for a moment, because ambivalence, it seems, is the quicksand on which modern marriage is built. A happily married man of my acquaintance says that he loves his wife and sometimes he hates her, but that he loves her more than he hates her, which strikes me as a pretty decent definition of the precarious balance on which most marriages teeter. His wife attributes their marital success to the fact that they never fell out of love at the same time. Joan Didion, whose marriage to the late John Gregory Dunne was, by all accounts, a splendid partnership, once said that she and Dunne wished their epitaph to read “We had fun,” which has always struck me as the single most eloquent testimonial to a marriage that I have ever heard. And yet Didion also famously wrote that marriage was the “classic betrayal.”

Laura Kipnis whose bracing polemic Against Love should be required reading for anyone contemplating the crap-shoot that is modern marriage, says it’s no mystery why the current declining couple form is mired in ambivalence:

“On the one hand, the yearning for intimacy, on the other, the desire for autonomy; on the one hand, the comfort and security of routine, on the other hand, its soul-deadening predictability; on the one side, the pleasure of being deeply known (and deeply knowing another person), on the other, the strait-jacketed roles that such familiarity predicates—the shtick of couple interactions; the repetition of the arguments; the boredom and rigidities which aren’t about to be transcended in this or any other lifetime, and which harden into those all-too-familiar couple routines: the Stop Trying To Change Me routine and the Stop Blaming Me For Your Unhappiness routine. (Novelist Vince Passaro: ‘It is difficult to imagine a modern middle-class marriage not syncopated by rage.’) Not to mention the regression, because, after all, you’ve chosen your parent (or their opposite), or worse, you’ve become your parent, tormenting (or withdrawing from) the mate as the same-or-opposite-sex parent once did, replaying scenes you were once subjected to yourself as a helpless child—or some other variety of family repetition that will keep those therapists guessing for years. Given everything, a success rate of 50 percent seems about right (assuming success means longevity).”

The truth is that if you put modern marriage under a microscope, its emotional climate will start to look a whole lot more like Tony and Carmela Soprano’s than Ward and June Cleaver’s. All marriages hinge on the dialectic between interest and boredom, passion and contempt, adoration and hatred. All marriages have secrets. All marriages are deals struck. All marriages, at some point, are exercises in masochism and futility. But if that’s the case, why is nobody talking?

To say that there is a conspiratorial silence about marriage may seem like a strange assertion in a confessional culture where so much is exposed you begin to wish for a little dignified restraint. But for all the obsessional taking of marriage’s pulse, for all the sordid, maudlin bloodlettings on talk TV, nobody really talks about what a marriage looks like at the molecular level. It is the last taboo. People would sooner talk about their colonoscopies.

“Yesterday I left the hotel and drove into the country, to a tiny town at the edge of California,” writes relationships author and humourist Cynthia Heimel: “A hotel was the marriage counselor’s idea. ‘When it gets like that, pick up your purse, go to a hotel,’ she said…. “How do marriage counselors sleep at night, knowing all they know about marriage and not screaming it to the world? They should stand on their rooftops in their pajamas with megaphones, shouting, ‘Citizens! Heed my words! Never marry! Marriage is bad! Marriage is a bloodbath!’

“But no, everybody keeps mum. No one tells you about the sniping in the kitchen, the words like grenades flung across the bed, the radioactive silences in the rose garden. It’s a big state secret that the merest ghost of a grimace of disapproval can cause cold-blood rage.”

For the truth, at least competing versions of it, we usually have to wait for the split: he was gay, she had an affair, they didn’t have sex for ten years. And even then, we’re only privy to the sound bites. We’re not allowed to see the storyboard, to watch the marriage unfolding scene by scene.

So here we all are, colluding in this massive denial, propping up this myth that marriage meets our every need, which brings me to the subject of lousy sex. We are living in an age when there appears to be an inverse ratio between the amount of sex you can watch other people having, and the amount you can actually have with the person who shares your bed.

We have now officially entered the era of the sexless marriage, another cruel irony of our time because it seems to me that one of the main reasons for putting up with all the shit you have to put up with in marriage is because you can have sex on a fairly regular basis. And the best part about this marital perk is that it’s relatively low-maintenance sex: it doesn’t involve getting dressed up and going out and pretending you find someone’s jokes funny.

And yet, if the sardonic comments I frequently hear on this subject are any indication, it’s almost become hip to have a monastic marital life these days. To qualify for membership in the sexless marriage club, you cannot be doing it more than ten times a year. If you believe the stats—always a mug’s game because people tend to lie their faces off in sex polls—this goal has allegedly been achieved by 15 to 20 percent of American couples. Personally, I think they’re lowballing. So does the author of The Sex-Starved Marriage, Michele Weiner Davis, who considers the problem “grossly under-reported.”

Then again, you can believe a far more reliable source—Dr. Phil, who says on his Web site that we’re in the midst of an epidemic. Or the women’s magazines, which are jam-packed with perk-up-your-love-life remedies. Or the riddled-with-contempt accounts of the sexually flatlining, two-career marriage with kids, like Allison Pearson’s I Don’t Know How She Does It. If, as psychologist John Gottman, director of the University of Washington’s Family Research Lab observes, the sudden decline of marital sex is a bellwether, like those one-eyed frogs that presage environmental disaster, then apocalypse is nigh.

It is a dark irony, as Caitlin Flanagan pointed out in “The Wifely Duty” a provocative piece in The Atlantic last year, that the hyper-sexualized, libertine, post-sexual-revolution generation are a rather sex-starved group, and indeed may be the first generation in history that needs advice on how to, as Flanagan puts it, “get the canoe out in the water.” In any event, it seems clear that “those repressed and much pitied 1950s wives—their sexless college years! their boorish husbands, who couldn’t locate the clitoris with a flashlight and a copy of Gray’s Anatomy!—were apparently getting a lot more action than many of today’s most liberated and sexually experienced married women…. The characters one encounters in Cheever and Updike, with their cocktails and cigarettes and affairs, seem at once infinitely more dissolute and more adult than most of the young parents I know. Nowadays, American parents of a certain social class seem squeaky clean, high-achieving, flush with cash, relatively exhausted, obsessed with their children, and somehow—how to pinpoint this?—undersexed.”

Forget the myth. All it does is make us feel as if we’re failing. I want models that inspire me, models I can learn from. I am fascinated by the Clinton marriage because it has always struck me as a Rorschach of a modern marriage in all its glorious and terrible ambiguities. In its clash of Titans and shifting power relationships and dual-career pressures and co-parenting dilemmas and mid-life affairs and marriage sabbaticals and monumental achievements and annihilating furies and negotiations, betrayals and accommodations, it seems to contain, in grand scope, all the jostling, flawed elements present in most marriages I know. It is Modern Marriage writ large.

But it’s also a cipher for all the projections about marriage in our culture. In the aftermath of the Lewinsky scandal, the clichés came out full force. What was this marriage, anyway? A Faustian bargain? A cynical match born of political expediency? A perverse co-dependency? It was not until the philandering husband was ritually humiliated and the feminist virago morphed into the wounded-but-stoically-enduring wife, that order was restored. Not surprisingly, Hillary’s currency with the American public soared to its highest levels during her husband’s impeachment hearings. Americans liked her better with a little more Tammy Wynette in the mix.

In his biography, My Life, Clinton wrote that after being married for nearly thirty years and observing his friends’ experience with separations, reconciliations, and divorces, he had learned that marriage, “with all its magic and misery, its contentments and disappointments, remains a mystery, not easy for those in it to understand and largely inaccessible to outsiders.”

Whatever the truth at the heart of the Clinton marriage—indeed, whether or not it ultimately endures—it has always puzzled me how anyone could view it as anything but the real deal.

I read somewhere once that there is nothing sexier than a married man who has not given up on life, and I have often wondered what it must be like for Hillary to be married to a man whose sexual magnetism is legendary, when her power resides elsewhere. Still, whatever your views on fidelity, I think it is impossible not to sense the presence of some aliveness, some kinetic energy in the marriage. And, contrary to the many harsh judgments I read about her, I have never viewed Hillary Rodham Clinton as a throwback to an era when women simply stood by their men, no matter how humiliating their transgressions. To me she is uncompromisingly herself, a truly modern woman who showed strength, maturity, and grace under pressure and who radiates a complex yet clear-eyed understanding of what is ultimately important in a marriage and what is not. Whatever its limitations, it seems apparent that both of the individuals who inhabit this marriage find something of great depth and renewal there.

This marriage, unlike so many I observe, does not have the whiff of complacency about it. Like all interesting marriages, it evolves. To my eye it looks like a jazz improvisation, an organic experiment with form that constantly surprises and steadfastly refuses to follow a set score, reminding us that this partnership of equals is a complicated matter requiring complicated choices and solutions, that the one-dimensional scripts we have devised for marriage no longer apply, that not only is it possible to define marriage more fluidly than we have in the past, but necessary, and that monogamy may not be the fundamental basis of an enduring marriage that we once thought it was.

Experts will tell you that every marriage, sooner or later, experiences a crisis of disappointment. Couples can choose to negotiate this Waterloo in many ways, but one of the less-talked about is to acknowledge that it is normal to feel the need to live separately at times in a marriage, and choosing to do so doesn’t necessarily have to mean that the marriage has malfunctioned. I have often wondered why we don’t just acknowledge this reality from the start, and view periodic separation as a normal stage of a healthy marriage, like letting a field lie fallow to regenerate. Marriage, after all, is a commitment to share one’s life intimately with another person, and that commitment can take many forms. Who’s to say that couples who live physically together but emotionally apart are married, while couples who live separately, but remain intimately connected, are not?

And so, here I am, on marriage’s new frontiers, without a map, doing my best to improvise. I don’t have any answers. Marriage is as mysterious to me now as it ever was. All I know is that in its most eloquent expression, it is a lunatic idea worth fighting for.