THE INSTANT Grant Bristow answered the telephone on Friday morning, August 12, 1994, the new, sedate life he had built in a bland Toronto suburb for himself, his wife, and son began to unravel. For six years, Bristow had inhabited the perilous universe of white supremacists as a mole for the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (csis).

Months earlier, Bristow had gladly walked away from racists and espionage, his cover still safely intact. Now the reassuring routine of home, work, and soccer practices was about to be replaced by a whiff of panic. The caller was Bill Dunphy, a Toronto Sun reporter who had unearthed Bristow’s unlisted home telephone number.

“Grant, we need to meet,” Dunphy said.

“What’s up? ” Bristow said warily.

“It’s important,” was all Dunphy would say. Bristow agreed to a meeting that afternoon in the parking lot of a nearby restaurant.

Dunphy was waiting when Bristow arrived. He hopped into the front seat of Bristow’s car and got right to the point. “Grant,” he said, “I’m going to press with a story that says you were a csis mole inside the racist right wing. This is your opportunity to tell your side of the story.”

“I’ve got nothing to say,” Bristow replied, trying to mask his shock behind a steady gaze. When Dunphy made it clear that the story would run in less than forty-eight hours whether he talked or not, Bristow made an appeal. “You’re going to press with something that will anger some people,” he said. “I’ve got a family to protect. At least give me a little time to get my kid to safety.”

Dunphy refused.

“Don’t be an asshole,” Bristow snapped before leaving. After racing home from the unsettling rendezvous, Bristow calmly told his wife about the planned exposé, then called his former csis handler to cobble together an escape plan. The family quickly packed, crammed their suitcases into their Chevrolet Cavalier, and headed for a nearby hotel, where Bristow checked in using a prearranged alias.

At the hotel, his ex-handler and another intelligence officer greeted Bristow with handshakes and strained smiles. Bristow’s sickening sense of unease began to subside when they assured him that, whatever the story’s spin, the covert operation had been a resounding success and that he had little to fear from the impending publicity. “At this rate,” Bristow assured himself, “I was beginning to think that I might be a national hero by Monday.”

As Bristow waited for the article to appear, his mood oscillated from mild anticipation to an almost paralyzing anxiety. But when the paper arrived early Sunday morning, his worst fears were realized. The tabloid’s headline blared: “Spy Unmasked: csis informant ‘founding father’ of white racist group.” Quoting members of Canada’s racist right, Dunphy drew a damning portrait of Bristow as a government-paid villain, a key architect of the campaign of racial hatred run by the Heritage Front, the country’s largest, most notorious neo-Nazi group. Bristow stared at the headline, slowly shaking his head in a mixture of anger and bewilderment. “It was the worst day of my life,” Bristow said later.

Dunphy’s most searing and potentially damaging allegation was that, with the blessing and encouragement of his csis handlers and using Canadian taxpayers’ money, Grant Bristow had not only helped create the racist “monster” whom he was supposed to merely monitor, but had “goad[ed] it into a dangerous rage.” A former Heritage Front member told Dunphy, “Grant brings the wood, he brings the kindling, he brings the match and says, ‘Light it.’”

A day after the explosive story broke, the spy agency’s civilian watchdog, the Security Intelligence Review Committee (sirc), launched a probe into what they called “The Heritage Front Affair.” Four months later, sirc issued a verdict based on “source reports, csis files and interviews”: Bristow and his handlers had done the right thing for the right reasons.

sirc found that while Bristow (never identified by name in the report) was part of the Heritage Front’s “inner leadership,” he played only a small role in its genesis and growth.

The review committee rebuked Bristow for having employed tactics that “tested the limits . . . of acceptable and appropriate behaviour,” but ultimately found that Canadians owed him a debt of gratitude for “doing valuable work helping to protect Canadian society from a cancer growing within.”

Opposition parties and civil libertarians dismissed the report as a “whitewash.” But the media hysteria that had enveloped Bristow quickly evaporated as much of the press accepted sirc’s findings and considered the case closed.

Through it all, Bristow never uttered a word publicly about his unprecedented journey into the netherworld of racial hatred and violence. His long silence has only deepened the mystery and the ambiguity that surrounded his clandestine work for csis. To his foes, he is a Judas who betrayed loyal friends. To others, he remains an unrepentant agent-provocateur on the public payroll. Still others consider him a hero who risked his life for his beliefs, and is now living with the consequences—a dissolved marriage, an uncertain future, and an occasional brush with fear.

Last summer, almost nine years to the day after that fateful phone call from the Sun reporter, Grant Bristow finally decided to tell his side of the story. Sitting in a small, drab Edmonton motel room with its heavy drapes allowing only a sliver of sunlight to seep in, this tall, burly man with a middle-age paunch and receding hairline took a calming drag on a cigarette and cast his mind back to the frenzied days when his work and life were unexpectedly thrust into the unwelcome spotlight. The guile, the charm, the self-confidence that routinely tips into arrogance—all the qualities that made him an effective mole—were on display.

“I was fucking good,” Bristow announced, with an unabashed cockiness. Indeed, he was. Bristow was perhaps the only mole to have insinuated himself so deeply into the international neo-Nazi movement’s inner orbit. He was talking now, he said, because he wanted to set the record straight. Despite sirc’s belated “vindication,” in the years following his “outing,” the image of him as a government-paid hate-merchant had seemingly become fixed in stone. “Now is the time,” he said defiantly, “that I can say,’Not guilty.’”

Grant Bristow never intended to become a spy. Born in Winnipeg in February, 1958, Bristow was the youngest of three children—two boys and a girl. His upbringing was comfortably middle class: a large home, boy scouts, good schools, and languid summers spent at the cottage. Bristow’s father was a civilian employee at the Department of National Defence. His mother, a maverick, became a banker in the 1960s, a time when most women on Bay Street worked behind a typewriter. At the age of eleven, Bristow’s almost idyllic world was shattered when his parents divorced after seventeen years of marriage. In search of a new beginning, his mother, Janet, remarried and, with her two sons in tow (the daughter remained with her father in Winnipeg), moved to Halifax, then Toronto. Grant threw himself into school and Junior Achievement, a program that nurtured entrepreneurial spirit. “The prospect of being a dealmaker appealed to me,” Bristow says.

In the early 1980s, Bristow graduated from a Toronto community college with a business diploma, and became a private investigator—at first blush, a surprising career choice for a product of middle-class suburbia. But the job fitted Bristow’s temperament. A natural chameleon, he shifted effortlessly from one persona to another, cultivating friendships with ease. Yet behind the engaging smile lay a steely-minded loner who guarded secrets well.

Over the next few years, Bristow polished his skills with several investigation firms in Toronto, conducting surveillance, background checks, probes into insurance fraud and vandalism, and providing hotel security. He graduated to undercover operations that required him to assume a variety of identities and win people’s faith and confidence while erasing any evidence of his past. The work built on his innate ability to observe, anticipate, and mimic the actions of others. With time, Bristow became an accomplished actor, and that, combined with his appetite for a healthy paycheque and his love of the work, made him an ideal undercover agent.

Bristow’s taste for intrigue and subterfuge seemed at odds with another, more charitable, aspect of his nature. His mother, Bristow says, imbued him with a devotion to civil rights. The stirring speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr., and John F. Kennedy, and the courage of Rosa Parks, the mother of the civil-rights movement in the United States, cemented Janet Bristow’s abiding belief in the equality of all races, says Bristow. Like her, he became determined to make the world “a less hateful place.”

Another early and potent influence was a family friend, Maurice Klagsbrun, a European Jew who, as a child, had seen most of his family destroyed by the Holocaust. Sheltered by Belgian nuns, Maurice survived, and was later taken in as a foster child by a Jewish family whose name he adopted. Klagsbrun’s story left an indelible mark on Bristow.

Bristow’s long, covert affair with csis began in early 1986 when a South African diplomat called from Ottawa and offered the budding private eye a lucrative contract to provide security for the then-rogue state’s diplomatic missions in Canada. (At the time, the government of President P.W. Botha was still brutally suppressing the country’s majority black population, and anti-apartheid demonstrators around the globe routinely vented their revulsion and anger in front of South Africa’s diplomatic posts abroad.) Bristow expressed an interest and met the envoy—an immaculately dressed man with a beaming smile—for an expensive lunch at the Sutton Place hotel in downtown Toronto. Between courses, the diplomat discreetly told Bristow that he needed someone to build up dossiers on Canadian “agitators.” Bristow realized that he was being asked to spy on Canadians who were legitimately expressing their opposition to apartheid. He was willing to provide security for the South Africans, he says, but he was not prepared to cross the line into espionage for a foreign government. He feigned interest, however, and then, on the advice of a friend, arranged to meet a csis officer to report the South African’s overture. Not surprisingly, the officer wanted to reel in the foreign diplomat-cum-spy, so Bristow agreed to take on the assignment and report back to csis.

Bristow’s first foray into the duplicitous world of espionage was an unqualified success. On August 20, 1986, Ottawa expelled one South African diplomat from the country and barred another from returning to Canada. In the nomenclature of spies, Bristow had become an “asset.”

Early the following year, Bristow had a chance meeting with Max French, described as a “right-wing nut bar” by the friend who introduced them. At the time, Bristow knew little, if anything, about right-wing extremism in Canada. Nevertheless, he reported his encounter to csis and was encouraged to befriend French and take a peek into the racist right. Bristow agreed, but cautioned his new csis handler that he had just joined Kuehne and Nagel, one of the world’s largest logistics and transportation firms, as an in-house investigator.

To help ease Bristow’s entry into the white supremacists’ milieu, csis gave him a cursory sketch of the movement’s principal players, along with a copy of The Turner Diaries; written in 1978 by William Pierce, a former physics professor and neo-Nazi, it is a fantasy novel that serves as a manifesto for many white supremacists. (The book centres on a fictional race war that results in the overthrow of the US government and the systematic killing of Jews and non-whites, followed by the establishment of an “Aryan” world order.)

Bristow’s efforts to befriend French failed, but a few months later he managed to penetrate the extreme right when a fellow private investigator introduced him to a zealous anti-Communist and a Jew who had apparently repudiated his faith. He invited Bristow to a meeting of the Nationalist Party of Canada, held at the modest Toronto home of its leader, Don Andrews. Andrews had emigrated from Yugoslavia in 1952; he later used money he made as a landlord to bankroll a steady stream of racist propaganda, which led to his conviction in 1985 for spreading hatred. By then, Andrews was a fixture in the white supremacist movement in Canada, holding court on Saturday mornings when his followers, dubbed “Androids,” would gather at his home to listen to his paranoid invective.

In the fall of 1988, Bristow stepped into what was then the heart of Canada’s racist right. And so began csis’s Operation Governor. According to Bristow, when the operation was launched, there was no master plan, no timetable, and no list of defined targets. In fact, the probe was little more than a fact-finding mission, with Bristow poking at the margins of the radical right. Although he regularly took instructions from his handlers, Bristow enjoyed a large measure of autonomy. Operation Governor’s success or failure would depend entirely on him.

Bristow had arrived at an opportune time. The movement was aching for new members and he stood out, intellectually and financially, from most Nationalist Party members, many of whom were high-school dropouts, unemployed, or on welfare. Andrews welcomed him unreservedly and, in return, Bristow stroked Andrews’ large ego and mimicked the Nationalist Party leader’s behaviour and rhetoric. In intelligence lingo, Bristow was “mirroring” his target in order to establish a psychological kinship with him.

Bristow’s presence inside the racist right proved to be far more fruitful than the conventional methods of physical and electronic surveillance. “Wiretaps can’t describe facial expressions, body language,” Bristow says. “They can’t distinguish motives. They can’t provide context. They can’t separate truth from bullshit, and who is a player and who is not.”

Don Andrews was considered a player, but Canada’s racist right was given renewed life when the white supremacist Wolfgang Walter Droege, in April, 1989, was deported back to Canada after serving a four-year prison sentence in the US for cocaine trafficking and the possession of an illegal weapon. Droege was eager to translate the Nationalist Party’s virulent rhetoric into action, and his racist credentials were as impeccable as they were cockeyed. As a child in Bavaria, Germany, Droege had been a devout admirer of Hitler, and yearned for a white homeland. Later, he was inspired by David Duke, the tall, blond, blue-eyed Grand Imperial Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, exhorting the faithful to unite and save the white race from extinction. Droege had helped launch the Canadian Knights of the Ku Klux Klan and later conspired, unsuccessfully, to invade the tiny Caribbean island of Dominica, which he had planned to use as a power base from which to plot and underwrite white supremacist activity throughout the world.

Andrews organized a “welcome home” party for Droege, and invited Bristow to attend. It was a boisterous affair, where “plainclothes neo-Nazis,” wearing shirts, jackets, and ties mingled with tattooed skinheads and their pale, anemic-looking girlfriends. Droege gravitated to Bristow. Like Andrews, he was taken with Bristow’s apparent street smarts, security experience, and financial independence. Bristow confessed to finding the portly, balding Droege almost charming.

Droege’s presence transformed Operation Governor. According to Bristow, Droege—in contrast to Andrews and his sordid band of hangers-on—was “the real meal deal.” In the weeks following their introduction, Bristow shifted his focus from Andrews to Droege. Predictably, Droege began to confide in Bristow, describing the influence that his maternal grandfather’s allegiance to Hitler and National Socialism had had on his own political “maturation.” Droege also began betraying other, more incriminating secrets of his past. He admitted, Bristow says, to trafficking drugs to fund his racist activity. Droege also acknowledged that he was a “second-tier” member of The Order, a US-based white supremacist terror group involved in bank robberies, counterfeiting, and even murder. He claimed he had once travelled to Alabama on a mission for The Order that involved an aborted plan to assassinate Morris Dees, a prominent civil-rights lawyer.

Bristow was now living a schizophrenic existence. By day, he worked as an investigator. On weekends and evenings, he nurtured his ties to the racist right, assiduously keeping to his cover story that he was an orphan who was devoted to the supremacy of the white race. What ultimately allowed him to do what most would consider unfathomable—live among racists—was his commitment to the work. “I was keeping watch over violent hate groups,” he said.

“It was the right thing to do.”

After being made security chief for the Nationalist Party, Bristow screened a steady stream of new recruits. He drew up a form on which new members provided their names, occupations, home addresses, and telephone numbers. Aspirants also had to declare that they were racists and pledge “to establish . . . a constitutional racist homeland . . . under the leadership of Don Andrews.” Bristow passed all the information on to csis, providing the spy agency with what amounted to the Nationalist Party’s master membership list. The forms also reflected the changing face of neo-Naziism in Canada in the late 1980s: Bristow says that many of the new recruits were young, either attending university or working. Most were social outcasts searching for a place to share their skewed values and beliefs.

By July, 1989, Wolfgang Droege was becoming disenchanted with Andrews’ Saturday-morning hate-sessions and began toying with the notion of establishing a splinter organization that would more aggressively promote the interests of whites. He was spurred on by a bizarre interlude that cemented his relationship with Bristow, even as it nearly drove Bristow to abandon his undercover role.

That summer, Andrews received an invitation from Colonel Muammar Qaddafi to attend, all expenses paid, the twentieth-anniversary celebration of the Libyan revolution in Tripoli. An international pariah, Qaddafi was seeking to muster support for his regime among extremists on both the left and the right who, despite their profound ideological differences, he believed, shared a common enemy: Zionism. Andrews and Droege viewed the Libyans as possible benefactors, but when the Nationalist Party leader begged off the trip, citing his pending court case, Droege agreed to go, insisting that Bristow join him. In all, seventeen Nationalist Party members made the ten-day trip to Tripoli via Rome in late August, 1989.

The problems began when the group was detained at the Rome airport by Italian intelligence officers, who attempted to dissuade the Canadian neo-Nazis from travelling on to Libya. Fearing that his cover might be blown, Bristow considered returning to Toronto. But they were eventually released, and flew on to Malta, where the group boarded an aging ocean-liner laden with right- and left-wing extremists for the dreary seventeen-hour voyage to Tripoli. Once in Libya, Droege made several futile attempts to strike up a relationship with a Libyan intelligence officer to make a pitch for money, but in the end they were offered a paltry $1,000(US) as a parting gift.

On the return flight, the airliner made a stopover in Chicago, where Droege, who had been barred from entering the United States, was promptly arrested by US Immigration officials. Bristow was also detained and strip-searched. After several hours of questioning, he was released. Relieved but shaken, he alerted Canadian consular officials to Droege’s arrest, found a lawyer to represent him, then headed back to Toronto. Forty-eight hours later, Droege was deported to Canada.

Bristow was now convinced that his troubles in Rome and his detention by American authorities in Chicago meant that csis was treating him as an expendable pawn. He confronted his handler at a safe house in Toronto. “What the fuck happened? ” Bristow shouted. “There’s no operation. You and I are finished.”

The intelligence officer explained that while csis was aware of what had happened in Rome and Chicago, it couldn’t intervene without running the risk of compromising his cover. Another, more senior csis officer assured Bristow that he would not be “exposed” again. As his anger ebbed, Bristow agreed to continue Operation Governor, but demanded that the memorandum of understanding he had signed with the spy service be amended to include provisions that he be warned of any future takedowns. csis agreed.

The trip had other consequences. The shared adversity drew Droege even closer to Bristow. Bristow says they became “inseparable.” Convinced that Andrews had engineered his arrest in Chicago, Droege now moved swiftly to set up the new white supremacist organization that had been percolating in his mind since his release from prison. It would be a well-organized, media-savvy group that would bring together, under one ideological roof, dedicated racists from across Canada and from sister organizations in the United States. Droege instructed a follower to register the name—The Heritage Front—on October 2, 1989.

Droege’s mentor, David Duke, had understood that images of cross burnings and hooded KKK members did little to broaden the movement’s political appeal among middle-class, white voters. Droege began drawing up a pseudo-political manifesto that parroted Duke’s sanitized, anti-immigrant, “white and proud” rhetoric.

Bristow readily admits that in all this, he acted as Droege’s trusted lieutenant, someone the Heritage Front leader could turn to for advice and guidance. He remains unapologetic about assuming the role. It had to be done, Bristow insists, to maintain his cover and to enable him to continue feeding intelligence to csis about Droege’s plans to revitalize the racist right in Canada. “Make no mistake,” Bristow says pointedly, “Droege was captain of the ship.”

In his own defence, Bristow claims to have convinced Droege that many of his ideas for the movement were either unworkable or counter-productive. But Droege’s pursuit of the Libyans confirmed to Bristow just how far the racist right was prepared to go to achieve its lunatic goals.

In September 1990, Sean Maguire—a tall, blond, blue-eyed member of the US paramilitary white supremacist group, Aryan Nations—contacted Bristow, who, as the Heritage Front’s security chief, was now responsible for maintaining ties with American brothers-in-arms. Maguire told Bristow that a colleague, Craig Zanotti, had hatched a plan to launch an ecological terror attack. The aim was to disrupt, or even paralyze, the North American food chain by infecting crops with a new, hard-to-combat virus. Because US law enforcement agencies were watching Aryan Nations, said Maguire, the group had decided to give the terror plot to their Canadian partners-in-hate.

Days later, Maguire and Zanotti met with Droege and Bristow at a dingy bar in Windsor, Ontario. Bristow flipped through a thirty-six-page typescript of the plan, searching for the key points, while a jittery Zanotti tried to explain the science behind it. The university student then suggested that Bristow and Droege sell his plan to the Iraqi government.

Upon his return to Toronto, Bristow immediately met with his csis handler and gave him a copy of the report. Droege, meanwhile, was contacting a former high-ranking Canadian diplomat with longstanding ties to the racist right, to make arrangements to sell the eco-terror plot to Libyan envoys in New York. Eventually, csis determined that Zanotti’s plan was scientifically unsound and Bristow persuaded Droege to drop the idea, telling him it wasn’t worth another risky trip to the US

What unnerved Bristow, however, was the willingness, even eagerness, of Maguire and Droege to carry out the plan. “Their excitement was unsettling,” Bristow says.

The episode confirmed the kind of real-time intelligence that Operation Governor was generating. It was also tangible evidence of how convincing Bristow’s performance as a white supremacist had become.

If Sean Maguire was, in a sense, the physical incarnation of the racist right, then Canadian Ernst Zundel and the British historian David Irving were its theologians. With their distinctive flourish, Zundel and Irving attracted a lot of press—and earned a comfortable living—by promoting the movement’s core obscenity, that the Holocaust was a Jewish-inspired fraud.

In June, 1989, Droege introduced Bristow to Zundel and Irving as a security expert capable of shielding them from sometimes violent demonstrators. Bristow soon concluded that Zundel and Irving were, in a way, charlatans. Despite their public personae as the extreme right’s ideological standard bearers, privately Zundel and Irving were preoccupied with promoting their nit-witted version of history to anyone who could afford to buy their propaganda. “Honestly,” Bristow says, “they were just payday Nazis.”

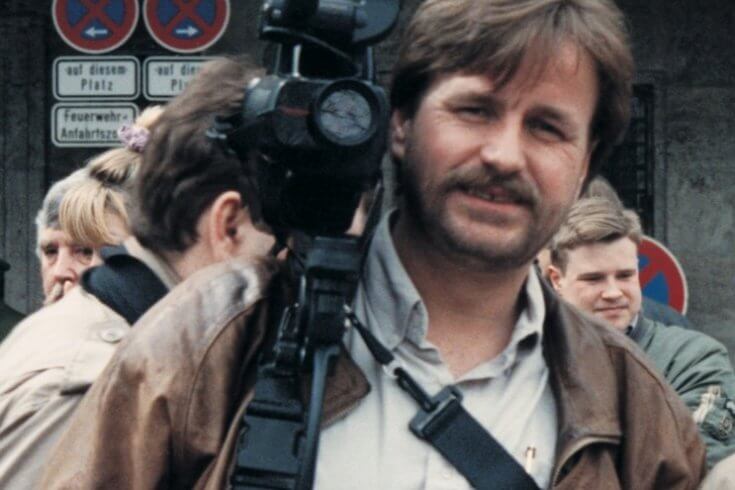

On Zundel’s recommendation, Bristow accompanied Irving to speeches the Holocaust denier gave in Toronto in late 1990. A remarkable picture at one event shows Bristow acting as Irving’s bodyguard while Irving sells his wares to about sixty followers.

Droege, meanwhile, was working hard to extend his burgeoning racist network. Early in 1991, he dispatched Bristow to meet with Terry Long, the head of the Canadian chapter of Aryan Nations, and Al Hooper, leader of the Aryan Resistance Movement in Western Canada. Any trepidation Bristow may have felt before meeting the gun-toting Long at his small farm in Caroline, Alberta, vanished after Long warmly welcomed him as Droege’s deputy. Long agreed to share his membership lists and help to set up a computer network through which white supremacists could quickly communicate with one another. Hooper agreed to provide Droege with the names of 180 members.

For Droege, the trip was a triumph, since it brought him closer to realizing his dream of creating an umbrella racist group in Canada under his own leadership. csis also thought the trip was a success, since Bristow had dutifully passed on the membership lists, enabling them to form a better picture of the scope and direction of Canada’s white supremacist movement. For his efforts, Bristow received a dual reward: csis allowed him to take a brief vacation to London, England. And Zundel and Droege asked him to join them on a trip to the Fatherland.

On March 20, 1991, more than 300 neo-Nazis and Holocaust deniers from around the globe, including Irving and Zundel, met in Munich, Germany. A celebratory, almost giddy air pervaded the gathering. As he had on the Libya trip, Bristow used his cover as security adviser to extensively videotape and photograph the event and key participants. But the racist powwow promptly broke up after riot police stormed in. Earlier, Zundel had been arrested and charged with slander for publishing material denying the Holocaust. (He is currently facing deportation to Germany and will probably stand trial on these outstanding charges if he is found by a federal court judge to be a threat to Canada’s national security.)

Worried that they were about to be arrested as well, Droege and Bristow returned to their cheap hotel room in Dachau, a short drive from Munich, to consider their next move. Droege decided that the last place the police would look for him would be in a concentration camp.

Dachau was the Third Reich’s first, and perhaps most infamous, forced-labour camp. As many as 200,000 Jews, political prisoners, homosexuals, and gypsies were murdered there by the Nazis, from 1933 to 1945. Each year, thousands of visitors pay homage to its victims. In late March, 1991, a group of Jewish schoolchildren, wearing yarmulkes, were walking silently through the camp’s barracks and exhibits when Droege arrived.

“This never fucking happened,” Droege shouted in English. “These little yips have to learn that this stuff is bullshit.” It was unclear, Bristow says, whether the children understood Droege’s taunts, but other visitors did and confronted him. The Heritage Front leader kept on laughing. Eventually, Bristow persuaded Droege to leave before the police arrived. Droege’s conduct was not a prank, says Bristow, but a true measure of the depth of his hatred of Jews: “For Droege, Dachau was an amusement park.”

From an intelligence-gathering perspective, the trip to Munich was a disappointment. Bristow had hoped that Zundel would introduce him to his major backers in Germany and Europe, but Zundel’s arrest prevented that. Bristow, however, did conclude, and reported to csis, that among European white-supremacists, Droege was a nobody.

In Canada, though, he was becoming a somebody, particularly in the eyes of the media. The Heritage Front and its leader were beginning to attract the attention he craved and he was adept at exploiting the media’s appetite for sensational news. He understood that racism, skinheads, and the perpetual prospect of violence were ingredients that journalists couldn’t easily resist.

In a well-choreographed performance, Droege formally launched the Heritage Front and unveiled its mission at a Toronto rally in September, 1991. Local and national television news programs and newspapers reported on the event. No leaflet could have generated that kind of attention and the Heritage Front quickly profited, as a burst of new members joined its ranks.

The publicity also caught the eye of Richard Butler, the messianic head of the Aryan Nations. Butler operated a twenty-acre compound in Hayden Lake, Idaho, as a sort of breeding ground for paramilitary white supremacists. Butler invited Droege to the compound in 1991. Droege and Terry Long suggested that Bristow go in his place. After consulting with his csis handler, Bristow agreed to the mission to identify Canadians who were attending the neo-Nazi boot camp.

Travelling alone to Hayden Lake was a risk for Bristow. If he was unmasked while inside the remote, heavily guarded compound, there was little csis or US authorities could do to save him. Sean Maguire welcomed Bristow and gave him a tour of the ranch. It was surreal. Families were picnicking, playing horseshoes, or attending “prayer” meetings. But beneath the veneer of civility ran a deep current of hate. No one seemed to embody that more completely or dangerously than Louis Beam, a diminutive racist from Texas who had spent time on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list for sedition and attempting to overthrow the US government. The charismatic Vietnam War veteran imported the notion of “leaderless resistance” into the white supremacist movement, encouraging small, independent cells to commit acts of terrorism without seeking the advice or consent of the movement’s leaders. Beam’s intent is to make infiltration and interdiction virtually impossible. (The Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh was reportedly a Beam disciple.)

Later, Beam spoke at the compound’s chapel. Listening to his “sermon,” Bristow says, was a profoundly disturbing experience. Indeed, he says, it was the first and only time in his long sojourn inside the bowels of the racist right that he felt afraid. Beam began in a hushed tone, building slowly to an awe-inspiring crescendo. “We believe [our children] have a right to a future. And if you don’t like that, then here’s some lead. Bam! Is that sedition? Is that conspiracy? Then so be it! Hallelujah! Hallelujah!” His audience rose and responded to the thundering call to arms with Nazi salutes.

That visit to Hayden Lake, Bristow says, crystallized Operation Governor’s raison d’être. Besides discovering that racist skinheads and white supremacists from Calgary and British Columbia had received training at Butler’s compound, Bristow understood that Droege, Butler, and Beam were methodically redrawing the racist landscape. Their vision was now taking shape in an alliance between violent white supremacists throughout North America.

American white supremacists were also paying courtesy calls in Canada. In mid-1992, Tom Metzger, the head of the murderous White Aryan Resistance (WAR), and his son John accepted Droege’s invitation to attend a Heritage Front rally in Toronto. The Metzgers were among the first American-based racists to use weekly radio and cable-television programs, as well as the Internet, a telephone “hateline,” and an e-mail newsletter to promote their message. Droege was well aware, Bristow says, that the Metzgers were headliners in the racist right and were guaranteed to draw a large crowd. The Metzgers did not disappoint, attracting well over a hundred supporters to the fundraising rally in late June. Once again, Bristow provided details of the Metzgers’ whereabouts to authorities, and as a result, they were scooped up by the police about two hours after the rally and subsequently deported. The widespread publicity triggered by their arrest had a salutary affect on Droege, Bristow says. The Heritage Front was now generating ink not only in Canada but in the United States. Droege’s racist enterprise was also beginning to attract the attention of anti-racist activists, who viewed the Heritage Front’s rise to prominence as a challenge. Groups like Klanbusters and Anti-Racist Action sprang up to confront Droege head on.

By early 1993, the Heritage Front and the anti-racist activists were heading towards an inevitable and violent collision. Skinheads inside the Heritage Front, restless with Droege’s press conferences, were itching for a fight. Anti-racist activists appeared ready to oblige. Signs of what lay ahead occurred outside a Toronto courthouse when more than five hundred anti-racist demonstrators clashed with mounted police as they tried to shepherd Heritage Front members into court.

Bristow insists he was facing an unenviable dilemma. As Droege’s deputy, he couldn’t be seen to be turning a blind eye to what the Heritage Front deemed to be enemy provocations. But as a government-paid agent, Bristow couldn’t promote or countenance a violent response. “I was walking a very thin tightrope,” he says.

The solution to his quandary was arguably the most controversial measure Bristow undertook during Operation Governor: he coordinated and participated in a campaign—with the knowledge and approval of his csis handler—to harass key anti-racist activists at home and at work. He dubbed the plan the “It” campaign. The aim was to single out anti-racists and threaten them until they “ratted out” the home telephone number of another activist. Until then, they were “it.”

Though the scheme may have tested the threshold of legality, Bristow vehemently defends it as better than the alternative. “I was trying to find a response that didn’t include out-of-control, escalating violence,” he says. “If I was wrong in the actions that I took, I must take responsibility for that… [and] I certainly regret any harm that might have been caused to people.”

Bristow’s defence of the “It” campaign sounds noble, but it also has a disingenuous ring to it. He prefers to call it an “annoyance” campaign, rather than a harassment campaign. He is adamant that proceeding with the “psyops” [psychological operations] was his only means of diffusing the combustible mixture of skinheads, testosterone, and hate. “No one had ever offered me an alternative plan to avoid the violence,” Bristow says. “So, it’s damned if I do, damned if I don’t.”

The campaign, at least temporarily, kept Heritage Front members from satisfying their urge to “crack a few heads.” But Bristow’s efforts to rein in the inherently violent nature of the group and its leader disintegrated in Ottawa on May 29, 1993. Bristow was in Toronto when baton-wielding police, five hundred anti-racist activists, and about sixty Heritage Front members, including Droege, clashed in wild, running street battles that spilled onto the steps of the city’s hallowed War Memorial.

The incident had an immediate effect inside the Heritage Front. Brewing discontent with Droege’s leadership, Bristow says, led to demands that the Front launch a sustained, violent offensive against its enemies. More ominously, a small group of young, unpredictable Front members established a splinter group that appeared ready to adopt the more radical tactics of Aryan Nations and WAR. Bristow heard disturbing reports that the gang was boasting about a plan to attack the offices of the Canadian Jewish Congress in North Toronto.

Whether it was mere bravado or not, Bristow believed they were capable of committing the assault and he provided his handler with an urgent threat assessment of the splinter group. Within twenty-four hours of his submitting the report, the gang had struck, robbing a bank and a doughnut shop (leading Bristow to ridicule them as the “French Cruller Gang”). He learned where the gang members were hiding out and alerted his handler to their whereabouts. When police arrested the suspects, they found a large cache of weapons, including sawed-off shotguns, and boxes of ammunition.

The swirl of events was exacting a toll on Bristow. He felt overwhelmed as he worked eighteen-hour days, strugling to keep abreast of events that appeared to be spiralling out of control. In the midst of the turmoil, Bristow sought refuge with friends and family. He decided to marry his girlfriend, keeping the wedding service a well-guarded secret from Droege and the rest of the group.

On the eve of their three-day honeymoon trip to New York City, Bristow told his comrades in the Heritage Front that he would be out of town for several days, job-hunting. But Bristow couldn’t escape his ties to the group. When the newlyweds arrived at New York’s La Guardia airport, brusque US immigration officials briefly detained him for questioning.

Bristow returned home to a big problem. Droege had been charged with aggravated assault stemming from another racially motivated scuffle in Toronto. If Droege was convicted, Bristow, a government-paid agent, would probably be acclaimed leader of the Heritage Front. That was unacceptable. Bristow, too, was running out of steam and yearned to resume a “normal” life.

Through skill and astute planning, he had survived largely unscathed. But the risk of exposure was still very real and the consequences of a mistake or betrayal would now affect his wife and child. It was a burden Bristow was no longer prepared to carry. He and his handler began designing an exit strategy.

In early 1994, as Operation Governor entered its fifth year, Bristow noticed a marked change in Droege. Potentially facing yet another lengthy jail spell, the racist right’s “hero,” Bristow says, suddenly seemed to lose the will to fight any more. At the same time, the Heritage Front appeared to be imploding.

Finally, in late March, 1994, Bristow ended his involvement in Operation Governor. Before departing, he helped his handler draft a batch of threat assessments on key Heritage Front members and the white supremacist movement as a whole. They concluded that the impetus behind the Front was fading. Its telephone hotline had been shut down by court order; key racists were facing serious criminal charges; Terry Long had vanished; Andrews and his “Androids” were more laughed at than feared, while others were abandoning the movement altogether.

“It was time to go,” Bristow says.

Bristow chose a quiet stretch of Toronto’s beachfront to tell Droege that he was reluctantly leaving the movement to take a job in eastern Canada. It was a cover story that would allow Bristow to resurrect his role in Operation Governor if circumstances demanded it.

“You’re probably one of the best and closest friends I have ever had,” Droege muttered, as tears filled his eyes.

“Always guerreros? ” Bristow said.

“Always,” Droege replied, before hugging his former lieutenant.

It was the final act in a sham friendship that had spanned several years and three continents, and encompassed countless lies. Recalling his performance that day, Bristow beams with pride. “I was good. Right up to the end. Hook, line, and sinker. Game, set, and match. Never, ever think for a moment that I ever suffered from target love. This was business.”

Days later, Bristow bade his csis handler a more sincere adieu at a hotel in downtown Toronto. A satisfying sense of accomplishment permeated the meeting, as the pair shared war stories over an expensive steak dinner. The talk turned to the future and Bristow rebuffed an offer to pave his way into the espionage agency. Then, with a firm handshake and a tinge of sadness, Bristow walked out of the room and out of Operation Governor. Or so he thought.

Just weeks later, Bill Dunphy called. Bristow became a hunted man the day that Dunphy exposed his ties to csis on the front page of the Toronto Sun in August, 1994. He knew that the violent racists he had duped so convincingly and for so long would try to exact some measure of revenge.

At first, Bristow and his small family were sequestered in a furnished, three-bedroom apartment-hotel in Toronto. They remained in seclusion for nearly two weeks while csis dispatched a crisis team, including doctors, psychologists, even a public-relations expert, to the safe house to help Bristow deal with the avalanche of unsubstantiated allegations that promptly filled the press. “The media assassinated me,” Bristow says.

In late September, Bristow and his family boarded a crowded Air Canada flight to Calgary. Their final destination was the resort town of Jasper, where they hoped to find sanctuary. As they leaned back in their economy-class seats, the in-flight television news began and a story about “The Heritage Front Affair” flickered on a tiny, dropdown screen. Bristow sighed.

The ten-day getaway of hiking, bicycle trips, and soothing dips in a hot tub buoyed Bristow’s spirits. But by late October he realized that returning to Toronto was impossible. The media had swarmed over his suburban home and csis worried that white supremacists were still lying in wait. Reluctantly, Bristow sold his home, as well as his stake in a new publishing venture. csis gave him a new identity and found him a home in an Edmonton suburb where a maze of cookie-cutter homes offered the family a chance at anonymity. Bristow went back to school to study accounting.

By Christmas, Bristow and his family were settled into their new home and looking forward to a life far from the suffocating scrutiny of reporters. In March, 1995, his wife’s stepfather died; Bristow flew to Toronto to attend the funeral, where he was an honorary pallbearer. Bristow’s father-in-law was a Jew and the funeral service took place at a Mississauga synagogue. Wearing a yarmulke, Bristow walked solemnly in front of the casket as it was carried out of the synagogue and into a waiting hearse. “I had a great deal of respect for my father-in-law,” Bristow says. “He was a decent man who stood by me without question.”

Days later, Bristow returned to Edmonton, But he could not escape the Toronto media. On an April morning in 1995, as he emerged from a local hospital after a round of physiotherapy to mend a broken leg, shattered in an ice-skating accident, Bristow was confronted by Dale Brazao, a Toronto Star reporter. Bristow brushed by Brazao, refusing to comment. When he arrived home, Bristow told his wife about the encounter.

“Will they ever go away? ” she moaned. Early the following morning, the Bristows were on the move again, this time driving to Calgary to meet a hastily reassembled csis crisis team to consider their next move.

That decision became more difficult when Brazao’s story hit newsstands, as it contained details about Bristow’s new identity (including his new name) and pictures of his new home. What angered Bristow most, however, was the Toronto Star’s decision to publish his wife’s name and photograph.

“It was beyond contempt,” Bristow says bitterly.

But Brazao’s “exposé” died a quick death. On April 20—Adolf Hitler’s birthday—the media’s attention was consumed by another, more pressing story: the Oklahoma City bombing. White supremacist Timothy McVeigh had parked a truck full of explosives in front of a federal building in Oklahoma City. When the homemade bomb detonated, the building partially collapsed and more than 300 men, women, and children perished. The terrorist attack was conceived, planned, and committed by the very racists Bristow had once spied upon.

Bristow and his family decided that they were through running. After spending several weeks in an Edmonton apartment, they returned home to try, once again, to get on with their lives. But Bristow says his marriage never recovered from the exposure of his wife’s identity in Canada’s largest newspaper. The stress and uncertainty of their lives in the aftermath of his covert work finally led to an amicable divorce in 2000.

Last June, Grant Bristow addressed members of the Canadian Jewish Congress at its sprawling headquarters in north Toronto. For days, Bristow had laboured over his speech, knowing it was an opportunity to seek the understanding of a community that still questioned his motives and deeds as a spy. After a kosher buffet dinner, Bernie Farber, the CJC’s executive director for Ontario, ushered the guests into a large adjoining room. Bristow took his place at the head table.

In his half-hour speech, Bristow reviewed the long arc of Operation Governor, and the threat that hate-mongers such as Wolfgang Droege and other white supremacists still posed. He ended by recalling his friendship with Maurice Klagsbrun and his haunting story of loss and remembrance.

The speech was met by sustained applause, muffled weeping and, finally, a standing ovation. Bristow took a few steps back, as if recoiling from the response, while, at the same time, trying to absorb the profundity of the moment.

Professor Irving Abella, a former president of the CJC and a respected historian, spoke next.

“This was a truly historic event,” Abella said. “I think what was most important about this evening was how heroic this man was. Both as a Jew, and an historian, I wish to thank you, Grant Bristow, for your courage in coming forward [and] for the truly important role you played in those risky years of ten years ago.”

Bristow was overwhelmed. He had sought understanding from a people who were and are routinely victimized by the purveyors of hate he had once spied upon. In the end, he received much more. He received their respect and admiration.

A day later, the warm afterglow of his extraordinary meeting with the CJC was extinguished. While enjoying a coffee at a sidewalk café in Toronto’s Beaches district, Bristow noticed a motorcycle slowing to a crawl almost directly in front of him. He bolted from his seat, his face ashen. “It’s Wolfgang,” he whispered to his companion. Bristow’s nervousness subsided only when Droege’s leather-clad frame faded into the distance.

That a single white supremacist can still trigger such apprehension in Bristow is instructive. He knows how much the neo-Nazi movement has changed. He knows that numbers, organization, and high-profile leaders are largely irrelevant to today’s militant white supremacists. Neo-Nazis have altered their tactics. Like the Oklahoma City bomber, Timothy McVeigh, they have gravitated to the notion of leaderless resistance, making their ranks more difficult to penetrate. All the extremists require now to vent their hatred with cataclysmic consequences is the will and the opportunity.

Grant Bristow knows, better than most, that the only unknown is how many more Timothy McVeighs are out there, poised to act.