Toronto police were prepared for anything on the evening of July 4, 1938. The city had been buzzing for weeks about a controversial upcoming rally at Massey Hall, where three leaders of Canadian fascist organizations planned to celebrate their merger into the National Unity Party. Police had already prevented two separate riots in June, when antifascists tried to disrupt fascist meetings through obstruction, insults, and hurled rotten tomatoes. The Massey Hall event promised to be just as disruptive: antifascists had already postered downtown with flyers beseeching direct action to “keep the blackshirt gangsters out of Toronto.” According to the Globe and Mail, the fascists warned that they would be deploying 100 “stormtroopers” to protect themselves. When July 4 came, thousands of Torontonians took to the streets.

The antifascist protesters weren’t just radicals. Along with the communists, Trotskyists, and anarchists, there were liberals, conservatives, social democrats, and social gospellers. By 1938, respectable Canadian opinion had grown intolerant of the unchecked expansionist aggression in Europe and the mobilization of domestic fascist organizations. Open opposition to fascism, once a fringe position, was going mainstream.

Over eighty years later, we are witnessing a resurgence of antisemitic, xenophobic, racist, and fascist activity at home and abroad. At the same time, the antifascist consensus that slowly percolated and woke Canadians up to the fascist threat in the 1930s has decayed, lulled into a false sense of security by the end of the Cold War. As the rising tide of hatred slowly creeps up, it’s worth asking why over 11,000 Torontonians left their homes to demonstrate on a summer night in 1938.

A Canadian antifascist consensus was not a foregone conclusion in the early 1930s. Opposition to fascism was initially a community concern; Italian antifascists battled the influence of Mussolini in their community, while Jewish and left-wing Canadians reacted to the Nazi persecution of Jewish and left-wing Germans through demonstrations, boycotts, and fundraising campaigns. The 1935 Italian invasion of the Ethiopian Empire drew protest by Black Canadians, as reported in the Globe, and the 1936 fascist coup in Spain galvanized the left. Although many Canadians disapproved of fascist aggression abroad, widespread reluctance to enter another war outweighed the desire for action.

Fear of communism prevented many from recognizing fascism as an immediate threat. Mussolini’s 1922 takeover in Italy and the perceived order it brought in the face of potential revolution had the support of many Canadians—sympathies that were echoed with when Hitler was handed power in Germany, eleven years later. Some conservatives, like future Ontario premier George A. Drew, saw fascism as a potential ally in the struggle against communism, while the RCMP, preferring to focus on anticommunist efforts, did not include reports of domestic fascists in its security bulletin until 1937.

The slow development of an antifascist consensus did not mean that Canadian society was becoming more tolerant. Xenophobic and nativist sentiment, stoked by the deprivations of the Great Depression, Anglo-Saxon assumptions of racial superiority, and non-Anglophone immigration, were common. Canadians grew more antisemitic as the decade unfolded, even as the threat of fascism became more apparent. In 1933, Ontario would see several Swastika Clubs founded to coordinate harassment of local Jews, a campaign that would culminate in a Jewish and Italian baseball team fighting back during the infamous Christie Pits riot in Toronto. In 1938, Toronto United Church reverend Gordon Domm, in a letter to the editor published by the Globe and Mail, diagnosed a “dormant” antisemitism “among Canadians of all ranks, which, if the stage is thus cleverly set,” could “threaten our whole land.”

Canadian fascism thrived on antisemitism and anticommunism. One of the largest domestic fascist organizations was the Quebec-based Parti national social chrétien (PNSC), run by Adrien Arcand, who openly admired Hitler and Mussolini and blamed Jews for the world’s problems in his publications. By 1937, the swastika-clad PNSC had roughly 1,000 card-carrying members, who were openly drilling and organizing as uniformed “blueshirts,” akin to the paramilitary Nazi brownshirts and Italian blackshirts. Emboldened by fascist aggression in Europe and a major fascist rally in New York City, on December 31, 1937, Arcand declared that he would spread the ideology through a series of “great rallies.” In March, Arcand announced that the PNSC would be merging with other Canadian fascist groups to form a party with federal ambitions and that a party congress would be held to select the new organization’s leader.

When Canadian fascists chose Kingston, Ontario, as the site of their convention, opposition came from established corners. Mayor H. A. Stewart and Kingston city council passed a resolution stating that the fascists were “not only unwanted in Kingston, but would not be permitted to hold meetings in any public buildings, nor would any public parade or demonstration be permitted,” a position supported by the police commission, the Canadian Legion, the Orange Order, and several Queen’s University professors. Arcand responded by booking Massey Hall in Toronto.

A minor free-speech controversy broke out in response to the fascists booking Massey Hall. Mayor Ralph Day (himself on the board of the venue) claimed that he could not legally stop the rally but pressured Massey Hall trustees to cancel. The Globe and Mail and the Toronto Star published editorials in defence of the fascists’ right to rent a private venue, but not all of their readers agreed. According to a letter to the Star, Day’s stance had “the support of all progressive people” in a “period when, throughout the world, democratic institutions are being reduced to ashes.” A letter to the Toronto Telegram highlighted the suppression of speech in fascist countries, arguing that “it is demagogy of this kind that democratic people must fight whenever it shows its ugly head.” Alderman George Granell went beyond silencing, arguing that Liberal and Conservative party members should “unite and throw these people right out of the country.”

Ultimately, Arcand and his fascists secretly held a small convention for the leadership on July 1, slipping quietly into Kingston, where journalists, local police, and plainclothes RCMP officers patrolled the streets looking for the meeting or for public disturbances. The fascists elected Arcand leader of the new party and issued a sarcastic message of gratitude to city council for its “courtesy.” That night, the fascists proceeded to a hotel in Toronto, where they announced to the press the formation of the National Unity Party (NUP), open to all Canadians with a few “exceptions,” including Asian and Jewish people.

It’s commonly argued that the press should ignore domestic fascist movements lest it provide momentum and exposure to these nascent hate groups. However, it was the extensive coverage of Canadian fascists that helped many recognize how close to home the threat was. No single issue served as a wake-up call, but the events of the decade contributed to a sense of crisis: the escalation of antisemitic laws and violence in Germany, the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, the Japanese invasion of China, and the overthrow of a democratically elected government in Spain. While Canadians learned about the budding Canadian führer in their midst in 1938, news of Hitler’s Anschluss of Austria, annexationist designs on Czechoslovakia, and attempts by a Nazi shell company to purchase Anticosti Island, in Quebec, were also reaching the front page. Suddenly the Canadian fascists didn’t seem so harmless, leading journalist Frederick Edwards to observe, in Maclean’s, that “the Hitler triumph spells an Arcand disaster.”

By 1938, conservative publications like the Toronto Evening Telegram, which in 1933 had claimed that reports of antisemitic violence in Nazi Germany were exaggerated, were openly condemning domestic and international fascism. Former prime minister R. B. Bennett, whose 1930 campaign had provided funding to Arcand, made a speech in the House of Commons drawing attention to the threat posed by Canadian fascism.

Even military opinion was turning—news that four or five members of the Royal Canadian Artillery had attended a fascist meeting in Toronto, in uniform, that June raised furor among veterans and civilians alike, and the Canadian Corps Association demanded that the federal government begin a Royal Commission into Nazi activities in Canada. In addition to a new name, the NUP attempted to soften its image by replacing the swastika with a flame reminiscent of the badges worn by a Canadian veteran’s association. This move only infuriated the Canadian Corps, which “emphatically” protested the NUP’s attempt to appropriate its symbol. This shift was particularly important as veterans and the military were often targeted by fascist organizations for recruitment.

The NUP rally took place on July 4, with several police detachments protecting Massey Hall. Entry was restricted to the roughly 1,200 ticket-holding attendees, who were greeted by a mélange of British and fascist imagery: blue-shirted goons standing in formation, streamers inscribed with phrases like “God Save Our King” and “Canada for the Canadians,” a table draped in a Union flag, arms adorned with swastika armbands raised in salute. After several speeches by NUP delegates that denounced, as reported by the Toronto Evening Telegram, “Jews and selfish politicians” and the “reeking carcass” of democracy, Arcand took the stage. He claimed that Jews were trying to conquer Canada through the “Red movement” and promised to recover Canada from “the red clutches of Moscow and international Jewry.” Hecklers were violently ejected during the rally after loudly denouncing Arcand’s antisemitism.

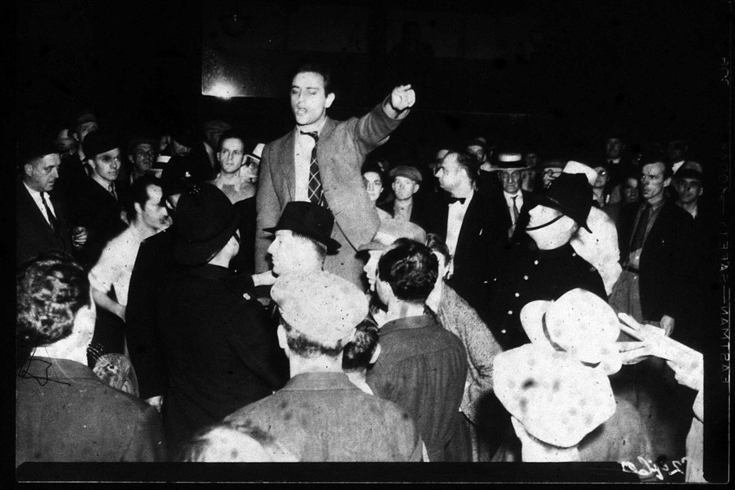

Up the street from Massey Hall, a direct-action protest organized by the Provisional Committee for Anti-Fascist Action raged. The committee was an alliance organized by the Trotskyist League for a Revolutionary Workers’ Party and involved the anarchist Libertarian Group, the Yiddish-speaking Workmen’s Circle, trade unionists, and an association of unemployed workers. Between 400 and 900 individuals listened to Trotskyist firebrands, including Spanish Civil War veteran William Krehm, urge the crowd to “crush those rotten Fascists.” Mounted police broke up the meeting after the speakers refused to stop and allegedly threatened to march on Massey Hall. Krehm and three of his associates were arrested, and the crowd was dispersed.

Trotskyists, anarchists, and Jewish radicals were not the only groups protesting the NUP that night. Farther up Yonge Street, the Canadian League for Peace and Democracy (CLPD), a politically diverse body organized by the Communist Party of Canada (CPC), held a rally at Maple Leaf Gardens. The CPC was actively trying to build a popular front and democratic alliance among a broad range of former political rivals, an effort that involved explicitly accommodating middle-class progressives and liberals through organizations like the CLPD. The project was successful: around 10,000 gathered that night to hear recently returned former American ambassador to Germany William E. Dodd speak—he urged unity and cooperation among democracies in the face of the fascist threat.

The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) held its own peaceful counterprotest at Queen’s Park, where roughly 500 people gathered to hear future mayor William Dennison “expose the real nature of fascism” and present a “Socialist alternative” to the Communist Party. Aware of the Anti-Fascist Action protest, CCF leadership claimed to have organized the gathering to “draw people away from the Fascist meeting in Massey Hall,” where they might “lose their tempers.”

Despite the strong ideological disagreements and tactical differences between the various groups protesting the NUP, they found themselves occupying similar ground within an emerging consensus around fascism. The following year, when the NUP attempted to host a second Massey Hall rally, a meeting of Gallipoli veterans—not typically left-wing individuals—enthusiastically cheered a reverend and army captain’s suggestion that they deplatform the speakers. The consensus became unavoidable state policy when Canada joined the Second World War. In May 1940, Arcand was arrested for “plotting to overthrow the state,” the NUP was banned, and its members were sent to an internment camp in Ontario.

Fascism has evolved in the twenty-first century, adapting to new technologies and developing new recruitment tactics. However, many of its mobilizing passions—racial or national grievance, a sense of overwhelming crisis, widespread disillusionment, anxieties about perceived societal decline, and a desire for rebirth—remain the same and are fuelling far-right movements around the world. Although Canadian fascist parties never grew beyond a few thousand members, their ability to operate without mainstream opposition until the late 1930s legitimized them as a political alternative that had the potential to capitalize on a moment of domestic crisis. What ultimately prevented fascism’s growth prior to the war was the development of an antifascist consensus.

Building an antifascist coalition is not easy. It involves mutual accommodation between political rivals and does not pretend to resolve major differences. The most successful attempts at building an antifascist consensus emerged when the Communist Party of Canada jettisoned the hardline sectarianism and violence of earlier approaches and formed alliances with progressives in the middle class, who were in turn willing to hold their noses and work with radical organizations. Antifascists as disparate as Stalinists, Trotskyists, and conservatives were hardly political bedfellows, but all found themselves actively mobilizing against a common enemy.

The prewar antifascist consensus provided the atmosphere where politically diverse, cross-community alliances could be built along common understandings: that democracy is delicate and at risk, that our civil and minority rights can be lost, and that some fights are more important than others. In July 1938, that consensus helped a diverse mass of Torontonians unite to emphatically reject the fascists.