I‘ve always written about kids and education. People used to challenge my right: “You don’t have kids,” they’d say. I could only answer, “But I was a kid.” Teaching is also a thing everyone has the right to opine about, not because everyone has been a teacher, but because everyone has been taught.

The education discussion tends to focus on big issues: human nature, relations between the biological unit of the family and social units like the nation, the values that ground personal and collective behaviour, the good society, the demands of citizenship. When I was a kid in the 1950s, writers like Paul Goodman (Growing Up Absurd ) and Edgar Z. Friedenberg (Coming of Age in America) went into schools like classical anthropologists searching for the noble savage or like anarchists who travelled Europe in the late nineteenth century, stirring up revolution whenever their train stopped long enough. Starting in the 1960s, Jonathan Kozol wrote bestsellers about US ghetto classrooms, like a war correspondent at the front. For twenty years, I worked for an alternative journal now called This Magazine, which began life as a homespun publication called This Magazine is About Schools. That was when education still engendered grand, resonant debates.

One effect of the deficit hysteria and budget slashing of the late twentieth century was to throttle discussion about public education. People with a passion for it were reduced to fighting rearguard actions to save what they could, holding bake sales so the kids would have textbooks or pencils. People who would have been happier attacking the system in order to humanize it were forced to fight for its mere existence. It has been everyone’s loss. Education is always a mess; it’s always damaging kids and others. It needs critics even more than it needs defenders.

I student-taught at my Toronto synagogue from age seventeen. We made lesson plans and used audiovisual aids like film strips. During university, I worked at summer camps. Inspired by A. S. Neill’s book on his free school in England, Summerhill, I tried to abolish cabin cleanup. For twenty-nine years, I’ve taught a half-course in Canadian Studies at the University of Toronto. I run it as a discussion, though it has grown from 20 to 175 students. “That class was real ’60s,” said a former student. I prefer to think of it as Socratic. When I taught Plato’s The Republic to undergrads on Long Island in the vrai sixties, I told them the basis of political authority was: “They got the guns, man!” My eight-year-old, Gideon, heard me say that while reminiscing with old friends. He cracked up. “I can’t believe you said, ‘They got guns, man! ‘” I hope it’s the ‘man’ that convulsed him, but I fear it’s the pomposity.

Gideon is my only kid. He started attending private daycare at ten months. It seemed tragically early, but he thrived. There were kids of many ages and they looked after each other. Some, like Gideon, attended all day; others, after school or just for lunch. (“Graduates” dropped in sometimes because they still felt attached to the place.) For Gideon, daycare may have helped compensate for not having siblings or an accessible extended family. He formed intense friendships, many of which he’s maintained. I deduce from this that you never know what value a kid will glean from a setting. In that way education is like dating: no one knows what they really want until they get it.

Gideon went to a Montessori school for kindergarten. There, each kid works separately, on skills such as math and geography or a physical task such as pouring. The teacher deals with one student, teaching a new skill until the kid grasps it; then the kid continues alone, or aided by an older kid, until he’s mastered it; then the kid moves on to something new. For the teacher it looks exhausting. She keeps glancing around to check on others. Occasionally, a kid comes to her with a problem, and she deals with it. There is no lockstep learning, no time-limited and testing-based units of study. It is total decentralization. Kids work at their own pace, and eventually everyone covers the same skill sets. The teacher keeps track. It is collective and individual, and there are few discipline problems since there is no attempt to keep everyone on the same track. It only looks anarchic; it’s actually highly structured and task-driven. The kids respond positively, and I see little reason why this approach couldn’t be applied to public systems.

Maria Montessori designed her teaching style for slum kids in Italy a century ago, though at Gideon’s school suvs lined up at the end of a day to pick up the kids. He loved his first year there but not the second; the difference was his reaction to two different teachers. Other kids had the reverse experience with the same teachers. From this, I deduce that regardless of method, the teacher is central. I mean this as more than the pablum it sounds. I’ll return to it.

Gideon went to Clinton, our local public school, for grade one. Some of his old daycare friends were there, he wanted to join them, and there was a financial consideration, but the main point was educational. What you learn in the public system is what the world you live in is like and that you are a part of it. That’s because the public system must let everyone in. Some kids might bully you, and the school should help you cope with that. In the yard after school, a wayward kid might kill a butterfly that your class carefully raised from pupa stage — enraging parents, but the kids understand because, after all, so-and-so did it, and he’s sort of like that. Sending a kid into the public system, for those who can afford otherwise, isn’t an altruistic choice to support public education, or it shouldn’t be. I think Gideon sensed that Clinton was a “real school,” in the sense of a public institution that was a part of the larger world in which we live, and that’s why he wanted to go. He strutted through the halls in a way he hadn’t at Montessori.

But the mystery that is teaching is most striking for me at Gideon’s karate classes. I’ve sat through hundreds at Northern Karate Schools, twice a week, never bored, rapt each time trying to figure out why this teaching is so good. Gideon went briefly to another karate school that was quasi-military — lots of Sir, yes sir — but it didn’t take. Northern Karate has none of that, though it’s disciplined and highly structured. He can attend any of several classes each day of the week. Teachers vary along with the composition of each class, so his experience doesn’t depend on one teacher. Classes are brief: usually thirty minutes, and drills shift often, so attention doesn’t flag. But at bottom, it’s the teachers.

They have vastly different personalities. Dominic is stocky and ebullient, with a voice like Aaron Neville’s. Ricky Bonaparte (great name) is intense and demanding. “Ricky makes you want to work hard,” says Gideon. Vince is methodical. Claire is maternal. They were well trained in conveying specific karate techniques but, says Andrea, another teacher, they each had to work out an underlying approach for themselves. This is a kind of teaching where the teachers are taught to find their own way.

The teachers pay the same attention to three-year-olds as they do to black belts. When the students are taken through moves or stances or full routines (katas) that they’ve done thousands of times, there is always something to learn. Noam Chomsky was once asked on cbc-tv if he ever got tired repeating the same points about politics year after year. He chuckled, adjusted a pesky earpiece, and said, “No, after we finish this interview, I’m going into a linguistics seminar where we’ll discuss issues I’ve been thinking about a lot longer. There’s always something to learn.”

Teaching is one of the most basic human activities, like breathing and seeing. There’s no end to it, just deeper depths. The best part about watching Gideon’s karate teachers is that I can’t nail down why they are so effective. It’s fun, I think, but there’s more to it than that. Or: they like kids. But the nub keeps slipping away. That’s why it’s teaching, a kind of activity that exists in the doing and that constantly reshapes according to context. This doesn’t mean that method doesn’t matter. But there is always that other, independent variable: the relationship between teacher and student.

It is like the mystery of therapy. Teaching and therapy are the two remaining institutional redoubts of the oral tradition in our society. Aside from them, the oral tradition survives mainly in gossip, chit-chat, and folklore. Aside from teaching and therapy, the written rules. No one has yet succeeded in reducing teaching or therapy to written form, despite correspondence courses and self-help books. It doesn’t even require speech; silence can be the best teacher. Some of the most famed cases involve the sage or therapist saying nothing at a crucial moment.

Pedagogy is unavoidable, as is a curriculum. But it is in the nature of oral discourse that it cannot have definitive rules or a stable end point. You can offer these provisionally but there is no authoritative method or conclusion, any more than there is in a friendship, a marriage, or therapy. The relationship can stray somewhere unexpected; it can stop or unfold further. Teaching is essentially open-ended, because it belongs among those normal human activities that are embedded in time, and can’t be extracted from their unfolding process and formalized. It is in their nature that any human being can do them and in some form, everyone does.

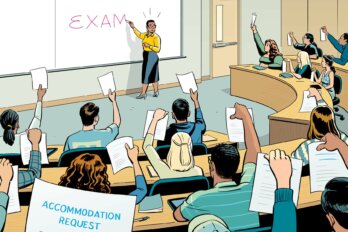

In this light — that teaching is a normal human function — I’d like to make a modest proposal: why not extend teaching duty, in an assistant capacity, to members of the community in order to help solve the classroom crisis everyone talks about? To the extent that schools require extra help in the classroom, citizens would be called on to serve, as they are in jury duty, with similar allowances for being excused and/or omitted. These community members would help so that teachers themselves could spend more time with individual students, as in Montessori classrooms. This would address the problems of class size and also of discipline. Let me linger over discipline.

It is impossible to run a teaching institution, or any institution, without some element of order and mutual respect. Reports in the spring from C. W. Jefferys Collegiate Institute in Toronto, where a fatal shooting occurred, and from elsewhere, tell of students threatening teachers, ignoring them, verbally and physically abusing them. This is not just an education issue, it is a sign of serious social breakdown.

In the past, order was generally maintained through a social fabric that was hierarchical and patriarchal. It included religion, a moral code, parental authority, and sanctions like the threat of hell, all of it internalized in a sense of guilt and shame over violations. It worked in the sense that it largely kept the lid on violent impulses or channelled them elsewhere, but the human and emotional costs were monstrous. People were dulled to their own experiences and each other. I would not want to restore this set of constraints if we could, and we can’t. Particular players — parents, schools, teachers, courts, governments — can try to impose controls and limits, but they will not be nearly as effective as they were within a total framework that no longer exists. The issue now is: can our society devise a set of social controls that permits learning but does not require severe repression and an impossible return to the undesirable framework of earlier eras?

Of what use would the conscription of classroom citizen assistants be in this respect? One of the serious causes of the breakdown is that many youth believe their surrounding society doesn’t really give a damn, and does little to ease their way through school and beyond. Their job prospects are uncertain, and they are told to prepare for constant change. This amounts to saying, “You’re on your own.” The models they see for success in the adult world tend to be grandiose and egocentric, and lack social purpose or contribution. The presence of community members in classrooms would offset their sense that society doesn’t care, because it would represent a social commitment, in personal form. (My Uncle Eddie, a cosmetic surgeon, used to go into British Columbia prisons to operate on inmates who felt a different look might help them change. The results were good, and the warden said that this was mostly because the convicts knew Eddie wanted to be there.) Today, adult society appears to have largely opted out of its responsibilities to coming generations. Youth get this and respond variously, from violence to sullenness. A way for adults to address this response would be to opt back in.

Besides, I don’t think teaching should be a full-time activity. It is too demanding and too normal. Teaching a two-hour university class is exhausting. What can it mean to teach a room full of kids, all day, five days a week? Summers off don’t solve the problem. The kids teem back in September. Teachers should teach only part-time because teaching, like eating, is a part-time activity. Then they could teach at their best. Since this may have to await a more utopian future, the least the rest of us can do for now is to get in there and share the burden, as well as the vast reward.