During the first half of the 20th century, when the British still occupied India and a nationalist movement had erupted against the British Empire, sundry U.S. journalists were dispatched to observe the scene and interview Mahatma Gandhi. “What,” one of them asked the Indian leader, “do you think of Western civilization?” The old fox smiled. “It would be a good idea,” he replied. Seventy-five years later, Iraqis suffering the abuses of an oppressive first year under the U.S. occupation would probably endorse Gandhi’s sentiment.

To sell the Iraq instalment of the war against terrorism, the U.S. had justified the war as necessary to free the good and common people from a tyrant. Once removed, and with the benefit not of foreign nation-builders but of bureaucrats to ease the transition, the path would clear, swords could be turned into ploughshares, and the desert would bloom in a transformed and democratized Middle East. If at home President Bush and his cadre of acolytes were merchants of fear, on the road, to justify foreign adventures, Donald Rumsfeld et al. were merchants of hope.

Some in the West hoped that the U.S. intervention in Iraq would lead to democracy. Few in Iraq suffered such illusions. They were only too well aware that at the height of the repression in Iraq, Saddam Hussein had been a favoured Western ally, barely criticized in the U.S. media. And what has happened has confirmed Iraqi doubts. At a single nod from the conquerors, time-servers such as Ahmed Chalabi (aptly described in The New Yorker as the man “who sold the war”) are reduced to primitive obscurity. Saddam’s former ally (whom Saddam later tried to have killed), the ex-Baathist Iyad Allawi, is the new puppet prime minister. And all this is welcomed by the “international community,” showing once again that it is the wealth and military strength of the U.S. that enables them to buy the services of poorer and weaker states.

In any case, with the revelations of the abuses at prisons in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Cuba, the U.S. has lost whatever moral authority it purported to have, and the result is a genuine clash of civilizations – one that could have been easily avoided.

In the spring of 1917, when the British entered Iraq, the statement of purpose was similarly virtuous: the generals and their battalions came not as conquerors but as liberators. To allow that controlling Iraq back then was part of a grander design to secure the Middle East as a European access-route to Asia would have divested the occupying force of the moral authority necessary for success. Always, the occupier requires a mask: the benign bestower of a better life, a better “civilization.”

The British, of course, had assets the U.S. lacks. One was a long and storied colonial legacy rooted in a commitment to settlement. Legions decamped from the British Isles to populate the globe. In so doing, they – at home, the marginalized, the impoverished, the outcasts; away, the pioneers, the entrepreneurs, the pirates – contributed mightily to another great asset: through the ingenious workings of mercantilism, they filled the treasury of Westminster with ever-ballooning capital and established Britain as the world’s banker. Most importantly, the British embraced their empire as righteous, utilitarian, and a civilizing force.

In contrast, latter-day Americans suffer from intellectual and historical amnesia, and a sense of denial bordering on the delusional. Despite U.S. insistence to the contrary, we have, for the first time in human history, the existence of a single empire, and it is the American Empire at the beginning of the “New American Century.” The U.S. military is stationed in 138 countries, and, in key geopolitical regions such as the Middle East, it secures strategic partnerships through the provision of defence services, military hardware, and corporate investment. This is especially true in Israel and Saudi Arabia, the Middle Eastern bête noires for Muslim fundamentalists. Israel is a false economy, more and more dependent on Western capital inflows and by the day losing its claim to being the region’s only democracy. In Saudi Arabia, U.S. corporate investments exceed $400 million a year, and U.S. companies have more than two hundred joint ventures (principally in the petrochemical and energy sectors) with Saudi Arabian companies. Certainly support for Israel opens the doors to Islamic and Arab charges that the West aids and abets the unlawful occupation and confinement of Palestinians. But, post-Iraq, all indications now suggest that the long-standing reciprocity between the U.S. and the House of Saud – to Islamic critics, oil in exchange for military bases in the home of Mecca and Medina – will result in Saudi Arabia’s becoming the new hotbed and target of Islamic militancy.

In the absence of a system wherein the financial benefits of foreign investment accrue directly to the U.S. treasury, the costs of maintaining and expanding this empire – notwithstanding the U.S.’s status as the world’s largest debtor nation, the present administration appears committed to military budgets in excess of the next largest fifteen nations combined – should be the key issue in the upcoming U.S. presidential election. What, after all, is this global overreach putting at risk? If the economists are correct, how can social-security cheques, state medical insurance, the welfare state, etc., be sustained in the face of a balance sheet that reads “$45 trillion in the hole”? But, given the Administration’s refusal to use the “E” word, President Bush’s beliefs in divine guidance and “might is right,” and only faint challenges from American liberals to U.S. imperial aspirations, it is hard to imagine a change of course.

The most recent evidence of historical amnesia and a messiah complex lies in the lack of a measured exit strategy following “Operation Iraqi Freedom,” a war whose rapid result could have been guessed at by grade-school children. (Tony Blair knew that it would be a long haul, and the complicity in this charade of the British prime minister, whose country’s occupation of Iraq lurched on until 1955, proves that the diseases of blind faith and hubris have spread across the Atlantic.) But there is more to it. The absence of planning bespeaks a collective mind existing in a permanent present, and an adolescent insistence that “history begins with us.”

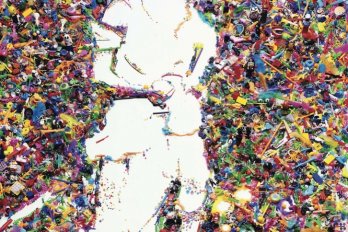

Contributing to this permanent present are television and the Internet – two “assets” the British were free of – and it is these tools of communication that have caused the U.S. to lose both the propaganda war and its moral authority. (After Gulf War I, embedding journalists was a brilliant strategic ploy, which, with rare exceptions, successfully contained the story for the homeland audience. In hindsight, this may have been the only “mission accomplished.”) In the interregnum between President Bush’s proclamation of victory and the day of uneasy transition to a dubious Iraqi self-rule, the bombs and body counts continued to soar, and the negative news became a daily headline. The image is more powerful than the word, and matters reached their nadir when the torture photographs from the Abu Ghraib prison were broadcast on Arab television and released over the Internet. The damage could not be controlled; the mask was off. On the ground, the liberators suddenly looked no better than the Baathist thugs of Saddam Hussein’s security militias.

The Taguba Inquiry confirmed independent reports that U.S. soldiers had raped women prisoners. Some of them were forced to bare their breasts for the camera. The women detainees sent messages to the resistance, pleading with them to bomb and destroy the prison and obliterate their shame and suffering. As far back as November, 2003, word was getting out. Earlier this year, The Guardian reported a woman prisoner pleading, “We have daughters and husbands. For God’s sake don’t tell anyone about this.” Another Iraqi prisoner, a male, was more forthright: “We need electricity in our homes, not up the arse.” This was Western civilization at its rawest, and reprisals were inevitable.

Circulating on the streets of Baghdad is a photograph of a U.S. soldier having sex with an Iraqi woman. War as pornography. In the West, this and similar images have been suppressed. (Was it out of deference to John Ashcroft, the U.S. Attorney General, a fanatical evangelist who blushed each day when he saw the stone breasts of the gorgeous Spirit of Justice in the hallway outside his office and so had them covered?) Was the Pentagon fearful of the reaction from the world at large? And what about the women of Afghanistan, who, we were informed only a few years ago by the White House women – Hillary Clinton and Laura Bush – would be liberated by invasion and occupation? The women are still waiting, while rapes and tortures in that country go unreported.

Into this amoral terrain, the other side responded with eye-for-an-eye justice. The Iraqi resistance responded to the U.S. rapes and torture with kidnappings, car bombings targeting U.S. military and civilians alike, and, in Saudi Arabia (because, to the resistance, this war is borderless), ritualized beheadings of Western hostages. At first, the images of rape and torture trickled out (shame seemingly keeping their reproduction in check), but the opportunity to exploit these hideous transgressions was too ripe, too available, and the slow seepage became a flood. Newly equipped, local mullahs, clerics from neighbouring states, and others demanding the immediate evacuation of the “Western infidels” busily recast the short history of the war: since Gulf War I the West has been bombing Iraq; economic sanctions, not the Baathist regime, crippled its opportunity; and only we can protect the proud face of Islam against the Christian hordes. You can hear the chant: “I ask you, which civilization, Islam or the West, is collapsing?”

I was in Egypt and Lebanon when news of the Abu Ghraib torture broke. I did not meet a single person (not even among Europeans and North Americans who work there) who was surprised. Outside the U.S., the echoes of history have never ceased to resonate. The tortures in Iraq revived memories of Aden and Algeria, Vietnam, and, yes, Palestine. But what can explain the shock evinced by so many in the West when the torture was made public? One can excuse forgetting the Inquisition or the Ordeal by Fire or the heresy-hunters of Christianity who tortured and killed Cathars and Albigensians, or, later, the majestic polemic by Voltaire against the cruelty of torture. But have the citizens of North America forgotten what happened in South and Central America, Asia, and Africa less than fifty years ago? When dead Iraqis are not even counted, why the surprise that the live ones are mistreated? To understand this collective amnesia we must, against the strongest impulses of a U.S. Administration intoxicated by the future, straddle the present while stepping back in time.

On June 8, 2004, The Financial Times reported that U.S. lawyers said, “American interrogators can legally violate a U.S. ban on the use of torture abroad,” and “legal statutes against torture could not override Mr. Bush’s inherent powers.” From leaked Administration documents, it is now clear that the U.S. justification for torture at Abu Ghraib (and at Guantanamo Bay) was predicated on the notion that Al-Qaeda “irregulars” do not observe, and therefore cannot be covered by, the laws of war. In the battle against these anarchic warriors – this asymmetric devil intent on destruction – the U.S. sought to circumvent not only the Geneva Conventions, but its own 1996 U.S. War Crimes Act. It is pointless to pretend that the implicated GIs were indulging in spontaneous fun. The soldiers were wrong to obey orders, but who will punish their leaders?

Collective memory loss in the West could be the result of a superiority complex. We won. We defeated the “Evil Empire.” Our culture, our civilization is infinitely more advanced than anything else, which might explain the shock waves created by the torture revelations at Abu Ghraib. One of the features of domination is that those who do not identify with it are categorized as the enemy. George W. Bush’s post-9/11 injunction, “If you’re not with us you’re with the terrorists,” was, for a while, accepted without question throughout the Western world and by elites everywhere. It was merely an adaptation of the New Testament’s “He who is not with me is against me.” The notion that he might not be against you but in favour of something more constructive was/is regarded as impermissible.

It was Carl Schmitt, a gifted legal theorist of the Third Reich, who insisted that the totality of politics was encompassed by the essential categories of “friend” and “enemy.” This view suited most empires and Schmitt’s writings were influential in the United States after the Second World War. Conservative thinkers such as Leo Strauss acknowledged his influence. The message – studied, learned, and adopted by the “Straussians” now surrounding President Bush – was straightforward: if your country does not serve the interests of our empire it is an enemy state. It must be occupied, its leaders removed and more pliant satraps placed on the throne. In time, they hoped, the presence of a Roman legion would become unnecessary. However, soon after the legion withdraws, the satrapy begins to crumble. Occupation, withdrawal, rebellion, another occupation, and, sometimes, self-emancipation, is a pattern in world history.

To justify their excesses, imperial regimes require intellectual legitimizers, and, in the U.S., the torch was passed from Leo Strauss and the Chicago School to Samuel Huntington and Francis Fukuyama. Huntington was a senior counter-insurgency expert in the Johnson administration at the time of the Vietnam War. His fertile imagination contributed to the scheme of “strategic hamlets,” after studying the insurgent texts of the enemy – Mao Zedong, Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, Vo Nguyen Giap – on guerrilla warfare in which all four practitioners explained that success was impossible without the support of the population. Failing to understand what motivated the guerrilla fighters or the causes of the war, and believing the main problem was the links of the resistance to the people (“fish in water,” according to Mao), Huntington conceived of separating the two. The scheme envisaged herding poor peasants into “strategic hamlets,” which were glorified rural concentration camps surrounded by barbed wire and guarded day and night by soldiers. The U.S. military decided to give it a try. What Huntington and his superiors had failed to grasp was that many of “the people” were, in fact, members or supporters of the Vietnamese resistance. Soon they began to organize inside the “strategic hamlets.” The weaknesses of each hamlet were mapped and dispatched to the guerrillas, and the scheme came to an ignominious end.

Fukuyama did not engage in anything as dramatic, but as a State Department employee he wrote a policy paper on Pakistan during the years of General Zia’s brutal dictatorship suggesting that Pakistan turn its back on India and concentrate on its links with the Islamic world, i.e., the Gulf States and Saudi Arabia. The generals were grateful for this advice, which suited their material and strategic needs, and were very admiring of Fukuyama’s démarche. When the Berlin Wall came down, a new version of an old idea, the triumph of liberal democracy, began to agitate Fukuyama.

Then came the total collapse of the Soviet Union and the restoration of a peculiar form of gangster capitalism in that world. Did the triumph of capitalism and the defeat of an enemy ideology mean we were in a world without conflict or enemies? Both Fukuyama and Huntington produced important books as a response to the new situation. Fukuyama, obsessed with Hegel, saw liberal democracy/capitalism as the only embodiment of the “world-spirit” that now marked the “end of history,” a phrase that became the title of his book. The long war was over and the restless world-spirit could now relax and buy a condo in Miami. Fukuyama insisted that there were no longer any available alternatives to the American way of life. The philosophy, politics, and economics of the Other – each and every variety of Socialism/Marxism – had disappeared under the ocean, a submerged continent of ideas that could never rise again. The victory of capital was irreversible. It was a universal triumph.

Huntington was unconvinced, and warned against complacency. From his Harvard base, he challenged Fukuyama with a set of theses first published in Foreign Affairs (“The Clash of Civilizations?” – a phrase originally coined by Bernard Lewis, another favourite of the current administration.) Subsequently these papers became a book, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. The question mark had now disappeared. Huntington agreed that no ideological alternatives to capitalism existed, but this did not mean the “end of history.” Other antagonisms remained. “The great divisions among human-kind and the dominating source of conflict will be cultural. . . . The clash of civilizations will dominate global politics.” In particular, Huntington emphasized the continued importance of religion in the modern world, and it was this that propelled the book onto the bestseller lists after 9/11.

What did he mean by the word civilization? Early in the last century, Oswald Spengler, the German grandson of a miner, had abandoned his vocation as a teacher, turned to philosophy and history, and produced a master-text. In The Decline of the West, Spengler counter-posed culture (a word philologically tied to nature, the countryside, and peasant life) with civilization, which is urban and would become the site of industrial anarchy, dooming both capitalist and worker to a life of slavery to the machine-master. For Spengler, civilization reeked of death and destruction and imperialism. Democracy was the dictatorship of money and “money is overthrown and abolished only by blood.” The advent of “Caesarism” would drown it in “blood” and become the final episode in the history of the West. Had the Third Reich not been defeated in Europe, principally by the Red Army (the spinal cord of the Wehrmacht was broken in Stalingrad and Kursk, and the majority of the unfortunate German soldiers who perished are buried on the Russian steppes, not on the beaches of Normandy or the Ardennes), Spengler’s prediction might have come close to realization.

He was amongst the first and fiercest critics of Eurocentrism, and his vivid world view, post-modern in its intensity though not its language, can be sighted in this lyrical passage:

“I see, in a place of that empty figment of one linear history, the drama of a number of mighty cultures, each springing with primitive strength from the soil of a mother-region to which it remains firmly bound throughout its whole life-cycle; each stamping its material, its mankind, in its own image; each having its own idea, its own passions, its own life, will and feeling, its own death. Here indeed are colours, lights, movements, that no intellectual eye has yet discovered. Here the Cultures, peoples, languages, truths, gods, landscapes bloom and age as the oaks and stonepines, the blossoms, twigs and leaves. Each Culture has its own new possibilities of self-expression, which arise, ripen, decay and never return.. .”

In contrast to this, he argued, lay the destructive cycle of civilization:

“Civilizations are the most external and artificial states of which a species of developed humanity is capable. They are a conclusion, death following life, rigidity following expansion, intellectual age and the stone-built petrifying world city following mother-earth . . . they are an end, irrevocable, yet by inward necessity reached again and again. . . . Imperialism is civilization unadulterated. In this phenomenal form the destiny of the West is now irrevocably set. . . . Expansionism is a doom, something daemonic and intense, which grips, forces into service and uses up the late humanity of the world-city stage.”

Three-quarters of a century later, Huntington returned to Spenglerian themes but inverted their message. He amalgamated culture and civilization. For him a civilization is a meta-culture, “the highest cultural grouping of people and the broadest level of cultural identity people have short of that which distinguishes humans from other species.” Huntington’s chart of the top eight cultures/civilizations consists of Western, Sinic/Confucian, Japanese, Islamic, Hindu, Slavic-orthodox, Latin American, and, reluctantly, African. (The reluctance is due to an inner voice that injects doubt as to whether Africa really qualifies as a civilization.) And religion is “perhaps the central force that motivates and mobilizes people.” The gulf is between “the West and the Rest.” The West is the only civilization that defends freedom, democracy, and the free market, while the rest resist Western efforts to advance these noble values. The West is at the height of its power and, argues Huntington, utilizes the United Nations and the International Monetary Fund to impose its will globally. He discards the notion of a real difference between unilateralism and multilateralism because “the very phrase the ‘world community’ has become the euphemistic collective noun to give global legitimacy to actions reflecting the interests of the United States and other Western powers.” He is correct on this, if not on religion.

I do not believe that faith is the main determinant of global mass mobilizations. It plays a part, the extent of which is variable. The West is certainly divided on this: Europe is not deeply religious, whereas in the U.S., the situation is frightening. According to the latest surveys, 95 percent of Americans believe in God, including 91 percent of those who define themselves as liberals. (Only 70 percent believe in angels. This always disturbs me. I wish the angels had the majority since it would provide belief with a slightly surreal edge. More satisfying is a recent Gallup briefing [February 25, 2003] that reveals a bipartisan belief in the horned one: the Democrats are so pious that 67 percent of them actually believe in the Devil, only 12 percentage points below the Republicans. Why more satisfying? “Who believes in the Devil,” wrote Thomas Mann in Doctor Faustus, “already belongs to him.”) Neither in China nor Russia does religion play a similar role, and I’m convinced there are more unbelievers in the house of Islam than can ever be counted in public, but this is a theme to which I shall return below.

In Huntington’s world, the most dangerous combination would be the unity of Confucian and Islamic civilizations, neither of which shares the West’s attachment to human rights. And both of which, he might have added, could hold the West to ransom. (Wary of China, the U.S. is pushing to open it up for business, and hoping that the steamroller of American culture and product-selling will take hold. Masses, it is hoped, will be satiated by shopping.) The U.S. global strategy necessitates control of the world’s oil reserves, while domestically its economy is heavily dependent on cheap imports from China.

Soon after Huntington’s book appeared others joined the fray and stressed the importance of cultural differences in understanding politics, economics, demography, etc. Much of this was side-lined after 9/11 focused the debate on the “threat of radical Islam” and the “war against terror.” Instead of the West against the Rest, the new turn made it the Rest versus Islam. Huntington, to his credit, was not tempted by the neo-conservative arguments dominating White House ideology before the debacle in Iraq. He modified his own views and argued that it was a clash within Islam that was the main problem and not one of civilizations, which was not the case either, but certainly made one wonder how this could be squared with his view that “faith and family, blood and belief, are what people identify with and what they will fight and die for.”

And what is this Islam, this new bogeyman used to frighten the children? The very idea of Islam as an institutional matrix that organizes terror and resistance to the West throughout the globe is a travesty of past and present. For most of the 20th century, organized or political Islam was, more often than not, supportive of the British Empire, and later, its American successor. It was a conservative social force, rattling the chains of superstition and fanaticism to stifle even the most fragile tremors of radical revolution. Throughout the Cold War, the Wahhabi preachers of Saudi Arabia (currently viewed as Enemy No.1) were dispatched across the Muslim world to preach the virtues of religion and counter-revolution, and where divine truth would not prevail over reason, there were always purses pregnant with petro-dollars to help win new recruits. Where neither worked, the U.S. organized a military coup. One such case was Indonesia.

At college in Pakistan during the early Sixties, Muslim socialists like me were in a permanent debate with the Islamists, who would declare that religion and the state were indivisible because “Islam is a complete code of life.” We used to laugh when we heard this sentence and often preempt them by mouthing it ourselves in parrot fashion. Sometimes, when debates became heated, we would ask: “Which is the largest Muslim country in the world?” Back would come the reply. “Indonesia!” Another question would be hurled back by our side: “Which is the largest Communist Party in the non-communist world?” Silence. We would chant in unison: “The Communist Party of Indonesia.” These youthful exchanges were not pure banter. We were arguing that it was perfectly possible to be part of Muslim culture, appreciate its finer points, without being a believer. The Indonesian Left (more than a million and a half strong) was wiped out in 1965 by General Suharto. It was one of the worst massacres of the Cold War, fully backed by the U.S. The vacuum in Indonesia created by the massacres of thirty-nine years ago left the field clear for the Army and the Islamists. The same pattern, if not on the same scale, occurred elsewhere.

I remember well the mood that gripped Pakistan during 1969–70. A three-month-long rebellion against a pro-U.S. military dictator by students, workers, and peasants had triggered a societal upsurge. Lawyers took to the streets one day, prostitutes the next. The dictatorship crumbled and the country’s first ever general election took place. Throughout the campaign the secular, socialist currents dominated politics. The religious groups were totally marginalized and often resorted to violence. As a visiting academic, when I arrived in Multan to address a rally of nearly fifty thousand workers and peasants, the student wing of the Jamaat-i-Islami physically attacked the group of students who had come to meet me at the airport and escort me to the meeting. They stoned us as the police stood by and watched. This was a common occurrence in those days, but the intimidation didn’t work.

The 1970 Pakistani elections saw the Islamists wiped out as a political force. When, in 1972, Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was addressing a rally in Lahore, a group of mullahs started abusing him. Bhutto, who often spoke at several meetings a day, had an attendant who carried a tiny whisky flask and when the prime-ministerial voice became too hoarse, a glass containing amber liquid would appear and relieve the prime minister’s exhaustion. At the Lahore rally there were half a million people present as well as diplomats, foreign journalists, etc. As Bhutto sipped from the glass, a bearded man stood up, pointed at him, and shouted: “Look, people. See what he is drinking.” Bhutto, who loved repartee, held up the glass and declared, “Yes, look. It’s sherbet.” The crowd roared with laughter. The well-placed mullahs stood up in different places and replied: “It’s sharab (alcohol).” Finally Bhutto lost his temper and shouted: “Fine. Yes, you motherfuckers, it is sharab. Unlike you, I don’t drink the blood of the people.” The crowd was ecstatic. A spontaneous chant arose and rent the air: “Long may our Bhutto live! Long may our Bhutto drink!”

Times are different now, but not just in the Islamic world. I emphasize these very different events in Indonesia and Pakistan to show that the two largest Muslim states were subjected to the same political storms and influences as the non-Muslim world. I am no apologist for radical Islam, the widespread corruption of Islamic kingdoms, the atavistic mullahs and Qur’anic literalists, the utter venality of the House of Saud, etc. But if Muslim civilization has become a spent force (see Bernard Lewis’s What Went Wrong? Western Impact and Middle Eastern Response) in need of top-down reform, one must eschew political agendas and deconstruct what actually happened. We require a social vision that transcends religious conservatism in the Islamic world, and the American model simply will not work. It has proven itself an unviable alternative. In Indonesia and Pakistan there was an internal dynamism demanding reform. Those deemed “Communists” or “Socialists” by successive U.S. administrations were, in fact, moderates committed to democratization. These were the reformers in need of foreign support. Over and over again, U.S. Cold War myopia resulted in backing the wrong side. Today, in the Middle East there will be no transformation until the West answers the simple questions being asked on the street: Why Iraq and not Saudi Arabia? Why blanket support for Israel and blindness to Palestinian suffering?

This is why I reject the civilizational theses of Huntington and Islamist ideologues who also believe that the difference of religion and blood is the determining divide in the modern world. And I reject the deracinated house Muslims in the North American and European diasporas, so desperate to please, so eager to be integrated – and on any basis – that they sink to their knees and join the sickly chorus, winning the earthly rewards of media attention and tenure. At the top of this heap lies Ahmed Chalabi, the Iraqi handmaiden to the White House operatives.

A point repeatedly made by professors of human rights on U.S. campuses and “civil society” groups to justify Western interventions, including the invasion and occupation of Iraq, is that it is democracy and the plurality of institutions independent of the state, but rooted in capitalism, that define the culture of the West. In 1919, an anti-imperialist wind arose in Afghanistan and the tribal confederacy accepted Amanullah as the king. He was a modernizer and admirer of Kemal Ataturk. His wife Soraya was a proto-feminist. The nationalist intellectuals in Amanullah’s circle prepared a draft constitution. It included universal adult franchise. If it had been implemented, women in Afghanistan would have obtained the vote before their sisters in Britain and the West. The reason it wasn’t implemented was that the British, via an experienced agent – T. E. Lawrence – stoked up a few tribes, paid them, and told them that women were being encouraged to become prostitutes. The British themselves then intervened to topple Amanullah.

Ironically, as the culture of democratic life deteriorates in the West, there is a growing demand for self-expression in much of the Muslim world. The citizens of Egypt and Saudi Arabia, not to mention Syria and the Gulf statelets, are desperate to choose their own governments, but there is a problem. It’s what Huntington has referred to as “the democratic paradox.” Or in plain language: democracy might produce elected governments hostile to the U.S. This is true. It might. That’s why Washington prefers the kleptocratic Saudi dynasty and the moth-eaten military regime in Egypt.

And Iraq? The appointment of Iyad Allawi, an ex-CIA agent, as the new prime minister, and the infamous Cold War hawk John Negroponte as the new U.S. ambassador, is an indication of the tortures that lie ahead for the citizens of Iraq. The demand for an elected constituent assembly (first put forward by Ayatollah Sistani) is straight out of the French Revolution. But it would probably produce a government that would unite the country on the basis of two clear-cut aims: the withdrawal of all foreign troops and Iraqi control of Iraqi oil. To have occupied a country and then watch it flout the Washington Consensus would be too painful. So puppets are appointed and the resistance continues.

Meanwhile, in neighbouring Iran, a decrepit clerical regime is increasingly isolated from the population. Sixty-three percent of the people are under thirty years of age. All they have known is the rule of the clerics. They want something different. Despite the clerics, Iran has a vibrant semi-clandestine culture. The Iranian new-wave cinema is flourishing and, as enthusiastic exploiters of the Internet, Iran’s dissident bloggers dominate cyberspace. While the clerics continue to suppress free speech (closing down dissident newspapers such as Neshat), such reprisals are addressed in courts of law. Iran offers hope. When the clerics are defeated, the people of this country who accepted the leadership of the mullahs to get rid of the Shah might inaugurate a reformation with far-reaching effects. I would not be surprised if mosque and state were divided forever after another upheaval in Iran. In the current climate, Iranian self-emancipation would be seriously delayed or halted by foreign intervention.

In 1995, an Afghan-American ideologue, Zalmay Khalilzad (currently the proconsul in Kabul and busy negotiating deals with Taliban factions to preserve his puppet protege), published an essay in which he suggested that U.S. hegemony had to be preserved at all costs – if necessary, by force! September 11 provided the opportunity to try out the theory. For President Bush II, Ahmed Chalabi provided a perfect bookend to this history, but Iraq is proof that the use of force can provoke a mighty resistance.

Cultures and civilizations are now, and have always been, hybrids. To suggest otherwise is to fall prey to the twin devils of ideology and chauvinism. The tragedy of the abuses at Abu Ghraib is that they created a clash of civilizations where no such clash had existed. Through its own myopia, the West has given radical Islam the ammunition it was thirsting for. In the short term, President Bush will pursue re-election by insisting that his hands are clean and that the forces of darkness are behind every door. If this blindness and these lies persist, the long-term prospects are too desperate to contemplate.