phnom penh—I was climbing across the crumbling remains of Beng Melea, a one-kilometre-square temple complex built early in the twelfth century in northwestern Cambodia, and said to be the model for the layout of the Holy City of Angkor Wat. Each stone I stepped upon was part of a frieze or had a bas-relief carved into at least one of its six sides, and would fetch a minimum of several thousand dollars in a shop in Bangkok, more in Hong Kong, even more in Zurich and New York. I looked up at carved columns embraced in the branches of fig trees. Strewn on the ground were more pieces of statuary. I was only forty kilometres from the Laos border. It would be no trouble to bribe the driver of a rackety stake truck to take me across with five or more of the things.

I had, despite myself, begun to think like a looter, an art thief, a species of criminal with which Cambodia is currently rife, thanks to land-mine-clearing teams. As the land mines are removed, Cambodian art treasures are increasingly accessible. They are also extremely valuable in the antiquities market, because so little has been available over the last forty years.

The main entrance to Beng Melea is “guarded” by one jovial, unarmed young man, who sits at a deal table under a silky oak tree. My thoughts were interrupted by a shout from the sixteen-year-old kid, a local villager, who was guiding me: “Land mine!” He pointed to the red slash on the slender branch of a young tree, a warning that a land mine was buried at the roots, one that is in too precarious a position for the Cambodian Army to try and dig up.

Platoon Thirty-Seven, Unit Six of the Cambodian Mines Action Centre (cmac), had been here recently. Members of the platoon had cleared the central areas of the compound, giving worshippers and visitors access once again to the main area of the site, which includes temples, courts, and libraries. But there are still mines buried under stones and at the feet of trees around the perimeter of Beng Melea.

Over the past ten years, cmac and a few non-governmental agencies have been clearing the country of mines and unexploded ordnance, but it is a task that will probably never end. The United States dropped more than half a million tons of bombs on Cambodia between 1969 and 1973. Then came the Vietnamese with Chinese-manufactured land mines. Between 1975 and 1979, the Khmer Rouge planted mines unceasingly, after the dictator Pol Pot ordered all of Cambodia’s land borders – with Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam – to be mined to keep out invaders. There were four sides in the fourteen-year civil war that followed the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge in 1979 and each of them used land mines. Khmer Rouge veterans were still laying mines in the late 1990s. Cambodia has more amputees per capita than any other country in the world.

To the peasants of Cambodia, the de-mining teams are heroes, protecting lives and opening the terrain for the first time in decades to settlement and development.

Travelling the route of recently cleared land, you see tiny villages that have sprung up like flowers after the first rain in a parched land. And every now and again, the deminers enrich Cambodian heritage in another way, by unearthing priceless art. In 2003, a crew clearing a trail near the village of Chrey Krem in the Pursat Province found two ornate temple bells that date back to around 200 BC.

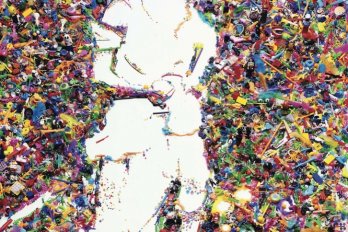

Following closely behind the demining teams, however, is something that doesn’t herald hope and rebirth but, rather, destruction and loss: those who plunder the now accessible temples and pagodas for profit. Some of these are peasants who legally salvage UXO metal for a few riels. Others are sophisticated thieves who are part of complex international operations. Because there are thousands of temples and pagodas, towers, steles, and pyramids throughout the county, and there is not enough money to guard more than a fraction of them, the art is there for the picking. Work that can’t be simply hauled away has been attacked with picks, chisels, chainsaws, and pneumatic drills.

Even Angkor Wat, the most popular tourist attraction in South East Asia and of inestimable value to the Cambodian economy, cannot be adequately guarded, not even by French Foreign Legion-trained Heritage Police.

Tamara Teneishvili, a program specialist with unesco in Phnom Penh, sighs at the enormity of the problem: “The art is so accessible and there is so much corruption.”

In March, 2003, she says, a half-metre-tall head of Vishnu was stolen from the stone banks of the Kbal Spean River. “Thieves just went in one night with a chainsaw and cut it out.” It’s now well protected “with armed guards,” she says, but when I take the three-kilometre hike along a steep trail through a chiarascuro forest of walnut and lichee trees to get to the main carvings along the river, I discover the entire stretch of the Kbal Spean from the its source above a waterfall to the plains below is guarded not by automatic-weapon-toting guards but by one unarmed kid in overalls and flip flops who says he’s twenty but looks fifteen.

Banteay Srey, thirty kilometres from Siem Reap, is a late-tenth-century Hindu temple built of pink sandstone. It is also the site of the most notorious South East Asia art theft, by André Malraux in 1923. Then minister of culture for France, later an author and resistance hero, Malraux used a chainsaw to get his treasure: two stones with bas-relief of dancing girls. Malraux was arrested at Phnom Penh for possessing stolen antiquities and given a suspended sentence. He returned to France but later returned to Indo-China to campaign against colonial exploitation.

Today, says Teneishvili, “the shipment of these big pieces out of the country can only be accomplished with the collusion of the military. The collectors claim they are helping to preserve Cambodia’s heritage.” It is believed that diplomats, who can use their immunity to facilitate art theft, are also involved.

But wealthy collectors who are seeking the grandest pieces aren’t the only problem. Smaller works command prices from $5,000 to $250,000 (U.S.), and require no contact with the military or diplomatic corps since they are much easier to spirit out of the country – either disguised as or hidden in a batch of similar-looking but legally purchased pieces. Most border guards are not art experts. One need only pay a visit to the workshops of Preah Ang Makhak Vann Street in Central Phnom Penh and purchase, for instance, five bas-reliefs of celestial dancing girls and place your stolen dancing girl among them. Moulds can be purchased in these workshops and the art work hidden inside. Or you can cover your stolen piece with a removable adhesive acrylic that holds paint, plaster, cement, or modelling paste, with which you can make your own carving of Vishnu or sacred elephant.

But the usual way is still to invade a site after it has been demined, and spirit your treasure over the border. When I was with Platoon 37, in the jungle, I asked if they ran into looters. Colonel Mean Sarun shook his head sadly. “Is the Army spread too thin?” I pressed. The unit’s medic, who was standing with the colonel, answered my questions this way, “I’ve been shooting at people since I was sixteen years old, during the Civil War. Many of the others here are older than me” – he gestured toward the colonel – “and have been shooting at people even longer. We’re tired of shooting at people.”