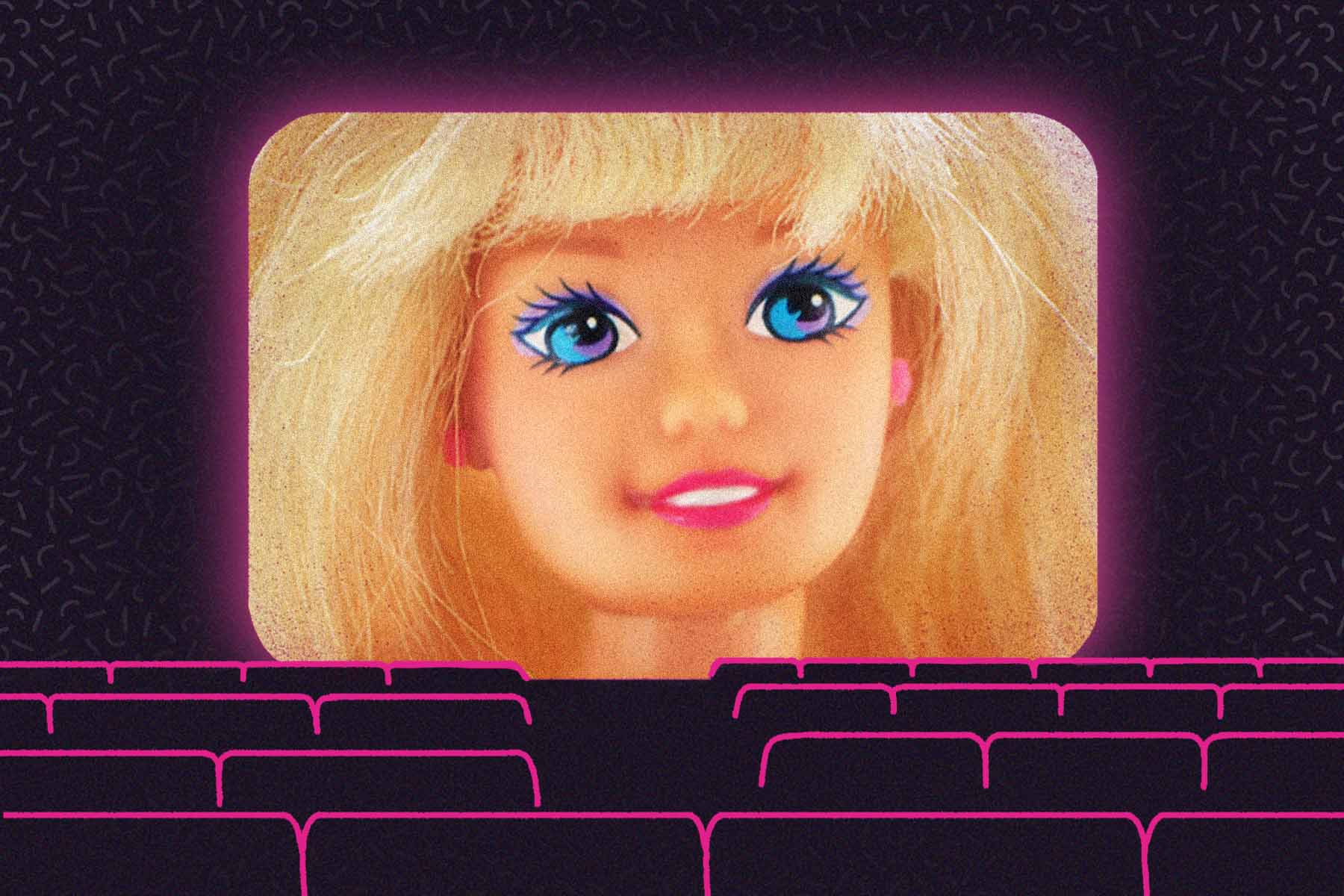

Do you have Barbie fever? Symptoms include a sudden desire to go rollerblading, a new appreciation for fuchsia, and an overwhelming urge to see Barbie, the star-studded, big-budget, hot-pink summer blockbuster.

Even if you’re immune to Barbie, you can’t ignore it. The movie, directed and co-written by Greta Gerwig and starring Margot Robbie (who also served as producer) as well as Canadian dreamboat Ryan Gosling as her boytoy, Ken, has been inescapable ever since the first trailer was released in December: a brief homage to 2001: A Space Odyssey but with Barbie as the monolith. Since then, Barbie has been everywhere: she’s in Vogue, all over social media (thanks to the official Barbie Selfie Generator), even being used in insurance ads. The simultaneous release of Oppenheimer, a sombre biopic about the creator of the atomic bomb, has given rise to a bizarro crossover genre called Barbenheimer, a term which yields more than 2,700 results on Etsy. If you’re experiencing Barbie fatigue, good news: there are Barbie-branded multivitamins to keep your energy up.

Yes, people should just be allowed to enjoy things. But the unabashed, wholehearted enthusiasm for Barbie is surprising, particularly from the cynical, anti-capitalist league of millennials and Gen Zers. Why, I wonder, are people so excited for a two-hour toy commercial for adults?

You can make a feminist argument for Barbie: it’s a rare, big-budget studio picture made for a female audience. Its $100 million (US) budget is more than twice that of Magic Mike’s Last Dance, the last splashy cinematic offering at the altar of female wish fulfillment (though it’s half of what Netflix spent on Gosling’s 2022 action film, The Gray Man, a movie that no one I know has watched). While it’s nice to be acknowledged by Hollywood as a broad demographic, Barbie exemplifies the problem of conflating any product targeted to women as inherently feminist. In reality, she has always appeared only as feminist as she needs to be. The 2016 line that introduced diverse body types as well as new hair textures and skin tones was reportedly made in response to declining sales. Like other products aimed at a female audience, Barbie embraces a kind of non-threatening, feel-good iteration of feminism dictated by market logic: never so radical as to be alienating to consumers but just enough so they can imagine that enjoying the doll (or watching the movie) is an empowering act. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with liking Barbie or playing with Barbie; she’s a toy, not a manifesto.

What is the Barbie movie about? No one knows and, crucially, no one cares. Gerwig has cast a secretive, mystical shroud over the film: in an interview with Vogue, Robbie said that in lieu of providing the studio with a detailed film treatment, Gerwig sent an abstract poem about Barbie. The barest hint of a plot has been revealed: Barbie goes on some kind of hero’s journey into the Real World, and at one point, she and Ken go rollerblading. The casting of Barbie is a sly bit of genius: Robbie is both sublimely beautiful and surprisingly generic, with at least five doppelgangers in Hollywood, one of whom—the French British actress Emma Mackey—is also playing a Barbie in Barbie. (There are fifteen actors playing Barbies in the movie and seven playing Kens.) When she read the script, Robbie told Vogue, she said to her husband, “It is such a shame that we’re never going to be able to make this movie.”

But Mattel, the toy company that first started selling Barbies in 1959, did let them make it, perhaps because it understands that what many grown-ups remember most fondly about Barbie is not her wholesomeness but their pleasure in subverting it. As one viral tweet put it, “If the Barbie movie doesn’t have a scissoring scene it will be completely inaccurate.” (Barbie porn is, incidentally, more popular than ever, according to Rolling Stone.) Keeping the details of the film conspicuously vague while teasing out the possibility of raunch is a strong draw for audiences curious to find out if the movie—with its PG-13 rating—will reflect their own playful relationship with the doll, and it allows our imaginations to run wild with anticipation.

The real appeal of the movie might not be the movie at all. In 1962, Mattel co-founder Elliot Handler explained his sales strategy to Time magazine as “the razor and razor blade”: Barbie is the razor and the blades are her endless accessories, which beget more purchases. The more you buy, the more you feel compelled to buy. When a fierce debate erupted on social media in May over whether Barbie was a toy for rich kids, both sides had a point. A single doll might be affordable but building her a perfect bubble-gum paradise is costly—and aren’t those perfect details the whole point? What is a Barbie without her accessories? Gerwig’s meticulously detailed Barbie Land set, which supposedly caused a global shortage of a particular shade of neon-pink paint, suggests an answer.

With Barbie, Mattel has made adults themselves the sales target. The movie is being sold squarely to nostalgic millennials and Gen Zers through a clever ploy of more than 100 brand collaborations to adorn your own personal Barbie Land: there are Barbie-branded shoes (from stilettos to Crocs), jewellery, hair clips, rollerskates, crop tops, scented candles, cowboy hats, frozen yogurt, luggage, gaming consoles, electric toothbrushes, rugs, doughnuts, notebooks, pool floaties, sugar-free lemonade, and even a Barbie DreamHouse on Airbnb. If it can be manufactured in pink, it can be barbied.

While it may seem scattershot, this broad branding is likely deeply controlled. In 1997, Mattel unsuccessfully attempted to sue the band Aqua for trademark infringement over their song “Barbie Girl” (“Life in plastic, it’s fantastic / You can brush my hair, undress me everywhere”), claiming it tarnished Barbie’s reputation. Of course, though, a sample of the song will feature in the new movie.

The term for this proliferation of movie-themed merchandise is “toyetic,” conceived by toy company executive Bernard Loomis, who came up with the idea of the Hot Wheels TV show in 1969 to boost sales of the toy cars. In the 1970s, he launched a line of toys based on the Star Wars franchise. Any parent who has walked through a drugstore with their child and ended up reluctantly purchasing a Frozen toothbrush understands how effective this strategy is. But, with Barbie, Mattel is betting that adults have the same impulse control as toddlers. More than a dozen live-action films based on Mattel toys—from American Girl dolls to the Magic 8 Ball—are in the works, with Barbie at the vanguard of the Mattel Cinematic Universe. It’s hard, though, to imagine people clamouring as fiercely for Barney or Uno-branded merchandise.

Barbie represents the first toyetic property aimed directly at adult women. But it also represents the creep of streaming TV’s appetite for mindless content, from the home to the theatre. In 2020, writer Kyle Chayka coined the term “ambient TV” to describe this type of vacuous entertainment: “there is nothing to figure out; as prestige [television] passes its peak, we’re moving into the ambient era, which succumbs to, rather than competes with, your phone.” Barbie feels like the debut of ambient cinema: less a film than a mood, a vibe, and an aesthetic, a soundtrack and a selfie backdrop.

The storyline of the movie is almost beside the point, which makes it the ideal film for a moment in time when narrative complexity is yielding, in all mediums, to explicitly branded, or merely ad-friendly, content. In a telling memo to staff announcing the end of BuzzFeed News, CEO Jonah Peretti summarized BuzzFeed’s ongoing objective as empowering editorial staff to “do the very best creative work and build an interface where that work can be packaged and brought to advertisers more effectively.”

Storytelling is just a vessel for marketing, and in that regard, the towering scale and transparent ambition of Barbie—to boost Mattel sales—comes as a kind of relief. If everything is just content now, at least this content promises to be fun. You can’t outrun the pink tsunami, so why fight it?