A decade ago, the advent of Instagram fundamentally restructured how we see celebrity. Ordinary people, by becoming their own paparazzi, were able to attain a level of fame once reserved for the world’s biggest stars. Among them were the influencers, those eminently visible people who began to profit off their cultural capital and ally themselves with brands in order to promote products on their various platforms.

An influencer’s persuasiveness depends on the feeling of proximity and intimacy they’re able to develop with their followers. It’s an easy accessibility—they’re forever just a tweet away, just a like away. In willing themselves closer to us, they’ve abolished the once seemingly impenetrable wall between stars and their fans. In French, the word for “close,” proche, is etymologically linked to the word for next, prochain. As if the next person to speak about lipstick in front of a camera might be me. When I watch these YouTube videos, in some sense I’m dreaming up a future for myself.

The era of the tabloids—where we once used to encounter un-made-up stars, crying, drunk, or unbalanced, shuffled off the stages of their own lives; where we used to laugh at the spectacle of their downfalls; where the goal was to capture their worst moments—is over. By contrast, journalist Amanda Hess has suggested, Instagram is defined by an aesthetic of control. Influencers’ lives take place in an entirely different reality, one where the images people have of one another are masterfully manipulated. Even their most vulnerable moments are as staged as movie shoots. Social media allows us—and encourages us—to surveil and monitor the body and its extensions. Whether we’re sharing a picture of some washed-up driftwood or of a perfectly made-up face, we are always the ones deciding how much of ourselves to show off to others.

Influencers exert a gravitational pull similar to that of reality TV stars. They’re just a multiplatform version, a Pokémon evolution. By responding to the dictates of authenticity, they permit us to develop a much more personal feeling of belonging toward the products we consume.

It’s a mode of engagement that contrasts starkly with the general air of distrust that people hold toward faceless multinational corporations. Their slick, impersonal surfaces represent the polar opposite of the pore-and-scar-covered skin I associate with my own. Authenticity, by contrast, rings of imperfection, of all that can be hurt or sickened, of that which bears the marks of aging, the imprints of life’s hard knocks. In fact, we tend to think of authenticity in terms of the self—we judge others by how close or how far they seem from us, from the personal crosses we bear. Corporations, by contrast, seem essentially invulnerable. I tend to think of them as invincible, inhuman. They stand like colossi, legs disappearing into the sky, antlers of smoke, grimaces of steel.

The language of business is riddled with conceptual metaphors that compare the economy to a machine. Economists write that it’s “starting up again” or else “overheating” or “idling,” like an engine. Or you hear talk of “liquidity,” of “diluting shares,” of “freezing funds,” as if finance were water being pumped through the veins of the economy. All these words do is cleverly conceal the presence of the human body—that is, they erase the flesh-and-blood workers whose actions and decisions have a direct impact on the economy. As Pier-Pascale Boulanger writes, “The truth is, there is no machine or motor—just agents who exist within power relations pursuing their material interests.”

Turning the financial sector into a nonhuman object benefits neoliberal ideology by making us believe in an economic system that could function without human involvement—almost a force of nature, like a river cascading over rocks. While this vocabulary has managed to detach economics from the human, it has also allowed large corporations to, in the collective imagination, become untethered from the human body, from its wounds and weaknesses.

Now, without a tint of humanity, corporations have lost their powers of attraction, of persuasion. They are no longer relatable—they’re not your friend. Rather, arrayed in convoluted forms, in shapeless and gigantic masses, today’s companies tend to look more like LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, a firm with a portfolio that comprises over seventy different prestige brands. In order to graft a face back onto their metal hides, the colossi, naturally, turned to influencers.

In the world of influencers, purchasing a product is seen as a special gesture, both unifying and intimate. You’re not just buying a product; you’re buying a flesh-and-blood person, the gift of their presence. And you’ll keep buying as long as the emotional bond holds, because the love we have for other people is limitless while the love we have for things can never be reciprocated. When you come to see someone as a friend, you don’t just want to support them—you also want to enter into the communities they support, to integrate into their family. Makeup gurus never fail to remind us of that fact: they each have their own mantras to repeat, from Jeffree Star’s “Hi, how are ya?” to “It’s your girl, Jackie Aina!” to James Charles’s “Hi, sisters!”—the latter going so far as to trademark that sisterhood through his clothing line, Sisters Apparel.

But taking advantage of the bonds of sorority to sell products is hardly a new strategy. By the end of the nineteenth century, cosmetics companies were pulling the very same trick, tapping into the semantic web of the family to approach their customers as sisters or friends. One such entrepreneur of the period, Madame Yale, claimed she’d been entrusted with a sacred mission: she wasn’t out to sell to customers, she was sharing with her “sisters in misery” a miracle product she herself had invented, a remedy for dull skin and sunken cheeks no doctor had been able to treat. In her brochures, Yale encouraged her customers to open up to her. Tell me all, everything, she entreated them—your aches and pains, your little victories, your dark and lonely thoughts. This clever spin on mail ordering took the form of an exchange of much more intimate letters over a century ago—but that very call-and-response behaviour is popular in today’s influence industry as well. It’s noticeable especially in influencers’ calls to action, those systematic solicitations of engagement that occur at the end of every video, when they slip in that familiar Y’all will tell me what you think in the comments.

At the turn of the twentieth century, beauty entrepreneurs—like Madam C. J. Walker, an African American woman who was the first female self-made millionaire in the United States—had to work on the fringes of retail because race- and gender-based barriers made access to traditional distribution networks, or entry into supermarkets typically stocked with white- and male-run brands, near impossible. Instead, Walker had to go door to door—but it was in doing this that she first developed the relationship-based marketing techniques that would pave the way for a genuine cosmetics empire, one that saw her become not just a businesswoman but also a political activist and philanthropist. She made community the keystone of her financial success, spinning a web of flesh and conversation to hold close the women she sold her products to and training thousands more door-to-door saleswomen like her, enabling many of them to achieve financial independence.

What many similar female entrepreneurs from the turn of the twentieth century teach us is that the then fledgling cosmetics market was one of the first sectors to take advantage of sales techniques based on social ties, advice from “friends,” mutual support, and care. I can’t help but see, in the figure of someone like Walker, a kind of protoinfluencer. Since they were able to give an emotional and social dimension to the sale of goods—to deliver not just products but advice and testimonials too—these visitors were seen as peers rather than as saleswomen. Like Tati, Jackie Aina, or Makeup Kristi, who visit us in the comfort and privacy of our personal screens, the travelling saleswoman would meet her customers where they were: confined to their homes. She was a conduit between human consumers and faceless businesses, those metal colossi. You could talk to her about your pimples, your sunken cheeks, or your hair problems, and in return, she made you feel—regardless of whether it was true—like she genuinely wanted to take care of you.

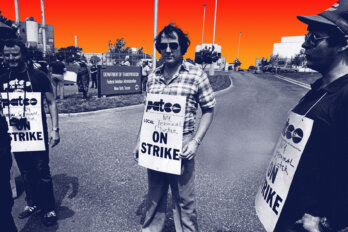

Today, the work that influencers do is often belittled or not recognized as work at all. There’s a certain logic to that: the fruits of their labour are often invisible. The primary product of an influencer is emotions, so the impact of influence—feminized and disregarded as it so often is—can be difficult to pin down.

Unsurprisingly, the vagueness inherent in such a new sector of the economy makes for increasingly precarious work, with people often operating without the benefit of any real job security. Of course, many of them are hardly to be pitied: the standard image of the influencer raking in astronomical sums of money isn’t a complete fiction. But not every influencer is Kylie Jenner. Because some are only microinfluencers or even nanoinfluencers (those with fewer than 5,000 followers), it’s easy to see how less privileged influencers might end up being taken advantage of, particularly in an industry where there is neither consensus nor transparency when it comes to earnings. But, if the lifestyle that the top influencers luxuriate in is enviable and often lucrative, it’s rendered more fragile by the threat of scandal, a single instance of which can mean the loss of tens of thousands of subscribers.

The unstable nature of influence work is also tied to the fact that it’s necessarily embedded within private platforms like Instagram and Twitter. Influencers are forever at the mercy of external factors; their successes and failures depend on algorithms and technologies that can change in a blink. You might say that their careers are part of what sociologist Zygmunt Bauman calls our “liquid modernity”—a slippery reality that changes shape when the slightest external force is applied. It spills, flows, spurts all over the ground—just like the kind of relationship the sugar daddies want: no strings attached. They want babies who get wet for money, but no waterworks, please.

The emotional relationship between influencers and influencees is also one that’s constantly threatening to break off. While any intimate relationship can sour in a heartbeat, these ones in particular revolve primarily around the sense of trust that influencers instill in their adoring publics. As a result, what people most often criticize influencers for is a lack of authenticity—the same sense of authenticity that once drew us right to them. When scandals do break, then, it’s this quality in particular that must be singled out and scrutinized. It’s common for influencers and their followers to go digging in their rivals’ digital closets, searching for old racist tweets or other incriminating statements.

These archaeological finds become weapons in a war of image, used to smear their enemies with shame and instill distrust. Faced with the incoherent jumble of shards of identity—fragments that don’t remotely correspond to the perfect public image of the makeup guru they used to love—the disillusioned fans must now face the facts instead: the person in their screens was a stranger all along.

Adapted with permission from Made-Up: A True Story of Beauty Culture under Late Capitalism by Daphné B, translated by Alex Manley © 2021. All rights reserved. Published by Coach House Books.