Ilower my head and pretend to pray. The sun is scorching the back of my neck, and my pale Irish-stock skin is pinking rapidly. Around me, the crowd has stopped all talk of cousins promoted, uncles dead, or aunts shifted to care facilities. The chatting is done for now, and we’re getting down to the business of worship. The padre, wearing a sombre black suit slashed by a kelly green sash, is reciting the Lord’s Prayer over a microphone. His voice carries traces of a brogue; his hair is white and fluffy, his eyes a snappy blue.

Behind him, a 30-ton chunk of black granite sits inside a wrought iron fence that’s worked into a shamrock pattern. Today the fence is festooned with orange, green, and white fabric—the colours of the Irish flag. The rock and the padre are in the middle of four lanes of busy traffic leading onto the Victoria Bridge in Point Saint Charles, Montreal. Behind the rock, looming over the padre’s right shoulder, I see a billboard for Fujitsu that reads, Du pas de sexe de l’été. It is the only French I see or hear.

On Intercultural Co-operation

From the website of the Réseau de Résistance du Québécois, March 6, 2008

Dennis Chow

The resistance network of the québécois has organized to distribute brochures at the St. Patrick’s Day Parade, celebration of the Irish, next Sunday the 16th of March in Montreal.

It will be a chance… to make known that we will never allow English to supplant French in Montreal, making French disappear, as Gaelic did from Ireland.

It will also be our chance to salute our ‘green-blooded’ compatriots who have chosen to make French their language… and who stand by us in our struggle for a free Québec.

long live the friendship between the québécois and the irish!

long live the free quÉbÉc!

tiocfaidh ar lÀ! (Our day will come)

My friend Denis is beside me, mumbling fervently. He’s wearing his signature white sweatshirt emblazoned with the names of Montreal’s dead and dying Irish neighbourhoods. Standing off to the side, head bowed over his white-gloved hands, is my neighbour Tony, who is leading the Legion colour guard, and praying along in full spate with about 150 other people in the middle of the road. Most eyes are closed, most heads are bowed, and everyone knows the words. Cars whip past. The curious stare. We ignore them. We are thinking about the 6,000 Irish buried beneath the asphalt at our feet.

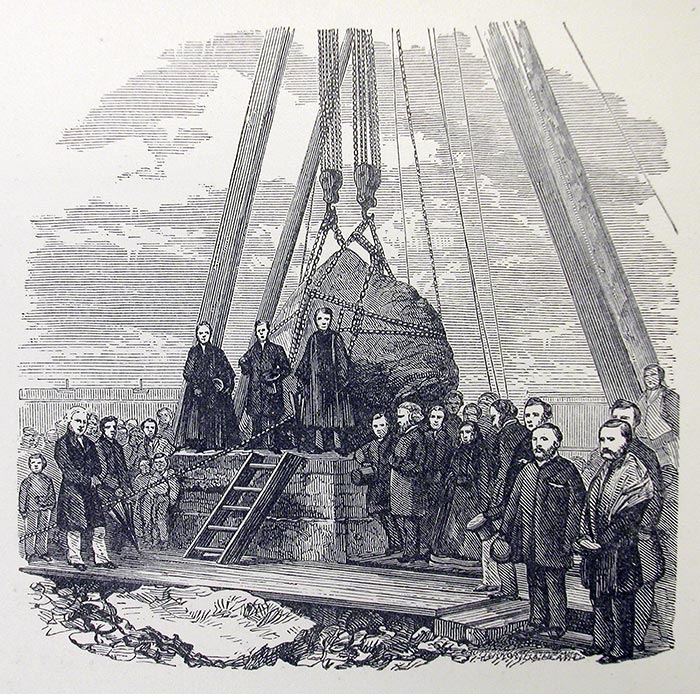

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the Black Rock memorial, a century and a half since the stone was dredged from the St. Lawrence River by men building the Victoria Bridge. The Irish community has gathered for a walk to the Black Rock on the last Sunday of May since the 1880s. They gather in memory of the Irish who were evicted from their homes by their aristocratic landlords during the potato famine, lured by the promise of payment onto ships bound for Canada, endured a three- to six-month passage in fetid cargo holds, contracted typhus, were dumped in what was then called Goose Village, died, and were buried en masse and unmarked right where we stand.

Besides, it’s an opportunity to show some fighting Irish pride.

Point Saint Charles is one of Montreal’s oldest, poorest, and most stubbornly anglophone neighbourhoods. Most of the Point’s 13,210 residents can trace roots back to Ireland (as can, apparently, about 60 percent of Québécois). Their ancestors came over to dig the Lachine Canal, build the Victoria Bridge, work on the Grand Trunk Railway. Some are like Tony, who has never been to Ireland but speaks with a subtle lilt. A few months back, he asked me how I was settling in. I moved to the Point from BC two years ago. I said I was struggling with the language (I came to Montreal with no French), and he looked very puzzled. It seemed to take him a moment to realize what language I was referring to. Tony speaks no French; nor does his wife or his young daughter. Many of my neighbours refuse to learn the language either, though they and their parents and grandparents grew up in Montreal, where almost 90 percent of the population speaks French.

A chorus of amens signals the prayer’s end. We can look up and make eye contact. At the base of the rock, Victor Boyle, national president of the Ancient Order of Hibernians (all male, all Catholic, all of Irish descent), takes over the microphone. He says a group in Ireland is prodding the government into officially remembering the famine dead. Victor tells us the Irish of Montreal are ballyhooed for keeping the memory alive. We are “a beacon,” he says.

I find all this Eireann go brách somewhat disorienting. I moved here to learn French and experience a bit of the culture, yet the storefronts of my Montreal neighbourhood are peppered with leprechauns, and the girls at the local depanneur can barely get past bonjour. So it’s a small relief to me when I spot two kids from the neighbourhood’s English-language school laying a wreath at the base of the Black Rock. They aren’t speaking French but are clearly not of Irish descent. I think they may be Bengali.

Victor is thanking us and reminding everyone that a feast is waiting back at St. Gabriel’s Church, where the walk started. The whole thing has taken less than half an hour, and people are wandering away. The padre is moving toward me. I introduce myself, and he recognizes that my name is Irish. I tell him I’ve moved to Montreal from the West Coast. “Well,” says the bucktoothed fellow beside him, “you’re halfway to Ireland. Now you’re halfway home.”