The oak savannah of Ontario’s Pinery Provincial Park is humid, sunny, and still. The only visible movement comes from microbiologist Marc-André Lachance, who is sniffing a tree trunk. With his beard, shades, and Tilley hat, Lachance looks like a cross between a birder and a member of ZZ Top. His nose has picked up a distinctive tarry odour, like carbolic soap. “Aha, flux city!” he declares, then carefully scrapes a sterilized metal spatula against a slime flux—a cluster of dark sap from a wound to the bark—to get the invisible beings he is after. Lachance is hunting wild yeasts, and he’s one of best hunters in the world.

Lachance is sometimes referred to as “the OG of yeasts” by a younger generation of researchers, though his only vanity seems to be his licence plates: YEASTS, emphasis on the plural. He has spent the past forty years stalking these single-celled organisms—which are members of the fungi kingdom—from Australia to Brazil, Malaysia to Belize, researching how insects and plants interact to foster yeast habitats. Where vacationers bring skis or snorkels, Lachance carries sampling vessels, bug dope, soft tweezers for insects, hard ones for cactus spines, and the strongest drugstore reading glasses available (“like a microscope around your neck,” he explains). Modern yeast hunters also travel with permits; in an era of bioprospecting, legal conflicts over microbial ownership are rendering visible the value of the invisible, and yeasts have become big business.

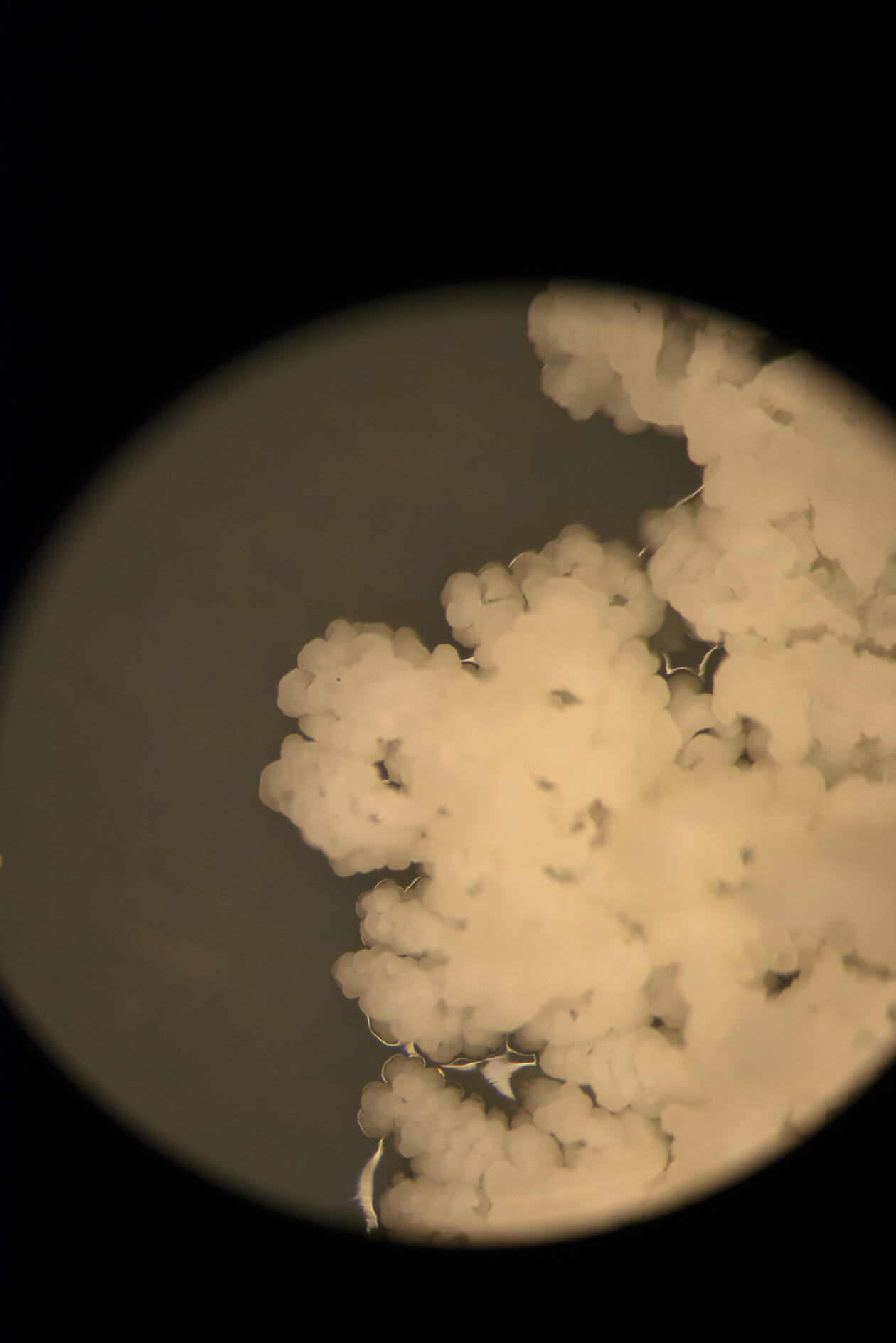

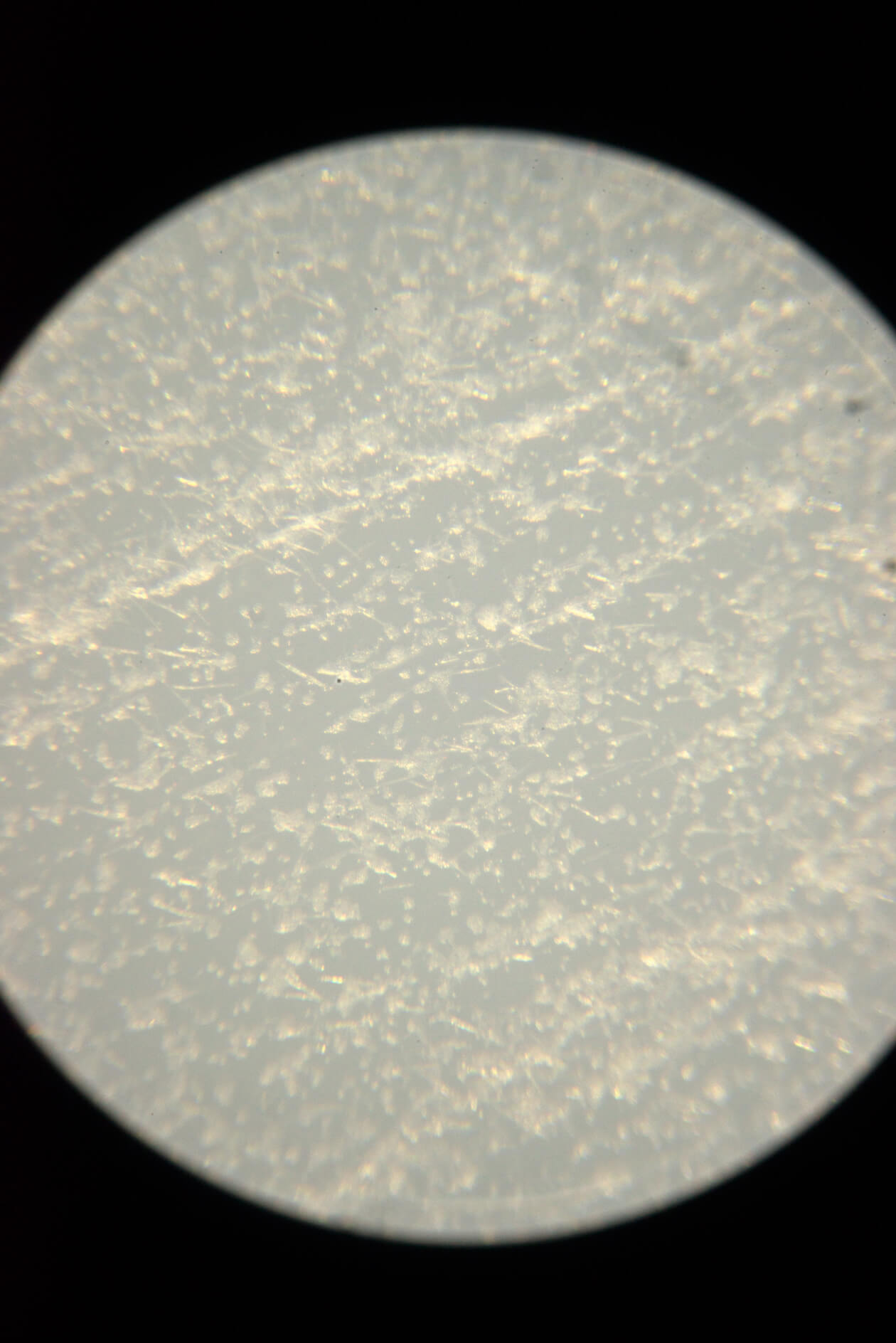

Back in Lachance’s lab at Western University, where he is a professor in the department of biology, he gets down to yeast wrangling: using what looks like a miniature metal lasso, he streaks the slime-flux sample on an agar plate, which feeds micro-organisms and allows them to grow. He places the plate into an incubator, which looks like a vintage don’t-make-’em-like-they-used-to fridge. In a couple of days, the distinctive shape of a wild-yeast colony should appear—a strangely pretty, lacy pattern of white pinpricks that almost resembles a form of Braille. Once the yeast colony is grown, Lachance will be able to tell what kind of species it is. If he’s lucky, it may be one that science has yet to discover.

Humans have been living with, cultivating, and using yeasts for millennia, long before we knew what they were. We’re still only beginning to understand how important they are in the natural world. Yeasts are everywhere: air, soil, orchards, vineyards, flower nectar, fruit. They live on our skin and in our digestive tracts.Saccharomyces cerevisiae, for example, is the sugar fungus that drives fermentation to give us bread, beer, and wine.Candida albicans, on the other hand, gives us yeast infections.

Only a fraction of the yeast species on the planet have been identified. We currently know of 1,500 species (of which Lachance has discovered 149; he has the genus Lachancea named after him), though Lachance pegs the potential total at 15,000. Other estimates have been ten times higher. Identifying a yeast strain used to take about eighty tests in a lab, but researchers are now able to go into landscapes with portable machines that can spit out genomic sequences to identify the sample. Meanwhile, hobbyists can go online to buy a Backyard Yeast Wrangling Tool Kit from Bootleg Biology and join the forefront of citizen science.

Yeasts have become a veritable “microbial workforce” in the biotech and health care industries, as Nicholas P. Money describes in his 2018 book The Rise of Yeast: How the Sugar Fungus Shaped Civilization. Yeasts have a cellular structure that is similar to humans’ and easy to manipulate. As a result, they are model organisms for research into genetics and cell biology. Yeasts are also used to make insulin, vaccines, leather, silk, riot-control spray, and ever-hopeful antiaging cosmetics. They are also touted as a potential key for future biofuels.

Wild yeasts have also become the darlings of the alcohol industry. Guelph-based Escarpment Labs, which launched in 2015, provides brewers with alternatives to commercial yeast strains. It now has a 1,100-strong collection, including a Nova Scotia sample dubbed “Driveway Carnage” and a variety that was mailed in by a yeast aficionado in Norway. Even Heineken recently released a “wild lager” made from a rare yeast discovered deep in Patagonia by microbiologist (and

Lachance collaborator) Diego Libkind.

The microbiome is having such a big moment that it’s hard to believe it’s been about 150 years since Louis Pasteur conducted experiments with grape juice to demonstrate that fermentation was the work of living microscopic entities. New breakthroughs are still happening regularly and can challenge our perceptions of the natural world.

Lachance recounts discovering a yeast species endemic to the Great Lakes region in a patch of morning glories near his campus. Lachance assumed that the Metschnikowia borealis, which has cousins from Florida to Costa Rica to Hawaii, grew in the flowers, but he later came to suspect that it lived in the gut of the nitidulid beetles that feed and breed in the trumpet-shaped blooms. When captured insects wandered over agar plates, they left behind looping trails that soon became yeast colonies. A colleague suggested that Lachance use Krazy Glue to prevent the beetles from excreting, and the evidence was right there on the plate—or, rather, it wasn’t. It appears the bugs aren’t just carrying the yeast inside them—they’re actually growing it on the flowers, likely for nutritional benefit. Although, the more we learn more about yeasts, the harder it becomes to tell whether we’re cultivating them or they’re cultivating us.