Anumber of years ago, around the time my grandfather was being moved into a nursing home, while cleaning out his study I came across a yellowing file folder. It was full of personal correspondence, including letters my father had written as a child in the ’50s. He wrote the first when he was seven:

Dear Daddy,

Thank you for the picture of the black bear. I have had bronchitis and I am not doing as I’m told. I hope you are having a nice time. I have not been reading my Bible very much. I have been praying. I am glad to hear that some girls are interested in getting saved.

A year later, he wrote again:

Dear Daddy,

I am glad many are getting saved and Mummy is too. I will be glad when you are home. Hope you are having a nice time and I want to know when you are coming home.

The folder held a dozen or so similar letters written by my five aunts and uncles—no great surprise, in a way, since for more than half a century my grandfather was an itinerant preacher in the Plymouth Brethren, a tiny clutch of fundamentalists so intent on escaping a sinful world that they declined to vote or serve in the military. The Brethren had no ordained clergy; they followed what Martin Luther called the “priesthood of all believers.” Yet they held a special reverence for full-time itinerants like my grandfather. Preaching was known as “the work”—as if there were no other kind.

Notable Members of the Plymouth Brethren

As listed on Wikipedia

Errol F. Richardson

- Robert Anderson: Head of Scotland Yard and Christian author.

- Thomas John Barnardo: Took in destitute male and female street children; founded Barnardo’s.

- Dr. Edward Cronin: Pioneer of homeopathy.

- Luke Howard: Chemist and meteorologist, the “namer of clouds.”

- Jim Elliot: Missionary killed by Waodani Indians along the Curaray River, in Ecuador.

- Ken Follett: Author of The Pillars of the Earth was raised in a Plymouth Brethren family.

- John George Haigh: Serial killer.

- David Hendricks: Convicted of killing his wife and children but acquitted in a retrial.

- Garrison Keillor: Radio personality (A Prairie Home Companion) and author; raised Plymouth Brethren; no longer associates with them.

As with all itinerants, the work required my grandfather to spend a lot of time away from his home in Huntsville, Ontario. He travelled for weeks and months at a stretch among isolated communities in northern Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritimes, preaching himself hoarse in French and English in mosquito-ridden canvas tents, cramped living rooms, and clapboard halls. Women vied with each other to board him in their homes. Men queued to ask his guidance through thorny passages of scripture. Reports filtered back from these surrogate families my grandfather stayed with, how he’d climb into bed and read stories to their children.

Reading my grandpa’s correspondence left me with a riddle: how could a man so present to perfect strangers be so absent with his own family?

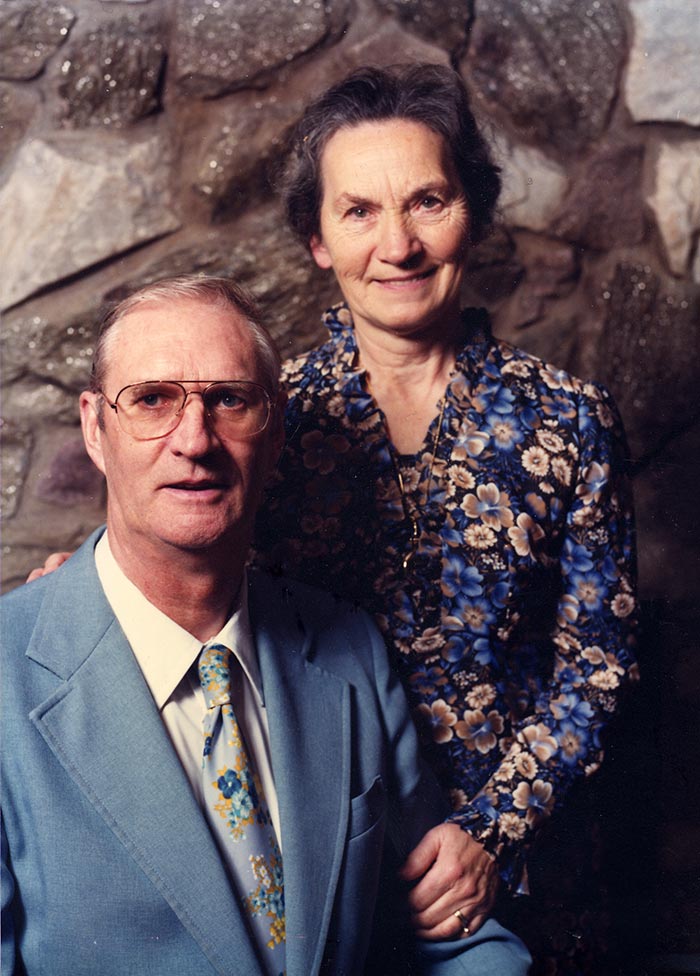

Like many popular figures, his public and private faces were hard to square. Behind the pulpit, he was all charisma. He could spend an hour piling image upon vivid image of the plight that awaited sinners in the world to come, tears rolling down his face. The times he was at home, he was a different creature. The gregarious performer became a skinflint with words; when coaxed into conversation, he would focus somewhere in the middle distance. Indeed, the company of familiars seemed to bore him. If he wasn’t sitting up to dinner or fixing something around the house, he would retreat to his study. On special occasions, he minded the minimal demands of hospitality and sat with us in the living room, redeeming the loss by reading his Bible or perusing a Reader’s Digest.

Though such behaviour struck me as incurious, even impolite, I accepted it as normal. Only in his declining years, after he had given up his preaching circuit, did I begin to see the ways in which it fit into a larger pattern of absence. Show me a man’s God, and I will show you the man, said Ludwig Feuerbach. The Brethren preached an absent God, one who had pitched his tent on earth for a mere thirty-three years before vanishing into the clouds. Wait until I come again, he told his disciples. And so every Sunday morning, the Brethren waited together for his Glorious Appearing, just as my father prayed anxiously each night for his father to come home.

When my grandfather finally passed on to his reward, the family gathered to share tales of the fallen patriarch. There was the time during a fishing trip when Grandpa failed to properly fasten the outboard engine to his boat. Out in the middle of the river, he yanked the cord, and the engine leaped into the air like a frightened fish and disappeared into the deep—a typical oversight for a mind less inclined to physics than metaphysics. Then there was that long, hot summer when my cousins succeeded in pilfering a ginger ale from my grandparents’ refrigerator. Returning to the fridge the following day, they found a hand-lettered sign: “Thou shalt not steal.” Over the rest of the weekend, we struggled to come up with a few more such memories, like the Israelites in the desert, pawing over a few crumbs of manna.

In fact, my fondest recollections of my grandfather come from his public ministry. In his hands, the Bible became more than a collection of ancient stories: it was the private journal of each believer, recording the pilgrim’s progress from birth to death, fall to redemption, exile to return. Every soul was Adam, treading a path of dust and thorns with a garden breeze wafting at his back; each heart a prodigal, stealing away from his father’s house to squander his riches in strange lands. Whenever he preached, my heart grew taut as it stretched to fit the biblical bow. I never felt so close to him.

I wonder now whether there wasn’t a bit of the prodigal in my grandfather’s wanderings. For fifty years, the peripatetic showman had thrived in exile, like a medieval troubadour or a travelling salesman. I wish I could say with certainty that he missed his family during those long absences, that he questioned the wisdom of his sacrifice. But as far as we know, Abraham never questioned God’s command to sacrifice his son Isaac. Jesus said, unless you hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, you cannot be my disciple.

No doubt there are other public men who decide that the full exercise of their gifts requires a similar choice. Are such men monsters, brute egotists incapable of intimacy, or do they seek an intimacy found only in the company of strangers? As my grandfather saw it, no earthly love could penetrate as swiftly or as deeply as that shared between a sinner and a messenger of the gospel. Intimacy was a moment’s work: laying out the biblical narrative, our benighted condition, and the all-important choice we may exercise over our final destiny. Once the matter was settled, there wasn’t much left to talk about. Time was short, and there was work to do.