One of the first things I did when I went to Scotland in May 2014, to report a story for the Toronto Star four months before the referendum, was meet with Norman Huggan, who lives in the house near Hawick that my Dryden ancestors left in 1834 to come to Canada. Norman had never voted before, he told me. Politicians say one thing, then do another. If you can’t know what you’re voting for, why vote? He hadn’t thought much about the referendum. He hadn’t talked about it with his wife and kids, though he thought they might vote Yes, or with “the boys at work.” The vote will happen, he said. The decision will be made. Independence or no independence, on September 19 he would be back to his landscaping business, planting, cutting, building stone fences, just as he will do on the eighteenth, the day of the vote, just as he has done almost every day for the last thirty-four years. He doubted he would vote, himself. If he did, he’d choose No: “Everybody says we’ll be better off in an independent Scotland, but they never say how.”

I went to a pub called the Waverley, one of about twenty bars in Hawick, population 14,500. I met Drew, Peter, Kenny, and Johnny. They are there every Thursday night. Why Thursday? I asked. “Because it’s almost the weekend,” Drew replied, as if it were obvious. Peter and Johnny are retired. Drew is a butcher. Kenny works in one of the town’s woollen mills. Hawick, located in the Scottish Borders, just north of the English frontier, is a two-hour bus ride south of Edinburgh. It’s the home of clothing manufacturer Pringle of Scotland. On Thursday nights, led by Drew, the four of them complain about everything. The cost of this, the stupidity of that, the crookedness of everything and everyone related to government. When I ask about the referendum, they say they don’t talk much about it. Each man says he would vote No—it’s about the only thing they can agree on—if he votes at all. “Too many unanswered questions,” says Peter. The economy, jobs, the pound, would they need a passport to visit family and friends just a few miles away in the north of England? They all nod.

I went to Inverkeithing, a twenty-five-minute train ride north of Edinburgh, across the Firth of Forth. Once the area had coal mines, then mills, then shipyards. Now it has a bridge that connects commuters to the city and not enough jobs. Two Yes supporters, hoping to generate local conversations about Scotland’s future, had organized what they called an Imagine Scotland Café. About forty people attended, most of them women over fifty. They were asked to answer two questions: What are your worries and fears for the future? What are your hopes for the future? No specific reference was made to the referendum.

They expressed worries about jobs, the National Health Service, the nuclear submarines based in Scotland, inequality, and adding one more uncertainty and one more division to their lives. One attendee wondered if an independent Scotland would feel bigger or smaller. Another worried that if Scots no longer had Westminster to fight, they would fight more among themselves.

They expressed hopes for more and better jobs, less inequality, and a nuclear-free Scotland. One woman said, the others nodding in agreement, that independence wasn’t the purpose. The point was to make Scotland an example. It was independence for something.

Two people were asked to give brief talks. Maureen, a woman in her late sixties whose husband, Leslie, was one of the local Yes campaign organizers, spoke of her journey to independence, from growing up in postwar austerity, through raising a family, to now. She recited a poem she had written, which ended this way:

With independence the future’s ours

An end to inequality

(To London—you’ll have had yer tea!)

An aspiration to be just

To end the greed of bankers’ lust

To every child a new tomorrow

Free from mithers’ war—grief, sorrow . . .

It’s me, our chance

It’s you? It’s us

We can, we should, we surely must

The other speaker was Ross. In his late twenties, he’d sold cars for a few years but was now unemployed. His partner, Kristy, was pregnant with their first child. He had been going door to door for the Yes campaign for months, “every Saturday, Sunday and most weeknights,” telling people of the need for an independent Scotland. It’s now or never, he said to them. It’s the chance of a lifetime. Every word he spoke, he spoke with body-shaking conviction. For Ross, the referendum had become his mission, to himself, to Kristy, to their unborn child.

But Ross was one of the exceptions. When I left Scotland in May, few others were paying attention to the referendum. A referendum is about politics—about “shouty, pointy men,” as they put it. It should be reasoned and reasonable. The stakes are too high for anything less. But having lived through two Quebec referendums, I could see that the people I met had no idea what was coming.

November 15, 1976, was the day of a provincial election that, depending on its outcome, would result in a referendum on Quebec’s and Canada’s future, and everyone knew it. The Montreal Canadiens were playing the St. Louis Blues that night at the Forum. Every fifteen minutes or so, the message board flashed the election results. Early in the third period, it showed “Un nouveau gouvernement.” There was a sudden roar that turned just as suddenly into a murmur of disquiet. When I looked up at the crowd through my goaltender’s mask, I saw thousands of people on their feet, screaming and yelling, and thousands more in their seats, silent. Until that moment, they had all been Montreal Canadiens fans, who had sat side by side as season ticket holders for years, even decades. But at that moment, they learned something about each other they hadn’t known before, and things among them would never be the same again.

My family was living in Montreal during the first referendum, in 1980, and in Toronto during the second. The 1995 vote was on a Monday. Both of our kids were born in Montreal, and we decided, the four of us, to reconvene in the city the weekend before the vote, just to be there. The Canadiens were playing at the Forum on Saturday night. Late that afternoon, I realized we needed to be in our seats early. The singing of “O Canada” would be a defining moment. When the anthem began, everyone was on their feet; it had never before been sung so loudly in the Forum. But while half of the arena sang its lungs out, the other half was quiet.

The passions had not yet begun to build in Scotland in May. Division, anger, pride—feelings people had no idea were in them, in their spouses, their sons, their daughters, their friends, their neighbours—that was all still ahead. Feelings that would surprise them and shock them, about others and about themselves. Feelings they wouldn’t know what to do with. Ordinary people, who’d never had power, feeling powerful. Politicians, the rich, big companies, who’d always had power, feeling powerless. Everything up for grabs—then the crapshoot of the final week. I knew I had to go again. I wanted to experience it with Norman, with Drew, Peter, Kenny, and Johnny, with Maureen, Leslie, and Ross, and with lots of other people in other parts of Scotland.

I arrive in Glasgow on the morning of Friday, September 12—“5 days 17:35:32” before the polls open, according to a message board at the airport.

The clunky, slab-stone Glasgow Royal Concert Hall, which opened in 1990, sits at the top rise of Buchanan Street, a pedestrian mall along which many of the city’s most popular shops are located. In front of the steps that lead to the hall is a statue of Donald Dewar, Scotland’s first first minister (1999–2000), his words carved in the statue’s base below: “There shall be a Scottish Parliament.”

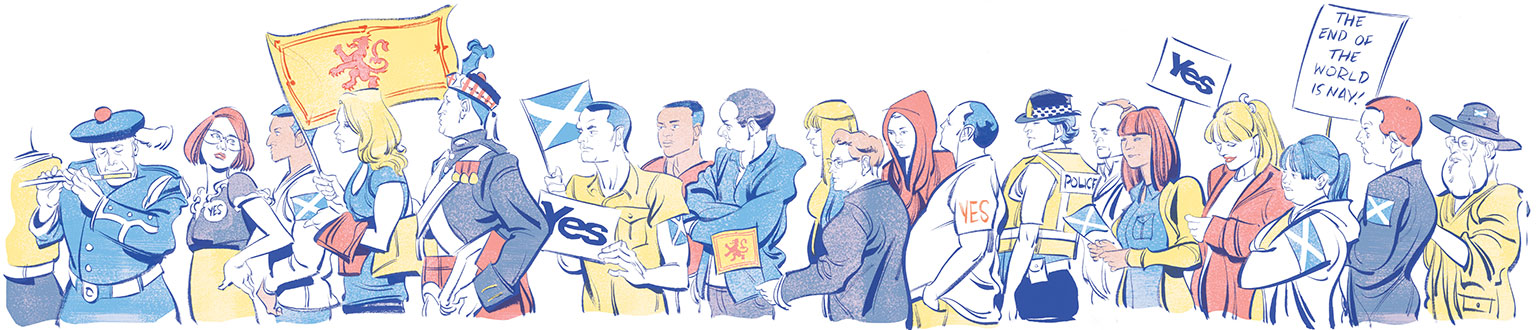

The Yes campaign has set up a table, covered with brochures and leaflets, near the statue. Its volunteers are scattered about, anxious to talk to anyone willing to talk to them. Four Yes supporters sit on the steps, each holding up a corner of the Saltire—the Scottish flag—superimposed with a large X beside a large Yes. Two hours from now, the No side will hold a big campaign event inside the hall.

I approach a man who seems only to be taking in the scene. What do you think? I ask him. At this stage in the campaign, no more needs to be said. James is a middle-aged photographer from southeast England who works in Glasgow. He has two older kids. “The Scots,” he tells me, “are a bit like the teenagers who live in an upstairs flat, raising a ruckus every so often, while downstairs the parents sit around sipping their tea, shaking their heads, wondering what’s going on. ‘What’s wrong with them? ’ the parents say to each other. ‘We’ve given them everything. Don’t they understand? ’ Then they go back to sipping their tea.”

A woman approaches me. “It wasn’t supposed to happen this way,” she says, without introduction. Elspeth, about fifty, is from Glasgow. She worked for the BBC—something she used to say with pride, she tells me. Now she is embarrassed by what she sees as the BBC’s biased coverage of the campaign. She reads the Guardian and follows public affairs closely, but has never been formally involved in politics. The 1999 creation of the Scottish Parliament within the United Kingdom had seemed the answer, she explains. “But all the power is in London, in Westminster. That’s where the population and money are.” It started with Margaret Thatcher, she says. “At the time when oil began to boom in the North Sea, when we mattered more than ever, she treated us like we didn’t exist.” The referendum is the result. “This campaign has been going on for two years,” she says. “And nobody noticed, except us, until a few weeks ago.” Now all the politicians are pouring north, she continues. “They talk about this glorious Great Britain. How important we are to it.” If this has ever been true, she says, “that Britain is never going to be again. It’s gone. Britain left us.”

The No rally features former prime minister Gordon Brown, himself a Scot, and Labour Party leader Ed Miliband. It’s not in the main concert hall but in an adjacent studio-like venue. Seats have been arranged in a circle around a small, slightly raised platform. The room has space for about 200 people, but 400 occupy it now. Brown speaks first.

Since the end of World War II, there have been three British prime ministers with significant connections to Scotland: Alec Douglas-Home, Tony Blair, and Gordon Brown. But Brown, born, bred, and educated here, is the true Scot. Although he was once a source of great pride to the Scottish people, his reputation diminished the higher he rose. As chancellor of the exchequer, as prime minister, why didn’t he make Scotland feel more connected and important to the UK? To many of his countrymen he became a vendu.

Often described as dour and tragic, tonight he looks anything but. Square-faced, square-bodied, he prowls the stage like a soccer defender, tenacious, hard-tackling, willing to stick his nose into the bloodiest of situations. He makes his arguments for the No side—the National Health Service will be protected, there will be new powers for the Scottish Parliament that will lead to “faster, better, and safer change”—but mostly his message is conveyed through his tone of pride and grit. The real independence we seek as Scots is not from this Union, he thunders, but from poverty, inequality, and injustice. “We are a nation forever—yesterday, today, and tomorrow.”

Miliband, up next, could not look more different. Young, slender, anxious, he turns quickly in the direction of his predecessor. “Gordon Brown,” he says, “you have the heart of a lion.” The crowd cheers loudly. Miliband tells a story about “Josephine,” whom he met during the campaign, and who works a minimum-wage job. How are you voting? he asks her. She is undecided. For Josephine, the referendum is about a higher minimum wage, Miliband tells his audience. It’s about building “a better life for everyone in the UK.” But that’s not what Alex Salmond, first minister of Scotland and leader of the Yes campaign, has made it, he says. Salmond has divided families and neighbours. This referendum is “his project.” No one asked for it. Neither Scotland nor the Union needs it. It’s for his own political gain. It’s about him. “A vote for No is not a vote for no change,” Miliband says as he builds to the end. It’s a vote to tackle the “great injustices of our time”—poverty and homelessness—together. “In the final days,” he says, “it comes down to us. Let’s go out and make the arguments.” He looks and sounds determined, yet he also looks as if he’d disintegrate were someone to boo.

Saturday afternoon: Four days, thirteen hours until voting day.

Neither side wants its support—but the Orange Order will have its parade. Wanting to know its route, I ask a policeman. He responds by asking, “To see it, or to miss it? ”

It goes on for more than three hours. Thousands watch from the sidewalks as 15,000 Protestant members of Orange lodges in Scotland, England, Northern Ireland, and Wales march through the streets. Men in dark suits; women wearing flouncy dresses, big hats, and fascinators; kids in adult outfits, looking adorable—every one a white face. Behind each lodge’s banner is its band, led by fifes, then snare drums, then bass drums struck with full-body whacks that rattle your heart. Marchers also carry banners special to the occasion—“Black Skull Glasgow says No”; “Redding and Westquarter Protestant Boys vote No”; “The Haw says Naw.” Many lodges also carry a common banner that reads, “Vote No. Proud to be British Proud to be Scottish.” Along the route, kids and their parents wave little flags—the Union Jack on one side, the Saltire on the other. But the atmosphere is good natured. There are no counter-demonstrations. On top of one bridge, high above the parade, with no head or hands visible, angled over the railing, is a single tiny sign. Yes, it reads.

Sunday morning. Three days, twelve and a half hours to go.

I go to St. Giles’ Cathedral, the High Kirk of Edinburgh, where in the sixteenth century Protestant reformer John Knox delivered his firebrand message. St. Giles’ is cozy, not soaring, its stone dark with age, its interior awash in a deep, warm, amber glow. It’s the third service of the morning; the seats are filled. In the scripture readings and hymns, I hear no subversive messages. In his sermon, the Reverend Dr. Douglas Galbraith says nothing about the referendum directly, but near the end of the service, in his Prayer of Intercession, he says this:

At this time of remaking of our life together, when so much seems uncertain . . . we pray earnestly for the good of each other and for the peace of each one. May we find at this time, in the ferment of discussion and argument, in public debate and in family life, an understanding of how we must be as a nation, and an energy to follow it through. May we turn from these debates with new insight, a new passion for justice, a new clarity about the strategies we should seek that make room for all.

Next Sunday, three days after the referendum, the church will hold a “service of reconciliation.”

Now it’s Sunday night, and a screen high above the stage at Usher Hall reads “3 days 11:23:16” when Eddi Reader sings her first note. A Night for Scotland is a Yes celebration. Almost 3,000 supporters, including Alex Salmond, are here to chant, cheer, wave the Saltire, and sing along with Scotland’s most beloved Yes musicians as they perform their signature pieces in the pounding, energetic spirit of the moment.

“I love the No voters so much, I want to give them a country,” Reader shouts, and the crowd roars. She sings “Wild Mountainside,” whose lyrics are inspired by the poetry of Robert Burns:

Beauty is within grasp

Hear the highlands call

The last mile is upon us

I’ll carry you if you fall

Rapper Solareye, of alternative hip-hop group Stanley Odd, performs a song he has written for his nearly one-year-old child, called “Son, I Voted Yes.” He takes his son through the events of his life—the “discontent winter” of Margaret Thatcher and later “a time of recession, food banks and destitution, worldwide turmoil with very little resolution.”

“Just simply voting Yes, the problem isn’t solved,” he intones. “But you can’t change the world taking no risks at all.”

At the beginning and end, and several times in between, the group’s vocalist Veronika Electronika interrupts Solareye’s rhythmic growl with her sweet, high-pitched refrain:

Son, I just wrote this

I thought you might like to know

That I chose to vote Yes

’Cause a Yes vote provided hope

What the future’s holding

No one can rightly know

I was tired of the same old script

And what’s next only time will show

Amy Macdonald, beloved for performing Scotland’s unofficial national anthem, “Flower of Scotland,” at international soccer matches, sings “The Leap of Faith” with her deep, throaty passion, performing it for the first time:

Standing on the water’s edge

Dreaming of a better day,

I’ll take the leap

I’ll take the leap of faith

“You know what to do, Scotland,” she yells as she leaves the stage.

Monday noon. Two days, nineteen hours to go.

In a 2013 survey, it was chosen as Scotland’s favourite word. The Oxford dictionary defines it as an adjective describing weather that’s “dreary; bleak”—and its origin, fittingly, is the Middle English for “patient, long-suffering.” The word is dreich. Monday is dreich.

Over the next three days I’m canvassing with both the Yes and No sides, to hear what they are hearing at people’s doors. Today, I’m with Yes and take a taxi to St. John’s Road, west of the city centre.

Yes organizers have unfolded a table on a sidewalk in front of an abandoned Woolworths; there’s a Yes banner covering the front of the table, and literature on top of it. Campaign volunteers mill about, talking mostly to each other. A few are aggressive enough to approach the rare souls out in the drizzly mess. Most people walk on by; a few take the material offered to them. One older woman, shaking her head at the offer, says, “I pray you don’t win.” Three storefronts away is Mike Crockart’s constituency office. He is the Liberal Democrat MP for Edinburgh West. The Lib Dems support No. A big Yes van is parked in front of Crockart’s office, in front of the No signs that cover his windows. Neither the van nor the table are where they are accidentally.

The Yes volunteers went door to door this morning, but misreading the weather they didn’t bring plastic to cover their canvass sheets, which got soaked. The result was a washout. They should have been in apartment buildings, going from flat to flat. Now, with the weather, there’s no foot traffic along St. John’s Road either. They decide to pack up.

Before the evening canvass, UK prime minister David Cameron gives his last big speech of the campaign, in Aberdeen. He has rarely set foot in Scotland during the campaign. From a strategist’s point of view, the logic seems inarguable. No is clearly, if not decisively, ahead in the polls. Most Scots don’t like Cameron. Why stir passions by waking a comfortably resting dog? Yet Cameron has stayed away even as the polls have narrowed, which seems almost unimaginable. With the Union fully and totally on the line, the prime minister not being there, not being on the ground, not fighting for its existence with every ounce of his being? How can that be?

This is the speech of his life. He knows it. His party knows it. The public and media know it. He stares into the camera. He appears comfortable. He speaks clearly: “This is a once-and-for-all decision,” he tells the British people. “If Scotland votes Yes, the UK will split and we will go our separate ways forever.” This is not a trial separation, but a painful divorce. No shared currency, no shared military, borders not so easily crossed—there are no question marks. This is not scaremongering. “These are the facts,” he says. “This is what would happen.”

But a No vote also does not mean “business as usual,” he says, for that “is not on the ballot paper.” A No vote means real change, he stresses. It means a major, unprecedented devolution of powers to Scotland. It means “faster, safer, fairer change.”

His tone turns more emotional. Once again, he says, with this vote, Scotland “is helping to shape the UK,” as it has done throughout history. The UK is “the best of both worlds.” We are a family, he says. “We are four nations in a single country. So please do not break this family apart.” On Thursday, he says, in the stillness of the voting booth, it’s up to you. “Don’t let anyone tell you you can’t be a proud Scot and a proud Brit.”

The speech lasts seventeen minutes. TV commentators say that despite laying it on the line as a “once-and-for-all” vote, Cameron is more hopeful than threatening, more emotional and passionate than he has been before. It is the pitch he should have been making throughout the campaign, they say.

The evening canvass begins an hour after Cameron has finished. I go out with Bob, about sixty, who owns a stamp and coin shop nearby. Early in the year, he began volunteering for Yes on some weekends. Then it became more weekends, then some weeknights, then more weeknights. Last week, he was away from his shop entirely, leaving it to his seven employees, and this week he will be going day and night until the vote. It’s still raining hard, but he seems not to notice.

We are in Carrick Knowe, a traditionally “upper-working-class, lower-middle-class” neighbourhood, as Bob describes it, a few miles west of the city centre. Other teams spread out on adjacent streets. These houses have been canvassed before. On his campaign sheets, this time covered in plastic, Bob has the name of every voter and whether they have said they will vote Yes or No or are undecided—“switherers” as the Scots call them. Earlier in the campaign Bob would go back to No houses to try to change their minds. Now there’s no time. He goes to Yes houses to thank them for their support, but mostly to make them know how much they matter, to ensure they will still vote Yes on Thursday. There are more Yes signs in the windows than No.

Bob also goes to undecided houses, or to houses where at least one person is uncertain. For those who are a challenge, he has the so-called Wee Blue Book. Pocket-sized, sixty-eight-pages long, and filled with, as indicated on the cover, “the facts the papers leave out.” At this point, people want to believe there are reasons behind their feelings. It doesn’t matter that few will read the book. That it exists is what matters. Most people are still not home from work, or aren’t answering. Bob knocks, waits, then slips his campaign material through the mail slot. With the distance between houses, the rain, and the unopening doors, his energy fades, only to pick up again when someone answers.

One man, in his thirties, gets excited when he sees Bob’s Yes pin. He works for Standard Life, the long-term savings firm. In the last few days, his company and several other big Scottish employers have said they will move their offices south if there is a Yes vote. The man is offended; he refuses to be bullied. “They’re in business to make money,” he says. “If there’s money to be made in Scotland, they’ll still be here. They don’t care.” He asks for a copy of the Wee Blue Book to show to people at work. Bob gives him one.

A woman in her early forties answers the door. Sounds of children come from the rest of the house, yet the woman seems to want to talk. She was undecided, but now she says she’s voting No. Bob asks why. “I’m from Italy. I know what change can do.” Bob steadies himself and says Scotland isn’t Italy, that change can mean good things too. She nods, but is undeterred. “I’m just starting to do okay,” she says. “I’m not rich. I’m not poor. I’ve got kids. I’m scared.”

It’s 8:05 p.m. and too dark to continue. No one has mentioned Cameron’s speech.

Tuesday afternoon: One day, ten and a half hours to go.

Stale donuts and cookies are strewn over the tables. About forty No volunteers fill a makeshift office to the east of the city centre, ready to take their marching orders. A young woman stands on a chair and tells them to remember to say, “If you don’t know, vote No. It’s up to Yes to prove their case. This is about faster, safer, better change.”

The volunteers go out at two o’clock and come back at four, some to go out again, and to go out a third time at six. The two o’clock canvass is in an old industrial and port area of north Edinburgh called Leith. Again, volunteers are seeking out No supporters and those who are undecided. Again, few people are at home. Some drive by, yelling insults or support. More Yes signs are in the area’s windows than No. As the canvass nears its end, a second-floor window opens and an older South Asian woman shouts plaintively to volunteers across the street; she sounds panicked, as if she is sick or her apartment is on fire. Then another face, this one very young, appears in the window. “It’s my grandmother,” the child shouts. “She’s saying, Vote No.”

In a central square where the volunteers begin to disperse, Yes has a table set up in front of a statue of Queen Victoria. A plaque at its base depicts the queen in a crowd, and reads, “Queen Victoria, Entering Leith, Sept. 3, 1842,” as if she were a foreign monarch.

The four o’clock canvass is not much better—too few people at home, too great distances to walk, volunteers with too much purpose and too few opportunities to satisfy it. The canvass at six is only slightly better.

Angela, one of the volunteers, is in her late forties but looks ten years younger. She is married with two kids, one of whom is a student at the University of Edinburgh who is also helping the No campaign. She and her husband lived in Canada from 1990 to 1996. He worked for Bell Helicopter in Mirabel, Quebec. They loved it there, she said, but it bothered her that her kids would have to go to a French school when other English-speaking kids, whose parents were born in Canada, didn’t. “I got tired of being told what to do,” she said. She got involved with the No side about a month ago, canvassing one weekend, then a few weeknights, until the last two weeks, during which she has been out almost every evening, and now, every day, too.

Canvassers aren’t good company this late in a campaign. They have been around too many people who think the same way they do for too long. They have grown more certain of their message and the rightness of their cause. Every assertion they make is the truth, every contradictory assertion a lie. They need this certainty; it gives them the courage to knock on the next door, shields them from the pain of rejection, provides them with the energy that keeps them going.

At the end of the evening, I take a taxi back to my hotel. The driver is in his late twenties. He came from Bangladesh eleven years ago. With his parents, his brothers and sisters, and now with their spouses and kids, his family numbers twenty. All of them live in the Edinburgh area. He says he is undecided, and when he hears my silence he says, “No, really, I haven’t decided.” Most people he takes around in his taxi will vote Yes, he thinks, and “I live in this community. I have to respect that.” But, he says, “people who teach at the university, learned people who have analyzed this, most of them think No. You also have to look at history.” Other countries at other times given the same choice: “Do you know how they vote? ” he asks. “Most say Yes.”

On September 19, he says, we’ll all know. And on the nineteenth, the sun will still come out, I add. “That’s right,” he says. “At seven. If you can see it.”

Wednesday afternoon Ten hours to go.

Leslie and Maureen meet me at the Inverkeithing train station. Leslie, who prides himself on organization, discipline, and reason, looks in a frenzy. He has a bad feeling that things are moving in a No direction. “It was that rogue poll,” he says, referring to the poll in the Sunday Times ten days ago that put Yes in the lead for the first time. “That was the turning point. Ironically, it galvanized the establishment and their message has taken over the agenda.” He drives to a school parking lot to meet up with other Yes volunteers. With only hours to go until the vote, they are slower than he would like to decide who should canvass with whom. “Volunteers can be like ferrets in a sack,” he smiles.

Ross is here, too, as he has been almost every day for the last several months. His partner, Kristy, has also participated in canvasses, but now, seven months pregnant, “she has to pee every twenty minutes,” so she’s had to give up going door to door. Ross is wearing a checked dress shirt with sleeves short enough that on his left bicep can be seen a tattoo of a Saltire with a Yes superimposed on it. Beneath it is Alba gu Bràt—Gaelic for “Scotland until judgment,” or, less literally, “Scotland forever.” “I knew I wanted to get something,” he explains. And if No wins, and they break all the promises they’ve made, as he’s sure they will, “I can pull up my sleeve and say, Well, don’t blame me.”

He canvasses with Stevie, who is about fifteen years older and just back from working several months on a big IT project in Malaysia. Ross goes to the doors. Stevie stands a few feet back with his canvassing sheets. It’s an area of older residents; more people are at home, the distances between houses are shorter. Ross keeps moving. “Hi, I’m Ross. This is Stevie. We’re from the Yes campaign. Can I ask you how you’ll be voting? ”

One man says he’s a Yes, but his wife is a No. When asked who will win, he shrugs. “But I do know the Scottish,” he says. “Next week, if there’s a No vote, they’ll be drunk, singing ‘Flower of Scotland’ and blaming the English.”

A tall, thin, older man answers at another door, “Well, I’m a Yes,” he says, “but my wife is a No, so you can cancel out this house.” Ross is undeterred. “Well, sir,” he says, “you have twenty-four hours to work on her.” A voice comes from inside the house: “No chance.”

A woman of about fifty is voting No; her son, Yes. Ross asks her why. From inside the house, another, younger voice: “Because she doesn’t know fuck all about politics.”

As they walk back to Stevie’s car, with the night’s final canvass still ahead, Ross says, “Coming from twenty-two points down in the polls to parity, Yes has won the campaign. Now we just need to win the vote.”

Seven hours to go.

Perth is a beautiful, ancient city of about 50,000 on the River Tay, an hour north of Inverkeithing, and less than half an hour from Gleneagles, where, as signs everywhere point out, the Ryder Cup golf tournament will be played in a week’s time. Alex Salmond has chosen Perth Concert Hall for his final campaign speech.

He begins with a story. In the last few days, he has heard No leaders say that if Scotland votes for independence there is no going back, and “that is absolutely true.” He recalls the recently ended, highly successful Commonwealth Games in Glasgow. He thinks of the seventy-one countries and territories that were there, and how almost every one of them has become independent of the British government in the last hundred years. “And you know what they have in common,” he asks, “these nations, rich and poor, large and small, lucky and unlucky? Not one of them, friends, has any intention of going back.” His audience, which had no idea where he was going, roars.

Over the next twenty-eight minutes, he delivers his message. “It’s the best opportunity we shall ever have. It is the opportunity of a lifetime,” he explains. “Scotland’s future must be in Scotland’s hands.” The crowd interrupts periodically, chanting, “Yes, we can. Yes, we can.” This is the biggest speech of Salmond’s life, too. Victory—a change in Scotland’s destiny—is possible, and it’s only hours away. Yet he speaks like a normal person asking other normal people for something that he wants them to understand is not reckless but logical. To his fellow Scots, who are desperate for reassurance, he is saying “Yes, we can”—but calmly. This, he concludes, is “our choice, our opportunity, and our time.” The crowd shuffles out of the hall, singing “Flower of Scotland”:

But we can still rise now

And be the nation again

That stood against him

Proud Edward’s army

And sent him homeward

Tae think again

Two hours, seventeen minutes to go.

It’s voting day, and newspaper headlines tingle with portent. The Scottish Daily Record: “Choose Well Scotland.” The Times: “D-Day for the Union.” Six people get on the bus for Hawick and for the towns and villages between. It’s Thursday, a workday, and the streets of Edinburgh are busy yet somehow quiet. The city turns quickly to countryside: the two-lane road winds gently past a vertical, grass-covered cliff, flecked with sheep, on one side, and rolling hills, streams, clusters of trees, and more sheep on the other. Everything is overgrown and achingly green. On a church lawn on a rise above the road, a big blue and white sign offers guidance: Try Praying.

On the bus, a woman in her mid-fifties is wearing a Yes button and holding a copy of the Wee Blue Book in her hands. Behind her is a couple in their early eighties. They are going to Galashiels for a day trip and will be back in Edinburgh late in the afternoon to vote: he Yes, she No. She is from England, the man explains. Every Monday to Thursday, for the last eight years, they’ve gotten on a bus and gone to a different place. It’s free if you’re a pensioner, he explains. Yesterday, they were in Dunfermline. “We meet people; we see things,” he says. “It keeps us active. And if we didn’t, we’d just sit in front of the telly.”

Hawick, too, is quiet. Fewer people are on the streets, fewer still are in the restaurants. At Ladbrokes, the betting shop, two punters watch several screens that carry horse races from around the country. Ladbrokes also takes bets on the referendum, but there isn’t much action. The odds on Yes are long—ten to three. On No, they’re two to nine. It’s said that one betting company, so sure of a No victory, has already paid off its No bets. During the second race at Listowel, a horse’s name catches my eye: Katimavik, which means “meeting place” in Inuktitut. The horse’s odds are ten to three. It finishes fourth.

At seven o’clock in the morning, when the polls open, there is already a line at each of Hawick’s eight polling stations. Voters stream in steadily throughout the day: a husband and wife with a daughter just old enough to vote and a son tagging along; a father with a child, a mother with a child; older people, with canes, being dropped off near the door; a woman with her two kids, who stay outside to kick a ball around until their mother comes back outside again two and a half minutes later. “I’m over the moon,” one election supervisor says toward the end of the day. “It’s only seven and we’re at 80 percent turnout already.” As for the vote, “I’ve a bag of gravel banging in my stomach,” one nervous Yes supporter says. No one knows how this will turn out.

Norman Huggan is stuck on the motorway in Birmingham. He’s been building stone fences in Leicester for the last six weeks. He had planned to be back, but he voted ahead of time, by mail, just in case. He had thought his family might vote Yes; he had no idea that his work crew felt the same. “I went with the family and with them,” he said, although in May he’d planned to vote No. “I thought maybe I’d missed something.” He shrugs: “If my income taxes go up, I’ll pay more. If they go down, I’ll pay less. That’s my life.”

No matter who wins the referendum, things may change for Norman next spring. In the thirty-seven kilometres from Hawick to Langholm, he says, the Duke of Buccleuch (pronounced “buck-loo”) owns hundreds of cottages and the land around them. The duke has owned Branxholme Woodfoot Cottage for all the years Norman and his family have lived there, just as he owned it 180 years ago, when my ancestors Andrew and Janet Dryden were tenants. Norman has heard that the duke is selling some of his properties. In June, Norman will ask to buy Branxholme Woodfoot Cottage.

I go to the Waverley Bar. Kenny had to leave, but the rest of the Thursday-night boys are there. Peter, Johnny (with his son), Paul, and Drew. They are talking about everything, and they’ve an answer for everything they talk about. Paul, fifty, who was working on a North Sea oil rig in May, wants to talk about the referendum. “If we’re going to have a government,” he says, “I want my liars deciding, not the liars from down there.” He builds up steam. “All those ‘Eee-tonians,’ those ‘Ox-fordians,’ or whatever they call themselves. Those rich bastards, they don’t care about us. They just want . . .” He stops himself and looks around: “Where was I going? ” “I don’t know,” Peter says. “You hadn’t gotten there yet.” Everybody laughs.

Paul picks up the thread again. “They just give us this big mountain of shite . . .” “Watch your language, son,” Johnny interjects—but Paul keeps going. After a few more “shites,” Johnny tells him again, this time with a little edge to his voice. Paul realizes he has gone further than he had wanted to. “Look,” he says, “this referendum’s been good. It’s like a couple getting divorced—no, it’s like before a divorce. You split, but you keep trying. You talk. Maybe you work out something better.”

Peter, who never says much, turns to Paul. “Look,” he says, “I feel the same way. I don’t disagree.” Then, with a little shake of his head, he says, “But too many questions.”

I go back to a polling station. It’s 9:30 p.m.; the polls close at ten. It’s almost deserted. The workers are cleaning up. On voting day, volunteers call people, arrive at their doors, and get out the vote. Today, they called and arrived, but nobody was there. People got themselves out. One more voter arrives. He is a jockey, currently not riding because of a broken collar bone. He has been a Yes supporter since the beginning of the campaign. He wanted to wait until the last minute to vote, he says, to see if somebody might say something or do something to change his mind—but nobody did. With seven minutes to spare, he’s here. Surely he’s the last. Then at 9:58 p.m., a man rushes to the station doors. He lives in Hawick and works in Edinburgh as a garage manager, making the 177-kilometre commute every day. He was in Luton today, just north of London. At 7:30 p.m. he caught a flight to Edinburgh and drove from there. He had to make it, he says. He, too, votes Yes.

Results, not even partial ones, won’t be announced for a few hours. Inside the Hawick Conservative Club, in a room that might accommodate 200, three men stand at the bar, with the bartender. They have been working at polling stations. They talk excitedly, not in anticipation of the result but about the turnout. One man shows me his sheets: in two polling stations, 845 of 924 registered voters voted. More than 90 percent. One woman he talked to was eighty, he says. “It was the first time in her life she had voted.” Outside, the empty streets echo.

Before 1:30 a.m., TV commentators commentate, but there is no news. Then Clackmannanshire announces, then Orkney, then Shetland—three sparsely populated areas, all for No. Dundee is the first to vote Yes, then West Dunbartonshire, but the momentum shifts again and for the last time. At 6:10 a.m., with a No victory in Fife, the referendum is statistically over. The bettors got it right. The final count: 55.3 percent No, 44.7 percent Yes. Slightly more than 84 percent voted.

It wasn’t love for the United Kingdom that impelled people to vote No. Nor was it a desire not to create an independent Scotland. It was risk—the devil they knew versus the devil they didn’t. As Peter in the Waverley Bar put it, there were “too many questions.”

I once wrote a biography of “an average guy,” called The Moved and the Shaken. The subject was in his early forties, was married with three kids, had a high school education, lived in a suburb of a metropolitan area (not unlike Carrick Knowe west of Edinburgh) and earned an average income as a credit card collector for a large oil company. Whenever anyone was asked to describe him, they would invariably begin or end by saying, “He’s just an average guy.” How would he have voted had he been living in Scotland, I wondered. I think he’d have voted No.

“Nothing to lose? ” he might have said. “I have everything to lose. It wasn’t easy for me to graduate from high school. It wasn’t easy to get this job, to learn it, to stay in it for twenty years. I may not have the best of all possible lives, but this is my life. I know how to live it. I’m good at it. Reshuffle the deck? I’d have to start all over again. I’d have to learn everything new. I don’t know if I could do it again. Do you know how hard it was the first time? Sure, some things might be better—but they might be worse, too. I live on the edge of things. Something goes wrong, what do I do? Quit my job? Who’s going to hire me? Move somewhere else? Good luck. Take my savings and start my own business? What savings? And what do I have to offer? I am where I am. I have to make this life work.

“You people love change,” he would say. “You think it’s exciting. And if it doesn’t work, you do something else. No big deal. Well, it is a big deal for me. You look down on people like me. We’re afraid of change. Well, live in my shoes for a while. I want the devil I know. I want a tomorrow I know. I might want an independent Scotland, maybe more than you do. But take a chance on an independent Scotland? I can’t.”

One day earlier: “They’re really paying attention, aren’t they? ” It was Ross walking from house to house, canvassing with Stevie. Ross, with the Saltire and Yes and Alba gu Bràth tattooed on his arm. Ross, who is on a mission for his unborn child. Indeed, “they” really were noticing—the big companies, the banks, all those politicians in Westminster pouring over the border like foreign dignitaries to tell the Scots how loved they are; all those newspapers supporting No; the BBC, Barack Obama, David Beckham, and David Bowie. Even the banker in the City who, when asked what effect the referendum would have on the markets, said, “Aw, it’s just the Scots.” They are all paying attention now.

I had thought the referendum would be about ancient passions, tribalism, and Braveheart. But kilts and bagpipes are for tourists, I was told. What it was really about was size: being small in a bigger and bigger world, and what to do about it.

The population of Scotland is 5.3 million. The population of England is 53.9 million. At the time of the Acts of Union in 1707, the population of England was about 5.5 million; Scotland was about a million. In this earlier, much smaller, and disconnected world, Scotland wasn’t insignificant. In today’s global world, it is tiny. And, being tiny, it no longer matters. It is merely a physical space, a geographical and geological accident, a place to store nuclear submarines and from which to extract oil.

But the Scottish people want to matter, as everyone does. Their referendum, like Occupy Wall Street, like Occupy Anything, was a cry of the powerless. The challenge for Alex Salmond, for David Cameron, for any government anywhere: How do you make small matter? Is it possible? Can anyone? Or is this the fate of globalization, unintended or not? Scotland mattered to the Union in 1707. It’s mattered since then, too. It played a big part in building the UK’s glorious past. Can it play a big part, or even a modestly significant part, in building the UK’s future? If not, why not become its own country? Why not matter to its own people? That is what the referendum was about.

Friday, September 19. Two hours and a twenty minutes after the vote.

In Hawick, fifteen or twenty people stumble onto the bus to Edinburgh. They’re tired with fatigue, and tired with relief—even those who voted Yes. It is cold and rainy. It is very quiet. But imagine this bus ride had Yes won: people tired but fitful, excited but anxious. Imagine the weekend and the following week. Imagine Norman. Imagine Drew, Peter, Kenny, and Johnny. The elderly couple from Edinburgh will still be off on their day trips. But imagine Cameron and Salmond. Imagine Ross.

At seven o’clock, the sun comes up. In the dreich air, nobody sees it.

This appeared in the March 2015 issue.