Eryn Dixon had enough to manage as it was. At the age of forty-five, with profound disabilities related to multiple sclerosis, Dixon was living in Almonte Country Haven, a long-term care facility on a grassy hill in eastern Ontario. Then, in March, she contracted COVID-19. As she lay unconscious and unresponsive, struggling on oxygen, her father, Rick, was told to say his final goodbyes. Against the odds, Dixon pulled through, but more than a third of her facility’s residents weren’t so lucky.

Hers is just one of so many stories that we have been reading and watching and hearing for months—a catalogue of media reports every day, documenting COVID-19’s progression through our communities and the various ways it takes its toll.

On May 4, Karam Singh Punian, age fifty-nine, did die of COVID-19. He was one of an estimated twenty Toronto airport taxi drivers who contracted the virus that month alone. Most of the 1,500 people who make their living driving passengers to and from Toronto Pearson International Airport are self-employed men who are newcomers to Canada. They work long hours in sedentary jobs and eat on the go, without access to health benefits or paid sick days.

In early August, Patrice Bernadel, a much-loved Montreal pastry chef, suffered from COVID-19 in a different way. Like so many people in the restaurant industry, Bernadel had seen his business devastated by the pandemic. And, like so many self-employed Canadians, he had no guaranteed access to mental health services outside his doctor’s office or the emergency department. “The economic, social and psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have destabilized his life to the point of diving him into a deep depression, preventing him from seeing the light at the end of the tunnel,” his brother wrote in a Facebook post soon after Bernadel died by suicide.

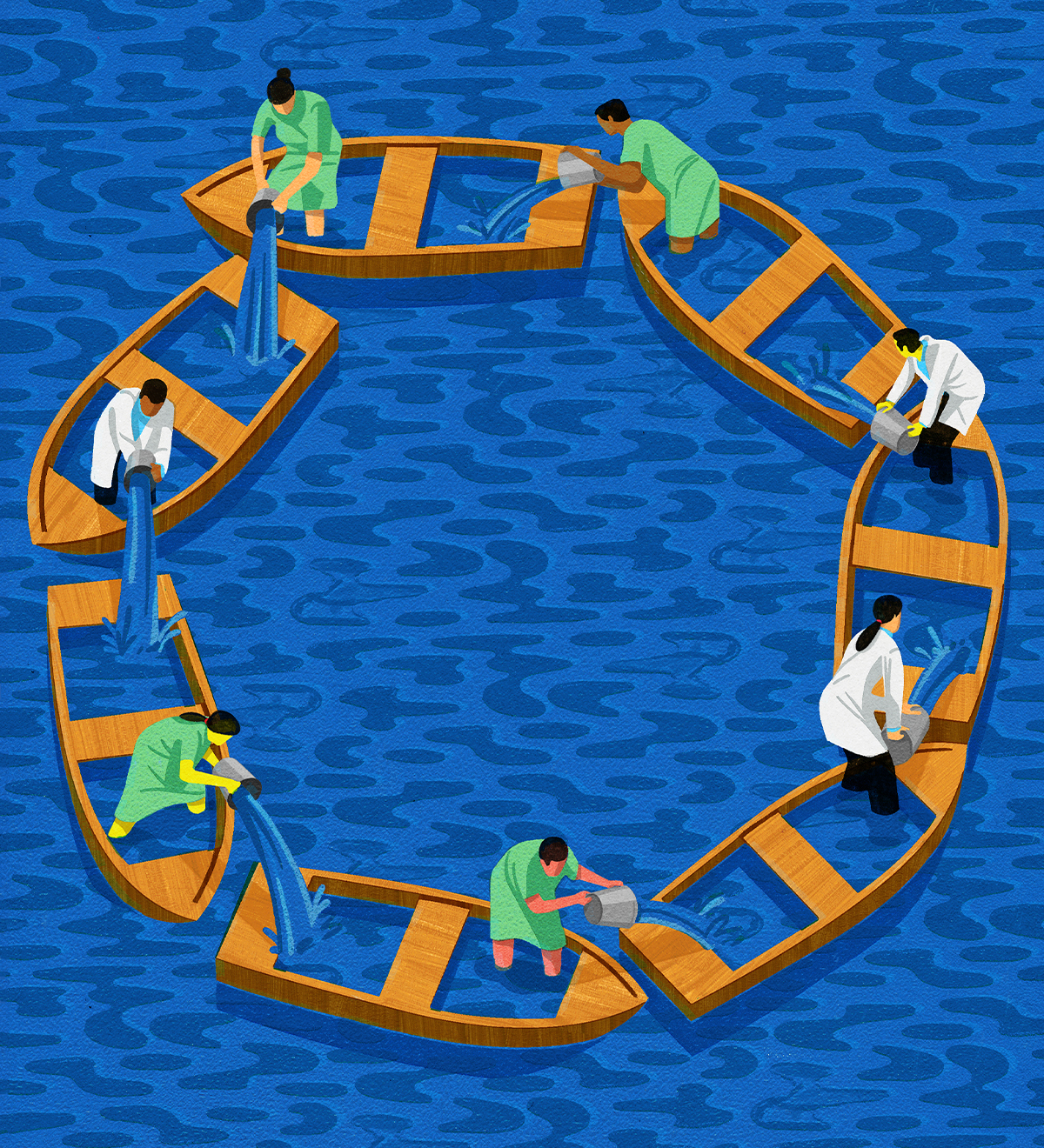

As COVID-19 took hold around the world in the spring, Canada prepared for one very specific kind of tragedy: the kind we saw unfold in Italy and in New York, one where hospitals were overwhelmed and ventilators in short supply. Thanks to good timing, hard work, and an economic shutdown that will have ripple effects for years, we have so far avoided that particular calamity. But, as Dixon’s, Punian’s, and Bernadel’s stories reveal, there are many kinds of tragedies: as a country, we were too slow to realize that there were—and are—other pandemic disasters happening all around us. The stories of COVID-19-affected Canadians are also stories about Canada and our health care systems—about which kinds of tragedies we go to great lengths to avoid and which we allow to persist.

By comparison with the death count unfolding south of our border, many Canadians have felt very proud of how our country and its health systems—thirteen provincial and territorial systems, with some areas of federal responsibility as well—rose to meet the initial crisis of the pandemic. Canadian medicare has always meant more than a set of public insurance programs: we are prouder of it than we are of ice hockey or the maple leaf. The notion that access to health care should be based on need, not ability to pay, is a defining Canadian value, surviving along the longest shared border in the world with the country that hosts the most expensive, inequitable, profit-driven alternative imaginable. That difference in values is often emphasized in our political rhetoric, as when Jean Chrétien would say, “Down there, they check your wallet before they check your pulse.”

We are two doctors working in very different environments and very different medical disciplines, and we have been seeing COVID-19 reinforce some basic lessons about Canada’s health care. First, our systems’ preexisting cracks become chasms when subjected to major shocks. Second, a conversation about health care that is divorced from the social factors that help determine how healthy you are is not really a meaningful conversation at all. And, third, perhaps the only lesson that should qualify as news: when they feel they have no alternative and the need is sufficiently great, governments, private-sector players, and individual people can make tremendous changes in very short order.

Health care systems exist to prevent and treat illness. What this means, as a matter of medical practice and health policy, is a matter of enormous ongoing debate. When Tommy Douglas implemented public health insurance in 1947, his Saskatchewan government focused first on covering hospitals and later on medical care—at that time mainly defined as physician services. This model spread across the country in the decades that followed, with the support of the federal government and its spending power.

Canada does a reasonably good job on these basics. Despite unevenness and variability, our national performance on a wide range of health indicators is generally strong. A person diagnosed with leukemia, for example, is less likely to die in Canada than in Ireland, Sweden, or France, the 2016 Global Burden of Disease Study found. Similarly, someone who experiences a stroke in Canada is likely to have a better outcome than is someone in the US, South Korea, or Singapore.

Just about any Canadian will tell you that the Achilles heel of our health care system—what is sometimes characterized as the price of these basics—is the wait time to get access to nonurgent care. It isn’t the kind of delay imagined by some American conservatives, in which “socialized health care” leaves people to exsanguinate on the sidewalk while they’re told to take a number. Rather, it’s the senior who, in line for a hip replacement, loses the chance to dance at her granddaughter’s wedding; the small-town teacher with chronic headaches waiting months for an outpatient neurology appointment; the parents, worried about their daughter’s shift in eating habits, recognizing that it will take months to get an eating-disorder assessment.

In the “new normal” of COVID-19, that problem is worse. Public health efforts to quell the spread of the coronavirus have been admirable and necessary, and the sacrifices within the health care system—delayed operations, cancelled clinic visits, postponed diagnostic testing—to prepare for a potential onslaught of cases were likely unavoidable. But the toll is steep and ongoing. Tens of thousands of cancelled procedures need to be rescheduled while hospitals grapple with a new reality that is much less efficient than the pre-COVID-19 world was. It is no longer prudent to have four patients in a single hospital room, let alone people on gurneys in the hallways; PPE must be conserved, so cases continue to be prioritized based on clinical factors; physical distancing must be respected. The high-volume churn of operating rooms for surgical cases is a thing of the past; everything just takes longer.

There are other layers of service, unattended to during the first wave, that may declare their impacts in the coming months and years. In primary care, immunizations were delayed, diabetes management put on hold, and routine visits for diseases like schizophrenia or high blood pressure forgone. In Manitoba, there was a 25 percent drop in administered measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines between March and April for children two and under, the National Post reported. Meanwhile, BC Cancer, a wing of the province’s health authority, estimates that, in the first six weeks after the pandemic was declared, almost 250 British Columbians unknowingly had silent cancers go undiagnosed as their screening mammograms, colonoscopies, and pap smears were cancelled.

And all that is still just the basics. Douglas dreamt of moving to a second stage of medicare, in which coverage would be much broader and the prevention of disease a bigger focus. That dream was never realized, and there are whole swaths of health care that are not included in our universal system at all. Instead, an ongoing emphasis on doctors and hospitals has led many observers to characterize Canada’s so-called universal health care coverage as “narrow and deep.” What we do provide (services like primary and specialty medical care, diagnostics, surgery) tends to be high quality; our health care system strives for equal access to care particularly by ensuring there are no financial charges for these services. If you are seen by a doctor or admitted to the hospital, if you need a CT scan or a blood test, if you require a biopsy or a specialist assessment, you will be well taken care of and never see a bill. But, if you are among the 20 percent of Canadians lacking adequate drug coverage and you walk out of your doctor’s office with a prescription for medication to treat your diabetes or high blood pressure or infection or depression, you may be on your own. If you require therapy with a psychologist for anxiety, or physiotherapy for your sports injury, or a root canal, your access will depend on your ability to pay.

THE COST OF CUTTING CORNERS

Debates about expanding our public health care plans to include medications, mental health care, home care, and a host of other medical services—and to move beyond treatment into true prevention—are as old as the plans themselves. Out-of-pocket health care spending (what you reach into your wallet to pay for, whether the full cost of a service or the co-payment or deductible) accounts for roughly 14 percent of total health care expenditures. Private insurance, often provided through our workplaces, accounts for another 12 percent. Of course, some of this is discretionary health spending (the massage you enjoy but that isn’t medically necessary, or that second pair of eyeglasses you get because they look cooler than your old ones do), but reliance on private spending and employment-dependent insurance is still higher in Canada than in most high-income nations.

COVID-19 teaches us about which kinds of tragedies we go to great lengths to avoid and which we allow to persist.

When one includes both public and private spending, health care amounts to 10.7 percent of our GDP, which is in the top third of OECD nations. But our government spending is actually lower than most of our comparator nations’. While 70 percent of health care spending is public in Canada, that number is 82 percent in the Netherlands, 77 percent in the UK, and 79 percent in New Zealand. Each of those countries’ universal health care systems includes both coverage of prescription medications with just nominal user fees and some degree of mental health care.

Canada has long had the dubious distinction of being the only country in the world with universal health care that doesn’t include prescription drugs. We also have less public coverage of home care, dental care, and non-physician care outside hospitals—which includes services provided by everyone from social workers to psychologists and physiotherapists—than most comparator nations. For example, New Zealand’s publicly funded system includes long-term care, mental health care, physical therapy, and prescription drugs in addition to hospital and physician care. In Germany, mental health care, dental care, optometry, and prescription drugs are all covered by mandatory universal health insurance.

While some public coverage for these services exists for some people in Canada, the amount differs by province and territory, and many people fall through the cracks. The result is that, in our purportedly universal system, many Canadians go without necessary services if they don’t have private insurance coverage, usually through their employers. And Douglas’s vision of a social democratic society that would take the broadest approach to alleviating the root causes of ill health—which include poverty, racism, and lack of education—has not dominated the political discourse for generations. Canada has moved so slowly on the journey to expand and improve medicare that it has been accused of a “paradigm freeze”—stuck in a system just good enough to prevent any major change or improvement from ever occurring.

Indeed, current interest in COVID-19 treatments offers up a potential irony for Canada. If the efforts of the international research community yield a treatment—a tablet or liquid that could be taken to prevent hospitalization or a ventilator—millions among us would have no coverage for it. “During the H1N1 influenza, [several provincial governments] announced that the antiviral medication Tamiflu would be available free of cost to anyone who needed it,” says Irfan Dhalla, a vice-president at Unity Health Toronto and a practising physician at St. Michael’s Hospital. “A similar approach might occur should a COVID-19 treatment become available. However, this equitable approach [raises] the question: Why should one prescription medication be available to all based on need and not others?”

In June 2019, then minister of health Ginette Petitpas Taylor tabled the final report of the Advisory Council on the Implementation of National Pharmacare. The report provided a blueprint for the stepwise implementation of a pharmacare program, developed in partnership with provinces and territories. In the context of a global pandemic, that partially shelved blueprint needs to be dusted off in a hurry.

If prescription drug coverage is one urgent and obvious area of expansion, mental health care is another. In 2019, the Public Health Agency of Canada found that 2.5 percent of respondents described having suicidal thoughts within the previous year. By May 2020, in the thick of the pandemic’s first wave, a survey found that number had more than doubled. Over and above the disruption experienced by all Canadians when the economy shut down, some people—including parents, people with preexisting mental illnesses, Indigenous people, those with a disability, and those who identify as LGBTQ—faced an increased risk of serious mental illness and suicide.

This is the curve after the curve: the increasing mental health toll of economic devastation, social isolation, and mounting uncertainty that follows on the heels of our commendable collective efforts to squelch the spread of COVID-19. On average, about 4,000 people in Canada die by suicide each year. A recent study suggested that, as a consequence of COVID-19’s impact on employment alone, that number could go up by more than 25 percent in both 2020 and 2021. By comparison, in the first ten months of 2020, just over 10,000 people had died in Canada as a result of the disease itself. “After a disaster, population rates of psychological distress tend to double or triple,” the Canadian Medical Association Journal reported in July.

Proposals for health care reform date back to long before the pandemic, but it took the pandemic to get action on implementing even some of them.

Expanding publicly funded pharmacare and mental health care—moving closer to the promise of “universal” care—could be achieved through a variety of means, the easiest of which is generally understood to be a transfer of federal dollars to the provinces and territories to support part of the cost of such services, on the condition that they be provided free of charge to everyone already eligible for general health coverage. In other words, it would look exactly like medicare does right now, and your health card would be all you need.

Canadians are already paying for these services, whether indirectly, by financing their workplace or private insurance coverage, or directly, by paying out of pocket for them. Each year, Canadians spend almost a billion dollars on mental health counselling, with 30 percent of that coming out of pocket. In the case of prescription drugs, we pay among the highest prices in the world because we don’t negotiate centrally. The report on the implementation of pharmacare put the price tag at $3.5 billion to launch a national program in 2022, with savings of $350 per year for the average family.

We are also collectively, out of the public purse, currently paying the downstream costs of having a segment of the population that can’t afford such services and is forced to suffer the consequences. Removing out-of-pocket costs for medications used to treat diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and chronic respiratory conditions alone would result in 220,000 fewer emergency-room visits and 90,000 fewer hospital stays annually, that same pharmacare report found. This would yield $1.2 billion a year in health care savings, just for those three common diseases. Similar results exist for mental health services. A 2017 study found that every dollar spent on publicly funded psychological services for depression would save Canada’s health system two dollars. Treating health conditions before they escalate and require hospital care improves medical outcomes, preserves quality of life, and saves money that could help offset the costs of program expansion.

UNIVERSAL FOR WHOM?

In the first wave of the pandemic, 81 percent of Canada’s COVID-19-related deaths were in long-term care (LTC) facilities. Our country was among the worst of all developed nations in preventing COVID-19 deaths in settings like the one where Eryn Dixon lived. A report from the Canadian Institute for Health Information concluded that countries with centralized regulation and organization of LTC, and those that implemented strict guidelines to prevent transmission of the virus at the same time as their lockdowns, fared best. In some parts of Canada, that didn’t happen until it was well past too late. Though some nonprofits fared badly and some for-profits did well, on average, the problem was worse in for-profit facilities, which had larger and more deadly COVID-19 outbreaks than their nonprofit counterparts did. The resulting headlines were scathing: “Majority of region’s long-term care deaths occurred in for-profit homes”; “Four out of five COVID-19 deaths have been linked to seniors’ homes. That says a lot about how Canada regards its elders.”

Well over 200,000 Canadians live in nursing homes or long-term care facilities. You know them; so do we. They are our parents living with dementia and frailty. Disproportionately, they are our mothers and grandmothers, the matriarchs of our families. On average, they are over eighty-five and face multiple health challenges, from chronic lung and heart disease to mobility issues to memory loss.

Many Canadians are placed in LTC sooner than they and their families would like—and prematurely exposed to the accompanying risks of living in a congregate setting—because they cannot access the supports and services they need at home or in their communities. And, no matter when a loved one is moved to such a facility, we should be able to expect some consistency in the quality of care they will receive. But, for many years in Canada, quality-of-care indicators, like worsening symptoms of depression or increasing pain, have varied significantly between homes, and worse outcomes have long been documented in for-profit settings in both Ontario and BC, including a higher risk of death. This is at least in part because staffing levels tend to be lower in for-profit facilities. In addition, personal support workers (PSWs), nurses, and other LTC staff are among the lowest-paid and most insecure workers in our health care systems. Many fell ill with COVID-19 themselves and, in some tragic cases, unknowingly transmitted the virus across facilities where they worked multiple part-time jobs.

COVID-19 “gives us an opportunity to reimagine LTC,” says Margaret McGregor, a family physician and a clinical associate professor at UBC medical school. “It’s time to change the staffing model in LTC so that PSW ratios of one worker to ten to fifteen residents are reduced to one worker to four to seven residents. This allows staff the time to provide holistic relational care. Much like daycare, these ratios should be funded, mandated, and enforced. More importantly, there is evidence that relational care, allowing staff the time to both care for and get to know their residents, improves seniors’ quality of life while improving PSWs’ conditions of work.”

An even more uncomfortable truth: health outcomes in Canada are very contingent on who we are and where we live. Race and class figure heavily in the COVID-19 story because they figure heavily in all health outcomes in Canada. Neighbourhoods in Toronto with the lowest incomes, highest rates of unemployment, and highest concentrations of newcomers consistently had twice the number of COVID-19 cases and more than twice the rate of hospital admissions than those at the top end of Toronto’s income spectrum did. People experiencing homelessness, seasonal agricultural workers, and those living in congregate settings (everything from rooming houses to prisons) were suddenly acutely aware that their proximity to others put them directly in harm’s way.

“Our initial response was focused on flattening the curve, not who was under the curve,” says Kwame McKenzie, an expert on the social causes of illness and the CEO of the Wellesley Institute. “But what is really worrying about these analyses is that they were predictable.” As of mid-September, the rate of those testing positive was 79 people per 100,000 for the white population. It was nearly seven times that for Black residents (547 per 100,000) and more than eight times that for Latin American Torontonians (643 per 100,000).

We’ve long known that race, newcomer status, and income drive health outcomes. For example, Canadians of South Asian origin are three times more likely than the rest of the Canadian population is to develop type-two diabetes, and they have a higher risk of dying from cardiovascular disease. We also know that not everyone accesses health care services equitably. Research from Ontario and BC shows that women who are new to Canada are less likely to have their breast cancer captured through screening, and wait longer to be diagnosed, compared with Canadian-born women. First Nations people in BC have well documented but poorly understood increased incidence and decreased survival for colorectal cancer compared with the rest of British Columbians.

But there is still so much we don’t know when it comes to how racism and bias affect both health and health care: most provinces and territories do not collect data about Indigeneity, race, or ethnicity in the health care system, so we lack the evidence we need to improve health equity. One crucial example: the COVID-19 rates of the 56 percent of First Nations people who live off-reserve are reflected only in the general-population statistics.

Urban communities are not the only ones left behind: as the second wave of the pandemic crests in many parts of the country, rural and Northern communities have struggled and will continue to struggle to access COVID-19 care, as they face challenges to access health care at all times. The concern about access to specialists and critical-care resources such as ventilators is of course most pronounced in such locations, where sometimes there are simply none within hundreds of kilometres. Prior to the pandemic, First Nations people, Métis people, and Inuit living in rural and remote areas already faced long wait-lists for specialist care and a shortage of available health practitioners, often delaying diagnoses and disrupting continuity of care. The distrust Indigenous peoples have in our health care system is informed by historical experiences in residential schools, Indian hospitals, and tuberculosis sanatoriums; it continues to be eroded by present-day racism. Hospital protocols limiting or eliminating family visits, while understandable efforts to reduce rates of COVID-19, may have perpetuated barriers for Indigenous people, many of whom feel unsafe when alone in health care institutions because of our country’s history and ongoing discrimination. One needs only to watch the video of Joyce Echaquan’s final moments to understand why. COVID-19 has exacerbated wait times for all Canadians, but where access was already poor or nonexistent, the burden is heaviest.

Five years ago, Canada accepted the findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report; in 2016, the country became a full supporter, without qualification, of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Despite these steps, disparities in the health and wellness of Indigenous people in Canada compared with that of non-Indigenous Canadians persist and, in some ways, are worsening. Poverty, crowded housing, unemployment, decreases to both quantity and quality of educational opportunities, struggles for food security, and diminished access to Indigenous languages, cultures, and traditional, unceded land—and the deep resilience and capacity that persist despite these impacts of colonization—all determine wellness and downstream health outcomes. Layered on top of these are the all-too-familiar elevated rates of trauma, suicide, addiction, and chronic diseases such as diabetes, autoimmune disease, and cancers—the root causes of which are all embedded in historical and current government policies.

But let’s take a closer look. First Nations individuals living on reserves were thought to be sitting ducks for a COVID-19 outbreak: many reserves are located in rural, remote, and Northern areas, have decreased access to culturally safe medical care, and have minimal or no local access to the type of medical care acute COVID-19 patients may need. Yet these “high risk” communities did not fare as predicted in the first wave. Indeed, the percentage of First Nations individuals living on reserve who reported positive for COVID-19 by the end of July was one-quarter that of the general population, and the fatality rate only one-fifth. So far, Inuit communities have been largely spared from the pandemic as well. How?

Many First Nations across the country closed their communities to outsiders in wave one by exercising sovereignty over their land and self-governance. Also key: the respect and priority naturally evident in First Nations communities for their Elders and knowledge holders, and their cultural reliance on the land. First Nations’ connection to the land has always been a vital part of their resilience as they protected the food sources, waterways, and traditional medicines that nourish their holistic health and well-being. For those who are often outdoors and in remote areas, physical distancing is a natural way of life. Is the rest of Canada capable of absorbing the lessons from Indigenous peoples and these practices? Perhaps we should.

Despite these better-than-feared outcomes, COVID-19 has taken its toll on Indigenous people in other ways. Take the opioid crisis in BC. In April 2016, the province’s medical health officer declared a public health emergency due to the rising number of overdoses and deaths. BC’s First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) released data in July demonstrating a tragic exacerbation of this crisis within BC First Nations during COVID-19. First Nations overdose deaths increased by 93 percent in the first five months of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019, and the percentage of First Nations people in the overall total of overdose deaths rose from 9.9 percent to 16 percent. (In BC, First Nations people constitute 3.3 percent of the population.) The FNHA postulates several explanations: an increase in drug use occurring when individuals were alone due to physical distancing, decreased access to and utilization of health care services, and increased toxicity of drugs as supply chains constricted during the pandemic. And the response to this crisis is markedly different. “When it comes to COVID,” Nel Wieman, the organization’s acting deputy chief medical officer, says, “the slogan essentially became, ‘We’re all in this together.’ And, when it comes to people who use substances, the thinking is, ‘I’m glad it’s you and not me.’”

Whether one is talking about newcomers in the urban core of our largest cities or Indigenous people on reserve, the interplay between health and social factors is complex. Sometimes, a COVID-19 death is a death by overdose, or by suicide, rather than by a virus; we may come to see more kinds of COVID-19 deaths before the pandemic is over.

BREAKING THE LOGJAM

That we are in the midst of an opioid crisis is not news. Nor is it news that the staff at long-term care facilities are underpaid, or that there are too few of them. It isn’t news that pharmacare is long overdue, or that wait times are too long, or that even a universal public health care system leaves vulnerable populations behind.

The real news is that we can do something about all these things.

The opioid crisis in BC has persisted for years, yet the province flattened its first COVID-19 curve in four months. What COVID-19 has shown us is that, in the face of a terrifying possibility—mass death, an overwhelmed health care system—the excuses we use to justify the status quo dissolve, and profound change can happen much more quickly than we are used to imagining. Some of the logjams in both our services and our thinking have been broken.

Early this year, even as hospitals were creating new critical-care wards and training their staff in the donning and doffing of PPE, other transformations were afoot. When Lindsey Longstaff’s seven-year-old son stepped on a nail this spring, she decided to try virtual care for the first time. Longstaff has severe asthma, and the nearest emergency department is in Regina, a forty-minute drive away, so she wanted to avoid a trip. After downloading a virtual-care app, Longstaff had an assessment with a nurse, sent photos of her son’s wound, and got a call from a doctor shortly afterward. She was told he didn’t need stitches and was shown how to clean and dress his wound herself—all of which was an exciting enough development in the speed and convenience of health care delivery that it got covered by CTV.

Before COVID-19, virtual care seemed a long way off in Canada. In 2018, only 8 percent of Canadians reported having had a virtual visit with their health care provider. Today, many providers and hospitals rely on virtual care to check in with patients and monitor their conditions. In one survey, more than half of respondents said their most recent health encounters, in April, May, and June 2020, were virtual. The overnight adoption of billing codes for physicians doing virtual care, allowing us to be paid for providing these online and phone services just as we are for in-person visits, was game changing. Assuming those billing codes are here to stay, many of us will never go back to a time when a patient needed to come in person for a simple issue that could just as easily and safely be dealt with virtually.

Canadians often assume that shortening our long wait times and expanding publicly funded services must involve more money, more hospitals, more operating-room time and more specialists. Of course, sometimes more resources are needed. But reorganizing and redeploying what we already have will get us pretty far.

A rich literature exists on how to fix wait times in Canada. Interprofessional teams, which include skilled providers like nurses, pharmacists, and physiotherapists, reduce reliance on doctors, who are often the bottlenecks when it comes to health care waits. Single-entry models—in which patients are given the next available appointment with any qualified specialist in their region rather than waiting for a particular specialist—improve flow by using a single, common wait-list for a given procedure. Reducing demand is also important: scaling back on low-value tests and procedures is difficult to do, but the potential benefits are extremely high. Both patients and doctors tend to believe that providing more services, in the way of tests, treatments, and procedures, will result in better health outcomes, but often that isn’t the case. When it comes to interventions, more isn’t always better. Strengthening primary care and home care so that most care occurs with a provider who knows you well and is easily accessible is key to eliminating waits for specialists. And, in this day and age, the use of technology, like the kind used by Longstaff and her son, holds enormous potential.

All of these have appeared in proposals and articles that date back to long before the pandemic, but it took the pandemic to get action on implementing even some of them. “For years,” says Chris Simpson, a cardiologist and former president of the Canadian Medical Association, “doctors have paid less attention to the unwanted clinical-practice variation that exists out there in the real world. Why do patients in one region get these tests and procedures at higher rates than other regions? The pandemic-induced slowdown . . . gives us an opportunity to look hard at our waiting lists. A hard look at appropriateness. A hard look at alternatives to surgical and procedural care, where appropriate. And a hard look at the huge clinical-practice variation in diagnostic testing. It’s an opportunity to improve the quality of the care we receive, to reduce low-value care, to enhance equity, and to use our resources in a wise and prudent way.”

But, perhaps surprisingly, the experiment that may have had the biggest impact on health during COVID-19 didn’t take place in the health care system at all. Virtually overnight, the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) and the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy stabilized the incomes of hundreds of thousands of Canadians; other emergency measures prevented residents from losing their housing. This is income support for the twenty-first century: easier to apply for, quicker to access and set up, structured not just to replace income but to supplement it. If we made programs like this permanent, reconfiguring them into a form of guaranteed annual income, the health benefits could be profound.

Much more than by MRI machines or surgery, health is fostered when kids grow up in safe households, with nutritious food on the table and access to education, in a climate free of fear and trauma. “When public health measures closed down large tracts of the economy in response to COVID-19, we had a system up and running in a matter of weeks that didn’t require mountains of paperwork or intrusive ‘means testing,’” says Evelyn Forget, an economist in the department of community health sciences at the University of Manitoba. “All that was required, it seems, was a change in attitude. COVID-19 showed us that we can break through what we thought were hard limits on our ability to deliver income security.”

This matters to doctors like us because financial stability is an even stronger influence on health than access to health services is: it’s social determinants of health, like income, education, and housing, that are far more influential. Between 1993 and 2014, in Ontario, residents of the poorest areas were more than twice as likely to die from a preventable cause than those living in the wealthier neighbourhoods were. People in the lowest income group are also less likely to receive health care when they need it and are 50 percent less likely than those in the highest income group are to see a specialist or receive care in the evenings or during the weekend. As the Canadian Medical Association has pointed out, there are hundreds of studies confirming that people in the lowest socioeconomic groups carry the greatest burden of disease. As a result, the CMA (among other bodies) has called for policy action to improve the social and economic circumstances of all Canadians. In time, we may learn that the CERB, widely viewed as an economic program, was the most important health program of the pandemic.

Every night, for the period of time when the nation was most intensely gripped with preventing the virus’s spread, people would come out onto their balconies and porches to clap and cheer, banging pots and pans as a way of thanking health care providers and other essential workers for their contributions to keeping people safe. Of course, we were glad to see those contributions celebrated in this way, and we are proud of our work and the work of our colleagues and friends at the front lines of health care. But we couldn’t help but feel that those of us who work in health care should be the ones saying thank you. The extent to which Canada has so far avoided the worst-case scenario, sparing us from having to work in untenable and terrifying circumstances, is only because of the actions taken by the public.

Physical distancing. Staying home. Socializing on Zoom. Wearing masks. Forgoing restaurants, movie theatres, visits to the gym, hugs with loved ones, birthday parties, long-planned trips. Scraping by without work. Working from home. Living on less. Home-schooling kids. Staying away from the bedsides of loved ones in the hospital. All this, and more, was done by each of us and all of us.

Perhaps the biggest news of the pandemic is that people who normally do not see themselves as powerful are exactly that. Whether Canadians feel it or not, we have proven that we have the power to protect and enhance the health of our communities. That engagement, that willingness to pitch in to protect others, is what can now be harnessed in subsequent waves, in the recovery, and in the future we will build together. What remains to be seen is whether that power will indeed be harnessed.

In the 1964 report that formed the blueprint for national medicare policy, justice Emmett Hall recommended that medications be included in Canada’s public health care plans so that people would not have to depend on their employers to ensure treatment. Recommendations to increase accountability and quality in long-term care date back to the 1966 Final Report of the Special Senate Committee on Aging in Canada. In 1974, Marc Lalonde, then minister of national health and welfare, issued a report called A New Perspective on the Health of Canadians, in which he recommended that public health interventions should focus their attention on people with the highest risk of exposure to disease, such as those living in poverty. And, in 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report called on the government, “in consultation with Aboriginal peoples, to . . . close the gaps in health outcomes between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities.” The problem isn’t that we don’t have a plan.

In 2018, The Lancet published a special issue on Canadian health care. One of the two central papers (which we were privileged to co-author with a diverse group of researchers from across Canada) argued that this country needs a renewed social contract. “Universal health coverage is an aspiration, not a destination,” we wrote. Since then, the fallout from COVID-19 has served to further unmask the gaps in our health care that have long been written about by scholars across the country. It’s well past time to expand the core basket of medicare services to include pharmacare, mental health care, and other medical services we currently ignore, and to reimagine how health services are delivered in order to eliminate wait times for non-emergency services. To design progressive home-care services and smaller home-style institutions that could provide older people with the dignified care they deserve. To address suicide, mental health, addictions, chronic diseases, life expectancy, and the availability of health services within Indigenous communities. To treat the biggest causes of ill health—the ones that are rooted in social and economic inequity—instead of only the ones we find easy to identify under microscopes and in operating rooms.

The familiar refrain for many followers of health and social reforms in Canada has been that we know what we need to do, we just need to do it. Now, through force of circumstance and perhaps without meaning to, we have finally begun the work. A terrifying glimpse of our own vulnerability has broken the logjam of health system reform, of income stabilization reform, of public and citizen engagement in health. Maybe this pandemic can mark a shift from wishful thinking to responsibility—from aspiration to expectation about what we actually mean and what we actually deliver when we say, so proudly, that our health care system is “universal.” We used to talk about whether big change would ever be possible. Now we know it is.

The O’Hagan Essay on Public Affairs is an annual research-based examination of the current economic, social, and political realities of Canada. Commissioned by the editorial staff at The Walrus, the essay is funded by Peter and Sarah O’Hagan in honour of Peter’s late father, Richard, and his considerable contributions to public life.