Early one October, Nick North arrived at a Calgary hospital feeling a mix of fear and excitement. He had long felt that his body did not match who he was inside: he had been assigned female at birth but did not identify as a woman, and the day had finally come for his gender-affirming top surgery, a procedure to masculinize his chest. But, he recalls, when he handed his paperwork to staff, he had to repeatedly request they call him Nick, not the name on his birth certificate. “If I already know you can’t figure out my pronouns and call me the right name, then how do I trust you with my unconscious body?” North says. “How do I go into that not terrified?”

North remembers hospital staff telling him not to take it personally, but “you always take it personally,” he says. It had felt just as personal when his psychiatrist told him to wear a swim top to feel more comfortable at the pool with his kids, leaving North to educate him on why having a body he feels comfortable in—not a swim top—would help his dysphoria.

North believes a federal survey on transgender identity could improve services for men like him. “There are so many more of us than you know, and we’re not getting the proper health care.” Research has suggested that gender and sexual minorities experience worse health outcomes than the rest of the population. Until recently, agencies like Statistics Canada have faced challenges in trying to collect health data on LGBTQ individuals in a manner that is both precise and culturally sensitive. Increasing the amount of publicly available data on the national level could allow health care practitioners to make more-informed decisions about patients. “If you can’t be counted,” says Lori Ross, a professor of public health at the University of Toronto, “then you don’t count in terms of policy.”

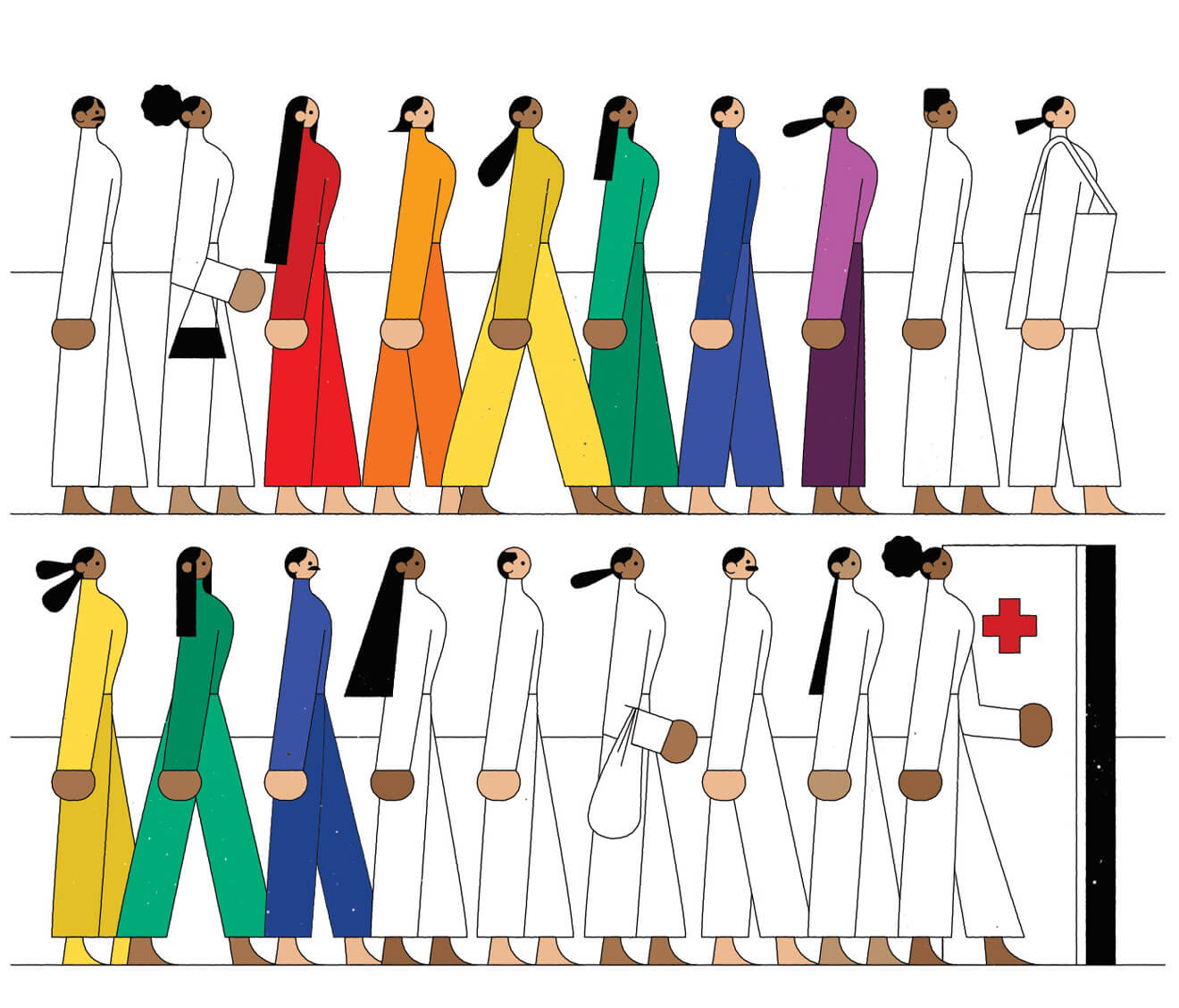

Last June, the federal standing committee on health, a small group of MPs with a key role in crafting legislation, produced a landmark report on LGBTQ health in Canada. Tasked with examining the numerous health inequalities for gender and sexual minorities, the committee collected evidence of disparities: bisexual women and lesbians are at greater risk of chronic illnesses such as arthritis, for instance, and LGBTQ individuals in general have disproportionate rates of mental illness. The report emphasized that discrimination and the stress of being a minority affect these health outcomes. In other words, the health care system marginalizes LGBTQ people because it isn’t designed to acknowledge them. Experts like Ross say that simply counting sexual and gender minorities in population-based data would help the health system respond better.

The report made several recommendations relating to data collection. It suggested Statistics Canada change its practices to increase the number of LGBTQ respondents, improve its questions on sexual orientation, and include sexual-orientation and gender-identity questions on all surveys.

As a queer nonbinary person, Brent Saccucci’s sexual and gender identities are integral to understanding their health needs (Saccucci uses he and their pronouns). A PhD student and instructor at the University of Alberta, Saccucci researches queer mental health and social justice. They trace their experiences with mental illness to widespread social stigma around queerness, “which makes me nervous of sex with men.” They are also anxious about getting HIV and have to take pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, a preventative drug. “It’s all intertwined: the sex, the sexual health, the mental health—all are deeply affected by being queer and trans.”

Saccucci has struggled to find affirming, queer-competent health professionals. “I remember one time I was at the doctor and asked, ‘What else can I do to mitigate the risk of getting HIV?’ The doctor was like, ‘I guess you could have fewer sexual partners.’” This didn’t sit right, and instead it was Saccucci’s therapist who calmed their fears.

Jody Jollimore, the executive director of the Community Based Research Centre, a nonprofit that promotes the health of gay men, says that the federal government must prioritize LGBTQ health, which could include gathering more public-health data. Federal surveys can help set health priorities: census data is used to make recommendations on long-term care for seniors, for example. According to Jollimore, “there’s a real gap between what’s getting funded and where the actual issues are” for queer and trans Canadians. For instance, access to PrEP still varies by province; Saccucci could not get it in Ontario but can in Alberta. More data on the experiences of those like Saccucci would make it easier to develop health standards across the country.

Alex Abramovich, a scientist with the Institute for Mental Health Policy Research at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, spent over a decade sharing with city council the concerns he heard from homeless LGBTQ youth, who often experience discrimination in the shelter system. In 2013, Abramovich was put in charge of a working group that advised the city to add questions about gender identity and sexual orientation to that year’s Street Needs Assessment.

According to that assessment, at least 20 percent of youth in the shelter system are LGBTQ—and that was a conservative estimate. Without this kind of data, says Abramovich, government and decision makers can “say there isn’t a problem or that we don’t really have an issue of LGBTQ people being overrepresented in, for example, homelessness.” Evidence from those new questions helped create Canada’s first transitional housing program for LGBTQ youth. Similar data sets at the federal level could have equally profound implications for services and funding.

Over the past two decades, Statistics Canada has begun addressing the data gaps on sexual minorities. In 2001, the census began collecting data on same-sex common-law relationships. In 2003, the annual Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) began asking respondents about sexual orientation, with the General Social Survey (GSS) following suit the next year.

These measures, however, still fall a few colours short of a full rainbow. Travis Salway, a professor of health sciences at Simon Fraser University, counts around nine publicly available federal data sets from the US on sexual and/or gender minorities that are useful to researchers: these government-run national surveys include a drug-use survey and a questionnaire on aging. To Salway, the only comparable resource in Canada is the CCHS. Researchers, he adds, depend on these data sets to conduct their work. And any increased data sets must be matched by funding for research and services; data alone can’t fix the problem.

Salway’s research shows that sexual minority adults are four times more likely to attempt suicide than their heterosexual counterparts; to identify whether these kinds of disparities are getting better or worse (and for whom), accurate and nuanced federal-survey data is crucial, he says. The Canadian census counts only sexual minorities who are married or living together. Additionally, the GSS and the CCHS are done by phone. “You can imagine, being asked over the phone by a government interviewer about sexual orientation, that it would be sensitive,” says Lori Ross. This discomfort could affect the survey’s ability to provide accurate population estimates.

Statistics Canada is working to address the problem of insufficient data on trans people as well. It has created two new questions that could be used in various surveys: one asks for sex assigned at birth, and another asks about current gender identity. The latter question allows for write-in answers that let respondents identify beyond the male-female binary. It has been launched on social surveys such as the GSS and CCHS, and Canadians may even see it on the 2021 national census.

Meanwhile, many in the LGBTQ community are finding their own ways to bend the health care system toward equity and healing. Trans Pulse Canada, for instance, is a national, community-based survey with the tagline, “In this census, trans and non-binary people count!”

Nick North has created a community of other trans people and allies that offers support, advice, and commiseration. North experienced complications in his top surgery, so he needs a revision, which recent changes at Alberta Health and a system under pressure have delayed for months. At times, he says, he felt like the surgery would never come, but it has now been scheduled for this spring.

For Brent Saccucci, creating a supportive health team has involved enduring many uncomfortable appointments with uneducated or insensitive service providers. Saccucci worries about whether Alberta’s United Conservative Party government will remove universal coverage of PrEP, which would make it inaccessible to them and those without private insurance. Ultimately, however, in spite of a health system they describe as “exhausting at times,” Saccucci has created their own path to wellness. They’ve even found a therapist with whom “my queer identity seems to fit.”