Who among us has not felt the affront? Macadamia nuts arrive in a bag, not on a dish, and something shrivels in the soul. Are we animals? Did we execute the challenging task of being born insanely wealthy only to eat in-flight snacks from a bag? We did not. And that is why, when Korean Air heiress Cho Hyun-ah was confronted by a bag of nuts on a flight out of New York in December 2014, she became enraged and forced the plane back to the gate. Now forty-one, Cho, daughter of the airline’s chairman, Cho Yang-ho, was charged with offences including assault and obstructing an airline captain in performance of his duties.

Cho was expected to serve ten months in prison; however, after an appeal, the sentence was suspended, and Cho was released on the condition that she not commit another crime in the next two years. Many observers consider the sentences too light, given the rampant nepotism and privilege enjoyed by second- and third-generation members of South Korea’s business elite. “If she were considerate to people, if she didn’t treat employees like slaves, if she could have controlled her emotion,” the chief judge said, “this case would not have happened.” But consider the deeper truth of the matter: it was not really her fault.

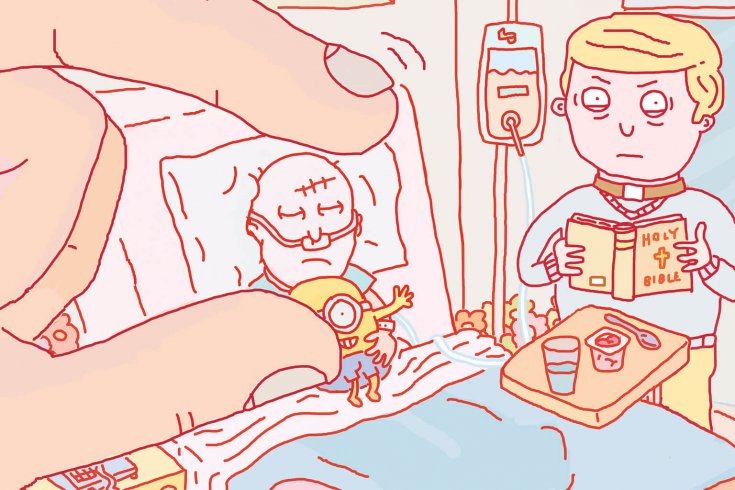

The psychologist Paul K. Piff has shown that there is a reliable correlation between wealth and inconsiderate behaviour. Wealthy people are more likely to exhibit rudeness in cars, take more than equal shares of available goods, and think they deserve special treatment. Cho is just a spectacular example of what happens daily at any airport. When the sheer luck of the birthright lottery is converted via psychological magic into a sense of entitlement, expectations of special treatment are predictable. Piff has coined a memorable label for the phenomenon: the asshole effect.

The asshole effect confirms experimentally the arguments of philosopher Aaron James’s 2012 book, Assholes: A Theory. Like George W. Bush, some people are born on third base and think they’ve hit a triple. That’s why Cho’s charges and sentencing should be seen for what they are: a show trial. Pictured in tears after the sentencing, Cho wrote a forced confession in which she stated, “I know my faults, and I’m very sorry.” This is Galilean recanting for the plutocentric age. But Cho’s conviction changes nothing. In fact, it allows the current arrangement to endure under a veneer of bogus accountability. Meanwhile, those who complain that the verdict is rooted in resentment are right. Resentment, after all, is the rational response of non-jerks when faced with the over-entitled behaviour of jerks. It’s not the rudeness that people hate so much as the assumption jerks make that they are allowed to be rude.

This isn’t always a function of wealth—often it’s just of narcissism and assumed superiority. I know several witless academic egomaniacs who routinely give themselves a free pass to be uncivil. But because wealth is the most obvious marker of status in capitalist societies, it is also the most powerful lever of assholery. It is no coincidence that the depredation of such people occurs most often in cases where they are confronted with the tedium of dealing with service people or, worse, of competing with other citizens for the attention of such service people.

Eric Schwitzgebel usefully supplements James’s asshole theory with his own theory of people he prefers to call jerks. “Picture the world through the eyes of the jerk,” he writes at the beginning of his field study of the type. The “line of people in the post office is a mass of unimportant fools; it’s a felt injustice that you must wait while they bumble with their requests. The flight attendant is not a potentially interesting person with her own cares and struggles but instead the most available face of a corporation that stupidly insists you shut your phone. Custodians and secretaries are lazy complainers who rightly get the scut work. The person who disagrees with you at the staff meeting is an idiot to be shot down. Entering a subway is an exercise in nudging past the dumb schmoes.”

Other entitlement show trials were underway in the early months of 2015. Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the former head of the International Monetary Fund, was scrambling to salvage the shreds of his reputation even as lurid evidence emerged of sex parties and pimping that make his alleged 2011 assault of a Manhattan hotel worker seem like business as usual. (Ken Kalfus’s novella, Coup de Foudre, is a brilliant fictional account of the latter incident, framed as a cringe-making letter of apology.) And, lest we forget, there are worse things than nut rage or even non-fatal sexual assault. Francesco Schettino, disgraced captain of the Costa Concordia cruise ship, wrecked off the coast of Tuscany, in 2012, was convicted of multiple counts of manslaughter. Thirty-two passengers and crew died in that debacle, and Schettino, who jumped ship, was sentenced to sixteen years in prison.

But while this “reckless idiot” was entertaining his twenty-five-year-old Moldovan mistress, ordering a pointless and dangerous flyby to impress her, there were a company, a system, and a set of assumptions all holding him up. His orders, after all, were obeyed. It is a necessary premise of law that individuals are responsible for their actions, and no sane person would have it otherwise. But the root causes of the asshole effect are not, finally, singular. Such people are made, not born. Until we have a more aggressive plan for attacking luck entitlements, condemnation of a few hapless exemplars will remain satisfying but futile.

Where to begin? The first thing to consider is what we might call the generalization of jerkitude. When Schwitzgebel fleshes out his field study of the species, he notices an important thing: while jerkiness may pool and settle in the declivities formed by other privilege (especially wealth and attendant social status) there is a surprising comprehensiveness to the jerk-like behaviour when any differences in status are in play. That is, I may not be a jerk most of the time—except in situations where I feel myself superior. Suppose I am a pedestrian and you are a motorist. I may indulge my inner jerk to such an extent that I hurl an insult, step in front of your car as it makes a rolling red-light turn, or otherwise perceive you as someone in my way.

The jerk’s failure, Schwitzgebel argues, is at once moral and intellectual. The moral part is perhaps more obvious: the jerk behaves badly and then justifies the behaviour to himself. But the path of justification is significant, typically involving a tangle of self-serving attitudes (I am in the right compared to you), narcissism (I am better than you), and errors of fact (I am correct, and you are wrong). The moral wrong of behaving badly is joined by the intellectual wrong of distorting facts and other elements of the given situation such that they run in the jerk’s favour. In sum, Schwitzgebel argues, “the jerk culpably fails to appreciate the perspective of others around him, treating them as tools to be manipulated or idiots to be dealt with rather than as moral and epistemic peers.”

The interpersonal aspects of Schwitzgebel’s theory mark it as superior to James’s asshole theory—to which, admittedly, it owes a great deal. An asshole, according to James, whether born or made, is someone who lays implicit claim to special treatment because of an entrenched sense of entitlement. We might say that, once confirmed in such a sense, the asshole reifies into a perpetual version of himself or herself. Cho might have apologized during her trial, but Strauss-Kahn was still treating the prosecutor with the same disdain he brought to maids: Why were they pestering a man about his private appetites with these absurd and intrusive questions?

The jerk relationship, by contrast, is more complex and more fluid. For one thing, it is always at least dyadic (me and the driver; the airline passenger and the flight attendant), though sometimes it is a series of multiple dyads (all those people queued up in front of me). The latter condition can make the situation look like it is one of reified assholery; perhaps in some cases, where there is indeed entrenched privilege, it is so.

But since one premise of the jerk theory is that any one of us might be a jerk at almost any time, given the right conditions—a bad day at work, cramped travelling conditions, too much humidity—there is more to the failures here than cases of what we might call Excessive Entitlement Disorder, or EED. Presumably, most of us do not suffer from this condition; such people are merely the bellwethers of the system, the perverse canaries in the coal mine of plutocratic society. Of course, we must allow here for the fact that such people’s behaviour does not strike them as unseemly.

When the asshole is comprehensively reified—or when EED is well advanced—there is little sense on his own part that there is anything wrong with the picture except that he’s still waiting for that damn martini. Did you send down the street for it, or what? Such blindness is part of the true asshole. The jerk, again by contrast, may come to perceive that his behaviour has been bad, that he has failed his fellow citizens in not treating them as peers. This may happen soon after the behaviour, especially when the immediate circumstances change (I get that cool drink, we get out of the small car, the air clears); or perhaps when, relating the event to a friend in search of validation, he instead receives a rebuke.

Regret may be rare and hard to come by, but the general sense that jerkiness is associated with perceived and maybe temporary superiority, rather than with entrenched entitlement, offers at least the chance of asking oneself: Hey, was I being a jerk? (With Schwitzgebel, I will forgo the overly optimistic claim that one might come to this realization in the midst of the situation. This is too much to hope for: even saints have bad days.)

In short, there is a democratic republic of jerks, and we are all potential citizens of it. “No one is a perfect jerk or a perfect sweetheart,” Schwitzgebel notes; but we can recognize salient features and common triggers. Jerkiness, like assholery, tends to rise in prospect as one ascends in a social hierarchy: it becomes easier to indulge jerky impulses where there are more perceived underlings. For obvious reasons, jerks tend to deploy their bad behaviour down the social scale, even while (sometimes) affecting sweetness on the upside. Thus servers, clerks, students, cashiers, and—especially—strangers can be seen as easy targets. Without fear of reprisal or loss of status, indeed with a sense of confirming it by getting one’s way or securing an advantage, jerkiness can seem justified.

This leads, in turn, to hypocrisy: the shortcomings of others are clear and distinct while mine are forgivable and even justified. Two old bits of everyday wisdom capture the essence of the democratic republic of jerks. First, when I am driving on a highway, there are three kinds of people: the ones going slower than me (idiots), the ones going faster than me (assholes), and the one going the appropriate speed (me). And second, you can always tell what people are like by how they treat waiters. (Hints: sometimes it’s the kitchen’s fault; it’s a harder job than you’d think; and it wouldn’t kill you to tip well.)

And so we might say that, when it comes to the jerk within, eternal vigilance is the price of civility. But is there more to be said about the political dimension of such behaviour, something that Schwitzgebel neglects? James, for his part, makes the obvious point that the core issue is economic in a section of his book, called “Asshole Capitalism.” Unlike authoritarian or aristocratic regimes, in which a small group of assholes rules over the rest of us, capitalist regimes ostensibly organized according to democratic principles allow a value-free and allegedly meritocratic regime in which a fluid number of assholes can game the entire system in their favour. The pocketing government and banking systems flow naturally as a rational extension of taking one’s proper advantage. Capito-democracy, as I call it, is essentially a customer-loyalty program skewed in favour of asshole elites.

So let us consider for a moment what it means to live in an alleged democracy that is, in many ways, a highly segregated, positional, and hierarchical society. Much of that structural status is, as I’ve already suggested, driven by wealth. But that is not the entire range of the problem. Can we animate in this land a sense of what the political theorist Raymond Geuss has called the “generalized nemesis” ? That is to say, the lived reality that no one really is, in an important sense, superior to anyone else—that all claims to superiority are inherently suspect?

In the modern jerk republic, real democracy is a fugitive undertaking, always fleeing its own institutional failures and the trapdoors of privilege. Its abstract promise of equality must be renewed, again and again, as a gift—a gift we give to one another but also, more importantly, to ourselves. Join me now, fellow citizens, and confront the jerk who may dwell inside you. In the gift economy of lived democracy, where everybody is at least as good as everybody else, we can all be winners.

Excerpted from Measure Yourself Against the Earth (Biblioasis, 2015), by Mark Kingwell.

This appeared in the January/February 2016 issue.