He stands on stage, dressed in a black T-shirt, denim jacket, and jeans. Holding a microphone, his remarks are relaxed, precise, biting. He is in complete control of the crowd. “How do you accidentally let in a Nazi to the Parliament? How does that happen?” he riffs, referring to the Nazi-linked former soldier who ended up being invited to Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s visit to Canada in 2023. “Should we do a background check?”—he is now impersonating two Liberal bureaucrats chatting—“No, no, no. You just tell Adolf to be on time.”

A political gaffe one Jewish human rights group called “beyond outrageous”—the vet ended up being cheered as a hero in the House of Commons—might not be what most comedians would mine for laughs. But then there’s very little Sugar Sammy won’t ridicule.

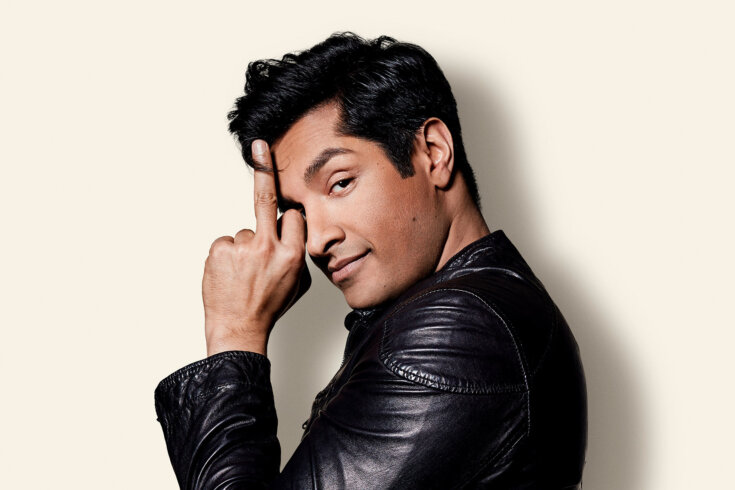

Sammy, born Samir Khullar, is one of the most sought-after comics in the world. As a student at McGill University, he started promoting clubs and throwing parties to pay off his tuition while perfecting his barb-laden act at comedy clubs and open-mic nights. His break-out moment happened in 2004, when he secured a spot at the Just for Laughs comedy festival in Montreal. He’s since performed over 1,900 shows in more than thirty countries in four languages. His 2012 tour, You’re Gonna Rire, was the first major comedy show in Quebec to seamlessly blend both English and French. Grossing over $17 million, it remains the best-selling comedy debut in the province’s history. Sammy’s multilingual wit has also made him a household name in France, with him appearing as one of the judges on the French version of America’s Got Talent. In 2017, a GQ France headline declared “the funniest man in France is a Quebecer.”

Sammy’s success can be boiled down to one thing: banter. The best parts of his shows, the parts that make up the vast majority of his clips on YouTube and TikTok, aren’t scripted. A master of observational comedy, Sammy scans his audiences and—whether he’s in Paris, Dallas, or Moncton—promptly finds someone to needle. Nothing’s off limits. Relationships, immigration, American politics? He’s your man. “I don’t think Trump won, I think Hillary lost,” he told a crowd in Illinois. “I don’t think America was ready to elect a woman. That’s too much progress for this country. You just had a Black president before. You can’t go from Black to woman in this country. You need a KKK break in the middle.”

Back home in Quebec, Sammy reserves his most devastating fusillade of jibes and taunts for the province’s sovereigntist movement and its linguistic zealots. He routinely mocks Quebec’s language laws, especially when they cross into reactionary panic. “For Christmas, I’d like a complaint from the Office de la langue française,” announced an English-only billboard in 2014, defying the provincial agency that enforces how French is spoken and written. The marketing stunt promptly drew the ire of columnists and, yes, an official complaint from a Montreal lawyer. More recently, when Quebec announced all economic immigrants would be forced to pass a French test before arriving, Sammy was quick to bring up the province’s high illiteracy rates and the fact that many immigrants speak impeccable French. “Let me tell you something. If they gave that test to all of Quebec to see who could stay, 80 percent of this province would be empty,” he said. “It’s just going to be a bunch of Algerians and Moroccans. They’ll rename the place Quebeckistan.”

Quebec ethnic nationalists aren’t laughing. Conservative pundit Mathieu Bock-Côté referred to Sammy’s Quebec fans as “psychologically flawed.” Bock-Côté wrote, “If Sugar Sammy is the future of Quebec, then Quebec has no future.” Sammy has been accused of stoking Francophobia (even though he routinely performs in French and openly states he loves the language and believes in its protection) and has even received death threats.

Sammy is a product of his environment. As the child of immigrants, immersed in Montreal’s multicultural neighbourhood of Côte-des-Neiges, he grew up speaking his parents’ maternal languages (Hindi and Punjabi), English with friends, and French at school—as required by Quebec’s Bill 101 language law. His upbringing gave him not only the linguistic tools to perform bilingual shows effortlessly but also a deep understanding of the racism underlying ethnic stereotypes and clichés—knowledge he draws on during his stand-up. His subversive improv work includes treating people with Arabic names as terrorists and making fun of the accents of fellow Indo-Canadians. While not quite a schtick, these punchlines generate applause—and groans. Sammy gets away with it because he’s good at reading a room. When he senses he’s near a tipping point and about to lose the audience, he bursts out laughing. An easygoing, self-aware laugh that lights up his face and immediately defuses any tension. Yet the social criticism hangs in the air. That’s where the craft comes in.

Sammy has never hidden the fact that former Quebec premier Jacques Parizeau’s notorious declaration after the 1995 referendum on sovereignty, blaming the loss on “money and the ethnic vote,” made ethnic kids like him feel like they would never truly be seen as so-called “real” Quebecers. “I realized that I would always be ‘the other’ in Quebec, no matter what language I spoke,” he told the New York Times in 2018.

But, while being seen as an “other” and an outsider can be a destabilizing experience, it can be gold for a provocateur. It allows them to satirize politics and social dynamics from multiple vantage points, increasing the breadth and complexity of their observations. A favourite target is the Coalition Avenir Québec, the province’s governing party that has taken a restrictive stance on immigration. At any given moment, Sammy can shape-shift, simultaneously channelling both the majority and minority groups’ preconceived ideas and phobias about each other. It underpins his boundary-bending moments, such as when he brings up the idea of “good immigrants” from France that he says the CAQ wants versus the “bad immigrants” from Mexico they don’t. Sammy can see that—and can say it—because, like all third-culture kids, he belongs to more than one world.

In many ways, Sammy has spearheaded an entirely new generation of post–Bill 101 Quebec comedians who are reclaiming not only their plural identities but also using comedy to point out systemic racism, xenophobia, and that relentless “othering.” They include Tunisian Emna Achour, who put together a roster of local female comedians with Haitian, Latina, and Turkish origins for her show Québécoises . . . que vous le vouliez ou non (Quebecers . . . whether you like it not). There’s also Iraqi Moroccan Adib Alkhalidey and his sold-out show Québécois Tabarnak (Quebecer, God damn it!). When Alkhalidey says, “If I let my beard grow, I’ll hear nothing but Taliban jokes, but if my white friends grow beards, everyone asks them if they just got back from camping and if the trout were biting,” he’s cracking a one-liner but also pointing out a double standard. In many ways, Sammy paved the way for Quebec comedy to better represent the province’s complex, shifting reality while addressing an audience that’s also changing.

Sammy likes to brandish his homegrown cred on stage. “I’m more Quebecois than you,” he ad-libs in French with an audience member. “Not for the CAQ but definitely for Revenu Québec.” In part, he’s poking fun at tiresome culture wars. But it’s also about interacting with a francophone majority who, he says, are comfortable being teased (indeed, he draws full houses in small towns all over the province, from Saguenay to Val-d’Or). For Sammy’s allophone audience, likely exhausted by the never-ending political and ideological tensions, his shows are a form of collective therapy. A way of blowing off steam. After five years of the CAQ scapegoating immigrants, religious minorities, and the province’s English-speaking community, and with the Parti Québécois promising another referendum if elected, laughing together can provide comfort and, yes, even unity. “Humour allows you to address taboos,” the comedian once explained. “In Quebec, the ultimate taboo is identity.”

Ultimately, shared jokes imply a shared way of confronting reality and very often a shared perspective. Sammy’s “inside jokes” would bomb if both the comedian and audience weren’t part of the same group: Quebecers.