In the bustling student centre at the state university in Plattsburgh, New York, a town of 19,000 just a few kilometres south of the Quebec border, Vicky Banas stands at attention beside a table draped with the Canadian flag. On this rainy Thursday morning in late April, she and five other members of Club Canada—dedicated to promoting knowledge of the country—have laid out display boards showing images of the Plains of Abraham and plates of poutine. The group has organized a promotional trip to Quebec City. The bus leaves Saturday morning. They still have tickets left to sell.

“Drinking age is eighteen in Quebec, right? ” says a scruffy-haired guy who has approached Banas. He’s wearing flip-flops, sweatpants, and a Plattsburgh State T-shirt. So is the girl he’s with.

Banas, a round-faced junior in cat’s-eye glasses, ignores the question. “Want to answer a trivia question for a chance to win a Club Canada T-shirt? ”

“Okay.”

“What is Justin Bieber’s home province? ”

“That’s easy: Ontario,” says the guy.

“Why do you know so much about Canada? ” asks the girl.

“I don’t know about Canada. I know about Justin Bieber.”

Banas takes down his name for the T-shirt raffle. It turns out the guy has already bought a bus ticket and was just killing time around the table. “To be honest with you,” she says after he slouches away, “I think some kids just want to go on this trip so they can drink. It’s kind of lame.”

As president of the twelve-member club, she heads up a curious sleeper cell, a group devoted to Canada—but which has no Canadian members—at a university that has recently suspended one of the oldest, most comprehensive Canadian studies majors in the US. Only eight students are currently registered as majors, down from more than twenty a few years ago, and a state budget crisis has left the school struggling to support such niche disciplines.

Once Upon a Time in the Congo

A Kinshasa youth subculture derived from American mythology

Jennifer Spinner

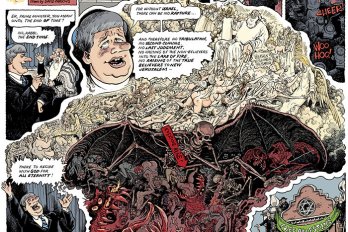

In the late ’50s, cowboys took to the streets of Léopoldville (now Kinshasa)—not the gunslingers of American lore, but Congolese teenagers in bandanas and leather boots. At the time, the Belgian Congo’s colonial education policy restricted secondary school to Europeans. In the capital, idle teens found inspiration from the likes of John Wayne and Charlton Heston at the recently opened cinemas. Calling themselves “bills” (after such cowboy heroes as Wild Bill Hickok and Buffalo Bill Cody), they staked their own territories and named them after American places like Dallas and Sante Fe, parodying Léopoldville’s segregated zoning laws (their communal residences were called “ranches”). Although known for gang violence, the bills were drawn to the cowboys’ reputed honour, bravery, and vigilantism—characteristics that resonated under Belgian rule.

—Barry Chong

“Liking Canada is definitely not something you do to be popular,” says Banas, who joined the club because an ex-boyfriend was a member. Before that, her strongest connection with Canada entailed listening to the Tragically Hip on Ontario radio stations she picked up from her native Buffalo. “Then I started to learn more about Canada,” she continues, “and everything I learned I liked. People think it’s the same as America, but it’s not. If more Americans knew about Canada, they’d love it. Like, Rick Mercer, he’s the most hilarious thing ever. And poutine. It’s everything Americans want: fries, cheese, gravy.” Not enough to make them want a trip to Quebec, though. After two hours, she packs up the display. She still has tickets left, but she’ll be late for her next class if she doesn’t hustle.

I walk across the grassy campus to a Victorian-style building to meet with David Palmieri, a lecturer in the Canadian studies department; his office is in the basement. “College students are always looking for a way to rebel,” says the self-described Québéciste about the school’s Canadaphiles (he has taught some Club Canada members but has no regular involvement with the group). “Some kids get into punk rock. Some get into Canada.” Palmieri possesses what he laughingly calls a “completely unreasonable” affection for Canada, but he doesn’t know whether he’ll still have a position with the university in September.

That evening, I meet the club in the rec room of a residence hall, where Jimmy McCartney, a hometown boy, has laid out pizzas and soft drinks for a movie night. The flick is Bon Cop, Bad Cop. Wiry and wide eyed, McCartney, a Canadian studies minor, remembers a frustrating conversation that took place in class earlier that day. The students were discussing religion, he says, but everyone was stuck in orthodox ways of thinking. He doesn’t like that. In fact, he considers himself a libertarian, and he appreciates how Canadian society encourages a multitude of opinions.

Mat Maloney, also an upstate New York native, is the club’s other libertarian. Lanky and red cheeked, he tells me his favourite politician—not just in the US but anywhere—is controversial Quebec MP Maxime Bernier, because he likes how Bernier speaks his mind. But that’s a subject for another time. Right now, Maloney is pissed off. “The flyers for movie night weren’t distributed,” he says. “I gave them to a guy in the dorm who said he’d post them, but they’re not up anywhere.” Over the course of movie night, only a few students pass through, mostly to buy drinks from the vending machine or use the microwave.

When the movie ends, I ask club member Elli Edelstein if it feels weird to be part of a group that’s been officially marginalized. “Yeah, it is strange,” she says. “But I like strange things.” She smiles easily and has wild red hair. She grew up in Alaska, where her father moved the family from Alabama to pan for gold (he didn’t find any). Now she lives behind a TV repair shop with her fiancé, Dan; a rabbit; and five small rodents called cavies. She says she’s into Canada because the government cares about its citizens more than the United States does—and because Canadian companies make the best vegan products. “Daiya in BC has this fake cheese,” she says. “It’s as addictive as crack.” When I ask about her politics, she shows me her Socialist Party membership card.

Back at the student centre the next morning for another round of table duty, Banas mentions that she’s registered with the Green Party. Ted Doherty, the club’s treasurer, says it’s bullshit that gay marriage isn’t legal in every state, and thinks Canadian men aren’t as concerned as American ones about being macho. A gregarious, curly-haired member named Donna Kelly says she has a sister who doesn’t feel as if she can be herself in this part of the state, but is okay wearing a rainbow belt on visits to Kingston, Ontario.

Two hours pass. The trip finally sells out.

On Friday night, I meet Banas, Doherty, Kelly, and Edelstein at Monopole, the oldest bar in Plattsburgh. We drink Saranac beer, and some of us do tequila shots. Edelstein does neither—she’s newly pregnant, with a boy. “We need to figure out a way to get him born in Canada,” she says. “Then we’ll get Dan’s parents to retire and buy a place in Nova Scotia and move in. Is that weird? ” She shrugs. “If it is, I don’t care.” At that, everyone raises a glass.

This appeared in the October 2011 issue.