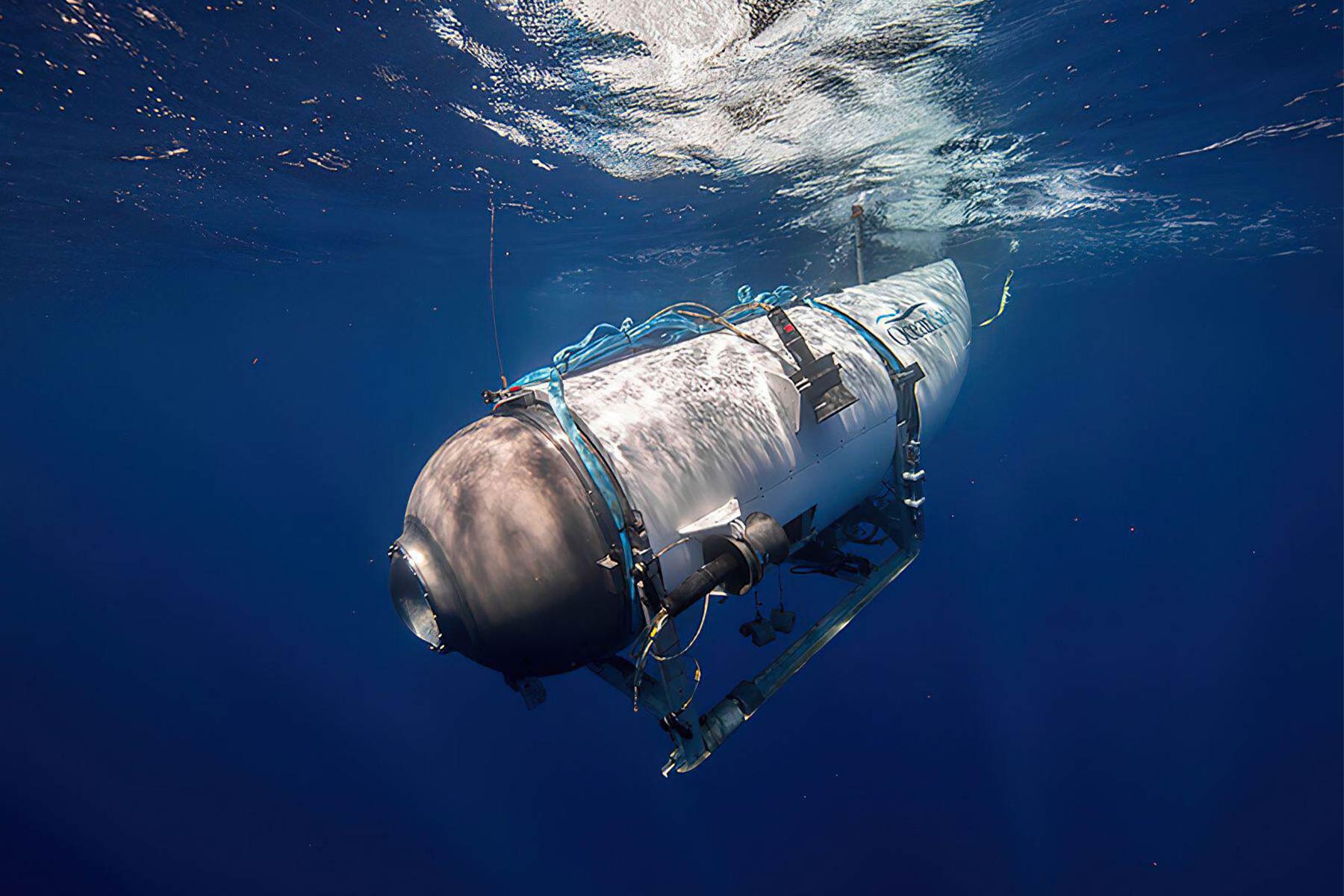

On Sunday, June 18, a tourist submersible carrying five people to the wreckage of the Titanic disappeared in the North Atlantic. Five days later, a costly search—involving ships, planes, sonar, and a remotely operated vehicle (ROV)—revealed that the Titan had imploded, scattering debris on the ocean floor and killing everyone on board. The media’s focus centred on OceanGate Expeditions and its overly confident CEO, Stockton Rush, whose obsession with building a SpaceX for the ocean led to flouting of industry standards and regulations and a submersible built with off-the-shelf parts, including a now-notorious video game controller. However, a curious Newfoundland connection evaded scrutiny.

In the months leading up to the accident, the Memorial University of Newfoundland’s Marine Institute, based in the provincial capital of St. John’s, announced in the MUN Gazette, the university’s official news site, that it had partnered with OceanGate to provide it access to its facilities and students. “Our partnership with OceanGate expands the opportunities for our students to participate in ocean exploration and gain hands-on experience by supporting the pre-departure preparation and through on-shore and sea-based work-terms,” Angie Clarke, associate vice-president of academic and student affairs at the Marine Institute, is quoted in the announcement. “These expeditions provide students with insight into both history and their own futures in the ocean technology field as they support the dive teams and OceanGate’s use of deep-sea technology.” An MUN student was working on board Titan’s mother ship, the Polar Prince, when radio contact with the submersible was lost and it imploded. How could Canada’s premier ocean-technology institute, staffed by engineers and technicians trained in the exact fields where OceanGate had failed so prodigiously, miss the warning signs?

Based on the US West Coast, in Everett, Washington, OceanGate Expeditions faced a logistical challenge setting up a deep-diving operation on the East Coast: How to ship its equipment back and forth after the summer diving season? Partnering with Newfoundlanders allowed the company to avoid such an expensive hassle and gain valuable community support and expertise. MUN’s Marine Institute was the logical choice. Its St. John’s campus is a nautical hub, with work labs and storage space as well as a wharf for launching vessels. The institute is also home to simulators that can recreate all sorts of imaginable situations at sea, such as piloting vehicles underwater, docking and loading ships, maintaining an engine room, launching lifeboats, and navigating at sea in a spectrum of conditions. The bridge simulator can even recreate the Titanic ’s collision with an iceberg, as a Guardian journalist did when he visited the Marine Institute in 2012.

Ever since the storied shipwreck was discovered over 600 kilometres off Newfoundland’s coast in 1985, St. John’s has become the launching point for all Titanic-related expeditions: some big, some small, some noble, some less so. Scavengers, archaeologists, scientists, film directors, and tourists begin their journeys to the Titanic from the St. John’s harbour. Last February, OceanGate’s Titan arrived at the Marine Institute. “Everyone’s super excited about it,” Joe Singleton, the institute’s interim head, told the CBC in May in an interview about the newly announced partnership. Over the following months, the Titan would sit in the same lab where students learned how to maintain underwater vehicles. Singleton said that as Rush became well acquainted with the students, he would be the one who would get to decide which students might get to join the expedition on the support vessel. “If maybe one of the expedition members got cold feet and they felt like they didn’t want to go . . . [the student] might get an actual seat on the dive,” Singleton told the CBC hypothetically, although there was no plan to place a student on the Titan itself.

The night the Titan went missing, a marine contractor based out of North West River, Labrador, got a call about an emergency offshore job. Michael Hannaford earned two distance degrees at the Marine Institute: a bachelor of technology and a master of marine spatial planning. Today, he works as a marine planner in Labrador and occasionally pilots ROVs on research expeditions. Two days after the call, Hannaford joined a search-and-rescue team gearing up on a ship docked at the St. John’s harbour. Even though he knew the chances of finding someone alive were slim, he remembers the atmosphere on board being focused and busy and optimistic. “Everybody functions with [the idea that] you’re going to rescue people,” he says.

In the early hours of June 21, just as the Titan neared the end of its critical ninety-six-hour oxygen supply, Hannaford and the search crew dropped an ROV into the Atlantic, and the first shift of pilots started to scour the ocean floor. Within a few hours, the crew discovered the wreckage of the Titan. Any hopes of a rescue mission evaporated quickly, and a deflated feeling settled over the crew.

During the operation, Hannaford learned about MUN’s involvement with OceanGate, including that a student was on board the support ship during the accident. “I don’t know why a marine institute would partner with a [company] that takes billionaires down to do scenic tours of a mass grave site,” he says. “I find that to actually be quite offensive. There’s no scientific value to it—none.” Hannaford also worried about MUN students being drawn in by the hope of diving to the Titanic: “They were dangerously close to getting on that stupid thing.”

In the aftermath of the implosion, MUN released a statement of condolence for the lives lost, published in the MUN Gazette. The statement, however, did not apologize for the institute’s partnering with OceanGate. Instead, it seemed to distance itself from a collaboration that it had celebrated only a few months earlier: “No Marine Institute employees or students travelled onboard the Titan. However, one student accepted summer employment with OceanGate and was aboard the support ship, MV Polar Prince, which initially launched the Titan,” read the statement. (Joe Singleton declined an interview. Despite MUN previously calling the relationship between its Marine Institute and OceanGate a “partnership,” spokesperson Kimberly Thornhill recently told The Walrus that the “Marine Institute did not partner with OceanGate, beyond providing storage and workshop space.”)

To be fair, the Marine Institute was not the only reputable name attached to OceanGate Expeditions. A retired United States Coast Guard rear admiral sat on the company’s board. And Paul-Henri Nargeolet, the French submariner and Titanic expert who died on board the Titan, was a beloved figure within the ocean-exploration world. OceanGate also sought out big-name backers to condone its “innovative” approach, according to The New Yorker. There is a troubling pattern among researchers and universities of coming under tremendous pressure to raise funding at a time when government support for post-secondary education is waning. MUN might have been drawn in by the sensationalism of the mission to the Titanic or by the idea of promoting maritime opportunities beyond the conventional industries of shipping, fishing, and oil and gas.

Whatever the reasons, a modicum of due diligence on MUN’s part would have exposed OceanGate as an outlier within the submersible community. In 2018, the Marine Technology Society (MTS) had penned a personal letter to Rush urging him to certify the Titan with a leading agency—advice that he ignored. (MUN and MTS are well acquainted; MTS’s current president elect trained at MUN.) Around the same time, OceanGate was suing its former director of operations for writing a damaging report about the submersible’s faulty design. (While I was writing my new book, The Deepest Map, I spent months approaching private submersible operators and deep-sea research organizations for a spot on board a sub. After they all politely declined my request, with spots taken up by either paying customers or researchers, I always asked who else I might approach. No one recommended OceanGate Expeditions, and I heard a few off-the-record warnings as well.)

MUN’s Marine Institute, despite its technical expertise and community connections, had no apparent concerns over a partnership with OceanGate and granted the company access to its students. Perhaps the university was simply captivated by the swashbuckling Stockton Rush and the sensationalism of diving to the Titanic—enough to ignore the dubious ethics and scientific value of charging passengers to visit the same tragic shipwreck again and again. “I don’t know if it diminishes me or my program or anything like that,” Hannaford says. “But it certainly diminishes the institute—as a marine science-, technology-, and industry-driven place that couldn’t see this operation for what it was.”