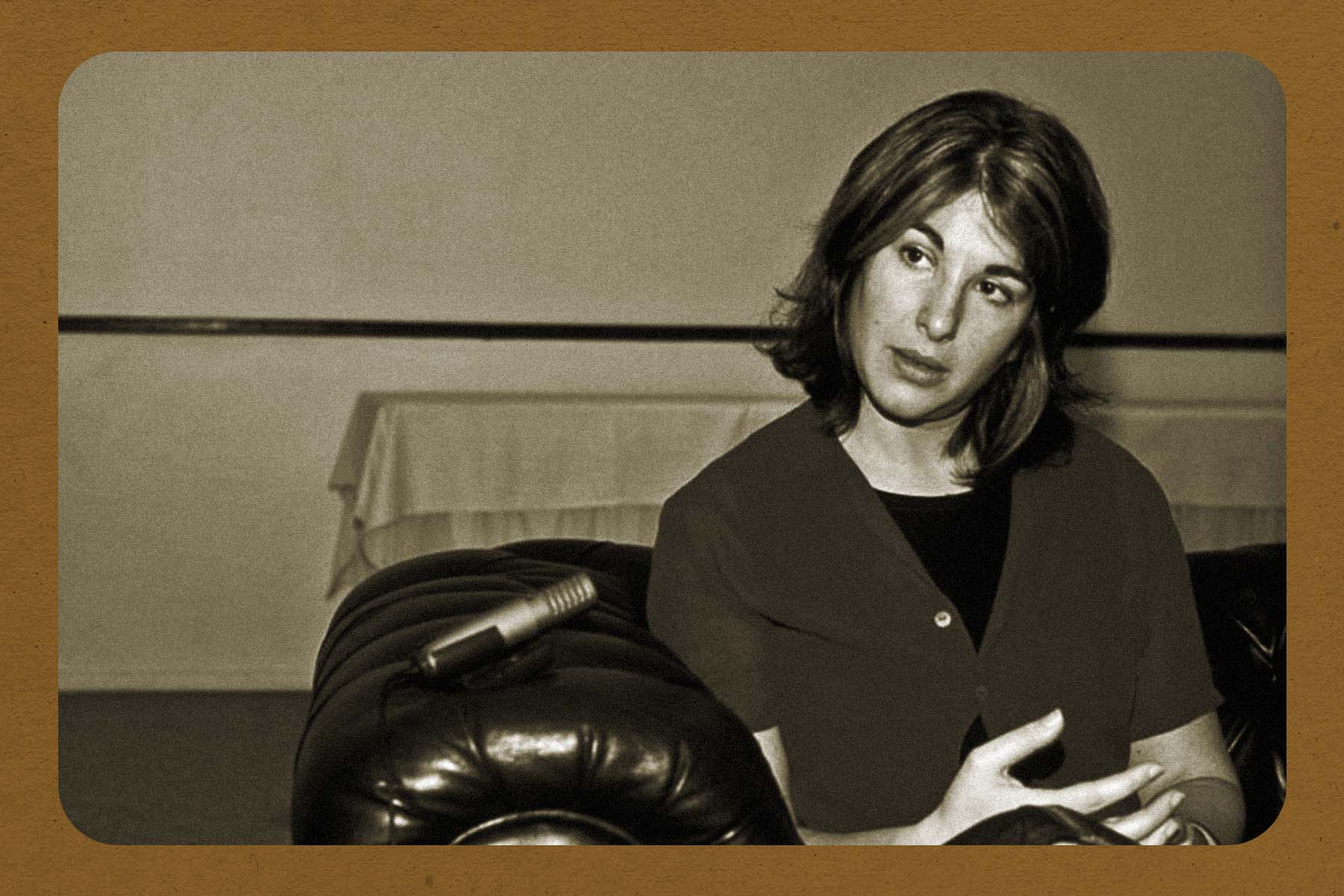

Iwas nervous to speak with Naomi Klein. For twenty-five years, she has shown an unfailing, unflagging ability to understand the invisible structures which scaffold our world and which skew it away from justice. As a writer, speaker, thinker, and organizer, she has led a struggle against greed in its many forms, but her new book casts her gaze in a new direction: into the mirror. Doppelganger is an examination of conservative populism, vaccine skepticism, “wellness” flimflam, social media wish fulfillment, antisemitism, Zionism—and Klein’s “big-haired” mirror image, the commentator Naomi Wolf. It’s also a frank, and at times vulnerable, consideration of ego. What would Klein observe in me, I wondered. What arrogance, artifice, or deception?

But when the time came and Klein picked up the phone, the conversation we had was warm, far reaching, and easy. Toward the end, I found myself contrasting our respective practices: “I’m a fiction writer, asking questions,” I said. “You’re a nonfiction writer, seeking answers.” She didn’t quite agree with the characterization. As she talked to me, patiently, about complicity and introspection, I realized: we’re both just trying to find new ways to see.

Sean Michaels: So. My name is Sean Michaels. And you probably don’t know this, but there are two other prominent Sean Michaels. One is a professional wrestler [whose first name is spelled Shawn], and he’s been famous since I was a kid. There’s also a porn star called Sean Michaels, who has made my internet life complicated for twenty years.

Naomi Klein: Amazing. Is this why The Walrus asked you to talk to me?

SM: Maybe! I think what I’ve learned from those two other Sean Michaels is one of the lessons that you get around to in the book—this idea of finding a way to de-centre yourself and let go of a certain kind of individualism. And so I wondered: How is that de-centring of yourself going, especially in book promotion season?

NK: Yeah, it’s full of contradictions. I really do sincerely believe that there is something profound we can learn from the experience of being confused with others. And it’s a particularly common experience, I think, for racialized people, who get confused with other racialized people just because they’re co-workers. There’s a kind of white supremacy that breaks our brains, right?

One of the reasons that I wanted to write this book is that I wanted to find my way back to some of the material I wrote about in my first book, No Logo. The landscape has changed so much since I first started writing about personal branding in the ’90s. There are threads in the book around the doubling of the self and the self taking up too much space. Even having kids is a form of doubling the self. I think this has such a deep impact on how we relate to each other, how we’re able to trust social movements. I really believe that we are not going to get out of any of the messes we’re in until we can find ways to work more robustly with others and in collective spaces. Anything that softens the icy edges of identity, melts them a little bit, is going to be helpful in that. Doppelgangers do that. They force you to reckon with the fact that maybe we aren’t as unique as we might believe. Being confused with someone else can be liberating.

Your question around book promotion is interesting. I’m in a very different gear than I was in writing the book, when I was wearing the self more lightly, genuinely taking myself less seriously than I have in the past twenty years. I had fun when I was writing No Logo. When the book came out, I became known very widely and very quickly. I had only just turned thirty, but I very quickly felt the weight of the left on my shoulders. That book made me the face of a certain kind of political movement. The next books—The Shock Doctrine or This Changes Everything—were exercises in a more serious and austere kind of writing. I don’t want to throw those books under the bus; I’m proud of that work. But I wanted to find my way back to that space of “Who cares?” With book promotion, you’re supposed to take yourself very seriously. I’m trying not to, as you can tell, from this rambling answer. My publisher keeps trying to get me to give more succinct answers.

SM: In the book, you argue against individualism and a certain kind of existential arrogance. But it must be hard to rally against celebrity while also being a public figure. Do you feel that tension?

NK: It’s definitely weird. You write a book, you want people to read it, and that does mean that you’re out there in the culture going, “Look at me!”—trying to get above the roar of Trump’s mugshots and so on. But I’ve always lived with contradictions. Writing is such a solitary practice, and book promotion is the opposite. I think it’s partly why writers are always going to be interested in the dualism of the self, because the two main activities that are expected of you are so completely opposite: “Be alone in this room in your pajamas for a few years with your own ideas and thoughts, and then go and perform this totally different personality.” You have to be hyper aware of the idea that we do contain multitudes.

Were you embarrassed by the other Seans? Or were you interested in them?

SM: I was usually embarrassed. So often, when I hand over my credit card to somebody, they see my name and make a joke. And I can’t tell if it’s about pornography or wrestling. But it’s also brought up vanity for me. I’ve found myself wanting to be the first Sean Michaels to come up on Wikipedia. It creates this arbitrary competitiveness with a complete stranger. I felt a jolt of recognition reading what you wrote in Doppelganger about your frustration with being confused with Naomi Wolf [the feminist author turned conspiracy theorist]. You describe Wolf’s politics as being as if she had taken your ideas and fed them through a “bonkers blender.” Whereas I had a realization, at some point in my fiction-writing career, that no matter what my intentions are, each reader is reading my ideas through their own bonkers blender. And I have no control over being misunderstood. Every one of my books is misunderstood, to some degree.

NK: You can be misunderstood or more deeply understood than even you understand yourself, right? It’s both good and bad, the fact that people bring their own brains to your book. I’m sure you have conversations where people see things that you didn’t see. And that is the fun part of what we’re calling book promotion. It’s also having conversations like this one, where you talk to other writers and actually have new ideas, see things you didn’t see before. It’s wonderful. But you can’t take responsibility for those ideas either; those are other people’s great ideas. You can be enriched by them, but you’re not responsible for them, just as you’re not responsible for people distorting your ideas. And I’m not accusing [Wolf] of plagiarism. I’m not saying she’s doing this on purpose. It’s just that that’s the way it feels to me.

SM: Reading the book, I felt sad that your attempts to get in touch with Naomi Wolf were unsuccessful. How are you sitting with your emotions around that non-relationship at this moment?

NK: I think it speaks to the decisiveness of her departure from her old self. To me, maybe the most interesting thing about Naomi Wolf is not that she’s a doppelganger of me but that she’s a doppelganger of herself. That she has changed so dramatically from the persona and community that she used to be a part of. I write for the Guardian, a publication she used to write for that she often seems to believe is not worth engaging with in any way whatsoever—the way I feel about someone like Tucker Carlson. So in terms of whether I feel sad about that . . . I think a conversation wouldn’t be possible at this point.

SM: Like you, I grew up in a Jewish household. When I was reading the book, I wrote down “wow” in the margins when you pivoted to talking about Israel. You brought up a conversation that you could easily have dodged, as most anti-Zionist Jews, like myself, spend much of our lives doing.

NK: Yeah, there were a couple people who thought I should cut it back—and it would have definitely been a tighter book. But interrogating that and answering those suggestions made me realize that [Israel] was a huge part of the reason I wanted to write this book, even though I knew it was going to be challenging. A book about doppelgangers has to end up being not about the other but about you. There are going to be liberal readers who nod along in the early chapters about Steve Bannon, or about Naomi Wolf palling around with Tucker Carlson, and feel a little bit safe and smug about it. The material about settler colonialism, and then Israel–Palestine, may make them much more uncomfortable. Even the section around the way we can treat children as our mini mirrors and extensions of our egos may sit uncomfortably with some liberal readers. It would have been a total failure of a book if it didn’t make “our” side feel uncomfortable. I’ve learned about myself from watching Naomi Wolf; I’ve learned about the parts of myself I want to be most wary of and attuned to. She’s been that for me, and I hope that the book can serve that role for readers.

SM: I was talking to my partner about the book and reflecting on the way that you gave yourself these tasks of finding answers to problems, which I think you achieve surprisingly often. Sometimes I think that my work as a fiction writer is not at all about answers; it’s just about posing questions. It made me wonder: “Oh, am I not accepting a big enough challenge?”

NK: This book came out of a period of not wanting to write another book. After This Changes Everything [about climate change] came out in 2014, I found myself in front of a lot of rooms where I was rallying the troops, saying, “We can do this! We’ve got a decade, here’s the PowerPoint presentation . . . ” It was much more a kind of programmatic mode. It seemed obvious that the pandemic could have been a wake-up call, where we decided that we were going to learn some really key lessons about the mistreatment of the people who hold the world up, about how we had been neglecting our elders, the importance of time in nature, the fact that we didn’t miss shopping as much as we missed each other, the importance of live art . . . ” There’s so many lessons we could have taken. But as the momentum of “normal” started descending, I started feeling kind of speechless, and I wanted to write in a more introspective and self-critical way. There is a tradition, in moments of a setback, where left-wing writers pause to ask, “Okay, what did we do wrong?” That tradition isn’t very alive right now in North America, because we’re expected to always just barrel forward and move on to the next thing and not admit that the last thing didn’t work out the way we thought it would.

SM: One of the sources of power in this book is your willingness to dip into a real vulnerability. You write about managing an online identity, about neurodivergence, your “Jewish shadow,” and even your personal encounters with Wolf. I wonder how that feels now that the book is arriving on shelves and into readers’ hands. Does that fill you with dread or a kind of relief?

NK: I feel relieved not to have to perform perfection in a way I used to think I needed to, whether that was true or not. The book asks a lot of people, in terms of looking at the hard parts of ourselves. And I don’t think it’s fair to ask that if one isn’t willing to lead by example. In No Logo, I talk about how much I loved logos, how as a kid I wanted to climb into my television set and live there, and how I wanted to touch the shiny, bulbous Shell logo. I was raised by parents who grew up in the ’60s as radicals and then had kids in the ’80s. I know what it feels like to be judged, to have your whole culture be considered trash by people who think they’re better than you. I didn’t much like that as a kid, and I don’t think it’s a very effective way of doing cultural criticism. I think you have to implicate yourself if you want people to hear you, and I am implicated in this book.