Canada exists for no natural reason

Let’s begin with an obvious fact no one will admit: Canadians and Americans are more or less the same people. A Torontonian in New York does not stick out, while a Kentuckian well might. Neither does a resident of Medicine Hat, Alberta, feel out of place in Butte, Montana, though a Vancouverite definitely would. Which is not to say that no significant differences exist between Canadians and Americans—just that our shared national border, unlike those of Europe, was not shaped by linguistic and ethnic variations. The War of 1812 made all the difference here. A complicated and unpleasant struggle, mostly forgotten, sundered our two countries. And that struggle is now 200 years old, which makes this as good a time as any to start remembering.

Major General Sir Isaac Brock

He was born on October 6, 1769, to an upper-class family from the Channel Island of Guernsey. Although he purchased each of his ranks, except for his captaincy, his tactical brilliance and empathy drew praise from his superior officers. Brock was assigned to Canada in 1802, but he disliked the colony. He regarded it as a backwater and would have rather been fighting, and dining, in Europe.

He played a primarily administrative role in Montreal, until the governor general, Sir George Prevost, appointed him Upper Canada’s military leader and acting lieutenant-governor, in 1811. Brock’s defining moment, the battle of Queenston Heights, took place on October 13, 1812. With his captains busy commanding the grenadiers, he led the charge against American forces embedded atop the Niagara Escarpment. The general was shot in the chest at close range, and died on a battlefield just north of Niagara Falls.

But Brock lives on across the country—most of which wasn’t even part of Canada when he was alive. Consider the countless roads, towns, and institutions that bear his name: Vancouver has General Brock Elementary School; Saskatchewan has the village of Brock; Newfoundland has Brock’s Head Path. In Ottawa, steps from Parliament Hill, a bust of him can be found at the Valiants Memorial, which honours fourteen of Canada’s war heroes, three of them from the War of 1812. There, a bronze inscription quotes Virgil: “No day will ever erase you from the memory of time.”

—Barry Chong

Canada exists because of the War of 1812

Military historians generally describe the War of 1812 as a stalemate. After two and a half years of fighting, not much changed between the United States and England, nor between the United States and Canada. But the war—as much as the more decisive battle of the Plains of Abraham, the American Revolution, and the Civil War—foretold North America’s political shape, its current reality. For the US, the war confirmed its status as a sovereign state and tested the limits of manifest destiny. On this side of the border, the matter is much simpler: if we hadn’t won the War of 1812, we wouldn’t be Canadian.

Canada exists because of taxes (and tax breaks)

In a continental irony, after the revolution the new American government had to raise taxes far higher than British authorities had ever dreamt of doing, to finance the overthrow of Westminster rule. Across the border, the British suddenly realized colonists could easily grow alienated. So they lowered taxes and offered prospective settlers of Upper Canada 200 acres of free land. Loyalists and late Loyalists, followed by tax exiles and land speculators from the newly united States, quickly populated what would become the province of Ontario. Upper Canada’s settler population ballooned, from 6,000 in 1785 to 14,000 in 1791, with men and women looking for opportunities and willing to wink at their US citizenship—just as British officials willingly welcomed them back from their flirtation with liberty, without too many questions.

So in the days leading up to the war, it was optimistic but not preposterous for Representative John A. Harper of New Hampshire to predict that Canadians would greet American soldiers as liberators: “They must sigh for an affiliation with the great American family—they must at least in their hearts hail that day, which separates them from a foreign monarch, and unites them by holy and unchangeable bonds, with a nation destined to rule a continent.” They would not, after all, be invaded by a foreign people. Canadians would be brought back into the fold of American Revolutionary ideals.

What occurred two centuries ago was more or less a family feud. The Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Alan Taylor titled his 2010 survey of the conflict The Civil War of 1812—a phrase that captures the profound connection between the combatants, and the unstable relationship between the Empire and the Republic. “Brother fought brother in a borderland of mixed peoples,” he writes. Those on both sides instantly recognized, and noted, the unique horror of firing on people so like themselves.

Canada exists because of hubris

The reasons the United States invaded Canada were, and remain, contentious and unclear. Officially, residues of the revolution—unresolved issues of maritime law, military conscription, and possession of the Ohio Country—led to the declaration of war on June 18, 1812. But the unofficial reasons—the prize and the odds of success—were grubby, petty. “United States,” then as now, was something of a misnomer, and the war emerged out of squabbling between the majority Jeffersonian Republicans, who hungered for expansion, and the minority Federalists, who benefited from close economic ties with Britain. By declaring war, the Republicans intended to make the Federalists look anti-patriotic and undemocratic. Both parties, however, believed the conquest of Upper and Lower Canada would be a cakewalk. At sea, the Royal Navy, though sixty times the size of the fledging US Navy, was distracted by Napoleon’s ships; on land, nearly eight million Americans would square off against just 300,000 Canadians. In August 1812, former president Thomas Jefferson declared, “The acquisition of Canada, this year, as far as the neighborhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching.”

Canada exists because of a series of lucky breaks

The comedy of errors began immediately. Even though the United States declared war, which should have given its soldiers the advantage of surprise, a messenger carried the news to Canadian military outposts on the Niagara River before it reached the New York side. British soldiers quickly detained several important—and unsuspecting—American personages on our side of the river. The initial blunder served as a telling prequel to subsequent disasters.

Tecumseh

He belongs to a tradition of misappropriated heroes, whereby one-time enemies are whitewashed as icons of a popular history. Canadians have named streets and schools after him, and the Friends of the Tecumseh Monument are now raising $5 million to honor his legacy in Southwestern Ontario. At the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, midshipmen rally around a bronze likeness, in the aptly named Tecumseh Court, which they cover in war paint for Commissioning Week, during exams, and before they face football rivals.

In life, Tecumseh fought for the survival and continued sovereignty of the Shawnee people. Born in the Ohio Country in 1768 and killed on October 5, 1813, near Moraviantown, Upper Canada, he campaigned for a confederacy of Indigenous nations. He urged Aboriginal leaders, from the Great Lakes to Georgia, to affirm pan-tribal ownership of the land—to reject settler-imposed boundaries.

During the War of 1812, he allied with the British to fight a common enemy. As Isaac Brock declared, “A more sagacious or more gallant Warrior does not I believe exist. He was the admiration of everyone who conversed with him.” Yet British actions in the battle of the Thames were not as gallant. Despite plans to fight side by side, Major General Henry Proctor retreated, leaving Tecumseh’s vastly outnumbered men to face the Americans alone. Tecumseh’s Confederacy was overwhelmed; its leader died and, along with him, the last, best chance for Aboriginal self-governance.

—Bronwen Jervis

Canada exists because of blundering Americans

The grand view of history has traditionally offered two paths for the interpretation of events. The first imagines social trends rising up from below to sweep humanity along in their irrepressible, all-powerful waves. The other dreams of iconic figures who shape history through their own vision and will. In the case of the United States during the War of 1812, we find neither. Instead, a third way emerges: history dominated by stupidity and impulse. From the revolution to the present moment, hardly a single generation of Americans has passed without giving rise to a bona fide military genius. The Civil War alone produced half a dozen. To Canada’s good fortune, the post-revolution US Army was stacked with bunglers and officers past their prime. It might have taken Canada easily, if not for the miraculously systemic idiocy among the top brass.

Canada exists because of William Hull

Every Canadian city should build a statue to Brigadier General William Hull, because it is largely thanks to the American officer’s poor planning and cowardice that our provinces and territories do not number among a Star-Spangled constellation. Taylor describes Hull as “tall, strong, and courtly, he looked the part of a war hero, but he lacked substance, alternating an imperious manner with chronic indecision.” He drank. He bragged. His subordinates despised him. President James Madison, at Hull’s urging, made the terrible decision to divide the already weak army into three and attack Upper Canada from Detroit. If the United States had decided to strike straight at Montreal—a strategy confused by backroom dealings with a political heavyweight from Ogdensburg, New York, who didn’t want his land trampled on—it might well have been “a mere matter of marching,” as Jefferson predicted.

But Canadians can thank William Hull for much more than his dreadful advice to the president. In person, he was a military buffoon and an accidental nation maker. On July 5, 1812, he arrived in Detroit with orders to take the small town of Amherstburg, just across the river. He found the town well fortified, so he sent his men instead to the undefended settlement of Sandwich, whose inhabitants immediately fled. At Sandwich (now Windsor, Ontario), he made one of the most important pronouncements in Canadian history, declaring, “No white man found fighting by the side of an Indian will be taken prisoner. Instant destruction will be his lot.” Since every Canadian militiaman and British regular served alongside Aboriginal allies, the edict effectively promised death to any farmer or shopkeeper who resisted invasion. Then Hull allowed his soldiers to plunder homes, shops, and farms, and he continued to avoid a battle at Amherstburg, even though his men outnumbered the British and Canadian troops by two to one. His cowardice proved as sizable as his malice.

Spurred on by American incompetence, the residents of Upper Canada chose to fight, where before they had been rather ambivalent and resigned to retreat. Hull squandered his military dominance and achieved the worst possible outcome. He was unnecessarily brutal, cowardly and, worst of all, totally ineffective. The major outcome of his campaign was that he left behind settlers—who may or may not have been Loyalists and late Loyalists before—who were now self-conscious possessors of a territory and a recognizable identity.

William Hull ineffectually assaulted a disparate group of people. He left behind a cohesive, distinct Canadian community.

Canada exists because of Aboriginal allies

Tecumseh was a Shawnee leader and one of the great military minds of all time. Outside the walls of Fort Detroit, he marched his men around and around, out of sight and back again, making his force appear five times larger than it was. The sleight of hand worked. Terrified, Hull liquored up and neglected his troops. The soldiers and militiamen under his command, both humiliated and scared, plotted mutiny. Major General Sir Isaac Brock, military commander and acting Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, had fewer men, and Hull held the fort. But all Brock had to do was threaten further use of Tecumseh’s force—the terror of all American soldiers. Hull’s men deserted, and he surrendered without a fight. Brock and Tecumseh were so disgusted by their opponent that they didn’t even grant him the customary honours of war.

Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Tuscaroras, Cayugas, Senecas, and other First Nations fought alongside British detachments and Canadian militias throughout the war, and they played pivotal roles at the battles of Queenston Heights, the Thames, and Stoney Creek, all up and down the Niagara Peninsula. Yet we rarely recognize this fact.

For Americans, Indians were enemies to be defeated. For Canadians, Aboriginal peoples were allies to be betrayed. As Pierre Trudeau reportedly told Marlon Brando in 1978, “There are differences in the way we treated our Natives. You hunted them down and murdered them. We starved them to death.” The contrast reveals a great deal about the War of 1812: American territorial expansion was hindered by Indigenous nations, while Canadian territorial integrity depended upon their assistance.

Richard Pierpoint

In 1760, slave traders kidnapped a teenage boy from Senegal. Sold to a British officer stationed in the Hudson River Valley, from whom he adopted his surname, Richard Pierpoint earned his freedom during the American Revolution by joining Butler’s Rangers. For his service to the Crown, the British awarded him a land grant of 200 acres along Twelve Mile Creek, in what is now St. Catharines, Ontario.

Known to his contemporaries as Captain Dick or Black Dick, Pierpoint was respected among Upper Canada’s African community as a griot (an orator and historian). When the War of 1812 began, he “proposed to raise a Corps of Men of Colour on the Niagara Frontier.” The authorities initially dismissed his proposal, but a white tavern owner eventually adopted it at Isaac Brock’s urging. Consisting of several dozen black men, the Coloured Corps defended the freedom and livelihood of Upper Canada’s African residents against American invasion, which threatened their burgeoning identity as Canadians—and as a free people.

Although the Coloured Corps underpinned British and Canadian defences throughout the Niagara Peninsula, Pierpoint did not advance beyond the rank of private. In 1821, he petitioned Lieutenant-Governor Sir Peregrine Maitland for passage to his native Senegal; the trip home never materialized, but Pierpoint was granted 100 acres near present-day Fergus, Ontario, for his wartime service. He died there sometime before September 1838, with no family or heirs.

—Amirah El-Safty

Canada exists because of heroes

The war was full of American halfwits, but our side had Tecumseh, who helped repulse the Americans at Detroit and later died in the battle of the Thames. Our side had Isaac Brock, who was killed while urging on his troops to a key victory at Queenston Heights. Our side had Laura Secord, a Loyalist originally from Massachusetts, who saved British troops from a surprise attack in 1813. (Incidentally, she did not do so while leading a cow. Nor was she barefoot. Although we can all agree that it would have made for a better story if she had been barefoot and leading a cow.) Our side was peopled by heroes whom we do not know, or cannot remember.

Canada exists because of the burning of York

On April 27, 1813, Americans assaulted York, the lakeside capital of Upper Canada, which was later renamed Toronto. As British troops retreated, they burned the harbour’s major prize, the nearly completed sloop Sir Isaac Brock. And they ignited Fort York’s gunpowder magazine on the shores of Lake Ontario. In Capital in Flames: The American Attack on York, 1813, Robert Malcomson describes the conflagration in apocalyptic terms: “In an instant 300 barrels of black powder were vaporized and transformed into a yellow-orange-red ball of flame that erupted through the upper storey, roof and sides of the magazine, blooming up into the air like some nightmarish mushroom.” The explosion killed thirty-eight of the invaders (including Brigadier General Zebulon Pike, for whom Colorado’s Pikes Peak is named) and wounded another 222. Despite assurances to the surrendering authorities, American soldiers rampaged through York, looting its churches, libraries, and fire stations. They even burned down Upper Canada’s twin parliament buildings, claiming they had found a scalp hanging beside the ceremonial mace. (They stole the staff as spoils of war; President Franklin Delano Roosevelt eventually returned it to the Ontario legislature in 1934.)

The occupying force left the city on May 1, but Americans invaded again at the end of July. Eventually, after a series of demoralizing defeats and hollow victories, and riddled with sickness, they withdrew to their side of the border. A pattern of conquest, brutality, and retreat marked American campaigns to conquer Canada. Scuttled invasions left behind a people increasingly convinced that—despite ties of blood, language, and mutual values—they were not Americans.

Canada exists because of retribution

Retaliation for the burning of York arrived slowly, surely, and viciously. Over a year later, British forces from Bermuda sacked Washington, burning the White House and the Capitol to the ground on August 24, 1814. The British soldiers were not, as Americans remembered them from the Revolutionary War, the crew of incompetents whose dogmatism cost them the Thirteen Colonies. Nor were they Canadians, as we like to tell ourselves. Rather, this crop of British military leaders had lived through the Peninsular War, which produced one of the most battle-tested, efficient, and ruthless armies in the world.

At the beginning of the war, the US Navy was almost non-existent, with only sixteen warships. The Royal Navy had over a thousand. When confronted with such a force at home, Americans had to turn their attention away from Canada. Instead of invasion and conquest, they realized that mere survival would be hard won. On September 13, 1814, Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane sent his British fleet to level Fort McHenry, a vital defence post on Chesapeake Bay, just outside Baltimore. The battle was not much of a contest. As Walter Borneman explains in 1812: The War That Forged a Nation, “It was a matter of simple math. The range of the British mortars was 3,650 meters; the range of Fort McHenry’s cannon was 1,825 meters. All through the day and into the night, the British ships kept up their bombardment.” Above the fort, a huge American flag, nine by thirteen metres, fluttered. Aboard the hms Minden, where he was negotiating a prisoner release, the Georgetown lawyer and amateur poet Francis Scott Key saw his young country’s flag still aloft through the haze.

O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light,

What so proudly we hail’d at the twilight’s last gleaming,

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight

O’er the ramparts we watch’d were so gallantly streaming?

Despite a history overflowing with triumphs, the American national anthem celebrates a fortification that barely survived bombardment during a war nobody cares about. (And its rhythm and melody are set to those of a British drinking tune—another great irony.)

On both sides, acknowledgment of the war dwells not on the victories, but on narrowly averted defeats. Americans don’t care to remember the burning of Fort York; nor do the British celebrate themselves as the army that sacked Washington. Memorializing the War of 1812 has always meant reckoning with an embarrassing stalemate.

Canada exists because of the status quo

Before the war, colonial authorities dreamt of reconquering the Crown’s lost colonies, of reuniting unruly Americans with the family of British subjects. Most prominently, John Graves Simcoe, first Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada and the founder of York, hoped to reverse the Revolutionary War. He modelled Upper Canada as a reprimand to rebellious colonists: “The establishment of the British Constitution in this Province offers the best method gradually to counteract, and ultimately to destroy or to disarm the American spirit of democratic subversion.” The battle of New Orleans, the war’s final major engagement, spelled an end to any such vision.

Troops converged downriver from New Orleans, two weeks after the Treaty of Ghent had effectively ended the war on Christmas Eve 1814. Not realizing that negotiations in Europe had affirmed the status quo ante bellum, British officers marched their men across the plain at Chalmette, Louisiana, on January 8, 1815. American troops waited behind mud ramparts, and annihilated the enemy with volley after volley of cannon and gunfire. The attack ended in disarray: nearly 300 British killed, 1,260 wounded, and 484 captured. The American force, under the command of Major General Andrew Jackson, suffered minor casualties: thirteen dead, thirty-nine wounded, and nineteen missing. The legend of Old Hickory—Tecumseh’s former adversary, the architect of New Orleans’ defence, and a future president—was born, with all its bloody consequences for Spanish Florida and for American Indians everywhere.

Before the battle of New Orleans, many Britons would have agreed with the Times of London that British generals should press their advantage in the United States: “We should grapple with a young lion when he is first fleshed with the taste of our flock than await until in the maturity of his strength he bears away at once both sheep and shepherd.” After their forces were routed, such condescension vanished.

Laura Ingersoll Secord

Popular history has distilled our most iconic war heroine’s life down to a vignette of a woman trekking through the woods on a midsummer’s eve. While tending to her husband, a Canadian militiaman wounded at the battle of Queenston Heights, Secord learned of American plans to ambush the Forty-Ninth Regiment at Beaver Dams. Aided by Aboriginal scouts, she travelled twenty miles to warn Lieutenant James FitzGibbon and his men, who were camped near present-day Thorold, Ontario.

Her bravery helped save the Forty-Ninth Regiment, but the battle of Beaver Dam itself constitutes little more than a historical footnote. Ironically, her service to the military eventually eclipsed that of FitzGibbon and his regiment: without firing a single shot, she became a bona fide war hero. In 1860, Edward Albert, Prince of Wales, dedicated Isaac Brock’s cenotaph near her family homestead, and she joined local veterans in welcoming the future Edward VII. Moved by her story, he rewarded the eighty-five-year-old Secord with £100. Lieutenant FitzGibbon, meanwhile, died penniless in 1863.

Despite her legacy, her grandson James remembered that she “did not care to have her exploit mentioned, as she did not think she had done anything extraordinary.” Nonetheless, her twenty-mile walk has become a malleable symbol: of loyalty to the Crown; of a distinct national identity; of our keener desire to lend a hand; and of a trademark box of chocolates (after the eponymous confectionary company’s founding in 1913).

—Julie Baldassi

Canada exists because of a strained friendship

In The Civil War of 1812, Alan Taylor describes a meal held in Kingston, Upper Canada, after the announcement of peace. American officers came over to inform their Canadian counterparts that the war was over, and the Canadians invited them to dinner. A band played “Yankee Doodle,” while both sides drank to the president’s health. As one officer recalled, everyone rejoiced at the end of “a hot and unnatural war between kindred peoples.”

All the stupidity and brutality of the conflict resulted in a subtle distinction: Canadians and Americans were no longer kin but kindred, no longer family members with unresolved issues but separate peoples who were like family. That nuance is vital: it’s why there is a Canada and a United States.

Canada exists because of a story that is hard to tell

There are many reasons why neither side cares to tell the story of the War of 1812. It doesn’t fit America’s ideals of itself, casting founding heroes like Jefferson and Madison as bellicose fools, and showing the United States at its worst: woefully incompetent. For us, the war doesn’t fit the victimology that has nestled comfortably at the heart of Canadian nationalism since the 1960s. Far from identifying Canadians as “beautiful losers,” the War of 1812 casts us as rather nasty fighters with a vengeful streak.

Canada exists because of a forgotten war

By accident, as if history were taking poetic licence, many of the war’s battlefields have been written over with blighted cityscapes. A tour of these urban palimpsests reads as a survey of North American decay: Detroit, Baltimore, Buffalo, New Orleans, and Hamilton. History is full of forgotten wars, but few have been so utterly erased as the War of 1812, which provokes a particularly destructive strain of cultural amnesia.

Canadians have had a vexed relationship with the War of 1812 from the beginning. Less than thirty years later, William Lyon Mackenzie must have grown tired of the Sir Isaac Brock monument that loomed behind his print shop in Queenston, because after he mounted his Upper Canada Rebellion, one of his fellow rousers belatedly blew up the original Tuscan column. Gunpowder is no longer used, but memories of the war continue to be blotted out by asphalt parking lots, strip clubs, and Money Marts—look no farther than Lundy’s Lane in Niagara Falls.

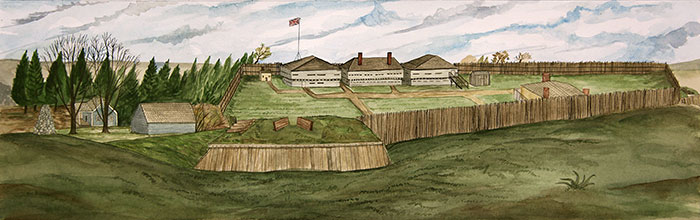

Then there’s Fort York. Last May, Toronto City Council scrapped an acclaimed design for a footbridge that would have crossed a CN rail corridor and linked the Liberty Village neighbourhood with the fort, and an award-winning historical centre soon to be built near the crumbling Gardiner Expressway. (A more parsimonious bridge design is now being considered.) Even a city burned to the ground during the War of 1812, many of whose street names derive from figures who fought on both sides, a city whose existence was shaped more by the War of 1812 than by any other event, struggles to remember.

Fort York houses the single largest collection of original buildings from the war, and it falls under local, not federal, jurisdiction. Unlike Halifax’s Citadel, or Fort George in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario—both administered by Parks Canada—Fort York is a National Historic Site maintained by an underfunded municipal agency and a charitable foundation that must overcome general apathy toward the War of 1812. The public mostly ignores the war’s forts and earthworks, which are scattered throughout our towns and cities, often right in front of us.

Canadians exist for a good reason

We generally remember our parts in other people’s history; the sites of Canadian memory tend to exist elsewhere, or remain off limits. In two world wars, the courage of our soldiers made them cannon fodder for other nations’ empires. Vimy Ridge is described as a battle that formed the Canadian identity, as is D-Day. What must be one of the largest Canadian flags anywhere flies above Juno Beach in Normandy, France. The visitor centre there offers ample public access—unlike Fort Mississauga, in the middle of a golf course in Niagara-on-the-Lake. As with most of the war’s battlefields, no Canadian flag marks that forgotten fort. As long as the Union Jack flies over War of 1812 sites here at home, we will continue to think of the conflict as a chapter of British history. While this may be true, it is even more so our history, and our flag should testify to that.

Canadian history is not as vague as we might think. Nor is it unlike those of other countries. Our national identity was born during the War of 1812—which was fought over a distinction that still resonates in provinces and territories that came into existence long after it ended. Canadians in Alberta and Yukon remain as convinced as anyone in Ontario or Quebec that they are not American, a conviction that crystallized during skirmishes and campaigns on the Niagara Peninsula 200 years ago. The fact that a war decided the question may tarnish the sheen of self-righteousness Canadians love so much, but it might also draw us to a harder, clearer truth about our position in the world. No matter what military historians say, we won the War of 1812—because we fought to be ourselves.

This appeared in the March 2012 issue.