It was on a chintzy patch of street in Niagara Falls called Clifton Hill that I was first alerted to the possibility that civilization was a mistake. There, in the shadow of an enormous sculpture of Frankenstein’s monster eating a branded Burger King Whopper sandwich, my underage mind muddied on enormous schooners of beer procured with a fake ID from an adjacent Boston Pizza, I watched two other drunk loafers come to blows in that messy, soused, all-Canadian way—where they sort of thrash each other and toss out soft punches, which roll off buttery cheeks gone red with drunkenness, the brawl resolving when one combatant attempts to jersey the other by pulling his shirt over his head like they’re in a hockey fight.

A few blocks away were Niagara Falls—both the mighty Canadian-fronting Horseshoe Falls and, on the American side, the comparably piddling Bridal Veil—with their pummelling cascades of water that make you feel small and stupid. But there, on that corporate-gaudy tourist-trapping strip, were two hammered chuckleheads locked in a sloppy, disgusting pas de deux, barely punching each other for no discernible reason while wreaths of neon lights sang their ambient buzzing song and an enormous promotional monster looked on, unfeeling. I remember imagining a cabal of ancient Greeks wrapped in cloaks, all assembled, gazing into a crystal ball and, witnessing this, gulping hemlock and cutting off humanity then and there. They saw—as I, young and blitzed on big beers, saw—that we were all basically doomed.

And this is what I think of when I think of Clifton Hill.

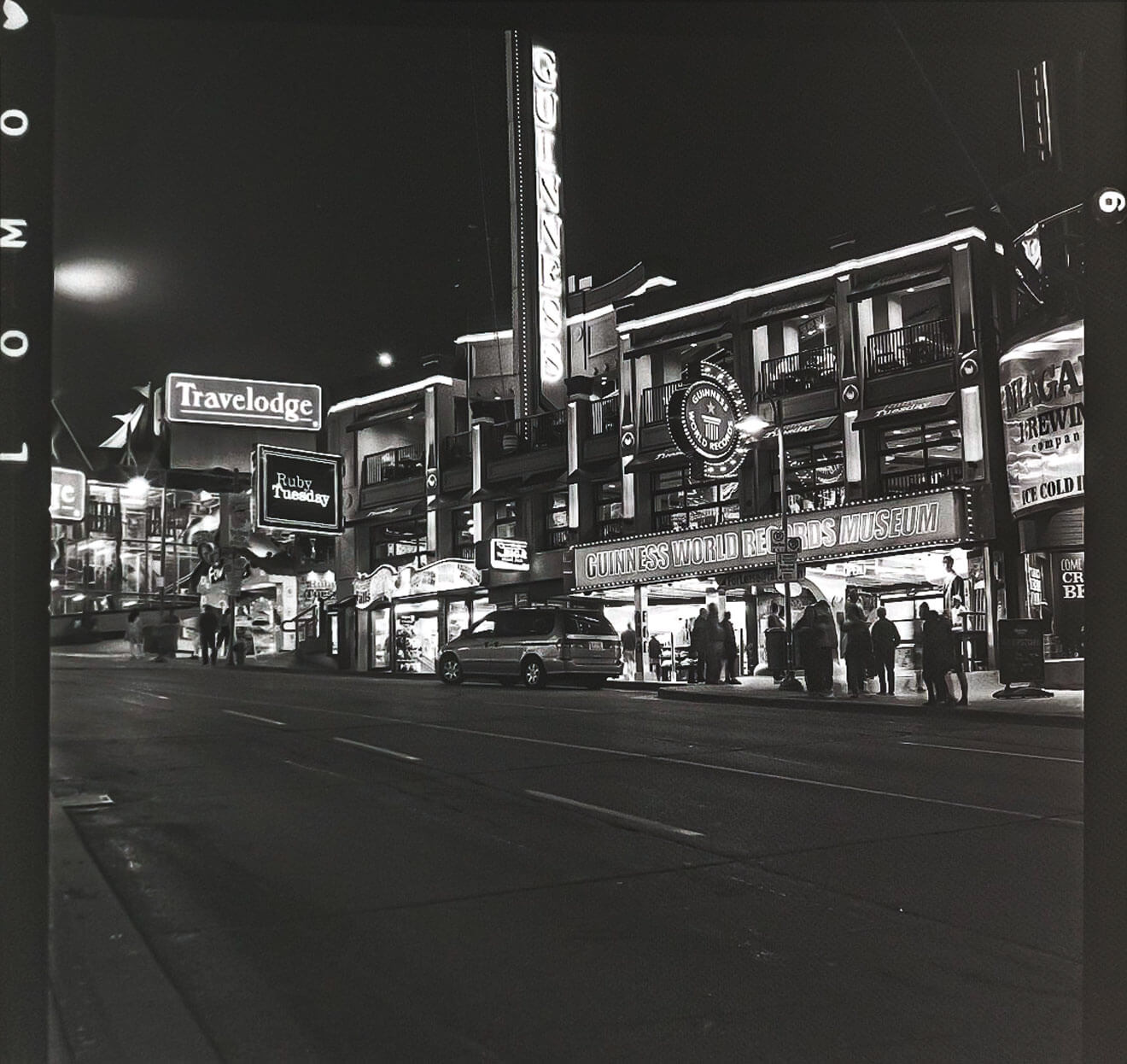

Just a block away from one of the world’s natural wonders, Clifton Hill advertises itself as a “world famous street of fun.” A stretch of road straddling Niagara Falls’ major casinos, it boasts the bulk of the town’s nonwaterfall attractions and is effectively an open-air amusement park, teeming with families, drunks, and a talking animatronic sarcophagus. It is also a walk-through allegory for Niagara Falls itself, which is a tourist town, a border town, a gambling town, a mob town, and depending on your disposition, a rather sad town. Imagine if Yellowstone had a Kelsey’s, an enormous Ferris wheel, a Skee-Ball arcade, a go-kart track, a dinosaur-themed miniature-golf course, and a mess of wax museums—a tourist district that proffers a totalizing holiday experience. The Falls’ abounding natural beauty is either complemented or affronted by these just-as-abounding man-made amusements. Again: depending on your disposition.

“It’s such a weird place,” says Canadian filmmaker Albert Shin, sitting in a sleek, modern, modular press-junket suite during the 2019 Toronto International Film Festival, where his film, Disappearance at Clifton Hill, made its world premiere (under the pithier if less evocative title Clifton Hill). “I can’t believe someone hadn’t set a film there yet.” Shin grew up around Niagara Falls, among other places. The city, and especially its tourist-baiting main drag, has long occupied his imagination. His film, which will be released in theatres at the end of February, is what one might call a poison love letter to the namesake street and the city it so awkwardly defines.

Shin’s third feature, Disappearance at Clifton Hill opens on the muddied, brown-and-tan banks of the Niagara River, where a young girl named Abby, on a fishing trip with her family, watches as a little boy is kidnapped and jammed into the trunk of an idling car. Years later, an adult Abby (played by Downton Abbey’s Tuppence Middleton) inherits her family’s Niagara Falls motor lodge—a rundown, no-tell motel with a busted sign advertising JACU ZIS POOL. A slick Clifton Hill tycoon (Eric Johnson) attempts to charm Abby into offloading the motel, which he plans to redevelop as a “glow-in-the-dark paintball maze,” but she is more interested in piecing together the mystery of the missing boy whose abduction she witnessed in her youth.

Shin’s psychodrama includes crooked Niagara Falls impresarios; scheming married French Canadian dinner theatre magicians named “The Magnificent Moulins”; and a scuba-diving podcaster—played with weirdo relish by David Cronenberg in a rare onscreen appearance—who operates out of the basement of a local diner shaped like a UFO. The location is key to the plotting, with the Clifton Hill setting taking on the role (as per the cliché) of a character.

In time, Abby’s sleuthing is compromised by emerging concerns about her mental health and the unreliability of the various narrative threads she’s weaving together in her mind. She is a liar. Or schizophrenic. Or bipolar. Or some unstable combination of the above. She has a hard time cleaving memory from imagination. She slips in and out of identities, pretending to be people she’s not.

Like Clifton Hill itself, Abby exhibits a great capacity for reinvention.

I remember coming across a photograph of my paternal grandparents posing on a Niagara Falls lookout, dressed to the nines and looking vaguely like the stars (or at least two extras) from a playful caper by Hitchcock. Even when I was a kid, the Falls’ romance seemed bygone, a shell of its exhausted ambitions. The closest I got were conspiracies about each side of Clifton Hill being owned by rival families, Montague vs. Capulet–style, or harrowing stories of nineteenth-century hotel owners sending boatfuls of wild animals over the Falls’ precipice in an early bit of carnival-barking hucksterism. The Falls were not a place to fall in love and enjoy a soak with one’s paramour but a place to be avoided, like a haunted funhouse at the bottom of a dead-end street.

Shin is quite right in noting how, despite the status of Niagara Falls as one of Canada’s key tourist destinations—welcoming an estimated 13 million visitors annually, most of whom hail from within Canada—very few films unfold there. There are a few early comedies. There’s Canadian Bacon. And there’s Henry Hathaway’s Niagara, in which Marilyn Monroe (billed as “a raging torrent of emotions that even nature can’t control!”) arranges for her jealous husband to be murdered in a tourist tunnel carved into the rock behind Horseshoe Falls. That film captures something of the honeymoon capital of the world’s midcentury idyll and invests it with the turgid intrigue of film noir.

Shot under extreme secrecy, with the misdirecting title “Jane of the Desert,” Disappearance at Clifton Hill takes a different tack. Shin reduces the roaring falls themselves to the periphery while foregrounding the infrastructure cobbled around them in all its gaudy neon and wan desperation.

“It’s always about just getting them to stay one more day,” says Shin, describing the area’s eager allure. “They come for the Falls. Then, how can they get them to stay for something else? So they built this whole thing . . . . They built stuff for children. They built stuff for adults. Casinos.” Shin’s movie elbows back against the shimmer and PR blather. As one character describes the Hill: “The haunted houses aren’t actually haunted. And the funhouses aren’t actually fun.”

Such withering appraisal didn’t exactly endear Shin’s production to the so-called city fathers. In advance of Clifton Hill’s premiere, Toronto’s Now Magazine tantalizingly described it as “the movie Niagara Falls doesn’t want you to see.”

“It is not a true—in any way, shape, or form—picture of Niagara Falls or Clifton Hill, from what I understand,” says Tim Parker of the Victoria Centre BIA, which represents business interests in the Falls area. “Clifton Hill, in any film, documentary, or context, is always put out there, for all intents and purposes, as a honky-tonk or a tourist trap—all of those slang words that obviously don’t depict Clifton Hill as it is today.”

Parker hasn’t seen Clifton Hill. His conclusions are drawn from the opinions of his colleagues who, he believes, have seen it, or have at least read early versions of the script. They’re also informed by thirty years of experience working on and around the Hill—including thirty years as the manager of the Ripley’s Believe It Or Not! Odditorium, an attraction whose “array of weird,” boasts its promotional

blather, “will leave you awe-struck.” Parker’s concern about Clifton Hill feels almost reflexive, like the result of decades of hearing people slag off what is, in his words, a “well-displayed hill of fun.”

Even before Shin’s film came along, Clifton Hill had suffered some lousy press. Last summer, the St. Catharines Standard reported on a seventeen-year-old hustler who plied his trade on Clifton Hill, nicking purses and wallets inside the Great Canadian Midway. In his statement before an Ontario court, the paper wrote, the teenager’s lawyer made shady reference to the “criminal underworld” of Niagara Falls. (People whisper about Hells Angels and “the mob” in Niagara with mischievous glints in their eyes, as if the very threat of organized criminality conferred the area with legitimacy.) Also in 2019, Vice reporter Graham Isador (a local returning in search of the city’s worst bar—a real needle-in-a-stack-of-needles quest) described Clifton Hill, accurately, as “the dark beating heart of Niagara.”

In 2014, the mockery even made international headlines, with UK tabloid the Daily Mail devoting an extensive photo gallery to “North America’s worst waxworks,” the Movielands Wax Museum of the Stars. (The story was subsequently picked up by Global News, which seemed chuffed in that deeply Canadian “Hey! People are noticing us!” way.) Pressed about that particular broadside, Parker retorts: “It’s all in the eye of the beholder. One guy could say, ‘Yep. That looks like Lucy Ball. It’s good. It’s perfect.’ And the next guy comes up and says, ‘Are you kiddin’ me? That’s not Lucy Ball! That’s fuckin’ Lawrence Welk!’ It’s very difficult to say.” Above all else, Clifton Hill boosters like Parker resist the idea that the tourist strip is “tacky,” a word he deploys repeatedly in conversation. Tacky.

Late last September, news came of a Clifton Hill institution’s imminent demise. Rock Legends Wax Museum—which is technically on Centre Street, which is what Clifton Hill is called when it cuts northwest of the bisection of Victoria Avenue—was closing. Rock Legends (established, according to its bright blue-and-yellow signage, in 1983) warehoused sculptures bearing passing resemblances to a number of rock and roll superstars: the Beatles, Bono, Kiss, Bruce Springsteen, Chuck Berry, Alice Cooper.

The life-size figures were modelled in an inelegant, deeply uncanny, just-as-deeply-cheapo way that might frighten a young a child or amuse an adult ironist. Each one was made, by hand, by Pasquale Ramunno, by turns described as an accordionist and opera enthusiast who landed in Niagara in 1956, emigrating from Pacentro, Italy, a tiny village which is, incidentally, also the birthplace of Gaetano Ciccone and Michelina Di Iulio, who are Madonna’s paternal grandparents.

The word came courtesy of 91.7 Giant FM, “Niagara’s Classic Rock,” a station whose modest headquarters straddles the border between Welland and Port Colborne, where I was born and reared, and which, when I was a kid, was the first commercial radio station in Canada owned by an Indigenous woman. It is now being acquired by Stingray Group, a media multinational with employees on at least four continents. Like Clifton Hill, 91.7 has been steamrolled—or “revived”—by bland corporate aesthetics. Such, it increasingly seems, is the fate of much modern culture absorbed by the bloat of monopolistic interests.

“The city, and especially its tourist-baiting main drag, has long occupied his imagination.”

Tackiness gets a bad rap because it makes us feel like suckers. It offends our belief that we deserve better. We are allowed to marvel at top-shelf wax statues of celebrities or modern movie blockbusters because they meet some implicit standard of verisimilitude, because they look “real”: it’s okay to be crassly entertained so long as that entertainment passes some bar of acceptability. Anything that fails that standard is generally held to be tawdry or kitschy or cheesy—to be, in other words, beneath our esteem.

But tackiness of the kind you’ll find—or used to find—on Clifton Hill proves memorable, even affecting, not just because of some knowing irony. It’s because, I think, it feels so lovingly and painstakingly handmade. Who cares that Pasquale Ramunno can’t nail the details of Bruce Springsteen’s half-agape mouth? What lingers is not the perfect resemblance to the Boss but the sculptor’s efforts. Something similar can be said of the dumpy mannequins of Movieland and even the enormous Whopper-gobbling Frankenstein’s monster. Their profound flaws are an index of the sloppiness of humanity. They are perfectly imperfect. And this is certainly preferable to the alternative.

Recounting a June 1831 visit to Niagara Falls, the British novelist Fanny Trollope wrote: “We passed four delightful days of excitement and fatigue . . . we strove to fill as many niches of memory with Niagara as possible.” Modern Niagara Falls seems similarly keen on defining those niches of memory, but now, they aren’t being filled with reminiscences of its abounding natural beauty or even of the weird and cheap and seedy and bad. They’re being plastered over. Clifton Hill is rapidly gentrifying outside of its own tackiness. It’s especially despairing because, while there are many stateside locales where busloads of visiting looky-loos can pay good money to feel like suckers—Vegas, Reno, Times Square, Nashville’s Honky Tonk row, that sad strip in Hollywood where men dressed in superhero spandex pose with tourists for tips in Canada, Clifton Hill is basically nonpareil. And this may be a font of its specialness: in its ostentation and brazen indecorousness, it just seems straight-up un-Canadian.

The future projected by Shin and local business-improvement interests—of families ferried from one chain-dining franchise to another, with a pit stop, in recycling-bin-blue plastic smocks, under the Falls themselves—is utterly despairing. I want to see drunk and sweaty men sock each other in their soft pink faces. I want to see scammers and sketch-bags investing the strip with the vague threat of criminality we call “seediness.” Now, even an enormous ghoul munching a Burger King–branded Whopper sandwich feels like a local treasure, imbued with the residue of time, pressed into the supple wax of memory. It is, if literally nothing else, just extremely stupid. And that is so obviously more desirable than being nothing at all.