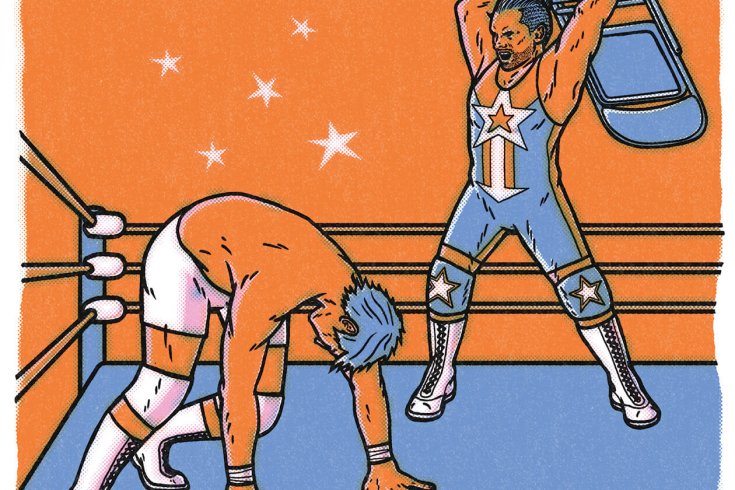

Troy Merrick races up behind his former teacher, “Wildman” Gary Williams, and pummels him in the back of the head. The older man falls to his knees, and Merrick lays a boot into his back, knocking him to the floor.

Most teachers wouldn’t appreciate being punched in the head, but these guys are professional wrestlers. It’s Friday night in Truro, Nova Scotia, and the two men are in the ring with fellow competitors Chris Cooke and Brody Steele as part of a tag-team match being held in a community-college gym. Two hundred and fifty fans, many of them children, have turned out to cheer and boo the local wrestlers they love—and love to hate.

Merrick stepped into the ring as a professional for the first time ten years ago, in Lamèque, New Brunswick, population 1,400. Back then, he was known as Sexton Phoenix, but in 2014, he rebranded himself. These days, he’s the American Patriot, and he usually enters the ring brandishing the Stars and Stripes, flexing his muscles in front of the flag while wearing a red, white, and blue singlet with stars on the chest and kneepads. He even has an American flag shield tattooed on his wrist. “Nobody wants to see a loudmouth American come out and tell you how much better his country is than yours,” Merrick says. “I’m a jackass. Everybody hates the Patriot—and it’s awesome.”

Old photos of Merrick show a chubby teen with bangs that hang low on his forehead. He says he was bullied as a child. “Growing up in a household with three women, wrestling provided me with positive male role models.” At five foot eleven and 185 pounds, Merrick is not a big man, but he lives by the credo of his childhood wrestling idol, Shawn Michaels: You don’t have to be big to be good. You have to be good to be good.

Today in Truro, boos rain down on Merrick. “Captain America!” a boy yells derisively from ringside. Another waves a “You Suck” sign every time the Patriot looks his way. When Merrick hears an insult, he turns and glares theatrically at the offender, pointing at them and shaking his head, clearly embracing the spectacle. Professional wrestling, after all, is equal parts showmanship and athleticism. The results of the matches are predetermined—performers know from the start who is going to win—but it’s always been that way. The big difference over the last few years is that the wrestlers and promoters have stopped pretending otherwise. “Starting out, showmanship was kind of my strength, and I developed the athletic ability as I went on,” Merrick says. “It’s really rewarding to be able to manipulate somebody’s emotions—to me, that’s the main point of wrestling.”

Merrick used to work as a broadcast journalist. But last year, he left his job at a radio station in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, to try to make it as a wrestler full-time. There’s a lot of travel and not much pay: this spring, he earned just over $2,000 for a month-long tour of the United Kingdom during which he wrestled thirty times in twenty-seven days. But there’s an easy camaraderie among the performers, and the audience is committed. A few rows back from the ring, a man proudly wears a T-shirt with the words “Our wrestlers are just as good as the ones on TV” in a handwritten scrawl.

Professional wrestling has a long history in the Maritimes. Talk to anyone over forty who has followed the scene, and you’ll hear fond memories of Atlantic Grand Prix Wrestling—a circuit that started up in the 1960s—and of the antics of luminaries such as Killer Karl Krupp and the Cuban Assassin. “Grand Prix Wrestling was our roots,” says Williams, forty-four. But wrestling is a cyclical business: during the early 1990s and mid-2000s, local promotions shut down and audiences across the East Coast dwindled. Now, Williams says, the Maritime scene is experiencing a resurgence. “Independent companies are doing really well, the crowds are up, and the talent is getting a lot better.”

Strangely enough, the recent upswing in the fortunes of industry giant World Wrestling Entertainment—which drew more than 100,000 fans to Wrestlemania in Dallas this year and has its own cable network—seems only to have helped the local wrestling scene. Fans can watch wrestling on TV any time, but that hasn’t stopped them from heading out to matches in a daisy chain of small towns across the region: Amherst, Pictou, Stratford, Bathurst.

Harold Kennedy has been watching the local scene develop in the Maritimes for about fifteen years. He’s been a fan, a promoter, a videographer, and one of the guys who stack chairs after the show is over. In Truro, he’s refereeing. “I’ve been to independent shows in Maine and Pennsylvania and out to Los Angeles, and the Maritime fan base is the most passionate group I’ve ever seen,” he says. In part, he attributes the fandom to a lack of options: small-town Nova Scotia isn’t exactly a hotbed of entertainment, and many adult Maritimers grew up watching the Grand Prix matches. “In a lot of the little towns we go to, there’s nothing else. That’s why wrestling is starting to come around.”

Shelley Brown, thirty-two, is a library assistant and devoted wrestling fan from Sydney who travelled more than three hours to see the matches in Truro, carrying a bag full of T-shirts from various local wrestlers. (She changes during the show.) She’s here with her father—the pair has watched the sport together since Shelley was a toddler. “We see families cheering or booing as a team—and just spending that time together. That’s always been a staple of the Maritime wrestling scene,” Brown says. “In order to really appreciate wrestling for what it is, you need to see it live. The fans can make or break a show, the wrestlers can make or break a show—and when they work together, it’s magical.”

There isn’t much glamour in independent wrestling. Small towns, fast food—and, tonight, a locker room with poor shower pressure and blocked toilets. But that magic Brown talks about keeps wrestlers like Merrick climbing back into the ring night after night. “If you can really feel the crowd, if you can feel your opponent and know what’s coming and know how to work, that’s truly what brings out the power of wrestling,” he says.

A couple of hours earlier, Merrick and Williams sat at a nearby Tim Hortons eating grilled-chicken wraps and deliberating over the number of calories in a strawberry-shortcake doughnut. Now they’re punching, kicking, and stomping each other with panache, and, after a strong start, things aren’t going so well for the American Patriot/Steele tag team. The Patriot leaps onto local boy Cooke as a prelude to a new jump-and-twist move Merrick wants to debut. But his timing is off—he winds up underneath Cooke instead.

Watching Merrick fall on his knees and get thrown to the floor, I wonder how long he can keep this up. At twenty-eight, he’s broken his ankle and numerous fingers, suffered multiple concussions, and damaged the medial collateral ligaments in his knees. Years of on-and-off steroid use have left him concerned about his long-term health. Wrestling is as physically demanding as Cirque du Soleil, he says. “But no one catches you.”

Before long, Merrick is pinned under Williams, the ref counts to three, the bell rings, and the men separate. As they leave, Steele glares hard at Merrick—the partner who has let him down in the ring. The two men walk down the makeshift aisle toward the backstage area. Once behind the black curtain, they grin and shake hands.

As they return to the locker room in the basement, heavy metal, punctuated by the occasional air horn, plays in the gym. The black curtain pulls back again, and “Country Idol” Kris Hicks, dressed in a black cowboy hat and unbuttoned plaid shirt over tight shorts, steps into the ring. Then sixteen-year-old Maddison Miles—the only woman on the card, wearing a T-shirt that says “Because rings are for girls”—makes her entrance, running down the aisle and slapping fans’ hands. Within minutes, the next match is underway.