Some find it strange that a person known for her novels and poetry would take to writing comic books called Angel Catbird. But I myself don’t find it very strange.

I was born in 1939 and thus of a reading age when the war ended and colour comics made a booming comeback. Not only did I read masses of comics in magazine form, I encountered many of the same characters in the weekend newspapers. Some of the comics were funny: Little Lulu, Li’l Abner, Mickey Mouse, Blondie, and so forth. Some were serious: Steve Canyon, Rip Kirby, and the unfathomable Mary Worth. And some were superheroes: Batman, Wonder Woman, Superman, Green Lantern, and their ilk. Some even aimed at improving young minds: the Classic Comics series had an educational bent. And some were just weird.

In this last category, I’d place Mandrake the Magician, Little Orphan Annie—in which nobody had pupils in their eyes—and Dick Tracy: surrealist masterpieces, all of them, though somewhat disturbing for children. A criminal who could assume anyone’s face, behind which he looked like melting Swiss cheese? It was alarmingly close to Salvador Dalí, and kept me awake nights.

Not only did I read all of these comics, I drew comics of my own. The earliest ones featured two flying rabbit superheroes. My older brother had a much larger stable of characters. They had more gravitas: they went in for large-scale warfare, whereas my own superheroes fooled around with the odd bullet. Along with the superhero rabbits, I drew winged flying cats, many with balloons attached to them. I was obsessed with balloons, as no balloons were available during the war. So I’d seen pictures of them, but never the actual thing. It was similar with the cats:

I wasn’t allowed to have one, because we were up in the Canadian forests a lot. How would the cat travel? Once there, wouldn’t it run away and be eaten by mink? Very likely. So, for the first part of my life, my cats were flying dream cats.

Time passed, and both the balloons and the cats materialized in my real life. The balloons were a disappointment, liable as they were to burst and deflate; the cats were not. For over fifty years, I was a dedicated cat person. My cats were a pleasure, a comfort, and an aid to composition. The only reason I don’t have one now is that I’m afraid of tripping on it. That, and of leaving it an orphan, so to speak.

As the 1940s changed into the 1950s and I became a teenager, the comic that preoccupied me the most was Walt Kelly’s Pogo, which, with its cast of swamp critters combined with its satire of the McCarthy era’s excesses, set a new benchmark: how to be entertainingly serious while also being seriously entertaining. Meanwhile, I was continuing to draw and to design the odd visual object—posters, for the silk-screen poster business I was running on the Ping-Pong table in the late fifties, and book covers, for my own first books, because that was cheaper than paying a pro.

In the seventies, I drew a sort-of political strip called Kanadian Kultchur Komix. I then took to drawing a yearly strip called Book Tour Comix, which I would send to my publishers at Christmas to make them feel guilty. (That didn’t succeed.) It’s no coincidence that the narrator of my 1972 novel, Surfacing, is an illustrator and that the narrator of my 1988 novel, Cat’s Eye, is a figurative painter. We all have unlived lives. (Note that none of these narrators has ever been a ballet dancer. I did try ballet, briefly, but it made me dizzy.)

And I continued to read comics, watching the emergence of a new generation of psychologically complex characters (Spider-Man, who begat Wolverine, et cetera). Then came the emergence of graphic novels, with such now-classics as Maus and Persepolis: great-grandchildren of Pogo, whether they knew it or not. Meanwhile, I had become more and more immersed in the world of bird conservation. I now had a burden of guilt from my many years of cat companionship, for my cats had gone in and out of the house, busying themselves with their cat affairs, which included the killing of small animals and birds. These would turn up as gifts, placed thoughtfully either on my pillow instead of a chocolate, or on the front doormat. Sometimes it would not even be a whole animal. One of my cats donated only the gizzards.

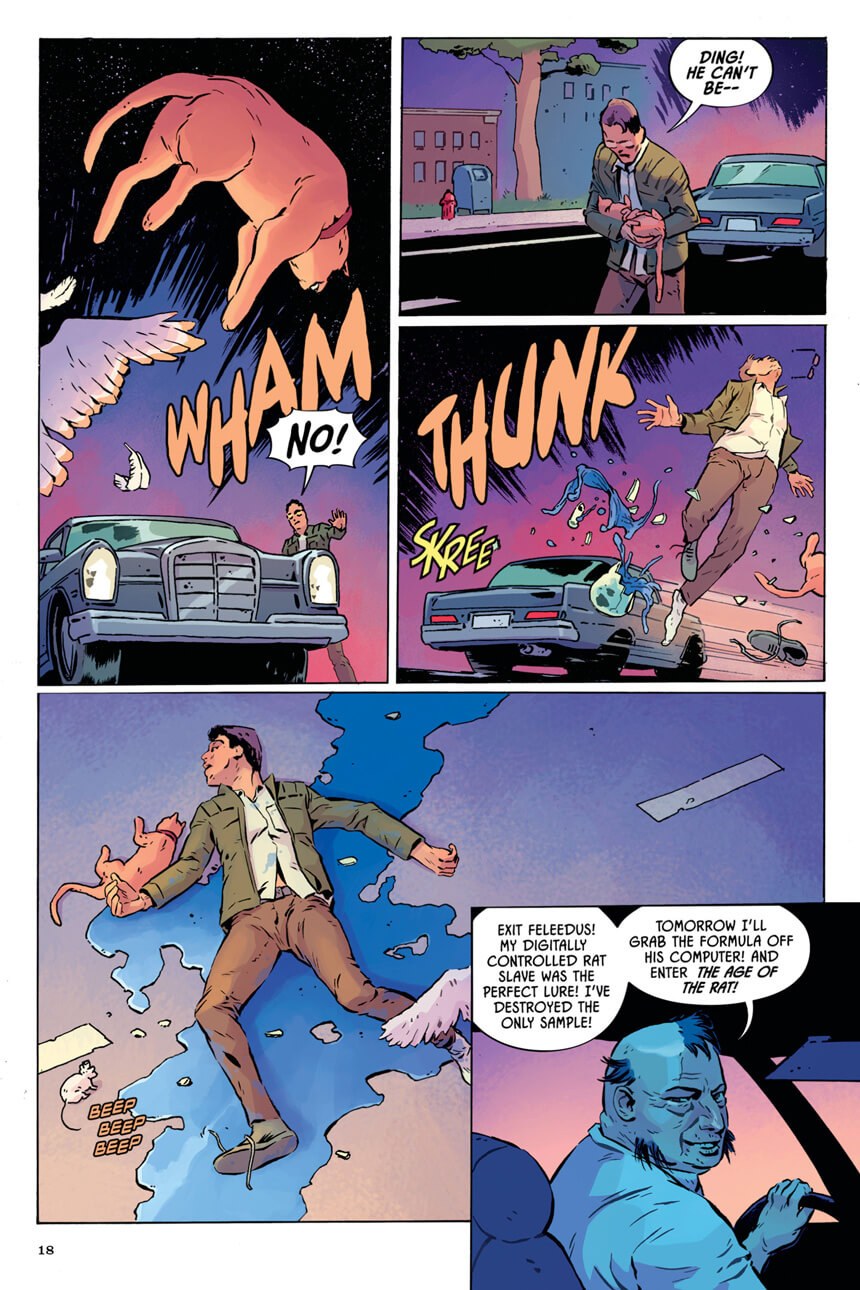

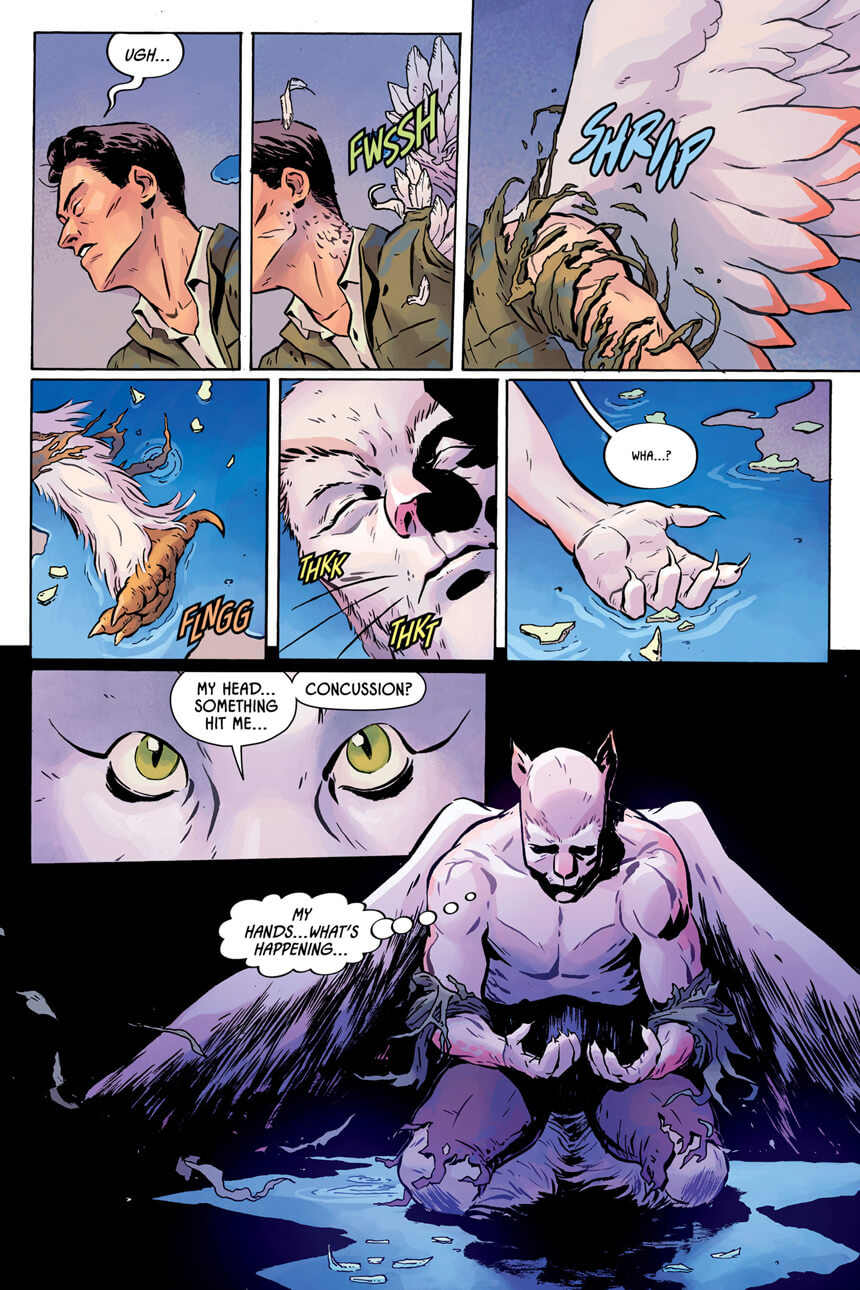

From this collision between my comic-reading-and-writing self and the bird blood on my hands, Angel Catbird was born. I pondered him for several years, and even did some preliminary sketches. He would be a combination of cat, owl, and human being, and he would thus have an identity conflict—do I save this baby robin, or do I eat it? But he would understand both sides of the question. He would be a flying carnivore’s dilemma.

But Angel Catbird would have to look better than the flying cats I’d drawn in my childhood—two-dimensional and wooden—and better also than my own later cartoons, which were fairly basic and lumpy. I wanted Angel Catbird to look sexy, like the superhero and noir comics I’d read in the forties. So I needed a co-author. But how to find one? This wasn’t a world of which I had much knowledge. Then up on my Twitter feed popped a possible answer. A person called Hope Nicholson was resurrecting one of the forgotten Canadian superhero comics of the wartime 1940s and fundraising it via Kickstarter. Not only that, Hope lived in Toronto.

I put the case for Angel Catbird to her, and, lo and behold, she came onboard and connected me with artist Johnnie Christmas, who could draw just the right kinds of muscles and also owl claws, and with publisher Dark Horse Comics. Watching Angel Catbird come to life has been hugely engaging. There was, for instance, a long email debate about Angel’s pants. He had to have pants of some kind. Feather pants, or what? And if feathers, what kind of feathers? And should these pants be underneath his human pants and just sort of emerge? How should they manifest themselves? Questions would be asked, and we needed to have answers.

And what about Cate Leone, the love interest? What would a girl who is also a cat wear while singing in a nightclub act? Boots with fur trim and claws on the toes? Blood-drop earrings? Such questions occupy my waking hours. What sort of furniture should Count Catula—part bat, part cat, part vampire—have in his castle? Should some of it be upside down, considering the habits of bats? How to make a white Egyptian vulture look seductive? (You know what they eat, right?) Should Octopuss have a cat face and tentacle hair? Should Cate Leone have a rival for Angel Catbird’s attentions—a part girl, part owl called AtheenOwl? I’m thinking yes. In her human form, does she work at Hooters, or is that a pun too far? So. Like that.

The science-and-conservation side to this project is supplied by Nature Canada, which is not only contributing the statistics found in the banners at the bottoms of the pages, but also running a #SafeCatSafeBird outreach campaign to urge cat owners not to let their cats range freely. The mortality figures for free-range cats are shockingly high: they get bitten in fights, hit by cars, eaten by foxes, and that’s just the beginning. So it’s good for cats and good for birds to keep domestic cats safe and in conditions in which they can’t contribute to the billions of annual bird deaths attributed to cats.

On catsandbirds.ca, cat owners can take the pledge; mounting pledge numbers could also mean better conditions for stressed forests, since it is migratory songbirds that weed insect pests out of trees. Cats aren’t the only factor in the decline of birds, of course—habitat loss, pesticides, and glass windows all play a part—but they’re a big factor.

There used to be an elephant who came around to grade schools. He was called Elmer the Safety Elephant, and he gave advice on crossing streets safely. If your school had managed a year without a street accident, Elmer gave you a flag. In my wildest dreams, Angel Catbird and Cate Leone, and maybe even Count Catula, would go around and give something—a flag, a trophy?—to schools that had gathered a certain number of safe-cat pledges.

If it does happen, I’ll be the first to climb into my boots with claws on the toes, or maybe sprout some wings, in aid of the cause.

Excerpted from Angel Catbird. Courtesy of Dark Horse Books.

This appeared in the September 2016 issue.