A pale yellow “Notice to Appear – To Write a Citizenship Test” arrived on Friday the 13th, five months after I mailed my application to the national processing centre in Sydney, Nova Scotia. It came without warning or ceremony, and much sooner than Citizenship and Immigration Canada’s website suggested it would. I had twelve days to prepare for the exam, which an increasing number of would-be citizens have failed since it was redesigned in 2012.

On paper, I didn’t need to spend much time studying. Since moving to Canada a decade ago, I have visited every province and one of the three territories; I have travelled the country by road, by air, by rail, by sea. I work for a magazine about Canada and its place in the world. Besides, CIC assures applicants that a single document—the glossy sixty-four page “Discover Canada: The Rights and Responsibilities of Citizenship”—contains all of the information a newcomer needs to pass the twenty-question test.

As a native Nebraskan, and a product of the US education system, I know the ABCs of standardized testing: the ITBS, the ACT, the SAT, the GRE, the GRE II. I’ve always done well on bubble tests (the GRE II being the glaring exception), and I’ve never been nervous about taking one. Until yesterday.

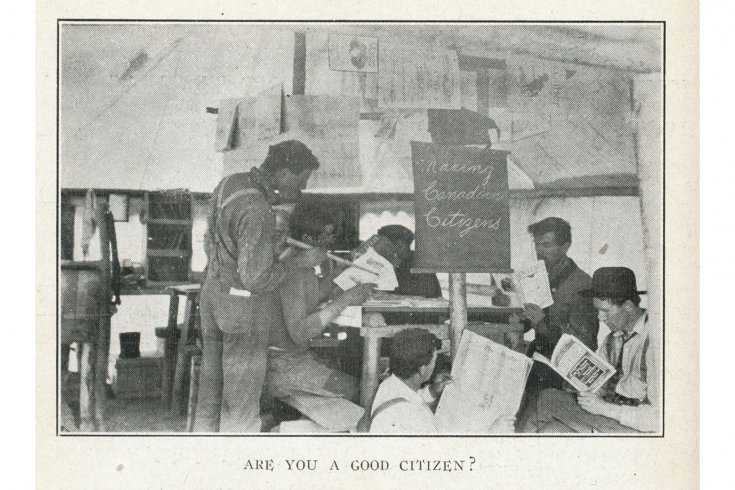

I was more than nervous when I arrived on the third floor of the Service Canada building in Scarborough, Ontario, twelve minutes before the 10:15 a.m. start. I was worried. Scores of people were already lined up, and they looked anxious too. Individuals and families, toddlers and seniors—we were all here to take the last step before swearing an oath to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, Queen of Canada, Her Heirs and Successors. People flipped through their dog-eared copies of “Discover Canada.” Siblings quietly quizzed each other on the number of federal ridings. The highest honour a Canadian can receive (it’s not the Order of Canada). The percentage of Canadians who work in the service industry. The two Canadians who invented the light bulb. The longest river in the country.

Those of us writing the exam (children and permanent residents over fifty-five don’t have to) were led into a classroom of sorts, with rows of chair-desks and no. 2 pencils. Our proctors—three women with more patience than those overly strident folks I remember from the SAT—stepped us through the bubble forms. Fill out your surname, one letter per box. Fully darken the circle below that corresponds to each letter. Do the same for your application ID. Easy. Except that many in the room had never seen a Scantron test; many had surnames longer than the forms allowed; many needed to hear the instructions multiple times, in less idiomatic English.

Earlier this week, former citizenship director-general Andrew Griffith raised concerns that fewer and fewer permanent residents were writing the test and taking the oath. CIC countered that Canada has among the highest naturalization rates in the world. News reports and CBC Radio spots only fuelled my anxiety. Failing—missing more than five of the multiple-choice and true-false questions—would be embarrassing, particularly back at the Walrus office. It would also mean sitting for the exam again in six to eight weeks. Another day off, many more passes through the guide, another trip to Scarborough. But I think my nerves had little to do with potential embarrassment or inconvenience.

Deciding to become a Canadian is not about the Rebellion of 1837–38, or the first leader of responsible government. It’s not about knowing that Sir Wilfrid Laurier Day is in November, or that oil was discovered in Alberta in 1947. Failure would represent more than my inability to master distilled (politically charged) talking points. It would represent doubt. What if I don’t actually understand my growing attachment to Canada, its history and its present? What if people are right when they say that I’m not really Canadian?

All in all, we spent more time filling out our names than I did writing the exam itself. I finished, met with a CIC official who verified my American passport and landing document, and who asked me about all the countries I have visited since 2008. She approved me for Canadian citizenship, told me to watch the mail about taking the oath, and sent me on my way. I left the building before most of the others had finished their tests, but I felt a kinship. I look different than them, and they almost certainly speak more languages than I do. Yet we all want to be here, and we all want to vote in the next federal election. Most of us probably went to Tim Hortons in the mall next door afterwards, and maybe more than a couple of us tweeted pictures of our celebratory maple-glazed doughnuts.

Citizenship isn’t about twenty arcane questions. The true test is whether you’re ready and willing to share a profound, albeit fleeting, experience with total strangers. An experience no natural-born Canadian will ever be fortunate enough to have.