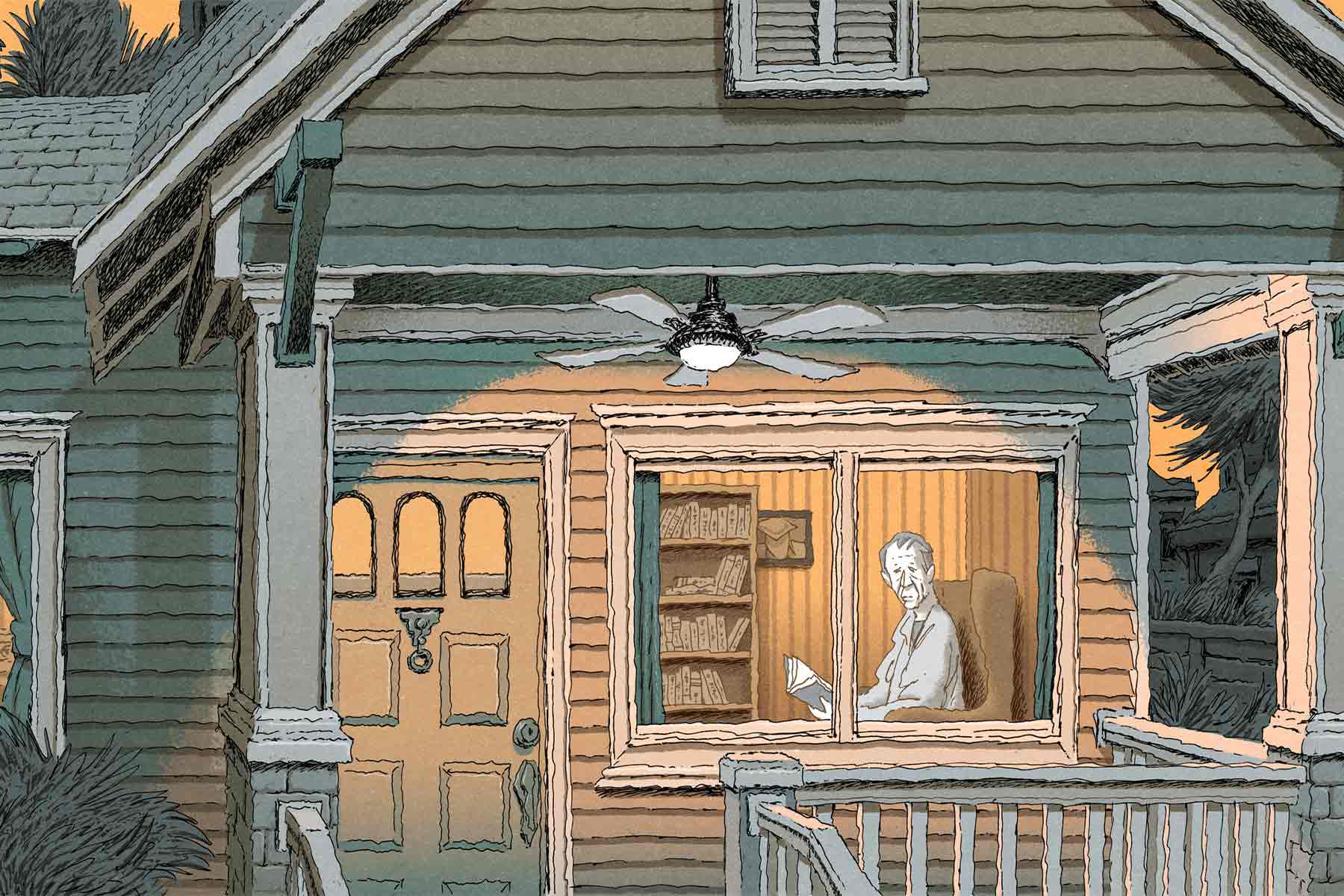

Bob Comet is, at first glance, a lonely man. A retired librarian in Portland, Oregon, he has no friends or family to speak of. Instead, he engages with the world mainly by reading about it. This changes one day when he comes across a woman in a pink sweatsuit staring blankly into a 7-Eleven fridge. He identifies her as a denizen of the Gambell-Reed Senior Center, and in an effort to find meaning in his golden years, he decides to volunteer at the old folks’ home. His way of giving back is by reading to them.

Hanging around Gambell-Reed’s eccentric inhabitants, Bob begins to reflect on his own quiet existence. The Librarianist, the fifth novel from Patrick deWitt, flashes back and forth in time to piece together Bob’s supposedly unremarkable life. In doing so, deWitt cobbles together a complicated but heartfelt treatise on introversion and the value of a life lived through books.

DeWitt has made a career out of bombastic protagonists—a pair of hitmen travelling across the Old West in The Sisters Brothers, a disgraced New York socialite and her son in French Exit. Bob, on the other hand, stands out precisely for his lack of noteworthiness. But his reclusiveness borders on the surreal. “He had no friends, per se,” deWitt writes on the book’s second page. “His phone did not ring, and he had no family, and if there was a knock on the door it was a solicitor; but this absence didn’t bother him, and he felt no craving for company.” Instead of its grand voyage or great romance, the central tension in The Librarianist arises from the ease with which Bob can retreat into made-up worlds as opposed to his lingering desire to connect with other people.

Surrounded by a community rapidly approaching death, Bob’s reflections take on an urgency: what makes a book worth reading is not far different from what makes a life worth living. Coming from a novelist now firmly in midcareer, and middle age, the questions posed in The Librarianist feel personal, as if deWitt is asking if his own imagined worlds have any value at all.

AVancouver island transplant living in Portland, deWitt seems to have certain parallels with Bob. For starters, he is something of an autodidact. In the early ’90s, deWitt dropped out of high school and began to pursue writing, during which time he searched for inspiration at his local library. The backstory to his 2009 debut, Ablutions, which loosely documents an alcoholic bartender’s notes for a book, feels pulled from fiction: it was published after deWitt, then a barman himself, plied a patron with enough booze to convince him to read his manuscript. The customer was D. V. DeVincentis, the High Fidelity screenwriter, who loved the book so much he found deWitt an agent. DeWitt quickly went on to mainstream success with his follow-up, 2011’s The Sisters Brothers, which won a slew of awards and was later developed into a film starring John C. Reilly and Joaquin Phoenix.

Also much like Bob, deWitt revels in literary tradition. DeWitt, who says he “doesn’t feel a part of any contemporary school,” reveres the craftsmanship of postwar Britons like Ivy Compton-Burnett and Barbara Pym, whose novels, like deWitt’s, possess the careful construction of origami. DeWitt is also known for his genre pastiches: The Sisters Brothers is a picaresque; Undermajordomo Minor, about a servant in a grand European castle, a gothic fable; and French Exit a comedy of manners. But if his previous novels were born out of the author’s enthrallment with the wide world of literature, in The Librarianist, deWitt seems to reflect on whether that fascination is worthwhile.

Bob insists early in the novel that he does not crave company, but he does not always appear to be a reliable narrator of his own emotions. He instantly admires the camaraderie among the lively members of Gambell-Reed, and he seems eager to invite them into his own world. He arrives at the centre armed with Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Black Cat,” but the residents are too disturbed by the feline abuse to stay in their seats. Maria, a Gambell-Reed employee, encourages him not to quit, to instead return without his props. “Leave those books at home, Bob,” she says. Bob wonders what he should do instead, a question that has both practical and existential implications. He isn’t sure how to interact with a world that isn’t tightly bound between covers.

He begins reflecting on moments in which life has peeled him away from a book. He describes being so inspired by adventure novels that he ran away from home at age eleven. He meets June and Ida—a pair seemingly inspired by Jane Bowles’s 1943 novel Two Serious Ladies—whose banter so consumes them that they frequently forget about their young companion. DeWitt relishes the uncanny collision between his bumbling protagonist and characters so witty it’s almost beyond belief. “The shrug is a useful tool, and seductive in its way,” June tells Bob when he struggles to find words in her presence. “But it is only one arrow in the quiver and we mustn’t overuse it lest we give the false impression of vacancy of the mind.” The women possess a mastery of language that bewilders Bob. He follows them around until they begrudgingly recruit him to assist in a mystery production. “Both our families have disowned us, naturally. And it has been a long while since we were barred from polite society,” June says as the two come out as actresses. “Ida and I are thespians, Bob.”

It makes sense, then, that Bob’s sojourn with June and Ida is one he thinks back to often, a memory that provokes a “chemical flooding his brain, the feeling of falling in love.” If books provide Bob refuge from an unpredictable world—dialogue and plot serving as preferable alternatives to bad conversation and fumbled plans—then June and Ida allow him to imagine what life could be like if only he could translate the perfected language of novels to his own real life. This becomes the animating tension of his existence, one that he resolves by retreating further into the written world.

Later, at the end of high school and back at home living with his single mother, Bob decides to become a librarian despite an older librarian’s attempts to dissuade him. This mentor regretfully informs Bob that librarianism, which he defines as “the language-based life of the mind,” is a relic of the “syrup-slow era of our elders.” Just as there are no longer metalsmiths, the mentor warns, the entire literary apparatus will soon be obsolete. Bob pursues his calling undeterred.

He even begins to make progress in developing a social life: he meets Ethan, a handsome playboy who becomes his best friend and foil. “I keep meaning to get to books, but life distracts me,” Ethan says to Bob. “See for me, it’s just the opposite,” Bob replies. He also meets Connie, and for the first time, he falls in love. She returns his affections, and they marry. But like a romance novel gone awry, Connie and Ethan hit it off too. The two meet-cute on a bus when Ethan recognizes Connie by her library copy of Crime and Punishment—the same one that Bob once lent him. Bob’s attempts at bridging life and literature fail, the joys of a book recommendation tragically misfired.

He can sense his wife and best friend growing closer but can never bring himself to say anything. When Connie does eventually run off with Ethan, all Bob can think to do is smoke three packs of cigarettes. When she sends him a final letter, for once, Bob refuses to read.

In fact, words seem to stop finding their proper meaning. In one scene, Bob claims never to have experienced schadenfreude; then, a few pages later, he recalls the manic joy he experienced when, less than a year after his and Connie’s divorce, Ethan is struck dead by a car. Bob claims to be content only ever having loved once, that he likes living alone, but he peers into his neighbours’ windows, searching for signs of life. His enclosure in the world of books not only inhibits his understanding of others but also his knowledge of himself.

When the story returns to the present of early aughts Portland, Bob falls down the steps of his home and breaks his hip: living alone is no longer feasible. Maria asks him to return to Gambell-Reed, this time as a resident. This atypical family is a deserved ending for Bob, but deWitt teeters toward the saccharine as Bob starts dreaming of his former library stead. “He understood how lucky he had been to have inhabited his position,” deWitt writes. “He had seen the people of the neighbourhood coming and going, growing up, growing old and dying. He had known some of them too, hadn’t he?”

And it’s here that deWitt’s attempt to answer whether Bob’s fascination with literature—and, by extension, his own—is conducive to a meaningful life proves a bit lacking. For most of the novel, deWitt is more preoccupied with having fun with words and language than providing a serious response. When he does finally get around to exploring the question, it marks a tonal shift, one that feels like a tossed-off balm for a moribund Bob. Bob’s insistence that he had in fact serviced his community and “been a part of it” registers as rushed. (It calls to mind a similarly dissatisfying late-stage detour in French Exit, when Frances Price, a woman so committed to nihilism that she sets a bouquet of flowers on fire because a waiter does not bring the cheque fast enough, becomes “sort of a joiner” as she approaches the end of her life.)

The Librarianist is most compelling when deWitt commits to Bob’s disappointments and to the notion that reading about fictional worlds can provide meaning—but only to a point. In this ill-fitted happy ending, deWitt returns to his trusted shrug; sure, he seems to say, a life lived through books can probably be worthwhile. For a writer perhaps imagining how he might feel about this devotion in thirty-odd years, it seems like he may be trying to convince himself more than his readers.

If The Librarianist is somewhat lacking in this regard, deWitt at least never strays far from what makes his novels so delightful: his dexterity with language, his interest in what happens when words fail, and the rare moments where they land. He ends on a note that is fittingly trivial. Bob must bob for apples at a Gambell-Reed Halloween event. “Bob! Bob! Bob!” the crowd impels him. Here, the incongruities of language, the ability to twist words at a moment’s notice, are not resolved by reading Tolstoy to the seniors. The pun is undeniably stupid, and Bob cannot help but laugh.