There was a time when John Irving’s madcap, endearing, and at times implausible fiction ruled the American imagination. From his 1978 coming-of-age classic, The World According to Garp, to his 2000 Oscar for best adapted screenplay for The Cider House Rules, he outshone practically every other literary novelist.

In those two decades, Irving was everywhere, thanks to his signature vision of genteel alienation among the upper middle classes. But his command of the country’s arts and letters has loosened considerably ever since two airplanes flew into the World Trade Center. When the nation’s priorities changed profoundly and unexpectedly in the George W. Bush years, Irving’s idea of Americans began to feel almost quaint. His writing has never really recovered, and most readers would be hard pressed to name anything he’s published in the twenty-one years since.

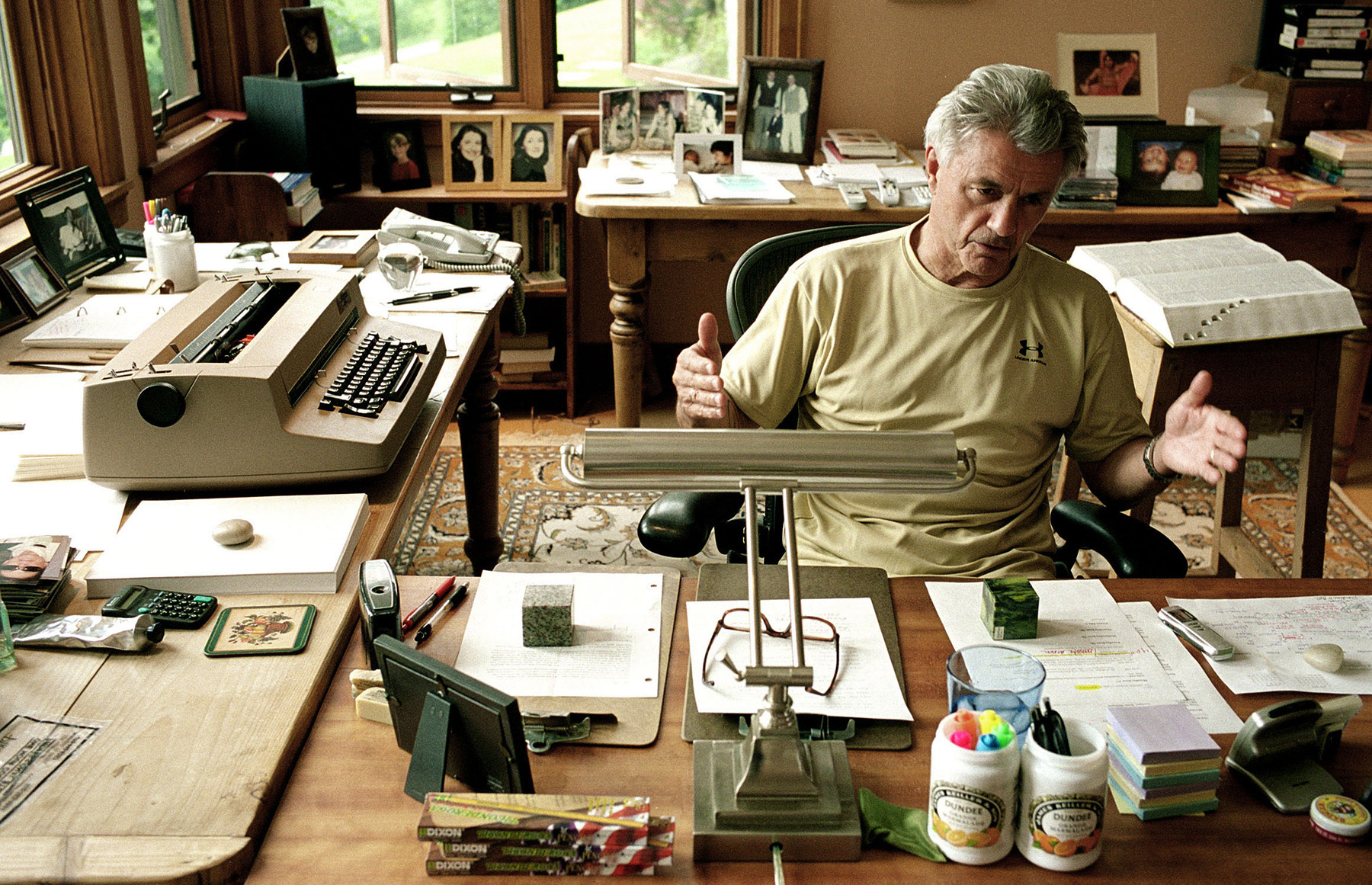

Now eighty, Irving appears to be nostalgic for those early days. At the centre of his fifteenth novel, the brick-heavy 912-pager titled The Last Chairlift, is Adam Brewster, a man a lot like Irving himself: a successful novelist and screenwriter looking back, at the end of a long life.

Born in 1941 (a year before Irving) to a single mother, Adam grows up in Exeter, New Hampshire (Irving’s hometown). Like Irving, who once suffered a hernia after challenging his daughter, Eva, to a quarter-mile foot race, Adam’s family is competitive—in their case, the extended clan shares an obsession with skiing, which leads to many detailed pages about a sport whose finesse and strategy, along with the characteristics of various slopes from Aspen to Maine, the author has harnessed to give the novel an extravagant sense of texture and place.

Irving follows Adam as he rebels against the family culture and refuses to excel at the sport. As a boy in the 1950s, Adam is prone to blaming his mother, Rachel—called Little Ray by the family—for abandoning him for six months each year in the course of her work as a ski instructor, during which she leads a hidden life with people he never meets. Among them is Adam’s father, whose identity Little Ray refuses to reveal. The only detail Adam has is that he was conceived in Aspen. Adam is, in many respects, reminiscent of the protagonist of The World According to Garp. Like T. S. Garp before him—who is named after the severely brain-damaged soldier whom Garp’s mother, Jenny Fields, uses to get pregnant—Adam feels he cannot know himself without a centralizing male figure in his life.

As a child, Adam suspects his mother loves skiing more than him, and his aunts regularly deploy the sport to criticize their younger sister’s lifestyle choices and athletic limitations. For those long months when Little Ray is off carving down mountains, Adam is raised by his wise grandmother, who reads him Moby Dick, and his nonverbal grandfather, known as “diaper man,” who once had ambitions to be the principal at the local prep school but now can no longer take care of himself. His inability to speak is attributed to the shock he endured after learning of Little Ray’s decision to have Adam without a husband.

The Last Chairlift is structured to allow Adam to metaphorically ride up and down the slopes of his life from his seat in the present day, looking back on the people and events that shaped him. Sometimes his stories follow the linearity of his memories; at other times, they are presented as drafts of unpublished screenplays.

Adam’s vulnerability never fully fades as he grows up, and Irving steadily reveals Little Ray’s true nature as a lesbian trying to navigate a world that won’t accept her. Covering the 1940s and ’50s, an era when American intolerance still held a stranglehold on society, The Last Chairlift is in large part a novel about how people of sexual difference cover up their secrets to conduct their daily lives.

Irving has built a storied career writing about those marginalized for their sexual orientation and has long described these lives with complexity. While he was once praised for addressing LGBTQ+ issues in the 1980s and 1990s—especially unlikely for an author whose books were in every airport and on every bedside table—he’s now writing in a world where such subjects are neither surprising nor radical. And, increasingly, they are within the purview of the communities who identify with them. The Last Chairlift has many similarities with Irving’s classic novels, but times change, as do contexts. It raises the question whether audiences will still come to Irving to hear these stories or to see themselves reflected in his work.

Readers familiar with Irving’s career will know what to expect from The Last Chairlift. Wrestling, sexual confusion, New Hampshire, prep schools, strong mothers, absent fathers, muted characters, improbable plot twists—all these tropes make encore appearances. They form a kind of winking mythology for Irving’s long-time admirers and act as ammunition for his detractors, who feel he too often retreads the same ground. In 2005, Kirkus Reviews castigated Until I Find You, a novel of similar length, structure, and autobiographical bent, for putting readers through “nearly 700 pages of repetitive, self-indulgent twaddle.”

Some people will inevitably think the same of The Last Chairlift, though Irving has remained unapologetically steadfast in his craft across six-odd decades.

He has declared himself a proudly old-fashioned kind of writer who offers paternal, godlike omniscience over every aspect of a story. “Those novels of the nineteenth century were the models of the form for me,” he once said, nodding to Charles Dickens and Herman Melville. “I wanted to be a novelist like that. . . . There’s no danger in imitating a writer from another century, the language has changed. . . . If your literary heroes are too close to your own generation and your own time, there is the danger that you will sound like an imitator.”

The Last Chairlift, however, arrives after a paradigm shift in how demographics communicate and how our culture organizes itself around the idea of representation. Through the 2010s, critics began to dismantle the status of many twentieth-century icons—from Irving’s predecessors like J. D. Salinger to peers like Norman Mailer, down to those who followed in his footsteps, like David Foster Wallace and Junot Diaz. Many have seen their stock fall: some due to shifting concepts of how maleness should be depicted on the page and others due to abusive behaviours they displayed in their private lives. John Irving, however, has not faced these problems. Five years ago, the fortieth anniversary of Garp saw him take a victory lap, where he was lauded for the space he afforded strong women and queer characters long before any of his alpha-male peers did.

For a man prone to writing fat books, Irving has been consistently respectful of those who, in previous eras, had to hide away many aspects of their lives. A decade ago, while promoting In One Person, he began to open up about why he wrote a novel about a bisexual man who falls in love with an older transgender woman. Part of the decision, he said, had to do with his daughter Eva, who came out to him. Irving said he wanted to write books where those close to him felt seen. He also noted that he’d “always identified with and sympathized with a wide range of sexual desires. . . . It turned out that I liked girls, but the memory of my attractions to the ‘wrong’ people never left me. The impulse to bisexuality was very strong; my earliest sexual experiences—more important, my earliest sexual imaginings—taught me that sexual desire is mutable.”

Until The Last Chairlift, In One Person was Irving’s most prominent work that focused directly on sexual and gender orientation. The direction proved fruitful, reinvigorating an already storied career: In One Person won him two Lambda Literary Awards, including the Bridge Builder Award honouring allies of the LGBTQ+ community.

In The Last Chairlift, revelations of sexual identity are high-water marks in a story that is otherwise filled with overly long character descriptions. Little Ray’s friend Molly is just a ski buddy, known as “the night groomer,” until a fourteen-year-old Adam catches her and his mother in his own bed one night, “naked and locked in an upside-down embrace, their faces buried between each other’s legs, their hands holding fast to each other’s buttocks.”

After that fateful incident, Adam’s innocence about his mother is lost, and Molly forever becomes Little Ray’s partner and lover. “When you’re a child,” Adam narrates, “you think childhood is taking too long—you can’t wait to grow up. One day, the growing up has happened; you missed it, and you’re trying to seize it after the fact.”

Complicating Adam’s sense of self, this tryst is discovered the night of Little Ray’s wedding to an English teacher at Adam’s prep school, Elliot Barlow, a snowshoer he had introduced to his mother in the hopes that she would be attracted to Elliot’s small size—he is four-foot-nine. One of the few details Adam knows about his father is that he was a very small man. Almost as a substitute for gaining his mother’s validation, “I developed a preternatural interest in what passed for physical affection or intimacy between my mother and the snowshoer.”

Little Ray may have only been looking for a “beard,” a man who fronted as a husband for a lesbian, but that suited the English teacher just fine. It turned out Elliot was gay anyway and looking for his own convenient arrangement. “In those days—the end of the 1950s,” Adam notes, “I don’t believe I ever heard the word homophobe. There were clearly a lot of homophobes around, but the word wasn’t in use yet. If anyone had known it, it would have been Mr. Barlow, but not even he was saying it.”

By the early ’70s, Elliot would move to New York and follow through on his lifelong aspiration to live as a transgender woman, an echo of Roberta Muldoon, the former football player turned family confidante in The World According to Garp. But the New York of those days was not as ready for her openness. “The snowshoer hadn’t grown up as a girl,” Irving writes, “she wasn’t lucky to be finding out what dickheads most men were when she was an attractive woman in her forties.”

In these instances, when Irving is envisioning Adam’s chosen family, he is masterful at teasing out a character’s true self across hundreds of pages, and that’s when the imposing length of the novel aptly captures the time we spend with those close to us and how, little by little, we see them orbit toward their true selves.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals have often played parts in Irving’s carnivalesque plotlines. Frank, the eldest of the Berry children in 1981’s The Hotel New Hampshire, came out at age sixteen. There was Johnny Wheelwright, the “non-practicing homosexual” narrator of A Prayer for Owen Meany, and the trans serial killer and gay twins in A Son of the Circus. These were all minor roles compared to the space afforded to the cast of The Last Chairlift, which follows In One Person in expressly seeking to make LGBTQ+ experience the focus of its narrative.

Yet much has changed in the decade since Irving was commemorated with his Lambda awards, and even more has changed since The World According to Garp first compelled readers to “joke about and laugh at our tragedies,” as the New York Times noted in its initial impressions. An entire generation of previously marginalized writers—both in terms of their sexuality and social status—has not only emerged into the mainstream but has also been celebrated by it.

It’s one thing to commend Irving’s craftsmanship in his dignified illustrations of LGBTQ+ characters. It’s another to ask who we would rather hear about marginalization from: Irving or those who have struggled individually, socially, and systemically to become more visible?

The literary world is now blooming with voices once considered “outsiders.” As John Self wrote in his essay “The Rise and Fall of Sad White Men” earlier this year in The Critic, “In a world where fiction is as likely to be marketed on its author’s story as its characters’, we want to hear from other people. And maybe it’s not just readers, but literature itself, which has become exhausted by the same stories.”

The self-representation of such voices has found readers precisely because they are able to offer new linguistic and stylistic approaches to present their identities. Will a Dickensian novel like The Last Chairlift, still rooted in the dusking privileges of the “Great American Novelists,” appeal to those flocking to more authentic representations, or does it risk merely co-opting struggles in the name of advancing its author’s social outlook? Here in Canada—where Irving has lived in part for more than three decades—recent years have seen lauded works by Canada Reads winner Joshua Whitehead, Amazon First Novel Award winner Casey Plett, and the 2022 Prix des libraires winner Gabrielle Boulianne-Tremblay, to name a few.

Such questions inevitably emerge across The Last Chairlift ’s 900 pages. In the ’80s, T. S. Garp was refreshingly different when he emerged as the poster boy for an emasculated generation of man-children. There was an authenticity there that readers saw as rooted in the author’s own upbringing. That licence of lived struggle in hand, Irving and his readers had great fun with the caricature of a frustratingly precocious, overemotional Garp as he is coached sexually and philosophically by the towering presence of his mother. The uneasy zeitgeist of sexual and social politics that cemented Irving’s reputation can still be found all over pop culture—the recent Netflix series Sex Education, which follows an awkward high schooler and his sex therapist mother, appears to nod affectionately toward Garp’s Oedipal family dynamic.

By contrast, The Last Chairlift rarely feels fun in its attempts at being progressive. Irving still relies on the kind of slapstick that defined the leads of his more youthful novels, and Adam goes through familiar motions as he searches for meaning while being surrounded by a carousel of larger-than-life personalities. But the results, after four decades of weathering social changes, are decidedly more contemplative and long winded.

In an interview for his previous novel, 2015’s Avenue of Mysteries, which features another aging writer grappling with memories from his boyhood, Irving described recurring manifestations from his autobiography as a catalyst for taking risks in his fiction. “I’ve always written about what I fear. Maybe the most autobiographical element in my novels is that they’re not at all about what has happened to me, they’re much more about what I’m afraid of, much more about what I hope never happens to me or to anyone I love.”

Readers today may wonder if this inclination toward reuse hasn’t grown, well, a tad predictable. Where exactly is the risk in this fiction? The Last Chairlift is a wandering book held together by Irving’s steadfast insistence on microdetailing every scene to the point of suffocation. For long stretches, its only discernible plot is how Adam navigated Irving’s personal boyhood mythology to become a successful writer, which is about as navel gazing as it sounds. We are meant to spot the contrasts between life and art and make the most of those results, even as we feel we’ve already heard the answers. Instead of seizing this moment, both Adam and Irving appear to yearn for a time that was simpler in some ways and more complicated in others.