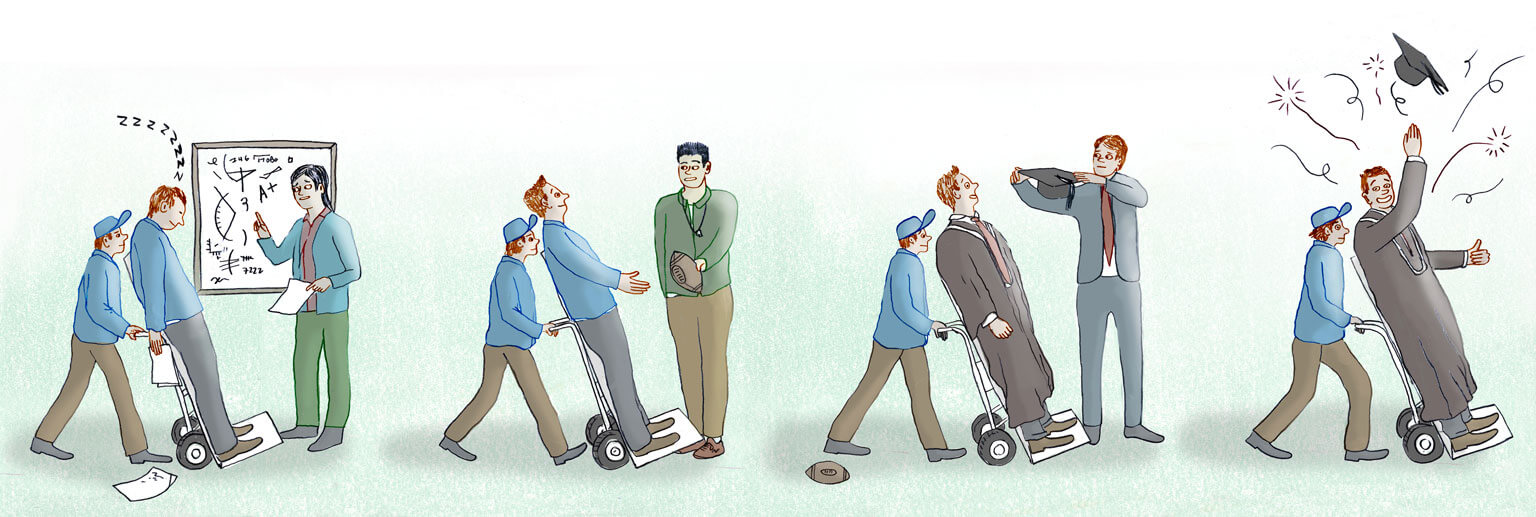

For the past seven years, I’ve polled my students at the University of Prince Edward Island on two questions. First: If you were told today that a university education was no longer a requirement for high-quality employment, would you quit? Second: If you decided to stay, would you then switch programs?

Positive responses to both questions run consistently in the 50 percent range. That means at least half of my humanities students—or about 750 since 2007—don’t want to be there.

Why not? A university degree, after all, is a credential crucial for economic success. At least, that’s what we’re told. But as with all such credentials—those sought for the ends they promise rather than the knowledge they represent—the trick is to get them cheaply, quickly, and with as little effort as possible. My students’ disaffection is the real face of this ambition.

I teach mostly bored youth who find themselves doing something they neither value nor desire—and, in some cases, are simply not equipped for—in order to achieve an outcome they are repeatedly warned is essential to their survival. What a dreadful trap. Rather than learning freely and excelling, they’ve become shrewd managers of their own careers and are forced to compromise what is best in themselves—their honesty or character—in order to “make it” in the world we’ve created for them.

The credentialing game can be played for only so long before the market gets wise and values begin to decline. I have been an educator in Canadian universities for over fourteen years, having taught some eighty-five liberal arts courses. During that time, evidence has mounted showing that a bachelor’s degree from a Canadian university brings with it less and less economic earning power. Last year, the Council of Ontario Universities released the results of the Ontario Graduates’ Survey for the class of 2012. It’s one of the few documents in Canada that tracks the employment rates and earnings of university graduates. Six months after graduation, the class of 2012 had an average income 7 percent below that of the class of 2005. Two years after graduation, incomes dropped to 14 percent below those of the 2005 class.

Though there are likely several reasons for this decline (increases in the number of graduates, demographic shifts in markets, precarious labour), one in particular matches perfectly with the type of change I’ve observed on my watch: the eradication of content from the classroom.

What kind of students are produced by such contentless environments? A couple of years ago, I dimmed the lights in order to show a clip of an interview. I was trying to make a point about the limits of human aspiration, a theme discussed in one of our readings, and I’d found an interview with Woody Allen in which he urged that we recognize the ultimate futility of all endeavours (a tough sell in today’s happiness market). The moment the lights went down, dozens and dozens of bluish, iPhone-illumined faces emerged from the darkness. That’s when I understood that there were several entertainment options available to students in the modern university classroom, and that lectures rank well below Twitter, Tumblr, or Snapchat.

Yet you can’t get mad at students for being distracted and inattentive, not like in the old days. “Hey, you, pay attention! This is important.” Say that today, and you won’t be met with anger or shame. You’ll hear something like “Oh, sorry sir. My bad. I didn’t mean anything.” And they don’t. They don’t mean anything. They are not dissing you. They are not even thinking about you, so it’s not rebellion. It’s just that the ground has shifted and left the instructor hanging there in empty space, like Wile E. Coyote. Just a few more moments (or years), and down we’ll all fall. These people look like students. They have arms and legs and heads. They sit in a class like students; they have books and write papers and take exams. But they are not students, and you are not a professor. And there’s the rub.

All efforts to create the illusion of academic content are acceptable so long as they are entertaining, and successful participation requires no real effort and no real accountability. Serial use of YouTube clips, Prezi presentations, films, and “student-centred learning activities” continues to be peddled for pedagogical relevance. Last term, I was driven from my office on many occasions because the movie soundtracks emanating from the seminar room next door were so loud and unrelenting that I couldn’t concentrate.

If you’d like a sense of how content-free it can get, here’s a case in point: I have heard of an instructor, one sans PhD, who assigned his students videos of himself talking about this or that subject as their class text. A digital lecture is assigned as preparation for a live lecture that will be about a digital lecture. And this not from a Hannah Arendt or an Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, but from a partly educated sessional instructor with a curiously inflated sense of self.

If you find this troubling, consider the new “business model” proposed for universities in 2009 by Charles Manning, the chancellor of the board of regents in Tennessee. Manning thought he could save universities a good deal of money by offering students a tuition discount if they agreed to “work online with no direct support from a faculty member.” Digital lectures for live classes with real students? Sounds expensive. How about no lectures, no students, and, best of all, no professors—just student-directed online activity at cut-rate prices? If this sounds to you like a typical Wednesday night of surfing the web, that’s because it is. How universities could persuade anyone to pay for this kind of experience, discount or not, is a mystery to me.

Great works—of science, art, literature, philosophy, and history—are the giants on whose shoulders we stand in our efforts to become giants ourselves. The fact that such works may now plausibly be replaced by narcissistic and transparently self-promoting twaddle, or indeed by nothing at all, is a sign of the nihilism of the modern academy. This is the classroom in which our sons or daughters (or you) very likely sit each day, so let’s map the contours of its nihilism a little more systematically.

Students today read very little. In 2009, the Canadian Council on Learning reported that 20 percent of all university graduates in Canada fell below Level 3 (the minimum level of proficiency) on a prose literacy scale provided by the Programme for International Student Assessment. That proportion was expected to rise.

I see ample evidence of this at UPEI. In one course I co-taught with several other faculty members, the readings were posted online, which allowed us to map access patterns. In that course, readings were accessed—not necessarily read—by 5 to 15 percent of the enrolled students. The same pattern was confirmed by textbook sales in a course from the previous year. I was teaching George Orwell’s 1984, and I had ordered 230 copies based on enrolment numbers. At the end of term, the bookstore had sold only eighteen copies, a hit rate of about 8 percent.

It may be that some students already had the book or had purchased it from another source. But the quality of the essays and midterm exams suggested a different story, as did students’ own explanations of their actions.

If you had a light-bulb manufacturing company and your staff members were permitted to remain ignorant of filament oxidization, you would produce bad light bulbs, and you’d soon be out of business. If you teach ancient Greek history and allow your students to remain ignorant of Thucydides, Herodotus, and Xenophon, not only will they write terrible papers, but they won’t know anything about how the ancient Greeks lived and fought and loved, and what that might teach them about their own lives.

But don’t worry—you won’t go bust because of this failure, not in the modern university. So long as your class is popular and fun, you’ll be favoured by the administration and probably receive a teaching award. This, even though your students will leave your class in worse condition than they entered it because you will have pandered to their basest inclinations while leaving their real intellectual and moral needs unmet.

University administrators have discovered that only in exceptional circumstances is the “success” of a classroom positively correlated with the academic excellence of its instructor. In fact, it’s more likely that the two are inversely correlated. The greater the instructor’s academic excellence, the more work she requires of students, the less “fun” they have (of the type I’m describing, at least—for some of us, real effort is fun), the poorer her student evaluations, the lower her subscriptions, and, therefore, the less “successful” her classes.

So why care about academic excellence at all? Why care whether your faculty members know their subjects thoroughly or have real degrees from real institutions when the mere appearance of these things will do?

In place of full-time academic staff, the university is filling up with a new class of instructors who march to a different drum. I’m not speaking about occasional or term contract staff, many of whom are first-rate scholars and teachers.

The instructors I’m talking about are those with terminal master’s degrees, sometimes in bona fide academic disciplines but increasingly in professional programs that may have much more to do with technique, or scholarly writing about technique, than with scholarly work per se. A master’s of education degree, for instance, may be acceptable for teaching students in bachelors of education programs, though a PhD is certainly preferable. It is, however, completely inadequate when teaching those pursuing regular bachelor’s degrees because the minimum requirement for teaching undergraduates is a graduate degree in the relevant discipline being taught. Yet MEds are routinely allowed to teach undergrads at my university, even though there are countless unemployed PhDs looking for work. For a long time, such people received only the scraps from the academic table—the odd sessional contract required to fill a temporary and unanticipated hole in the timetable or, more often, an administrative post in student services or the office of a high-ranking administrator. But administrators have begun to understand the real value of such people.

First, they are not scholars but employees. They think of administrators as people they work for rather than people who work for them by supporting their teaching and research. Second, they are professionally vulnerable and therefore remain mostly silent about critical matters. If a sessional instructor complains publicly about her institution or its declining standards, she will do so only once. Like a worker at a Mexican resort, if she refuses to cooperate and insists on talking to the guests about the truth of the place, she will be summarily dismissed and replaced by one of the hundreds just like her, ready to assume her position.

Finally, the very act of employing such people denigrates real scholars and scholarship by definition. If a person who knows next to nothing of what you know can do what you do just as well as you, then what is the value of what you know?

There is no clearer example of administrators’ contempt for faculty. But there is also no clearer example of their contempt for students. Undereducated instructors are compromising the value of your sons’ and daughters’ educations. But these instructors also allow administrators, many without PhDs, to weaken and destroy real academic departments, thereby giving themselves a free hand in setting a curriculum that has far less to do with knowledge than with pandering to market forces and student whims.

That curriculum? Life skills, university transitions, critical thinking, leadership, and communications—all modern mouthwashes of the “applied” course industry, designed to give a pleasant taste of practicality to humanities programs otherwise deemed useless. This curriculum may “pay” in the short term—more bums in chairs, the appearance of “relevance,” the mandatory homage paid to the god of “innovation.” But, in the real world, its effects are disastrous. In their 2010 book on higher education, Academically Adrift, Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa look at 2,300 students enrolled at a range of four-year colleges and universities in the United States. They found that 5 percent of students failed to show any statistically significant improvement in critical thinking, complex reasoning, and written communication after the first two years of college, and 36 percent showed no progress after four years. This, in my opinion, is what happens when a curriculum is designed to be a mirror. When students look into it, they encounter no enigma, no “other” luring them from their solitude. All they see is a reflection of themselves.

Universities seek ways of obscuring the truth of their decline while also creating the impression of ever-increasing achievement. How is this grand trompe l’oeil sustained? Behold the growth of university public relations offices, or communications departments, as they are more often called these days. These offices and departments work directly for the upper administration, and so do its bidding without resistance. They advertise the university, inflating its accomplishments and spinning its failures so as to maximize exposure and limit damage. And they are often quite well resourced. At my university, which is a small, primarily undergraduate institution with a student population of roughly 4,400, this department has a full-time staff of twelve.

Another remedy is the “building program,” for which capital funds are solicited from various governmental and non-governmental sources to help “build the future” of the institution and its community, a future that usually assumes the face of one or another professional program—nursing, engineering, education. In some cases, of course, these building programs are warranted. However, they are often undertaken not to serve real needs but to generate revenue and pad the CVs of senior administrators in preparation for their next career appointments. Frequently, they draw operational monies from existing programs in order to sustain themselves. But what photo opportunities they make possible.

Yet another trick is simply to juke the stats. Over the past fourteen years of teaching, my students’ grade-point averages have steadily gone up while real student achievement has dropped. Papers I would have failed ten years ago, on the grounds that they were unintelligible and failed to meet the standard of university-level work, I now routinely assign grades of C or higher. Each time I do so, I rub another little corner of my conscience off and cheat your son or daughter of an honest low grade or of a failure that might have given rise to a real success.

I am speaking, of course, of grade inflation. For faculty, the reasons for it vary. It can help them avoid time-consuming student appeals, create a level playing field for their own students in comparison to others, or boost subscription rates. Since most degrees involve no real content, it doesn’t matter how the achievement is assessed. Beyond questions of mere style, there are no grounds for assigning one ostensibly well-considered paper an A and another a B when both marks are effectively illusory. Let the bottom rise to whatever height is necessary in your particular market, so long as there remains some type of performance arc that will maintain the appearance of merit.

But as practices change, so do habits of mind and expectations.

If this practice begins early enough, say in middle or secondary school, it will become so entrenched that, by the time they reach university, any violation of it will be taken as a grievous and unwarranted denigration of their abilities.

Perhaps, somewhere deep down, they know their degrees are worthless. But anyone who challenges them will likely be hauled before an appeal board and asked to explain how she has the temerity to tell students their papers are hastily compiled and undigested piles of drivel unacceptable as university-level work. The customer is always right. One university vice-president I know promises on her website that she will provide “one-stop shops” and “exceptional customer service” to all. Do not let the stupidity of this statement fool you into believing it is in any way benign. We no longer have “students”—only “customers.”

Online courses are perhaps one of the most complete expressions of the denigration of university education. At least half of all Canadian universities offer students some kind of online programming. The rise of technological pedagogies has, for example, brought us the “inverted classroom,” in which the typical lecture and homework expectations of a course are flipped. Video lectures (understood as the dispensing of “information”) are viewed by students at home before the class sessions. Class time is devoted to “just-in-time” lessons where students participate in “learning activities” and are remediated depending on how successfully they have acquired the proffered “information.” This type of curriculum was recently endorsed as a potentially effective strategy to meet contemporary students’ needs by the current University of Toronto vice-president and provost during an interview on CBC’s The Sunday Edition.

In contemporary classrooms, students and professors are like a married couple that have been separated for months but still live together for reasons of convenience. They don’t like each other and they’re not talking anymore, but they find it financially and socially expedient to continue cohabiting. Online courses mark the end of this arrangement, the moment at which even the pretense of conviviality is abandoned: the divorce papers are signed, and both parties pack their bags and head their separate ways. From then on, they email only, and only for the sake of the kids.

Increasingly, these courses are preferred even by students who attend the university full time and live on campus. Why go to class when you can watch a video online and then do a quiz? If your learning style is visual (i.e., you can’t read) and your range of concentration is fifteen minutes (i.e., you have no attention span), then you can watch the video in fifteen-minute chunks. And if you don’t like what you’re hearing, you can just turn it off and ask your friend about it later. And if you don’t understand what is being said, don’t worry. Who will know?

No one will ever ask you a difficult question that makes it apparent you haven’t done your readings; it is much easier to fudge online assignments or to plagiarize them outright; the assignments themselves will tend to be simplistic, multiple choice–style tests and quizzes that fit the technical structure of the medium much better than more complex forms of writing. All of this comes with the added perk, for professors, of not having to read long and often poorly written essays and reviews.

The older university administrative class, with its sobriety and appreciation of the real ends of the university, no longer exists. Instead, presidents and vice-presidents act like CEOs as they jet around the world and post pictures of themselves on their institutions’ websites cutting ribbons, shaking hands, and receiving clown cheques. They are also busy building around themselves large cadres of expensive staffers dedicated exclusively to serving, well, them. As money is siphoned from academic programs through attrition, it is channelled into a host of middle-management positions. For instance, in my university, there are some fifty-six employees in just three administrative departments—communications, student services, and the registrar’s office. And that is only the tip of the iceberg. To get a real sense of the staffing proportions, consider that in 2014 there were 516 permanent and contract staff members working for the university and 259 permanent and term faculty members. In other words, the number of those employed to support the work of the institution was more than double that of those employed to do the work of the institution.

Follow the money, and the proportions get even worse. Despite the rhetoric of large faculty salaries gobbling up precious university resources, the numbers tell a different story. According to 2013–2014 data from the Canadian Association of University Business Officers, the proportion of university budgets dedicated to faculty salaries dropped from a 32.1 percent share—already comparatively low—to just 29.4 percent. By comparison, the growth of the administrative set has been staggering. From 1979 to 2014, central administration and staff ballooned by three and a half times, while the size of the faculty merely doubled.

A business working on such a model might not necessarily go bankrupt, at least not right away. It might even prove, for a time, extremely lucrative for certain high-ranking executives and shareholders, as it was in 2008 and afterward for American banks. But, if assessed on its ability to generate and distribute real wealth, its emptiness and unsustainability become clear. In this way, universities are able to continue functioning because parents, students, and governments keep supplying them with capital, assuming there will be a genuine return on investment. But, since the institution no longer produces anything, no such return is forthcoming. Its “product”—cultivating intelligence and learning—has been abandoned in favour of far less demanding activities delivered by staff members who are amenable to the new ethos.

These are the “student services” personnel who are populating our universities in ever-greater numbers and draining our budgets. Student counsellors, academic program counsellors, recruiters, assistants to the recruiters, managers of the recruiters, program directors, program coordinators, program advisers, facilitators of academic success, project officers, curriculum support personnel, technologists—the list is endless. Spending on the student-services sector in Canadian universities increased an incredible six-fold between 1979 and 2014. Because such employees have achieved a certain critical mass, and because they work directly for, and find favour with, upper-level administrators, they are now a sector unto themselves, with their own agenda and power within the institution.

That agenda? As one of my friends put it to me recently, the student-services cabal is no longer there to support faculty in their work of educating students “but to compete with them to define the student experience.” And what is the experience they wish to define? Fundamentally, one in which students are made to feel happy, empowered, valued, and the centre of their own learning experience. The student-services department itself will guide students to this beatific end and shield them from cantankerous faculty (like me) who insist on raining on the parade by actually attempting to teach them something.

If you think I overstate the matter, consider this: I know of faculty members who have been summoned by student services staff members to “discuss” a grade with an unhappy student. Never mind that grades are not designed to make students happy but rather to encourage them to grow intellectually by setting goals just beyond their reach; and never mind that, as a matter of university policy, students are considered adults and, as such, are required to take their complaints directly to their professors. But, because the institution allows this to happen, student-services staff members are able to intervene in academic matters for which they have no qualifications. As a result of their actions, your sons and daughters may well feel happy and empowered and valued in their programs. What they won’t be, however, is educated.

There is a chorus of people these days telling my colleagues and me that our institutions of higher learning have never been healthier, that we are graduating more students in more disciplines in more technically advanced ways than ever before, that things simply couldn’t be better. How is one to respond to such claims?

Carefully, as it turns out, or else it’s the unemployment line for you. But not having to be polite when others are speaking shamelessly is what academic freedom was meant to protect. The UPEI collective agreement states that the academic freedom of faculty members guarantees their right to criticize both the university and their faculty association without fear of reprisal. When institutions go off the rails and forget their mandate, we are called upon to say so, clearly and unambiguously, and university administrators should listen. What happens instead? Gag orders, personnel disappearing without explanation, buyouts with hush money changing hands. In other words, if you exercise that right in order to protect the well-being of your students and your institution, you’ll likely not be around for very long.

At my university alone, we’ve seen the departure of some five vice-presidents, the university comptroller, seven deans, and a host of directors over the past four years. Why? No one knows because no one talks. But the effective truth of the situation prevails nonetheless—a sense of menace and fear rather than collegiality and open debate. Contract and sessional staff who speak up are, of course, completely vulnerable. But even tenured faculty members are not immune to various forms of pressure and harassment. Roadblocks to promotion, the shrivelling of departments through non-replacement of faculty positions, refusals of sabbatical applications—all these tools are available for the enforcement of conformity and the silencing of debate.

If you are mocked and denigrated for years on end, whether passive-aggressively through the slow clawing back of your budgets or through the Disneyfication of your course offerings (Religious Studies 211—“The Whore of North Africa: Augustine Gone Wild in Carthage”) by more “progressive” colleagues, sooner or later your rational self might tell you that the game is up, and you might stop doing what it is you do (serious study of texts and historical events, honest lectures with real content) and start doing what you are expected to do (keep an increasingly disengaged and intellectually limited group of young people entertained or otherwise distracted for three hours a week).

Though entirely understandable, this is a self-defeating strategy. You dumb down your lectures to keep your subscriptions up and to justify your courses in the eyes of the administration. The dumber they become, the less justification there is for continuing them and the more the administration sneers when it hears your defence of the ennobling powers of the humanities and the arts. So why wouldn’t you just go along? Why not inflate Susan’s and Bill’s grades to ensure that they have a nice experience and don’t feel disrespected? Why not indeed, if doing so comes with the added perk of avoiding catching hell from students and administrators for refusing to say that two plus two equals five?

Because the worst fate for our children, yours and mine, is yet to come. Because when the easy pleasures of youth run out and self-affirmation is all students have left, what will remain? Not just bad work and the dreary distractions of the modern entertainment industry—all of which can be tolerated, as bad as they may be—but the absence of something to live for, the highest and most beautiful activity of their intelligence. To cheat them of that is the real crime and the most profound way in which modern universities have betrayed the trust of an entire generation of young people.

This appeared in the April 2016 issue.

This article has been adapted from an essay published in the Los Angeles Review of Books on December 9, 2015.