There was a commotion by the library magazine rack. I assumed it must be about the Beatles—in February of ’64, Toronto’s Upper Canada College was abuzz with Beatlemania—but when I looked up, I saw an older boy I knew to be a smartass reading aloud to his pals from the latest issue of Maclean’s. Although I couldn’t make out what he was saying, one comment rose above the raucousness: “Men kissing—eeew, sick!” Eventually, a fifth former wearing a prefect’s tie came in and ejected the group. I waited until the room cleared before going to retrieve the offending magazine.

At thirteen, I was already a somewhat precocious Maclean’s reader, but here was an article unlike anything I had seen before. “The Homosexual Next Door,” by Sidney Katz, opened with a startling boldface subhead:

A million adult Canadians are homosexual. Some are “married” couples living quietly but well in suburban bungalows. Most of the others are ordinary citizens in all respects but the one that makes them criminals before the law and outcasts before society.

The article described a club for homosexuals, with over 700 members, that was flourishing on Toronto’s Yonge Street. Such a club operating openly, it noted, “underlines the rapidly changing nature of the homosexual problem.” The “problem” was that although Canadian homosexuals increasingly wished to live their lives in their own way, Section 149 of the Criminal Code made them outlaws. They were denied civil service jobs, private companies would often fire gay employees if their secret identities were discovered, landlords could refuse them housing, and most churches rejected their “wicked and evil” ways.

The wickedness of homosexuality had already been impressed upon me. To my parents, both devout evangelical Christians, the H-word described a terrible sin. “Homo” and “fairy” were ubiquitous schoolyard taunts in the 1950s and ’60s, even within the blazer-and-tie confines of an elite boys’ school such as UCC. A curious adolescent urban myth of the time held that Thursday was “Queer’s Day,” when anyone who wore green was automatically “queer” and ripe for teasing.

Despite the juvenile razzing, I don’t think any of us believed that someone we knew could truly be “queer.” The school’s music teacher was nicknamed Fairy, but to suggest that he might actually be gay was unthinkable. So Katz’s depiction of a secret world in which men kissed, danced, dated, and even “married” was both eye opening and shocking to a young teenager in 1964. I remember quietly describing the article to one of my dorm mates, who simply shook his head in disgust and walked away. His reaction confirmed Katz’s observation: “Most people are repulsed and frightened by homosexuality, so much so that they would prefer to ignore the problem entirely.”

In the piece, Katz described meeting a forty-three-year-old man he calls “Verne Baldwin,” who, in his view, “speaks for the newly militant homosexual.” (The article focused almost exclusively on men, since it seemed to Katz that lesbians were “less obtrusive and less discriminated against.”) “As the first step toward justice, Section 149 should be abolished,” Baldwin told Katz. “Nobody is harmed by two consenting adults who perform in private what comes naturally to them. We homosexuals are society’s remaining scapegoats.”

Baldwin was actually James Egan, a gay activist long before the term existed; in the Toronto of 1964, “the newly militant homosexual” was mainly Egan himself. He grew up in an Irish Catholic family, in the city’s working-class east end, and served in the merchant marine during World War II. “The war was exciting and thrilling for me,” he told Donald W. McLeod in Challenging the Conspiracy of Silence, a 1998 biography. As it did for so many others, the war showed Egan that he was not alone, introducing him to a clandestine world where gays met and fraternized.

After his return home in 1947, he began to navigate Toronto’s underground gay scene. He was attractive, with a lean, sinewy frame and a chatty manner, and he made friends easily. On one of his first visits to the Savarin Hotel, a gay hot spot, he ran into his younger brother Charlie, whom he hadn’t known was gay. A year later, also at the Savarin, he was instantly smitten by a boyish younger man named Jack Nesbit, who would become his life partner.

Largely self-educated, Egan read everything he could find about homosexuality, from Walt Whitman to Havelock Ellis to daring new works of fiction such as Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar. By 1949, he had begun writing gay-positive letters to magazines and newspapers under his own name, although most were never printed. Time magazine, for instance, ignored his objections to its use of the term “pervert” in reference to gays. He had more luck with the scandal sheets, true-crime tabloids that sold for a dime in cigar stores. In the ’50s, he persuaded two of them, True News Times and Justice Weekly, to run articles he had written that argued for greater tolerance toward homosexuality. By the early ’60s, the Toronto Daily Star and the Telegram were printing his letters calling for the amendment of the gross indecency clauses in the Criminal Code, which made homosexuality illegal.

These letters caught the attention of Sidney Katz, who at forty-seven had carved out a reputation at Maclean’s for edgy stories. In 1954, he travelled to a mental hospital in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, to receive an administered dose of a little-known hallucinogenic drug called LSD, an experience he described in his article “My Twelve Hours as a Madman.” He covered the 1955 riot in Montreal that followed the suspension of hockey star Maurice “Rocket” Richard; and wrote about racism in Dresden, Ontario, whose black community dates back to the Underground Railroad.

Katz himself grew up as part of a minority in white-bread Ottawa during the ’20s and ’30s, the son of a Russian father and a Lithuanian mother, both Jewish immigrants. During World War II, he served as a radar mechanic with the RCAF and later the raf, and in his wartime diaries he frequently despaired at the prejudices of the men at his remote radar station off Labrador. Sturdily built, with a mop of unruly black hair and an engaging smile, he had been courting Dorothy Sangster, a young woman from a large Catholic family in Ottawa. On leave in 1943, he eloped to Vermont with her, causing a permanent rift with his father for marrying a shiksa. Dorothy became a journalist, too, writing for Maclean’s, Chatelaine, Canadian Geographic, and other periodicals. At their home on a tree-lined crescent in North Toronto, the couple spent most evenings sitting side by side absorbed in books, or magazines such as Harper’s, The Atlantic, and The New Yorker, often reading passages aloud to each other.

Sid and Dorothy had two teenage sons: Stephen, who had always been unusually bright, creative, and articulate; and Jeremy, who was quieter, and more fond of sports than books. Despite the brothers’ differences, Jeremy recalls that his father never played favourites. “He was always fair minded—and always a champion of the underdog in his work,” Jeremy says. “He believed that a democracy is judged by how it treats its minorities.”

Sid Katz’s feelings for the underdog are evident in “The Homosexual Next Door.” Rereading it fifty years later, I was struck by how far ahead of its time it was—largely as a result of Egan’s influence. While researching both men, it became clear to me that the story of a remarkable social change in this country is woven through their two very different lives.

At their first meeting, Egan offered to give Katz a tour of Toronto’s gay haunts. Fifty years ago, there were no actual gay bars in Toronto, only hotel beverage rooms that, often grudgingly, allowed a gay clientele to gather there. Ironically, Ontario’s post-Prohibition laws required that single men be segregated from “ladies and escorts,” making it easier for some beer parlours to become gay establishments. Two of these were located in the Municipal and Union House Hotels, on adjacent street corners near Queen and Bay, and thus known in gay circles as “the Corners.”

On a Saturday in December 1963, Egan decided to start off his tour with Katz at the Corners early in the evening. “I didn’t want him to see them at eleven, when they were at their height,” he later told McLeod. Even in a quieter mode, the Corners still struck Katz as “two of Toronto’s lowest gay taverns,” and he noted that one “consisted of a long, shabby, depressing room.” He observed that most of the patrons were “masculine-type” gays, though he spotted a few drag queens, as well as a number of table-hopping youths—hustlers soliciting the older men.

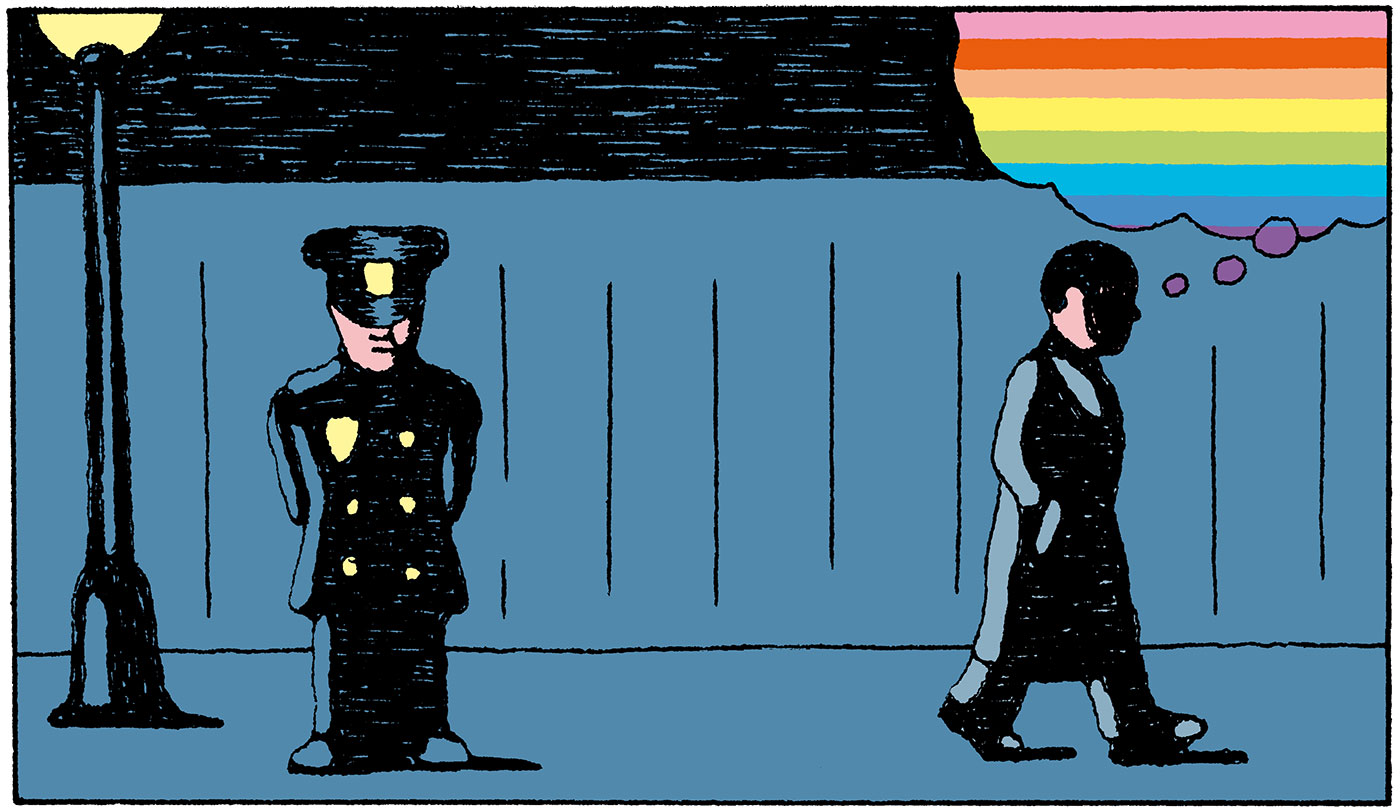

After a few drinks, Katz and Egan walked north on Bay Street, heading for the Ford Hotel near Bay and Dundas. Bay Street was rather dimly lit, and on the way Egan pointed out more hustlers standing in store entrances and alleys. He told Katz that when a male prostitute was arrested, he would likely receive a two-year jail sentence, while a female usually got off with a fine.

Soon, Egan spotted a man he knew named Fred approaching. “Oh, my God,” he thought. “Of all the people I’d want us to run into the last would be Fred.”

“Hi, Jim. How are you tonight? ” Fred asked in a lispy voice.

“Hello, Fred,” Egan replied. “Off to the Corners? ”

“Oh, yes,” he replied, eyeballing Katz (“like a coy girl,” in Egan’s words).

“And who is your most attractive gentleman friend? ” Fred then asked, causing Egan to “nearly shit,” as he told McLeod. In 1963, even Toronto’s most liberated homosexual was not beyond feeling embarrassed by the antics of a flaming queen in front of a Maclean’s journalist. Egan bade Fred a hasty farewell, and the two men resumed their walk.

The Ford Hotel, opposite the city’s main Gray Coach Terminal, likewise did little to burnish the image of gay life in Toronto. Its dingy beverage room was a hangout for hustlers, many just off the bus from Sudbury or Sault Ste. Marie, according to local gay lore. Egan ordered a beer but soon decided that they should head to the Red Lion on Yonge Street.

The place had English pub decor, and its more respectable atmosphere buoyed Katz. Looking around the packed room, he asked Egan, “How many of the fellows in here do you suppose are gay? ” When Egan replied that almost all of them were, Katz said, “Well, what is that idiot chief of police talking about, the way he describes a gay beverage room as some sort of den of iniquity with degenerate-looking people? I don’t see any fellow in here that I wouldn’t be proud to call my son, as far as personal appearance is concerned.”

Jim Egan was certain Maclean’s would be swamped by hostile letters once Katz’s piece ran. “I had visions of pulpits being emptied while all the clergymen rushed to their typewriters to dash off letters of bitter protest,” he later recalled. His fears were justified: Katz quotes a local minister thundering that Toronto had become “a modern Sodom and Gomorrah,” after a newspaper published a story about a gay club in the city. One letter to the editor, cited by Katz, asked, “How can the slightest tolerance be accorded to such bestial perversity? ”

Egan wrote a few letters under different pseudonyms to Maclean’s in praise of the article, though in the end they were unnecessary; the magazine only printed three responses, all fairly supportive. Yet the impact of Katz’s two articles (a follow-up ran in the next issue) on Canada’s closeted gay world was huge.

Before the first instalment even appeared, a friend invited Egan to lunch and introduced him to an older man who, as Egan told McLeod, seemed to be “just oozing money, position, and power.” The man had read some of Egan’s letters to the newspapers, and had heard about the forthcoming Maclean’s article. He urged Egan not to co-operate with Katz. “If you keep on publicizing this the way you are,” he said, “it won’t be possible for any gay man to be safe.” When Egan responded that he thought it would be great if every homosexual in Toronto could be brought out of the closet overnight, the older man looked at him with horror. In a world where exposure meant ruin, most gay men closely adhered to the omertà of silence.

“That Maclean’s article was enormously influential for a lot of people,” recalled the late John Alan Lee, a retired sociology professor. In 1964, he was a thirty-one-year-old married father of two living in a bungalow in suburban Don Mills, Ontario. His diary for that year documents the impact Katz’s writing had on him:

February 17. Jean [my wife] and I subscribe to Maclean’s magazine. This month’s issue contains an article by renowned Canadian journalist, Sidney Katz. “The Homosexual Next Door”.…Katz’s portrait of the “quiet and neighbourly unmarried man living alone next door” makes me wonder: is it possible for decent, functioning, even religious people to be homosexual? Could I be homosexual?

February 18. DAY OF DECISION. All morning in my office, I debated whether to contact Sidney Katz. Finally, I went to the pay phone at the street corner, put a handkerchief over the mouthpiece to disguise my voice, and called: “I want to find out if I’m a homosexual. Can you give me the address of the secret club you describe in your article? ”

February 24. Last Friday, I crossed into another country.…I told Jean at Friday dinner that I was going to a CCND [Canadian Committee for Nuclear Disarmament] executive meeting. Instead, I went to the address Katz gave me. An unmarked door led to a second-floor “club.” Petrified of what might lay inside, I parked my car in the side street opposite, and for an hour watched who entered.…Finally I mounted the long staircase.…This private club is called the Music Room. It’s a space several times the size of an ordinary living-room, decorated with flocked wallpaper and furnished with comfortable couches around the edges of a dance floor.…Both homosexuals and lesbians are welcome, and the atmosphere reassures: “You are in a safe place.”

Two days later, Lee told his wife that he thought he was gay. “You can’t be,” she replied. “We used to have very good sex.” That weekend, he took her to the Music Room. Within a few days, they agreed to try what Lee called “one of these new-fangled ‘open marriages.’” On March 29, six weeks after reading Katz’s piece, he had his first gay sexual encounter, with a “lean and whippy” young man he had met at the Music Room. According to his diary, “It was sensational.”

Two weeks later, while attending a meeting in London, Ontario, Lee read a nasty article in the Toronto Telegram about “the sick underworld” of the homosexual, and he fired off a vigorous rebuttal using the name “London sociologist.” (Following Maclean’s lead, the Telegram had decided to do a three-part investigation of Toronto’s “not-so-gay” world, portraying homosexuals as vicious pedophiles, crime magnets, and incubators for venereal disease.) By the early ’70s, John Alan Lee had embraced gay activism, and on Valentine’s Day 1974 he became Canada’s first openly gay academic, after outing himself on a call-in TV show.

Jim Egan had no further contact with Sidney Katz after the Maclean’s articles appeared, and later regretted not writing him a note of thanks. However, having recently separated from his partner, Jack Nesbit, he had other things on his mind. Their relationship had survived many challenges over the past fifteen years, including a failed experiment at raising pigs and turkeys on a rundown farm in northwestern Ontario. Egan’s activism was the primary cause of their split; the tipping point was an invitation for him to appear on a local radio show. Nesbit was a quiet homebody, and, like many gay men of the time, he just wanted to live discreetly with an affectionate partner. He thought that gays who ran afoul of the law brought it on themselves; Egan’s increasing visibility made him fearful that the police would come knocking on their door.

The newly single Egan visited the Music Room more often, and the club’s owner would occasionally ask him to counsel younger members who felt troubled about their sexuality. On Thursday nights, Egan began hosting an informal discussion group about gay issues. Sometimes, as many as sixty people would take part. A few years earlier, he had attended a conference in Los Angeles sponsored by ONE, an early American gay rights organization, and was thinking about starting a branch in Toronto. However, in May of 1964 he reunited with Nesbit, and the main condition of their reconciliation was that Egan give up his gay activism. The couple decided to start a new life together on Vancouver Island. In June, they bought a large truck, filled it with their possessions, and drove across Canada with three chihuahuas sitting on the seat between them. They moved to Duncan, in the Cowichan region, and set about establishing a biological supply company.

For the next twenty years, Egan kept his promise and refrained from involvement in gay causes; but when George Hislop, a friend from Toronto, wrote to him in 1966 about starting a gay organization in the city, Egan sent back a five-inch reel-to-reel tape filled with advice. Hislop went on to found the Community Homophile Association of Toronto in 1970 and became a leading gay spokesperson; today a park in Toronto’s gay village bears his name.

The term “homophile” was adopted by early gay organizations in an effort to take the “sexual” out of “homosexual.” In the fall of 1964, the largest American homophile group, the Mattachine Society, reprinted Katz’s two Maclean’s articles as a pamphlet. Their positive depiction of gay life provided a welcome alternative to “Homosexuality in America,” a two-part feature published in Life earlier that year. The photojournalism magazine, then a weekly staple in over eight million American homes, chose to illustrate its first take on this taboo subject with grainy black and white shots inside San Francisco leather bars, and images of gay men being marched off in handcuffs by the police. A large-print cutline proclaimed, “In a Constant Conflict with the Law, the Homosexual Faces Arrest, Disgrace.” One of the articles, purporting to cover the latest science on homosexuality, began by asking, “Do the homosexuals, like the Communists, intend to bury us? ”

Published five months after the Maclean’s articles, “Homosexuality in America” reads as if written in the McCarthyite ’50s, and it foreshadowed how much tougher the fight for gay acceptance would be in the US than in Canada. In fact, the very next year, an arrest in a remote mining town in the Northwest Territories would serve as the unlikely catalyst for this country’s decriminalization of homosexuality.

On August 16, 1965, an arson in Pine Point, Northwest Territories, prompted the RCMP to investigate Everett George Klippert, a mechanic’s helper at the local lead and zinc mine. He had no connection with the crime, but under questioning he admitted to having had sex with four men, and the police charged him with gross indecency. Assessed as “incurably homosexual,” Klippert was sentenced to indefinite detention as a dangerous sexual offender.

When both the Court of Appeal for the Northwest Territories and the Supreme Court of Canada dismissed his appeals, NDP leader Tommy Douglas raised his case in Parliament in November of 1967, questioning why homosexuality was a criminal issue. A month later, on December 21, 1967, Justice Minister Pierre Trudeau introduced Bill C-150, which included proposals to decriminalize homosexual acts between consenting adults over the age of twenty-one. In a media scrum afterward, Trudeau uttered what would become one of Canada’s most cited political aphorisms: “There’s no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation.” Despite fierce opposition from religious groups and the Quebec Créditistes—who called Trudeau “a beast of Sodom”—the bill finally passed on May 14, 1969. Klippert, however, would not be freed until 1971.

A few years earlier, Sidney Katz had left Maclean’s for a job as a feature writer and columnist at the Toronto Star. In a column on December 22, 1967, he expressed admiration for Trudeau’s reforms, noting that homosexuals might soon be allowed to live openly. By then, the issue held some personal resonance: in late August of 1967, after a summer working at Expo in Montreal, twenty-year-old Stephen Katz had told his parents that he was gay. They were accepting but concerned. Did Sid Katz imagine his son in one of the lowly gay dives he had visited with Egan only three years before?

Stephen soon became known as a director and designer in Toronto’s burgeoning early ’70s theatre scene. The director John Hirsch suggested that he move to New York, which he did in 1980 before returning to Toronto in 1985. Two years later, he was diagnosed with AIDS-related pneumonia. Sid and Dorothy cared for him as he went in and out of hospital, as did Stephen’s partner, Dwight Huggins, a former ballet dancer.

Always slight, Stephen shrank to a skeleton before dying on November 18, 1989. The family was devastated. At the funeral, seventy-three-year-old Sid delivered a heart-rending eulogy. “We respected him, we admired him, we treasured him, we loved him, and, as long as we live, we shall miss the pleasure of his company,” he concluded. Stephen’s ashes were interred beneath a headstone engraved with the comedy-tragedy masks and the inscription “Goodnight, Sweet Prince.”

Stephen Katz was just one of the many AIDS deaths that comprise what has been called “a lost generation in the arts.” The grim roster from Canada’s creative community includes film critic Jay Scott, dancer René Highway, conceptual artists Felix Partz and Jorge Zontal, and Stephen’s mentor, John Hirsch. When the epidemic first began, men with AIDS were shunned; but over time, AIDS accelerated gay acceptance, kicking open the closet door in a particularly cruel way. Some parents only discovered that they had a gay son upon being told he had AIDS. People who thought they didn’t know any homosexuals found themselves attending the funerals of colleagues and family members. Star-struck women wept for Rock Hudson.

AIDS also spurred the push for gay marriage. Painful stories from the plague years describe the partners of dying men being elbowed aside in hospital rooms and deprived of inheritances and insurance benefits. After the funeral for one of my friends, his family stripped his apartment of anything valuable while his partner lay dying in a back bedroom. AIDS made it clear that gay relationships needed recognition under the law.

On Vancouver Island, AIDS brought a return to gay activism for Jim Egan and his now supportive partner. In 1985, they founded the Comox Valley branch of the Island Gay Society and held meetings at their home over the next eleven years. During this time, Egan also volunteered with the North Island AIDS Coalition and served as its president.

On February 25, 1987, shortly before Nesbit’s sixtieth birthday, they filed a request for a spousal pension allowance under the Old Age Security Act. By then, Egan was receiving old age security, and had he been in a heterosexual union his spouse would have been entitled to a supplemental allowance, given their modest income. “It wasn’t about the money,” Egan said in the 1996 documentary Jim Loves Jack: The James Egan Story. “I wanted a hook on which to hang a constitutional challenge.” When the allowance was declined, as the couple expected, they commenced litigation, arguing that the opposite-sex requirement violated their equality rights under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The case was heard by the Federal Court of Canada in May of 1991 and dismissed in December. The Federal Court of Appeal heard a subsequent challenge, but ruled 2–1 against Egan and Nesbit in April of 1993. The appeal reached the Supreme Court the following year, and in a 5–4 decision the justices upheld the traditional definition of “spouse” in the Old Age Security Act. Egan and Nesbit were crushed; it seemed eight years of legal work had achieved nothing. Only later did they learn that their case had set an important precedent for gay rights legal challenges. Although the justices had ruled against the plaintiffs, they agreed unanimously that sexual orientation should be prohibited as grounds for discrimination under Section 15 of the Charter. Egan v. Canada would be cited frequently in later court cases, and today it stands as a landmark Supreme Court ruling on gay rights.

Over the next few years, Egan and Nesbit became a poster couple in the fight for same-sex marriage, and they appeared often on television. In Jim Loves Jack, the eighty-year-old Sidney Katz recalled Egan’s assistance with the Maclean’s article. “I’d never met a homosexual who admitted he was homosexual,” he said. “Jim was a delightful, daring man.”

On June 29, 1995, Egan and Nesbit served as the honorary marshals for Toronto’s Gay Pride Parade. Wearing pink shirts, they sat on the back of an open convertible while marchers held up a banner that read, WE ARE FAMILY GET USED TO IT. Behind a lesbian playing rainbow-striped bagpipes, they rode down Yonge Street, past the old sites of the Music Room and the Red Lion, while Mayor Barbara Hall, MPs, and cabinet ministers waved to the crowds and muscle boys gyrated on floats. Overwhelmed by a scene once beyond imagining, Egan looked at Nesbit. The two men embraced, then burst into tears.

Three years later, another touching encounter took place at the Toronto book launch for Challenging the Conspiracy of Silence, Egan’s biography. Donald McLeod invited Katz, and the old journalist greeted the aging activist for the first time in thirty-four years. McLeod recalls that Egan seemed frail, already showing signs of the lung cancer that would end his life less than two years later. He died at home in Comox, BC, on March 9, 2000; Nesbit followed him by a few months, passing away on June 23.

Unlike Egan and Nesbit, Katz lived to see gay marriage legalized in Canada. On July 20, 2005, it became the first country in the hemisphere, and the fourth in the world, to allow same-sex partners to marry. “My dad followed the news on this,” says his son Jeremy, “and I know he was pleased that the law and society were catching up with people’s lives.”

Katz also drew rightful satisfaction from knowing that his writing in Maclean’s was considered an milestone in the movement toward gay equality in Canada. Reflecting on it for Jim Loves Jack, he noted, “Somebody has to do something for the first time. The problem before was that the subject was never discussed. If homosexuality was brought up it was always in connection with some crime—it was never related to ordinary life, to ordinary human beings. And once that was done in a national magazine—a very respectable family magazine—it became easier for other people to do it.” Katz died on September 13, 2007, at ninety-one.

Today gay marriage still bedevils our neighbours in the US, where homosexuality was not officially decriminalized until 2003. Seventeen states have legalized same-sex marriage, while twenty-nine prohibit it in their constitutions and four have passed statutes against it. (Courts in five states recently found gay marriage bans unconstitutional, and these rulings are under appeal.) Although a majority of Americans now view same-sex unions favourably, the opposition fights on fiercely. To Canadians, this debate seems suffused with déjà vu; it has been over a decade since the first gay marriages were performed here. Among those under thirty, support for gay marriage now polls in the 80 percent range. While reports of school bullying and teen suicides show that homophobia is far from a spent force, the progress that has occurred since 1964 is astonishing.

In February of 2013, a teenage boy at Upper Canada College named Ryan Stevenson stood in front of the assembled school while the word “faggot” flashed on the screen behind him. As president of the school’s Gay Straight Alliance, he was making a presentation on defamatory words in preparation for the club’s second annual Pink Shirt Day, when students celebrate gay positivity by wearing pink T-shirts. At the end of his speech, Stevenson announced to the school that he was gay. A moment of surprised silence followed. Then three of his friends stood up and applauded, and the entire school rose to give him a standing ovation. Some of the teachers were in tears.

On reading about this in the UCC alumni magazine Old Times, I tried to imagine a student coming out during my time at the school, but I could not; it would likely have resulted in instant expulsion and psychiatric counselling. The article about Stevenson still managed to raise some greying eyebrows among the older Old Boys. Yet today even the stodgiest UCC alumnus would likely agree that it is a good thing that no thirteen-year-old at Upper Canada College, or anywhere else in the country, will read in a national magazine that homosexuals are “criminals before the law and outcasts before society.”

This appeared in the June 2014 issue.