From the sky, Canada’s capital looks like a city on the edge of nowhere: an urban pocket surrounded by forests, farms, and a confluence of meandering rivers. Officially, metropolitan Ottawa takes up 2,790 square kilometres of space—more than four times the geographic size of Metro Toronto and roughly six times the Island of Montreal. The capital stretches from the sparsely populated pasturelands in the northwest to a bird sanctuary and creek in the east and a Victorian hamlet complete with a rickety wooden bridge to the south. Enter the city limits from any which way but north, and you won’t see hints of a city at all. What we call Ottawa is mostly greenbelt, sprawl, and farms—all of it unceded by the Algonquin, who lived here long before an English army engineer showed up, turned some sod near the current site of the Chateau Laurier, and began rerouting the region’s waterways.

The Rideau Canal was the city’s first rapid transitway, a 200-kilometre-long system of lock gates and hand-cranked swing bridges that linked what was then just a small logging town to the St. Lawrence River and the world beyond. Ottawa’s citizens have been taught to view the canal as an engineering marvel, integral to the city’s function and founding. Yet, upon its completion back in 1832, the canal and its concrete banks were considered by many a complete disaster. Its central architect, Colonel John By, was unceremoniously recalled to London, stripped of his commission, vilified in the press, and subjected to two government inquiries. When he was first assigned to oversee the construction, the colonel told his overlords in London that he could have the transitway operational in four years. It took him five. An estimated thousand labourers died under his authority. As upsetting as the death count was, the cost was the real sticking point back in London. The colonel had been given a budget of £62,258 (roughly 14.8 million in Canadian dollars today). By the time the transitway was operational, he’d spent more than fourteen times that. The results were so underwhelming to British eyes that the canal’s initial champions no longer understood why they had even commissioned it to begin with.

Times change, but many things in Ottawa don’t. Nearly 200 years after being founded as the northern terminus of an ambitious yet accursed transit project, the city is more than eleven years into a $6.7 billion civic calamity once promised as a “world-class transit system” but which—with the help of two train derailments, one monster sinkhole, countless engineering failures, and general bureaucratic ineptitude—has become a local disgrace and a national joke. It has triggered the fall of several politicians, tainted the legacy of Ottawa’s longest-serving mayor, and prompted a public inquiry that culminated in a damning doorstopper of a report. And the project’s not even halfway done.

After reviewing the minutes of committee meetings and council meetings, public testimonies, official submissions from the city and from the private sector, press reports, and the inquiry report itself, it becomes clear that the tragicomedy of the city’s light rail transit system is not just a cautionary tale about human folly—though that message is hard to miss. Nor is it simply a warning about how not to build a transit system—though that lesson is worth heeding. What Ottawa experienced should chill every municipality in every jurisdiction in Canada and abroad. This is what happens when a city that dreams of becoming more than it is meets the crushing reality of how cities are actually run.

Almost three quarters of Ottawa’s commuters drive to and from work. They clutter up roadways in their cars, trucks, and minivans in the predawn hours and late-afternoon rush. In the years before COVID-19, roughly 20 percent of working residents used OC Transpo, the city’s public bus system, to get to work. During the pandemic, that number dropped to 10 percent. Per capita, Ottawa now has some of the lowest ridership numbers of any city in the country, and it’s not uncommon to see nearly empty buses motoring around all day.

There is, however, one group that rides those buses: bureaucrats. About 10 percent of Ottawa’s residents work for the federal government. Though many public servants can implement, regulate, and administer policy from home as a result of the pandemic, those who venture to the office make up a bulk of the daily ridership on the 1,024 OC Transpo buses that routinely head out to the brown, grey, and taupe government buildings that blight the region. So it’s not hard to imagine that it was mostly for these bureaucrats and for their children, and for their children’s children, that local politicians began dreaming, as far back as 1997, of creating a more inviting, if not a bit more inspiring, transit system.

In 2010, councillors decided to take concrete steps. They believed that, with a $2.1 billion investment, they could convert their rapid transit system from bus to light rail. In so doing, they would undertake what, at the time, was the costliest infrastructure project in Ottawa’s history and create one of the most ambitious LRT networks on the continent. Though not technically a subway, the LRT would have subterranean elements. A two-and-a-half-kilometre tunnel would be dug under the Rideau Canal and the city’s core. Most of the track would run through a custom-built transit trench, over bridges, converted roads, and industrial land. It was a vision that played well with voters, especially those residents who used OC Transpo and who were excited at the prospect that they might never again have to spend their mornings and afternoons waiting in the cold for a bus that never seemed to arrive on time.

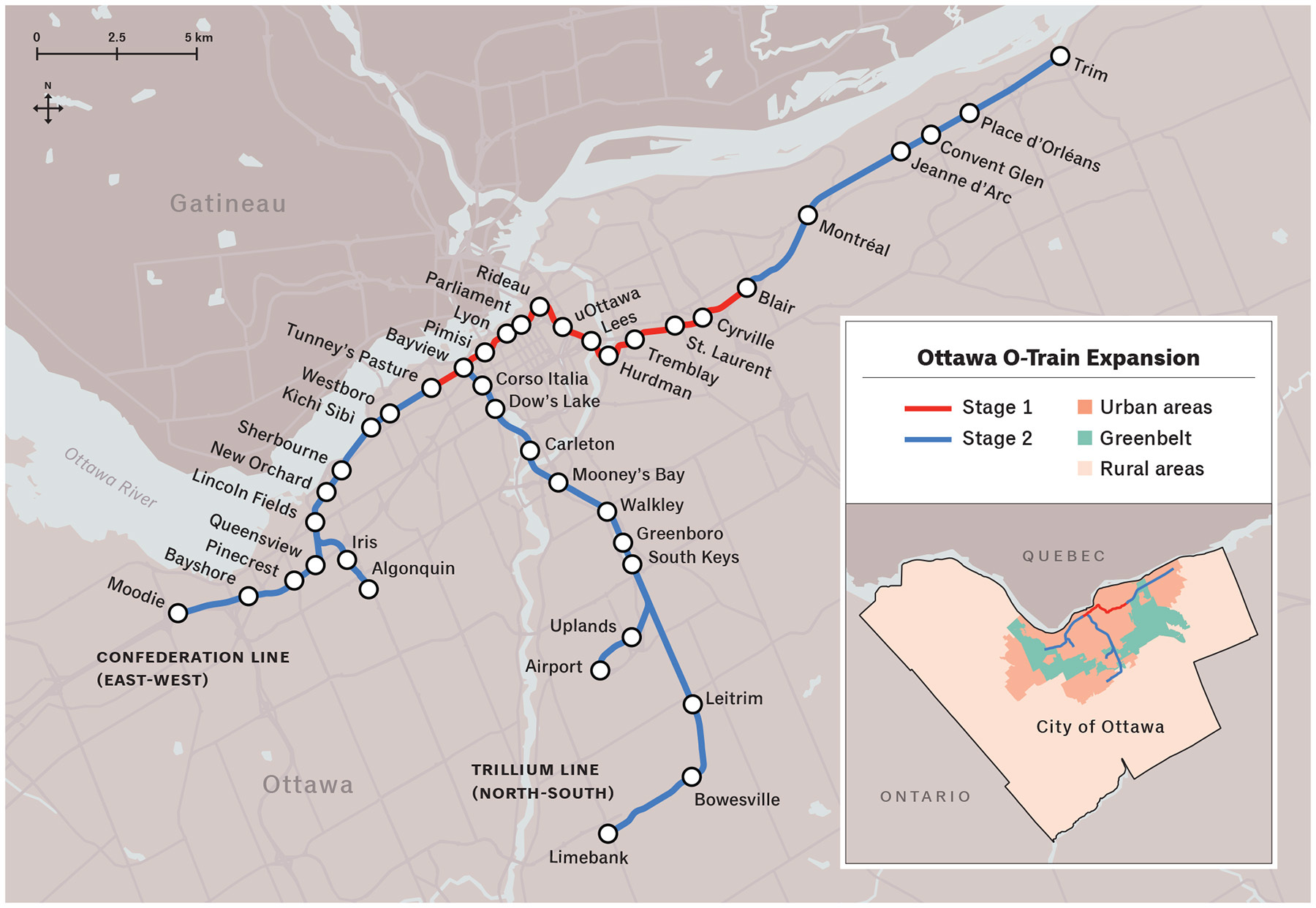

There would be two main train lines. The first would be the Confederation Line, a name that evokes the Canadian Pacific Railway that took just four years to complete, between 1881 and 1885, and which linked Ottawa to the Pacific Ocean, fulfilling a promise and precondition of confederation. It would replace part of an old bus route, beginning above ground in the suburbs, and then go under the downtown core, past Parliament Hill and under the Rideau Canal, before reemerging and carrying on toward more suburbia to the east of the city.

The Confederation Line would be built in two stages. Construction of Stage 1 would begin in 2013 and would entail twelve and a half kilometres of new track and thirteen stations. Because the City of Ottawa didn’t have the necessary in-house expertise required to design, construct, and maintain the LRT, it signed a multibillion-dollar, multiyear contract with Rideau Transit Group, a consortium of national and international engineering firms that then signed subcontracts with other firms to take care of the daily operations of the system. The arrangement between the city and RTG is known as a public-private partnership. There was precedent for this approach. In recent years, governments have ceded control over large infrastructure projects to private partners in an effort to control costs and cut through bureaucracy. By teaming up with RTG, Ottawa’s leaders thought the city would get its trains up and running on budget and on deadline. The partnership also meant the city wouldn’t assume the risks associated with the project. Under the agreement, RTG was to deliver a fully functional LRT at a fixed price and maintain it for thirty years. As part of Stage 1, the city would receive seventeen entirely new, all-electric trains. Designed by a French company and assembled in Ontario, the trains would be tailor-made to run on those twelve and a half kilometres of track. The project would then move to the more expensive Stage 2, adding forty-four kilometres of track and twenty-four more stations to the east, west, and south of the city at a cost of $4.6 billion.

That’s when the second line in the system would be built. They called it the Trillium Line. It would run north–south, repurposing portions of an old Canadian Pacific track, some of which was already being used by OC Transpo, which had begun running diesel passenger trains back in 2001. As part of Stage 2, an eight-kilometre stretch of track would grow to twenty-four kilometres, and the old diesel O-Trains would be decommissioned and replaced by new diesel trains produced in Switzerland that would each be eighty metres long and capable of holding 420 passengers. Unlike the Confederation Line, the Trillium Line would remain a heavy rail line, and the Swiss trains selected for it were chosen, in part, for their service record in climates ranging from the Arctic Circle to Africa. The trains would ultimately run under the man-made Dow’s Lake, through Carleton University, across the Rideau River, and all the way to Ottawa International Airport.

In pitches to the future ridership of Ottawa, then mayor Jim Watson championed the system as something that would be envied by cities all over the world. It was expected to be more modern than Montreal’s Metro, faster than Toronto’s streetcars, and would rival Vancouver’s SkyTrain for the number of stations. Ottawa wanted the LRT to have the capacity to carry 24,000 passengers per hour in each direction, a feat in line with what subways are capable of achieving. But the trains were just part of what would make the system special. The stations would be designed to stand out like individual architectural statements and would feature permanent art installations by the likes of Douglas Coupland. When it was all put together, the LRT would give Ottawa more of that capital-city charm. London had electric trains. Paris had electric trains. Even Canberra was going electric. Now it was Ottawa’s turn.

On a frosty Wednesday in December 2012, councillors cast what they heralded as a historic vote that would finally see Ottawa take on the aura of a big city. One councillor invoked The Little Engine That Could, saying that, with the LRT vote, Ottawa was graduating from a “we wish we could” to “we think we can” mindset. No one knew then the myriad ways it would go off the rails.

Just a month after its launch, the beleaguered system had been branded a disaster and a joke on social media.

On Saturday, September 14, 2019, an exultant Mayor Watson walked alongside Ontario transportation minister Caroline Mulroney down a gleaming platform in a freshly opened station, admiring an LRT train filled with potential voters. It was the day of the LRT’s first official ride. Watson waved at passengers inside a white train with a big red maple leaf wrapped around its nose. Called the Citadis Spirit, it looked like it had just punched through the Canadian flag. He hopped on, and soon the train pulled out of the suburban station and began rolling toward the city. That inaugural ride complete, he tweeted out: “Our city now has a world-class transit system. Congrats and thanks to everyone who made this dream a reality. ALL ABOARD.”

The train cars that carried Watson and his fellow passengers that day were already fifteen months behind schedule, as the LRT line was supposed to open in May 2018. The project had been plagued by a series of human-error and engineering calamities, but maybe the single biggest cause for delay was a multi-hundred-million-dollar sinkhole that emerged around 10:30 a.m. on June 8, 2016, on one of Ottawa’s busiest downtown streets. There was no advance warning that morning as light rail construction crews tunnelled under the historic Rideau Street near its intersection with Sussex Drive.

An OC Transpo bus had just driven over the intersection. Minutes later, the earth gave way, swallowing a minivan as well as several traffic lanes and portions of the sidewalk. According to a CBC report, it took weeks to pump water out of the tunnel and safeguard the area against further collapse.

There were no injuries, but the partnership between the city and RTG was left irreparably damaged. The city blamed the contractors for errant tunnelling, while the contractors blamed the city for having improperly installed a joint on a relocated fire hydrant, resulting in soil erosion. Antonio Estrada, RTG’s then CEO, later testified that, post sinkhole, the city had little patience for delays. Every time RTG blew past a deadline, its relationship with Ottawa further crumbled. By June 2019, the city’s own consultants had warned the system was still unfit to be opened to the public. Outside assessors had awarded the system’s overall readiness a three or four out of ten. As problems cropped up with the trains’ electrical and mechanical systems, the contractors began lobbying the mayor’s office for a soft launch. Frustrated after more than a year of waiting, the city insisted that all trains be operational on day one.

One of the costliest errors in executing that launch was the decision, made by city officials against the advice of industry experts, to approve a train design that had never been used anywhere else on the planet. The city had made several demands of the LRT vehicle. Aside from wanting it to be accessible, fast, and zero emission, they also needed a system that could fit the already-decided station length, which meant the trains would have to be longer than those in any other LRT in operation in North America. Alstom, the French manufacturer, knew that whatever it produced was going to push the limits of what a light rail car could do. Alstom took its initial cues from a fast and versatile tram-train used in Nantes, France. But that design had to be modified to meet North American electric rail standards and to survive in cold weather, which can slow the flow of lubricants and disable vital electrical systems, causing metal parts to snap. So Alstom pumped the tram with winter technology from trains used in Sweden and Russia. To give it more power, they plopped in the same engine used in New York subways. By insisting that they be given a train that didn’t yet exist, Ottawa’s leaders guaranteed that the city’s residents would serve as test subjects on board what the public inquiry would call “unproven technology.”

As the inquiry would later reveal, a handful of Ottawa officials present during the September launch were withholding the fact that the fleet hadn’t met the city’s most recent standards for reliability. There were issues with the brakes, voltage, and auxiliary power. During testing, train operators had additional concerns. The cabin lights wouldn’t turn off, creating a glare that impacted drivers’ vision at night. The locks on the doors to their compartments looked to them like they had been cheaply purchased from Amazon. The doors themselves were also cause for worry. They needed a software update to function properly. Moreover, engineers were convinced that the track gauge was narrower than they’d anticipated, meaning the tracks were literally too close together, adding undue stress to the train wheels. As if to sum up the mood, a fecal stench began to fill the downtown tunnel.

The city’s explanations for the smell kept changing. After the first few weeks, they thought it was being caused by a broken sump pump in an escalator pit that had triggered a moisture buildup. A few months later, they said a sewer line must have been punctured during construction. At one point, a councillor took to Twitter to reassure the public that it was still safe to breathe on one of the stations in the tunnel. “RTG has completed tests of the air quality,” he wrote. “There is no risk to our customers or staff.” No one seemed impressed. “It’s reasonable to expect #LRT stations not to permanently smell like a toilet,” someone tweeted. Another chimed in: “Of all the complaints about #OttawaLRT the one I’d not have believed a year ago would be: ‘LRT Stinks! Literally smells bad.’”

On October 8, 2019, about three weeks after the launch, a passenger at the uOttawa station tried to hold a door open while getting off the train. The door jammed open, and the train couldn’t depart. Within minutes, trains in both directions were forced to share a single track, slowing down service dramatically during peak time. Hundreds were stranded. Images of hordes stuck in stations appeared on social media. At least one person jumped a fence to get away from the chaos. That morning, as commuters schlepped their way into work on foot, an aggrieved Watson began pressing city staff for answers. A staffer relayed the mayor’s questions to a group chat that included then city manager Steve Kanellakos as well as John Manconi, OC Transpo’s general manager at the time. Among the flurry of messages was Watson’s plaintive query: “We need more info on doors: why are they so sensitive, and why do drivers not have authority to override?”

In the months leading up to the launch, key city personnel, including the mayor, Kanellakos, and Manconi, had all begun communicating via WhatsApp. Watson used the channel to demand information. When contractors asked for more time to prep the trains before launch, Manconi assured the group via WhatsApp that he had solved the problem and that the contractors’ “blood [was] all over the boardroom floor.” In other messages, Manconi, a career bureaucrat who got his start inspecting backyard drainage systems in one part of the city and rose to head the entire public transit system, called RTG and Alstom officials “clowns,” “idiots,” and “morons” on separate occasions. Later, Manconi used the channel to vent after local media began highlighting the many service disruptions, lamenting that one vocal critic on radio was “destroying us with misinformation.”

By the end of October, some of the city staff were beginning to break down along with the trains. “Mr. Mayor I beg you,” Manconi wrote in the WhatsApp group. “Please, I am getting so many messages from you on multiple channels and your staff. I will answer [every one] of them. The service is running well . . . We are drowning in message overload.”

The mayor wasn’t the only one flooding the system. Anytime anything went wrong on any train or on any part of the system, the city or RTG subcontractors issued a work order. According to a maintenance executive, 900 such orders were issued in September 2019 alone after city employees were handed control of the Confederation Line and began looking for faults. The volume of problems quickly overwhelmed the small team at Rideau Transit Maintenance, the subcontractors tasked with keeping services operational.

Mario Guerra, acting CEO and general manager of RTM, told inquiry examiners: “They were picking on just every little thing out there. Most of it, I don’t think, was of a relevant nature.” To cope with the work orders, Alstom brought in support from Europe. But it never seemed like they caught up with maintenance problems. As performance woes mounted, the city began holding back payments, which only aggravated the already adversarial relationship between the city and RTG. Just a month after its launch, the beleaguered system had been branded a disaster and a joke on social media. Then, on November 1, 2019, the mayor and his colleagues got a 6:45 a.m. WhatsApp message from Manconi, alerting them that a switch failure was likely to cause service disruptions that morning. By 7 a.m., Watson’s texts appeared increasingly frenzied, demanding that buses be reinstated to run alongside the rail tracks.

“We need parallel service brought back,” Watson wrote. Suddenly the city was moving backward. The LRT, which was meant to replace the outdated, gas-guzzling bus system, had become so unreliable the city needed replacement buses to do the job that the new trains couldn’t. “How do we make this happen?” wrote Watson. “Our reputation is in tatters. Please tell [me] how we bring it back. I’m not concerned about costs at this point. I need reasons how we bring it back as opposed to why we can’t.”

Before long, Manconi was decrying a “total gong show out on the rail line this morning,” and on November 12, Watson sat on a slow-moving train, firing off irate messages to city staff, pinpointing innumerable frustrations with the quality of service.

“Just heard an announcement that we are on bus service,” he wrote. “What’s [the] problem?” Three minutes later: “How fast till it gets fixed?” Five minutes after that: “What is [the] cause? When will trains be fixed?” One minute more: “It is cold out. We better have buses ready.”

A few weeks later, the city had twenty idling buses sitting in a baseball stadium parking lot, ready and waiting to be called into action whenever a train stopped working. Then winter struck, and it became clear that the trains struggled in temperatures below minus twenty-five degrees. The city needed vehicles that could function in minus thirty-eight degrees and plough through snow, ice, and salt. But they also needed to withstand the capital’s muggy, humid summers. In truth, the multimillion-dollar bespoke design could handle none of it. (According to Alstom and RTG, the trains were tested during the construction phase to satisfy the contractual requirements set forth by the city.)

In January 2020, it was revealed that the wheels on the trains were no longer exactly round. It took some time for engineers to trace the problem to an overzealous braking system that ground wheels down in bad weather. There were other problems, too, that winter. On January 16, an overhead cable fell onto a train leaving St. Laurent station and caused a fifteen-hour service disruption. By mid-February, parts had fallen off a moving train and been knocked into transponders, taking four other trains out of commission. Manconi reportedly messaged members of his transit team to say that the mayor was losing his mind.

When winter slowly gave way to spring, relief for the LRT system came in the form of the pandemic, which sent thousands of commuters home and allowed the city and RTG to lower the number of trains in service. Then climate change heated things up again. In May and June 2020, unseasonably warm temperatures caused sections of the track to buckle. The following summer, a new level of panic set in: trains began to literally jump the track.

The first time a train derailed, no passengers were on board. It was a cloudy Sunday evening in August 2021. The train had been taken out of service five and a half hours earlier after triggering multiple warnings that, as it made its way east along the Confederation Line, its wheels were slipping on the tracks. The driver parked on the north platform of Tunney’s Pasture station, and a technician eventually cleared the train to continue toward the maintenance and storage yard. As the train travelled, a wheel skidded off the rail. The train ground to a halt, and the entire LRT system was shut down for five days.

For weeks, everyone from RTG to the Transportation Safety Board of Canada tried to piece together the cause. They found a broken axle and a melted roller bearing inside the wheels. Early investigations by Alstom seemed to blame the LRT track builders. They said the track design had caused undue stress on the wheels, leading to axle failure. Train wheels now have to be checked every 7,500 kilometres, or every 600 trips down the twelve-and-a-half-kilometre track.

The second time a train derailed, it had twelve passengers on board. It was September 19, 2021. The incident was caught on camera and happened shortly after the operator called in to report a “human waste smell.” Technicians in the LRT command centre were trying to identify the source of this odour when passengers on board began hearing noises underneath the carriage. Coincidentally, the director of maintenance for RTM, Steven Nadon, was on the train, joyriding with his wife and grandchildren, as it pulled into Tremblay station in the city’s east end. He later told investigators that he had heard a “sound beneath me and I thought a cable had come loose, or something was dragging.” Convinced the train would be taken out of service, he told his wife they needed to get off. Seconds later, standing on the platform with his family, he called the transit operations control centre to describe what he’d heard. He then watched, aghast, as the train pulled out of the station, wheels off the rails. It travelled that way for 427 metres, destroying a railroad signal post and a switch heater before the damage triggered the emergency brake. The train careened to a stop. No one was hurt.

This time, the trains were taken out of service for two months. OC Transpo replacement buses picked up the slack while maintenance crews and engineering experts tried, yet again, to figure out what had happened. The derailment was ultimately blamed on maintenance staff who failed to properly torque bolts when reattaching a gear box earlier that month. Somehow, the train managed to travel 800 kilometres before the bolts caused the wheels to skip the track. The trains didn’t start running again until November 12. For the last month of the year, the city wasn’t even willing to charge customers to ride the rails. The service was just too erratic.

As half-empty trains moved cautiously up and down the Confederation Line track, city officials notified the consortium that it was now in default on its side of the agreement. The city argued that RTG had “failed to meet the basic performance and service level metrics set out in the (project agreement).” Toothy letters ensued as city officials placed responsibility for the breakdowns squarely on their partners in the private sector. “The derailments have caused severe reputational harm to the City and to the system,” one senior bureaucrat wrote to the RTG CEO. “RTG does not appear to appreciate the gravity of the current situation given its refusal and/or inability to implement swift and appropriate actions with adequate levels of resourcing.” The city then filed a lawsuit against RTG, in a clear attempt to build a case to break its thirty-year maintenance contract.

As both sides geared up for a prolonged legal battle, Watson tried to keep the city’s clash with RTG from triggering a judicial inquiry. In November, he wrote to Mulroney, requesting “a fair opportunity to brief (her) more fully on this important issue.” His pleas didn’t work, and the province, which had bankrolled the LRT to the tune of more than $1 billion, ordered that a commission be struck to look into the debacle.

On December 10, 2021, Watson announced that he would not seek reelection, claiming that he had always planned to retire. Seven days later, the Ottawa Light Rail Transit Public Inquiry was officially established, led by justice William Hourigan, a long-time lawyer who specialized in commercial litigation before his judicial appointment in 2013. Meanwhile, in a virtual gathering of the city’s finance and economic development committee, Michael Morgan, the city’s rail construction director, informed councillors that Stage 2 of the project—the stage always expected to be more complex, more costly ($4.6 billion in total, more than twice the cost of Stage 1), and ultimately more important to the city’s economic future—was likely to be delayed a further two years. Morgan said there had been “further slippage” in the construction schedule and explained that crews trying to dig a tunnel under the Sir John A. Macdonald Parkway were seeing deeper clay than expected. Out by the airport, workers assigned to clear some forest, build an overpass, and flatten out marshland were now blaming ongoing physical-distancing policies for hampering their progress.

During the Zoom call with Morgan, some councillors shook their heads, others just nodded along. A couple stared blankly. Then a councillor who had been waiting to speak raised her virtual hand. “Delays or no delays, I am adamant that the city not take over any pieces of the extension whatsoever until we are absolutely confident that it is functional,” she said.

It took six months for Hourigan and the twenty-two members of the commission to prepare for public hearings into the commercial and technical circumstances that led to the Stage 1 breakdowns and LRT derailments. The commission combed through countless documents and conducted interviews with dozens of witnesses, including weary passengers and experts on public-private partnerships. The city tried but failed to block roughly 1,600 documents from reaching the inquiry, arguing the material, which included fifty-four pages of WhatsApp texts, contained information too sensitive for the public. Hourigan stated in his decision on the matter that the city’s application was “wholly unsupported by any compelling factual or legal basis.”

The public hearings began on July 13, 2022, and stretched over eighteen days. On each of those days, Hourigan and the commission gathered in a room inside the University of Ottawa, talking, both online and in person, to transportation experts and executives located on several different continents. In all, forty-one people testified, presenting a range of evidence and opinion on what the City of Ottawa and RTG did or didn’t do. Midway through the inquiry, it emerged that the LRT project had been so rushed that the French transportation company didn’t have time to examine Ottawa’s labour expertise to make sure there were people in the city who could actually build the rails correctly. The lack of local expertise became an even bigger problem when the company learned that the trains would have to be assembled in Ottawa in order to comply with provincial law—a situation that, Watson later claimed, “hobbled us from the beginning.”

The hearings complete, Hourigan and his team deliberated. In late July, storm clouds had gathered over Ottawa, releasing a lightning bolt that downed 900 metres of wire that ran over the tracks, setting the roof of one of the trains on fire, grounding another to a halt, and leaving the entire system offline for four days. Some said the lightning bolt was a sign from God that the people of Ottawa would never get the transit system they were promised.

On November 30, 2022, Hourigan released the results of a roughly $14.5 million inquiry. The 637-page document was so salacious and damning that one local columnist called it “a policy wonk’s version of a Stephen King novel.” In the report, Hourigan said both the city and its private sector partners committed numerous “egregious” errors. He recommended, among other things, that the tracks be torn up. He decried RTG and its construction partners for providing delivery dates they knew were unrealistic. “It is evident that this was done as part of a misconceived scheme to increase commercial pressure on the City,” he wrote. “As a commercial tactic, it was a failure because the deliberate communication of unachievable dates did nothing to improve RTG’s commercial position with the City. To the contrary, this gambit only served to increase and accelerate the mistrust that was developing between the parties.” (The City of Ottawa was not able to respond in time for publication.)

Hourigan saved some of his harshest criticism for Watson, Manconi, and Kanellakos, who he said knowingly withheld information from city council, especially in the lead-up to the initial launch when they used their WhatsApp group to discuss “critical information,” including a decision to lower testing standards for the LRT system.

“[B]ecause the conduct was wilful and deliberate,” Hourigan wrote, “it leads to serious concerns about the good faith of senior City staff and raises questions about where their loyalties lie.” The judge’s conclusions raised questions over whether the city could be trusted to oversee such a massive infrastructure project again. But, by then, many of the city’s upper brass had already resigned.

Manconi was the first to go. He retired as head of OC Transpo shortly after the second derailment in 2021. Mayor Watson was next. On November 14, 2022, the man who had staked his reputation on the LRT project left office after nearly three decades in politics. That afternoon, as Ottawa’s longest-serving mayor walked out of City Hall for the last time, sirens could be heard across town. Firefighters were speeding to an LRT construction site, where a crane being used to build one of the overdue stations had caught fire after taking out a power line and leaving 2,300 hydro customers without electricity. Two weeks later, Kanellakos issued a shock resignation, leaving a job that paid him more than $370,000 a year (nearly twice the salary of the city’s former mayor). “No one asked me to leave,” he said in a note to city staff. “I’ve always deeply believed in leadership accountability.” Two days later, Justice Hourigan released his findings.

When asked for comment, Watson referred The Walrus to his public statement, released ten days after the inquiry report, in which he took “full responsibility for the project’s shortcomings.” Kanellakos responded to the magazine by saying: “I have not comment[ed] publicly on Hourigan’s report up to this point and I will not be commenting on [it now].” Manconi did not respond to multiple requests. None of them hold public office anymore, nor are they affiliated with the city, but the construction of the project they once oversaw continues into its tenth year.

When they are not in the shop, the French-designed trains try to run up and down the twelve-and-a-half-kilometre stretch of the Confederation Line track. Despite all that has happened, there is still some appeal to the system as a whole. The underground platforms no longer smell of human detritus. The cameras that allow operators to see whether there are passengers hanging out of any train doors went out of commission a while back. For several months, human spotters stood on the platforms, whistling before the trains could move. It gave the whole thing an old-fashioned charm, kind of like the Rideau Canal. There’s still a tremendous amount of work to be done before the full system is operational in 2026, not the least of which is renaming the lines and some of the stations. Beyond the ends of the current twelve and a half kilometres of track, construction crews continue to dig through clay in the city’s west end, inching ever closer to their final destination. Out in the east end of the city, the steel frames of new stations are beginning to poke out of the ground. Meanwhile, freshly laid tracks can be seen from the sky around Ottawa International Airport.

After multiple delays, the director of Ottawa’s rail construction program says that, soon enough, passengers will be able to board a serviceable train from the city to the airport. (According to the city’s contract with developers, the airport link was supposed to open in 2022. It did not.) The prospect of using the LRT to travel to the airport and fly out of this town may give some residents something to look forward to. But it will be a long time before what’s been built seems like anything more than a disaster.