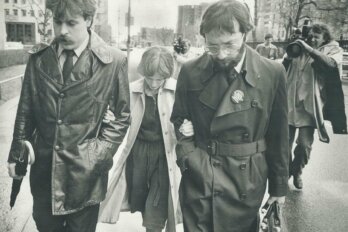

One evening last summer, as I walked home through downtown Toronto, I noticed a young woman, flanked by two men, lurch suddenly and unsteadily toward the man at her left.

Is everything all right? I asked her. The man to her right shrugged and waved me off. I exchanged glances with another passerby—I’d later learn his name was Henry—who’d also stopped out of concern, and we silently agreed that something wasn’t right.

Henry and I asked her whether she needed help getting home. The man to her right threw up his hands, declared that he’d had enough of this and walked away. The other man, who carried a briefcase and later introduced himself as Jack, calmly explained that the other two were dating, but that they were going through a rough patch. He claimed he was helping them resolve their differences.

Henry and I hesitated as I wondered whether any of this was my business. What if Jack were telling the truth? Was I trying to be a hero? I started to feel foolish.

Then the woman bolted down the crowded sidewalk and into the street, oblivious to the rush-hour traffic. Henry and I chased after her. By the time we caught up to her, we decided we had to stay close until we could be sure she was safe.

Henry and I followed Jack and the woman at a distance, watching as the two of them made out, then walked across the street into a bar. Soon the boyfriend reappeared and the two men became aggressive towards us, insisting they didn’t need our help. The woman said we were starting to annoy her.

But every time I began to think that Henry and I were overreacting, she would bolt again, sometimes into moving traffic. As bystanders, what role did we have in preventing what I worried could potentially become a sexual assault or a car accident? When should we walk away?

“There’s no one answer to any of these questions,” says Emily Rosser, who runs a bystander intervention program at the University of Windsor. Adapted from a course pioneered by the University of New Hampshire, Bringing in the Bystander is a three-hour-long workshop that’s being incorporated into first-year undergraduate courses at the University of Windsor. Facilitators train participants to identify potential acts of sexual violence, and suggest direct and indirect ways they can prevent them.

A large portion of that training focuses on helping participants overcome their initial reluctance to become involved. That reluctance, known in social psychology research as the bystander effect, is heightened in large group settings—in my case, the busy streets of downtown Toronto—when individuals assure themselves that someone in a position of authority will eventually intervene.

And there are other barriers. “Society tells you interpersonal relationships and sexuality are private, and we don’t get in other people’s business,” says Rosser. “So if you hear someone beating up their wife . . . in the apartment across the hall, how long do you hear it before you knock on their door or call the police?”

Throughout the evening, as Henry and I mulled over what to do next, my mind kept returning to a viral Facebook post I’d seen earlier in the summer. According to the post, three women were having drinks at a restaurant one evening when one of them spotted a man at nearby table slip something into his date’s drink while she was in the bathroom. The three women reported him to the restaurant staff. When the man’s actions were confirmed on security footage, the staff called the police. As the Facebook post was shared and reshared, the women were hailed as heroes.

But that post as I remembered it described a more straightforward incident than the one I was facing: the man had clearly been engaging in suspicious activity, and the staff were able to take action. In our case, Henry and I couldn’t think of anyone to call for help aside from the police, yet dialing 911 seemed extreme.

To Rosser, calling the police is not the obvious solution. “That’s actually not an option for someone who’s been overpoliced, particularly black students, or people who are recent immigrants,” she says. “There are a lot of people who are afraid of any kind of involvement with law enforcement, or even campus security.”

When police do get involved, she says, they often take limited action. She refers to the Globe and Mail’s recent Unfounded investigation, which brought to the fore the alarmingly high rate of sexual assault cases that Canadian law enforcement dismissed due to insufficient evidence, as an example. “So while we work on fixing that institutionalized situation, we also have to think about, realistically, what else can we do?”

As part of its curriculum, Bringing in the Bystander holds discussions about real scenarios, often ones that participants are already familiar with. These include the Stanford rape case of 2015, when two graduate students chased down Brock Turner, whom they’d seen sexually assaulting an intoxicated woman in an alleyway. The students held down Turner and called the police. When the news broke, they, too, became media heroes and role models.

“The Brock Turner sexual assault case proves that bystander intervention works,” a Business Insider headline declared. But the two graduate students were lucky: although they were visibly shaken, they weren’t physically harmed.

“What tends to be taken up in the media . . . is that story of the hero, and direct intervention, and a highly risky intervention, because we like that story,” says Rosser. “But that’s not the majority of situations we’re trying to teach students.” There are other, more subtle ways to intervene, she says: if something looks suspicious at a party, for instance, flicking on the lights or turning off the music can be a quick way to diffuse uncomfortable situations. If someone is being harassed in a public place, strangers can walk up to the victim and pretend to know them, gently pulling them away from the line of attack. But quiet interventions rarely make the news.

“It’s a lot harder to find a good example that valorizes that behind-the-scenes interruption,” says Rosser. “The kinds of interventions we want to encourage are not that heroic in terms of our social scripts about heroes.”

The Stanford intervention could have turned out far differently. In Vancouver last June, three men aboard the Skytrain threatened a female passenger, saying they’d follow her home, then joked about raping her. When a bystander told them to leave her alone, they attacked him, punching him in the face and upper body before running away.

Last November, Isidro Zarate spotted a man beating a woman in a Walmart parking lot in Texas. When he approached them and told the man to let her go, the assailant pulled out his gun and fatally shot Zarate.

And this past May, when a poet, a recent college graduate, and a U.S. veteran and father of four stepped in to defend two young girls from verbal abuse on a train in Portland, Oregon, two of them were stabbed to death.

Such incidents serve as a reminder that our initial hesitations to intervene aren’t wholly unfounded. “You’ve got to look at your own vulnerabilities as well,” says Rosser. “You’re not God. I think it’s very important to accept our limitations in the moment.”

When we ran out of options, I called the police. While we waited, Henry and I chatted with the staff outside the bar where Jack had taken the young woman. They told us the two of them had been there earlier in the evening and were asked to leave after having disturbed the other patrons. Though the staff was friendly, they couldn’t help us—possibly because it was a busy Wednesday evening, wine was selling at half-price, and an intervention might dampen the mood.

About a half hour after the call, two officers arrived. They questioned the boyfriend while Jack watched from a short distance. We eventually approached one of the officers. Had we done the right thing? We asked. The officer shrugged wearily. People see something wrong, they can always call the police, he said. The two men weren’t going to face any consequences, aside from a bit of public humiliation. I don’t know what happened to the young woman.

Two men exited the bar and told Henry and me they’d been watching the scene unfold. They called us “Good Samaritans,” somewhat mockingly, and made it clear that if they had been in our place, they would have walked away.

Last September, the government of Ontario announced it was rolling out a $1.7-million program to train bar staff and management to recognize and act on signs of sexual harassment. I wonder now if such training would have changed the bar staff’s attitude. In the past year, bars have increasingly offered variations on an “angel shot,” a code name for a drink that patrons can order to signal to staff that they need help getting out of an uncomfortable situation.

But though nearly half of sexual assault cases involve alcohol, bar staff shouldn’t be the only ones charged with preventing violence. If the right training were more widely offered, participants could learn to not only intervene in acts of overt physical or verbal assault, but to recognize everyday language and actions that are symptomatic of a larger problem: the attitude that intoxicated women are easy, willing targets of sexual advances.

After talking to the officer, Henry and I agreed there wasn’t much more we could do and decided to go home. Even though we were still basically strangers, we shared an Uber. Jack and his friend were acting openly hostile toward us, despite the police officers’ presence. Neither of us wanted to walk alone. If we were to get into trouble, I, for one, wasn’t confident that any bystanders would help us.