In August 2009, Scott Conarroe set out from Toronto in his 1992 Toyota to photograph the North American coastline, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from the Gulf of Mexico all the way up to Alaska. After nearly a year on the road—travelling alone, with a few clothes, an atlas, a foam mattress, and his Wista RF field camera—he returned home. In March 2011, he debuted By Sea, an exhibit of his journey, at the Stephen Bulger Gallery in Toronto. Soon afterward, he completed the ambitious project at last, documenting the Arctic with the Canadian Forces Artists Program.

Conarroe, thirty-eight, cites Impressionism as an early influence, along with beat generation photographer Robert Frank. In the ’50s, Frank toured the United States in a used Ford coupe, recording the land and its people for his seminal book, The Americans. “All of that beat scooting around seems germane to my experience,” says Conarroe. “The Americans was a cherished visual memento of that scene, and about something other than the artist. I gravitated right to it.”

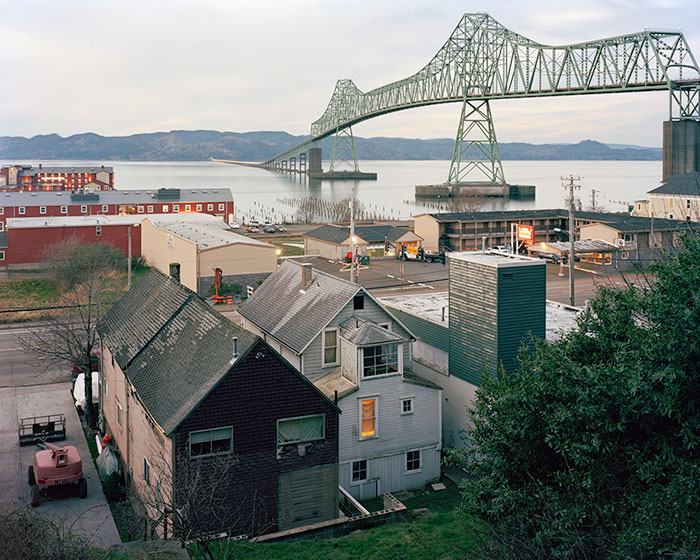

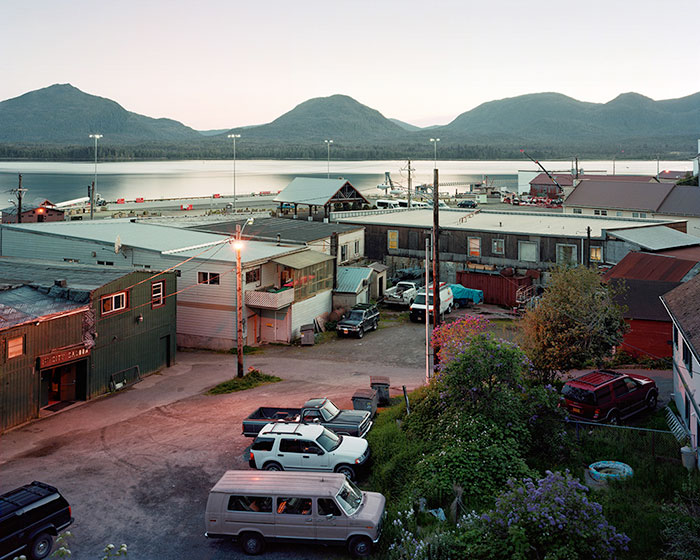

Now at work on a project about China’s landscape and railways, Conarroe expresses his aesthetic through routine and technique. He wakes before sunrise, shoots at dawn and dusk (“when the light is dreamy and pretty”), and employs prolonged exposures. “When I open the shutter, the sky is one colour,” he explains. “By the time I’m done, it’s a little brighter or darker, going from pink to blue, orange to grey. In a way, the aesthetic is an idealized look at things. But the camera records all sorts of details. It makes frank descriptions.”

As well as evoking the beauty of the continent’s periphery, the surreal, indelible images in By Sea preserve a fleeting impression. Taken together, they remind us of the coastline’s fragility and its ever-shifting nature. “I often imagine that we’re looking back at this moment nostalgically,” Conarroe says, “right before we accepted that the climate was changing and sea levels were rising. The pictures capture a precarious point between a golden age and whatever is about to happen.”

—Introduction and additional text by Julien Russell Brunet

Scott Conarroe on beginning: “I didn’t go to art school right out of high school. I took a few years to loaf around, and become useless for most things other than art school. I lived in a van and drove around. I would work in the bush in the summer and go skiing in the winter. So, these types of projects are a reasonable match for the skills I had before I found photography.”

On Impressionism: “You get to see the work and you get to see the image and you get to see the ambience. Each [element] carries its own weight, but they all function together and complement one another.”

On the coast: “The coast is such a perfect subject. So much happens there. It’s the place where this civilization that we are part of began. And now we’re being followed up over the shore—rising sea levels are a real and important part of our present and future. As a metaphor, it’s also the classic example: it’s a perfect division of us and the unknown.”

For his first major project, By Rail, Conarroe toured North America in a 1981 Chevy that ran on propane. He replaced it with his ’92 Toyota—“a much subtler van”—before starting By Sea. (“These projects kill old cars,” he laughs.) The Chevy is now parked, semi-permanently, at a wine farm in Cawston, BC, as a sort of micro-apartment for fruit pickers.

In his introduction to Frank’s The Americans, Jack Kerouac wrote of “madroad driving men ahead” and of “the humor, the sadness, the EVERYTHING-ness and American-ness of these pictures.“ The same phrases describe Conarroe’s trip and his images, but with one important caveat: this work is distinctively North American.

On shooting: “I like looking at how different things are organized around one another rather than looking at things [by] themselves. I’m happy with established pictorial conventions that most viewers can comprehend and enter into without much fuss.”

On the road: “There are moments when it’s from hand to mouth and there are moments when it’s feasting. That’s also why I do these big, long projects. Sometimes, it’s easier to float around making pictures and be homeless than it is to actually maintain an apartment in any neighbourhood I’d like to live in. It’s romantic and awesome, and it’s also because I’m super cheap and often broke, so I’ll go camping for the summer instead of paying rent.”

Conarroe’s travel advice: (1) Best places to park overnight: “Near where I’m shooting in the morning, the beach, hotels with open internet. Level, quiet, and dark is comfortable.” (2) Essential supplies: a cooler that plugs into the van’s cigarette lighter, sunglasses, water. (3) Road diet: “Lots of fruit and olives, granola, hummus, bread. I make a point of checking out breakfast specials along the way.”

On his favourite shot in the project: “It’s funny and sad and gorgeous. It describes two distinct realities abutting one another with a very basic and yet somehow immense visual vocabulary.”

This appeared in the January/February 2013 issue.