Here’s a thought experiment. At some point during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a Russian commander gives the order to shoot down two Ukrainian fighter jets. One set of missiles hits its target, but the second accidentally blows up an American spy plane, killing dozens of crew members.

When video of the crash site emerges, Western capitals fill with demonstrations. Misreading the outrage as the opening stages of a military response by NATO countries, Russia decides to strike first, as a deterrent. It targets early warning systems, knocking out satellites and unleashing a cyberattack. In the spreading confusion, as the president of the United States decides to wait for more information, Russia’s leader becomes convinced that enemy missiles are about to rain down on his country and launches nuclear warheads. Tens of millions die, with more succumbing to radiation over the following days and weeks.

The above scenario comes from the Nuclear Threat Initiative, a Washington-based think tank dedicated to global security. As the fighting in Ukraine grinds on and Russia contends with military setbacks and a domestic economy hammered by sanctions, NTI’s president, Joan Rohlfing, has deemed the threat of nuclear war to be at its highest since the Cuban Missile Crisis, almost sixty years ago. She isn’t alone. In recent months, experts have scripted other ways a tit-for-tat escalation might bring about the end of civilization: so-called malign actors—or hackers—interfering with communications systems; Russian president Vladimir Putin testing European resolve by seizing Polish territory; a frustrated Russian leader using tactical nukes (smaller, short-range arms capable of great devastation) to shock Ukraine into surrendering; or just a plain old-fashioned error that triggers an inadvertent missile launch.

Putin has demonstrated a readiness to think the unthinkable. He already put his nuclear arsenal on high alert at the start of the invasion, and in comments made to Russian state media in late March, Dmitry Medvedev, deputy chairman of Russia’s security council, offered little reassurance. Mirroring the US’s own first-use policy—in which officials assert the right to initiate a nuclear conflict—Medvedev explained that Russia’s nuclear doctrine doesn’t require an adversary to act first. Instead, he said, Russia will resort to extreme measures in situations that “jeopardized the existence of the country itself.” And it can recognize that threat however it wants.

Russia’s nuclear sabre-rattling isn’t new. In 2008, it threatened Poland when the country agreed to host a US missile-defence base. In 2015, Russia warned that it was ready to use nuclear weapons to defend its annexation of Crimea. And, soon afterward, it menaced Danish warships when Denmark joined NATO’s missile-defence system. But, in April, when Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov raised the possibility of a third world war over how NATO has stepped up the supply of weapons to Ukraine—the risk of a nuclear conflict, Lavrov said, “should not be underestimated”—Russia exposed the extremism of its brinkmanship. During a recent video speech at an international conference, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy said, “Russia is deliberately bragging they can destroy with nuclear weapons not only a certain country but the entire planet.”

Paul Meyer is a former Canadian diplomat who served as ambassador on disarmament to the United Nations. Today, he directs the Canadian Pugwash Group, the national affiliate of a global disarmament organization that won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1995. He believes the crisis in Ukraine has exposed a failure of global governance. Over the last decade, Russia has made a renewed point of investing in military capabilities, funded by the boom in fuel exports. But it’s not just Russia that has moved its nuclear chess pieces into offensive positions. Of the sixteen missile tests North Korea has conducted so far this year, one was capable of delivering a nuclear warhead. China has expanded its arsenal. India and Pakistan became nuclear powers by the late ’90s, and their relationship remains largely hostile. And the US—the only country to ever drop a nuclear bomb in combat—announced a $1.2 trillion (US) investment in new nukes during Donald Trump’s presidency. Not only does the Ukraine crisis strengthen the argument for taking steps to eliminate these weapons, says Meyer, but world leaders must embrace nuclear-weapons control. “Disarmament diplomacy,” he says, referring to the leading role Canada once played, “was a whole ecosystem. But it’s now largely gone.”

That diplomacy, in the form of arms-control agreements, helped decrease the number of nuclear weapons in the world. According to the Federation of American Scientists, we have gone from an estimated 70,300 warheads in 1986 to about 12,700 today. (The vast majority are likely held by the US and Russia.) Canada was once a linchpin in that effort within NATO and the UN, and it remains a global exemplar as one of the few countries—along with Ukraine, ironically—to give up its nuclear arms. Justin Trudeau has said little about the sudden reemergence of aggressive nuclear intimidation tactics over Ukraine, but Meyer believes the prime minister could play a vital role in leading the disarmament cause. And, if he did, he would have an excellent example to follow: his father.

As prime minister, Pierre Trudeau was far from a pacifist. He didn’t hesitate to use the War Measures Act to mobilize the army against terrorism in Quebec in 1970. In 1980, he oversaw the purchase of a fleet of American fighter jets. Trudeau also allowed the US to test cruise missiles in Alberta in the 1980s despite fierce public opposition. But, when it came to nuclear weapons, he passionately supported disarmament. “He was very consistent about it,” recalls Thomas Axworthy, who served as Trudeau’s principal secretary and speechwriter. “If you’re a supreme logician, as he was, you can’t help but oppose weapons that can destroy the world.”

At the time, the prospect of nuclear annihilation was hard to ignore. Starting in the late 1940s, the US and the Soviet Union began stockpiling missiles feverishly while trusting in the logic of mutually assured destruction (MAD). Each country believed its enemy would be deterred from initiating an attack because both sides knew that pressing the button would be suicide. For Trudeau, MAD inched the world closer to doomsday. Speaking at the United Nations in 1978, he suggested “a strategy of suffocation” that would deprive “the arms race of the oxygen on which it feeds.” His proposal included a ban on weapon-system testing, a prohibition on materials for nuclear weapons, and reduced spending on new weapon systems. Meyer describes Trudeau’s speech as setting “the blueprint for Canadian disarmament diplomacy for years.”

By the early 1980s, however, arms-reduction efforts began facing headwinds. Ronald Reagan was sharpening his rhetorical attacks on the Soviet Union as an “evil empire” while the US spent billions pursuing a space-based shield against missile attacks. Dubbed “Star Wars,” the proposed defence system threatened to undermine MAD by suggesting that a nuclear war could be won. Alarmed at the volatile state of the arms race, Trudeau mounted a peace initiative. Between 1983 and 1984, he travelled around the world, visiting seventeen countries and meeting with over fifty government leaders, including in the US, the UK, and the Soviet Union. Although Trudeau believed military force was needed in some circumstances, says Axworthy, “he wanted détente, and he wanted to try to reach an understanding with the Soviets.” Even after the USSR’s crackdown in Czechoslovakia, in 1968, and its invasion of Afghanistan, in 1979, Trudeau pushed for diplomacy, largely because of tensions between NATO and the Soviets over duelling missile deployments. “At heart,” says historian John English, who wrote a two-volume biography of the former prime minister, “Trudeau truly thought that the best thing Canada could do for the world at the time was to try to get the dialogue about nuclear disarmament back on track.”

America’s cold warriors were unimpressed. Lawrence Eagleburger, then US under secretary of state for political affairs, reportedly described Trudeau’s peace initiative as “akin to pot-induced behavior by an erratic leftist.” The response in Canada—particularly from the military and the Progressive Conservative Party—was also skeptical, recalls journalist Geoffrey Stevens, who followed Trudeau’s nuclear-disarmament efforts throughout the 1970s and early ’80s. “A lot of people thought it was lame at the time,” says Stevens.

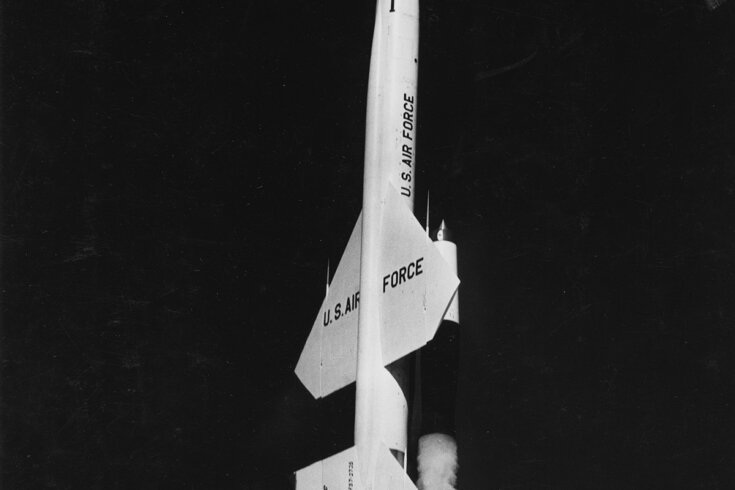

But Trudeau also led by example. When he took office as prime minister in 1968, recalls Axworthy, Canada played several hefty nuclear-weapons roles within NATO, most importantly by providing squadrons trained to fly nuclear warheads and a base in North Bay, Ontario, for US-made Bomarc missiles. By the time he left office, in 1984, Canada had no nuclear-weapons roles—an accomplishment that was noted when he won the Albert Einstein Peace Prize that year. Trudeau joined a group of former world leaders called the InterAction Council, co-founded in the early 1980s by his friend Helmut Schmidt, former chancellor of West Germany. The IAC was active on nuclear issues and arms control, and Trudeau played a role on the council right up until he died, in 2000.

Trudeau’s diplomacy had dramatic results. “I worked with Mikhail Gorbachev at one point, and I asked him about Trudeau’s impact on the nuclear arms race,” says Douglas Roche, a former senator who served as the Canadian ambassador for disarmament in the 1980s. “Gorbachev told me Trudeau’s work for nuclear disarmament contributed significantly to an improved international atmosphere and thus better relations between the US and the Soviet Union.” This was the atmosphere that brought Gorbachev together with Reagan in Reykjavik and led to the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. The INF, signed in 1987, was one of the most consequential treaties in history and the first to abolish an entire category of nuclear weapons.

If Justin Trudeau, who took office in 2015, has a vision for a world without nuclear weapons, he hasn’t shared it. In some ways, he has kept in step with an unspoken national policy. Disarmament diplomacy, Meyer explains, “continued through the Mulroney and Chrétien years, but since then, there’s been a general retreat and decline.” The drop-off, says Meyer, started when Stephen Harper assumed power, in 2006. “There was almost an indifference to it,” he says about arms control. Thanks in part to the Harper government’s vigorous support for mining, Canada is today one of the world’s largest producers of uranium, an ingredient essential for making certain nukes. A 2021 report from Pax, a Netherlands-based peace group, spotlights numerous Canadian banks and insurers for their large investments in scores of companies involved in producing nuclear weapons.

Canada is not in the club of nuclear-armed states, which, along with Russia and the US, includes the UK, China, France, India, North Korea, and Pakistan. But, alongside its pro-uranium stance and quiet reversal of Trudeau père’s disarmament legacy, Canada is currently identified as a “nuclear weapon endorser” by the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, a disarmament lobby founded in 2007. Partnering with hundreds of peace, rights, and development groups from across the world, ICAN is a coalition working to counter the idea that the nuclear threat has receded, an assumption that has coincided with the modernization of arsenals and a dismantling of arms-control frameworks. In 2017, the same year it won the Nobel Peace Prize, ICAN convened conferences at the UN to adopt the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which aims to make nukes illegal in the same way chemical and biological weapons are. So far, of the eighty-six nations that have signed the TPNW, sixty-one have ratified or acceded to it. Canada, however, stands with the nuclear powers in opposing the treaty for failing to take into account the security concerns that underpin the belief in nuclear deterrence. The Trudeau government voted against a 2017 parliamentary motion urging the treaty’s adoption.

“The Canadian government’s reaction to the TPNW can be characterized as one of dismissal, deflection, and denial,” wrote Meyer in 2021. Much of that reaction appears to centre on a disagreement about the ban treaty’s efficacy. Specifically, Canada believes the treaty, while laudable, is a waste of resources—without the nuclear club’s support, the TPNW has no teeth. Of course, this didn’t stop the Trump administration from pressuring states that ratified the treaty into repudiating it, calling their decision “a strategic error.” Canada, Meyer explains, would rather focus its disarmament efforts on what Justin Trudeau called “concrete measures” and espouses the more traditional, incremental, “step-by-step” approach. This despite the fact that many of the identified steps—such as the proposed Fissile Material Cut-Off Treaty, created to halt the production of central ingredients used in nuclear weapons—have languished for decades.

If Canada truly believes in existing treaty processes, says Meyer, it should demand that the nuclear club commit to implementing them. It should also break ranks and back the TPNW process, thereby making it harder for countries like the US to pretend the status quo is tenable. Seven former Canadian prime ministers, foreign ministers, and defence ministers—among them Jean Chrétien and John Turner—signed an open letter, released in September 2020, calling for “courage and boldness” in joining the treaty. The TPNW is also in step with national sentiments.

Last April, a Nanos survey showed that 80 percent of Canadians want the world to eliminate nuclear weapons. That work could start with Trudeau pushing for a new détente between the West, Russia, and China to slow the newly feverish arms race. On the prospect of Trudeau deciding to do so, however, Meyer is dubious. “I’m not a psychologist,” he muses, “but, let’s face it, lots of guys resist doing exactly what their fathers did.”