In the summer of 1995, Maria Sebregondi was mulling over a knotty question, sailing with friends off the Tunisian coast. At thirty-six, she had already enjoyed a fruitful career, translating Marguerite Duras, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Vladimir Nabokov into Italian. She was particularly intrigued by the French pair of Georges Perec and Raymond Queneau, who wrote novels and poetry using formal constraints as a spur to creativity. Perec had written an entire novel, La disparition, without using the letter “e”; in Exercices de style, Queneau told the same simple story in ninety-nine versions, using a different prose form for each one. They called their playful genre Oulipo, an acronym derived from the French for “workshop of potential literature.” So Sebregondi was accustomed to the generation of ideas within set parameters, and on this particular sultry evening, she was presented with just such a challenge.

Her holidaying shipmates included Francesco Franceschi, a friend whose company Modo & Modo sold designer gifts, and that night, he shared a problem. His business depended on other people conceiving and manufacturing products for him to sell, which kept profit margins low. What, asked Franceschi, could Modo & Modo manufacture themselves and thus sell more profitably? The group exchanged ideas long into the night, discussing emerging trends like cellphones, email, and cheap flights. They decided that the consumer they wanted to target with a hypothetical new product belonged to this new era: creative, free spirited, and mobile. Sebregondi labelled their design-conscious customer the “contemporary nomad.” But before any of the party could work out what to manufacture for them, the holiday was over and she had returned home with her children to Rome.

The question nagged at her for weeks, and she toyed with ideas, including a traveller’s toolkit containing exquisitely designed pens, bags, T-shirts, penknives, and so on. Nothing met the requirements of Franceschi’s brief, which demanded a product that would be easy to produce yet offer wide commercial potential. Then she came across two passages in the book she was reading for pleasure: The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin, a global bestseller since its publication eight years before. In the novel, a lightly fictionalized version of Chatwin explores the Australian outback, coming to understand that its aboriginal culture offers an insight into the origins of human culture—and perhaps into the restlessness of human nature itself. Conspicuously “creative, free spirited, and mobile,” Chatwin himself seemed a perfect fit for the “contemporary nomad,” and two passages in his novel triggered Sebregondi’s memory:

“Do you mind if I use my notebook?” I asked.

“Go ahead.”

I pulled from my pocket a black, oilcloth-covered notebook, its pages held in place with an elastic band.

“Nice notebook,” he said.

“I used to get them in Paris,” I said. But now they don’t make them any more.”

“Paris?” he repeated, raising an eyebrow as if he’d never heard anything so pretentious.

Then he winked and went on talking.

Later in the book, Chatwin expands on the story.

Some months before I left for Australia, the owner of the papeterie said that the vrai moleskine was getting harder and harder to get. There was one supplier: a small family business in Tours. They were very slow in answering letters.

“I’d like to order a hundred,” I said to Madame. “A hundred will last me a lifetime.”

She promised to telephone Tours at once, that afternoon.

At lunchtime, I had a sobering experience. The headwaiter of Brasserie Lipp no longer recognised me. “Non, Monsieur, il n’y a pas de place.” At five, I kept my appointment with Madame. The manufacturer had died. His heirs had sold the business. She removed her spectacles and, almost with an air of mourning, said, “Le vrai moleskine n’est plus.”

This passage had struck many of Chatwin’s readers; its intimations of mortality seemed to foreshadow the author’s premature death only a year and a half after the publication of The Songlines. But to Sebregondi, it meant something more personal, because she recognized, from her time as a student in Paris, the notebooks Chatwin described. Indeed, she still had several. Digging them out of old boxes, she looked at them for the first time in years—and with new eyes. Why had Chatwin become so attached to this particular model that he would order a hundred rather than risk running out? How could such a utilitarian object assume such importance? Then it struck her that she might have hit upon a solution to Franceschi’s challenge—a simple product, easy to manufacture, appealing to creatives and imparting promises of travel, of glamour, of discovery.

Phone calls to France confirmed Chatwin’s account (a sensible move: Chatwin always preferred a good story to the literal truth), and Sebregondi’s hunch was confirmed by serendipitous sightings of le vrai moleskine in other contexts: exhibitions of Matisse’s and Picasso’s sketchbooks, a photo of Hemingway at work. This product, she realized, already had a pedigree. More to the point, it had commercial promise, for millions around the world had already read Chatwin’s endorsement. It even accorded with the classic principles of Italian design: like an espresso, a pair of Persol sunglasses, or a Prada dress, le moleskine was minimal, functional, and assertively black.

And yet, miraculously, no one made it anymore.

Sebregondi took the idea to Milan, where Franceschi realized that she was on to something. With Chatwin having already solved the thorniest problem faced by anyone marketing a new product (what to call the damn thing), the pair entered what became a two-year process of product design, which resulted in the classic Moleskine notebook.

You don’t need me to tell you what a Moleskine looks like, but you may not have considered how insistently its design sends messages to the contemporary nomad. The minimal black cover looks, at first glance, like it might be leather: robust but also luxurious. The non-standard dimensions, a couple of centimetres narrower than the familiar A5, let you slip the notebook into a jacket pocket, and the rounded corners—which add considerably to the production cost—help with this. They also stop your pages from getting dog-eared and, together with the elastic strap and unusually heavy cover boards, confirm that the notebook is ready for travel. The edges of the board sit flush with the page block, ensuring that your Moleskine can never be mistaken for a printed book. In use, it lies obediently open and flat, and the pocket glued into the back cover board invites you to hide souvenirs—photos, tickets stubs, the phone numbers of beautiful strangers. Two hundred pages suggest that you have plenty to write about; the paper itself, tinted to a classy ivory shade and unusually smooth to the touch, implies that your ideas deserve nothing but the best, and the ribbon marker helps you navigate your musings. Discreetly minimal it may seem, but the whole package is as shot through with brand messaging as anything labelled Nike, Mercedes, or Apple—and, like the best cues, the messaging works on a subconscious level.

But in case those cues alone were not enough, Moleskine spelled out its brand values in the small folded leaflet which the notebook’s new owner would “discover”—as Sebregondi tellingly puts it—tucked in the pocket. The leaflet’s copy has evolved over time, and more and more languages have been added to it, but the central message has changed little from the early, Italian-only, version:

The Moleskine is an exact reproduction of the legendary notebook of Chatwin, Hemingway, Matisse. Anonymous custodian of an extraordinary tradition, the Moleskine is a distillation of function and an accumulator of emotions that releases its charge over time. From the original notebook a family of essential and trusted pocket books was born. Hard cover covered in moleskine, elastic closure, thread binding. Internal bellowed pocket in cardboard and canvas. Removable leaflet with the history of Moleskine. Format 9 x 14 cm.

The leaflet opened with a lie (the new Moleskines were not “exact reproductions of the old”) then immediately veered toward gibberish, but that didn’t matter. Pound for pound, those seventy-five words proved themselves among the most effective pieces of commercial copywriting of all time, briskly connecting the product’s intangible qualities—usefulness and emotion—to its material specification, thereby selling both the sizzle and the steak. Sebregondi and Franceschi picked an astutely international selection of names to drop: an Englishman, an American, and a Frenchman encouraged cosmopolitan aspirations. “Made in China,” on the other hand, did not, so they left that bit out.

Modo & Modo ordered the initial production run of 3,000 notebooks in 1997, and the new Moleskine first went on sale in Milan, in a small bookshop on the Corso Buenos Aires. It sold through its consignment in days. Avoiding traditional stationers, the company targeted design retailers and bookstores: the strategy worked, and in 1998, they sold 30,000 notebooks. From 1999, they used their existing networks to distribute around Europe and then across the Atlantic. Within ten years, the American chain bookseller Barnes & Noble had become the brand’s largest retail partner. Just as Franceschi had hoped, the high profit margins transformed Modo & Modo’s fortunes. In 2006, a private equity firm bought him out, and sales continued to grow.

In 2013, the Moleskine SpA launched on the Italian stock exchange, and in 2016, a Belgian car distributor bought the company outright, for half a billion euros. Small wonder that the story is now taught in business schools as a textbook example of successful product design and marketing. In 2017, the story came full circle when Moleskine and Chatwin’s publisher struck a deal to publish a new edition of The Songlines, bound in the now-familiar black boards, complete with elastic closure, rounded corners, ribbon markers, and pocket. You bought it shrink-wrapped to a blank journal, embossed—in a gesture which Chatwin would surely have recoiled from—with the motivational boost “Enjoy your travel writing.”

Sebregondi herself stayed relentlessly on message for two decades, giving scores of interviews whose recurring theme was that the Moleskine was “first of all, an enabler for creativity.”

Having stayed with the business through its various incarnations, she stepped back in 2017 and currently gives her time to the charitable Moleskine Foundation, which aims to drive social change, especially in sub-Saharan Africa and Eastern Europe, through—naturally—creativity. She also remains involved with Oplepo, the Italian offshoot of Oulipo. Her most recent translation is of Queneau’s One Hundred Thousand Billion Poems, in which the reader randomly generates sonnets from the book’s thousands of rhyming lines, constraints proving creative.

I bought my first Moleskine during the early years of that boom and, a while later, found myself working for a book publisher keen to share in the Moleskine-driven growth of the upscale stationery market. Notebooks, we reasoned, had no words and no pictures—the tricky, expensive things that make “real” books so difficult to profit from. How hard could it be to cash in? So we created a range of notebooks, brightly designed and packed with gimmicks, and placed a substantial order at the printers. I was charged with visiting Barnes & Noble’s Fifth Avenue head office to present our wares, and I suggested that our colourful product could supply healthy turnover if racked alongside Moleskine in their stores.

The buyer eyed me skeptically. “Along with the Moleskines,” he said. “Do you know there’s a section of our customer base that buys a fresh Moleskine every time they come into a store? Once a week, some people. We have no idea what they do with them.”

I showed off my samples, stressing the cream paper, the ribbon markers, and the striking cover designs that supposedly set our brand apart. He shook his head and handed me a familiar black notebook in response. “See this?” he said. “We make them ourselves, own brand. The same size, the same number of pages. We use the same paper, the same boards, we make them at the same plants in China. They’re every bit as good as a Moleskine, and we ask half as much for them.” He paused for effect. “And Moleskine still outsells us. And you’re asking me to take shelf space away?”

I was learning a hard lesson about the power of the brand. Others, however, made a better go of it. From 2005, Leuchtturm, whose specialty had been stamp collectors’ albums, took on Moleskine, matching them for quality while offering—the vulgarity!—a range of colours; older companies like Clairefontaine, Rhodia, and Paperblanks refreshed their offerings. Western hipsters, always alert to high-end Japanese design, started to import notebooks from companies like Midori, Hobonichi, and Stalogy, which bested any of the European brands with their exquisite papers and bindings (Moleskine and Leuchtturm both use mainly Taiwanese paper). In the US, Field Notes struck a utilitarian chord with a mid-century aesthetic. All presented a fresh spin on the basic product, and all benefited from the product building that Moleskine had done. If you cared for upmarket stationery, the 2010s were a golden age.

At the same time, the Moleskine became a potent status symbol. Tech CEOs toted them, as did the designers, journalists, and writers whom Sebregondi had envisaged—and even more people whose aspirations perhaps outran their actual creativity. Spotted in your local Starbucks, these characters were easily mocked: the satirical website Stuff White People Like made hay with their accessorizing, as did the right-wing politician Karl Rove, who once told his audience at Yale that he knew them to be pretentious by their Moleskines. The mockery did nothing to hurt sales.

Neither did a growing interest, from psychologists and lifestyle gurus, in the notebook’s practical effectiveness. Sebregondi herself suggested that the notebook’s minimal form made it a perfect creative tool, talking of it in the same terms as Queneau’s deliberately constrained work: “a simple object,” giving her the “sense of extraordinary possibility born from small things.” The productivity guru David Allen recommended making lists in notebooks, as did neuroscientist Daniel Levitin; the journalist David Sax wrote a book, The Revenge of Analog, which depicted paper notebooks (along with vinyl LPs, board games, and film cameras) mounting a spirited resistance against digital replacement. It became commonplace to contrast the old technology with the new. The original Moleskine had launched at the same time as the Palm Pilot, the first hand-held digital organizer, and had, from day one, faced competition from increasingly powerful devices. The laptop, the BlackBerry, the iPhone, and the iPad all seemed to offer far greater functionality than their paper antecedent, but a stubborn constituency of users refused to move over into the digital sphere, and numerous peer-reviewed studies soon showed that their obduracy made sense. Something about the act of writing by hand, and the production of a physical object, makes the older technology more effective than the new. Sebregondi had, unwittingly, prompted serious inquiry into the workings of the human brain.

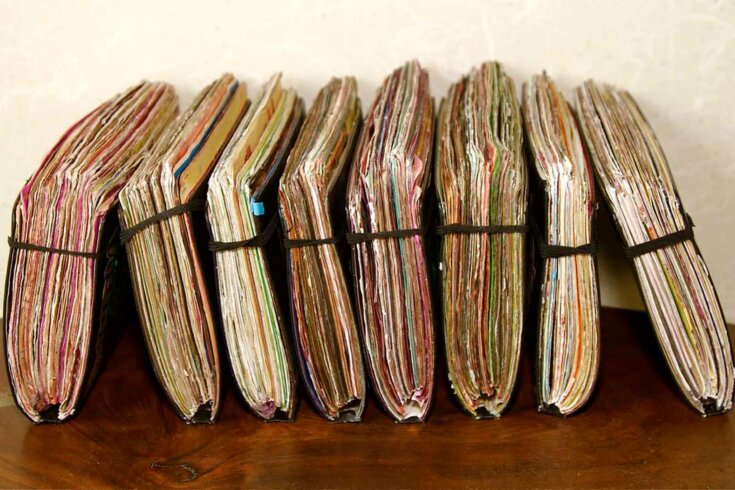

My own interest in notebooks had also progressed beyond the commercial. I read Samuel Pepys, loving the unfettered way in which he documented work, home, leisure, his urban environment, and his sex life; then I discovered my grandfather’s eye-opening pre-war diaries, just as wide ranging, although much briefer. So I started keeping my own journal in 2002, and each year added to a steadily growing heap of battered notebooks.

Writing a diary made me happier; keeping things-to-do lists made me more reliable (which, in turn, made those around me happier), and I learned never to go to a doctor’s appointment, or a meeting of any kind, without taking notes of what I heard. But there appeared to be creative benefits too. Every artist I met seemed to have a sketchbook to hand, as did graphic designers—and even web designers, whose product was entirely digital. Authors all kept notebooks, as did journalists, critics, and other creative types—and the more assiduously they used those notebooks, the better their work seemed to be. The same applied to my colleagues’ work: playful lists, diagrams, and sketches regularly disgorged surprisingly good ideas.

When notebooks appear on the scene, interesting things happen. To open up to the blank page and interact with it takes energy and sometimes a little courage.

But the rewards may surprise.

Excerpted from The Notebook: A History of Thinking on Paper by Roland Allen. Copyright © Roland Allen 2024. Excerpted with permission from Biblioasis. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.