There’s a misleading nugget about book sales that’s gone viral twice in the past fifteen months: the notion that, of all the trade titles published in a year, half sell fewer than a dozen copies. The statistic was originally floated in 2022, during the trial for the proposed (and later blocked) merger between Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster. Even as it surfaced, people queried the figure—Jane Friedman, who reports on the industry, noted that there was no source given during the relevant testimony—but the statistic was too juicy not to travel. Was the industry really that bad at doing business? Many implicated by the dirty dozen—largely writers but also publishers—alternately quaked and failed to hide their smugness.

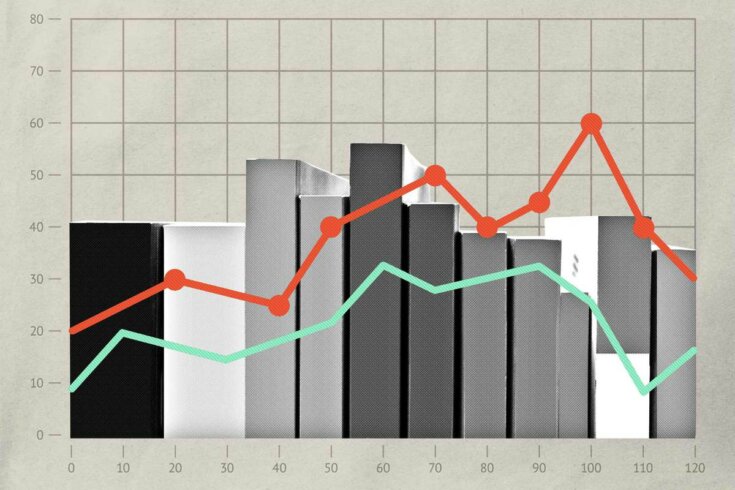

Others set about debunking it. Kristen McLean, an analyst at NPD BookScan, the industry-standard platform that tracks book sales in the United States, provided a more accurate data set in response to a newsletter by novelist Lincoln Michel, who was also rightly suspicious of the stat. McLean’s figures suggested that, of the new books published in the preceding calendar year, about 15 percent sold under twelve copies; 51.4 percent of books, meanwhile, sold between a dozen and 999 units. Neither of those figures is as alarming as the original claim. But nor are they especially encouraging. Sales are indeed down. According to an early-October report in Publishers Weekly, the first nine months of 2023 saw print book sales drop 4.1 percent compared to the same period in 2022. Reports from the preceding weeks had the Eeyore-ish titles “Print Book Sales Fell Again Last Week” and “Print Book Sales Improved Last Week, but Still Fell 4%.” In Canada, the drop is more pronounced: BookNet reported in August that print sales for the English-language trade market were down 12 percent in the first half of 2023 as compared to the same six months the previous year.

These figures are as high as they are in the first place only because of big tent-pole titles like Prince Harry’s Spare, which sold 1.1 million copies in the US in the year’s first quarter, or Suzanne Collins’s Hunger Games series (boosted by the franchise’s recent film adaptation), which helped push American Thanksgiving week sales higher than they’d been the year prior. Few titles can be relied upon to reach those heights—according to McLean’s data set, in 2022, less than half a percent of books even cleared 100,000. But this is the financial model on which the publishing industry operates: a small number of titles generate sufficient profit to keep the lights on, offsetting the vast majority of the rest. The marquee projects get the flashier promotional campaigns, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy: the authors expected to attract the most attention and resources from consumers are given the most attention and resources by their publishers (which in turn helps them attract the most attention and resources from consumers). As a 2019 Publisher’s Weekly piece on the “top-heaviness” of the industry put it, “as [the bestselling] books get the lion’s share of the houses’ focus, other titles are left to find audiences on their own.”

So where does that leave the rest of the writers? When it comes to things that actually move the dial—what writers can do to make their books rise above that bottom 50 percent of sales—the answers are often frustratingly random and disproportionately dependent on luck or resources. In a snapshot of the past year’s bestseller list in the New York Times, Elisabeth Egan noted that merely “eight noncelebrity debut novelists made it onto the hardcover fiction list,” and five of those got a leg up from major national book clubs. Some people—including a number of right-wing authors—have even bought their way onto the bestseller lists, causing the New York Times to mark conspicuously bulk-ordered titles with a small dagger.

There’s the lightning strike of virality, which may result in a sales spike. TikTok has long been touted as a place to try and manufacture that kind of attention, but BookTok users—who have built a community that runs on genuine excitement for what they read—are known to balk at content that feels patently corporate or inauthentic. A runaway post on any platform usually isn’t manufactured anyway. In October, a reader tweeted a photo of an underlined passage from Lee Seong-bok’s Indeterminate Inflorescence, a collection of lectures on poetry translated by Anton Hur. The post was simple and admiring: “I can’t imagine being a writer and not reading this book.” It garnered nearly 6,000 likes, over 800,000 views, and a response from the publisher, an independent press called Sublunary Editions, which confessed, “This tweet has perhaps sold more books more quickly than any single review we’ve ever had.”

All of which highlights the two faces of the book-sale process: its ideal operation and its fundamental flaws. At best, this is the circuit working as it should: quality writing reaching an audience of admiring readers via word of mouth. The problem is that such magic, albeit there for anyone to grasp at, is difficult to replicate—and it doesn’t come from the traditional forms of publicity the industry is built on. The finicky labour of trying to bottle hype is largely offloaded onto writers through the cultivation of their social media presences or newsletter audiences or names in media publications. I was advised to sound off on big news stories and join charged social media conversations that were vaguely related to the subject of my essay collection, with the idea that positioning myself as an expert on tangential subjects would make people buy the book. This particular manoeuvre seemed far-fetched even when I knew less about publishing than I do now, and it felt close enough to ambulance chasing that I got too queasy to try.

The enigma of how to sell a book touches all corners of literary culture. It affects what kinds of titles publishers acquire and, at the other end of the pipeline, which titles readers see the most. If you’ve ever felt the uncanny sense that some shadowy agent wants you to know about a certain book, you’re probably right. The fate of a book depends on so many small but consequential decisions that accumulate to ensure it reaches your awareness: the time of year it comes out, the runway it has to get pre-publication endorsements, the way it gets positioned by the publisher. And then, once a book is released, it has to contend with all sorts of other obstacles: The Amazon algorithm. The decline of outlets offering arts coverage. The drop in book sales themselves. In response, our best defence is to read beyond the bestseller lists and the most-hyped titles and support our local independent bookstores. Every book that finds you is a minor miracle.