The most difficult aspect of photographing a writer is to make sure that the portrait is not only a likeness of the person but a reflection of the writer’s work. When I began the process of chronicling Canadian writers during the ten years that Brian O’Riordan and I traveled throughout the country with our bags of books to be signed and my trusty tape recorder in my pocket, I had not anticipated that the photographs I took would eventually be collected into Portraits of Canadian Writers (The Porcupine’s Quill, 2016).

Thirty years ago, I was fascinated by the people we met and their larger-than-life personalities. Most of them were authors I had studied at high school and university; yet it saddens me that at the time I took them for granted. I thought they would always be with us. I thought they would continue to produce the kind of writing I wanted to learn from as a writer. I find it strange, now, to see them in bronze effigies in parks. They were people who had devoted their lives to putting words on paper. That to me was the marvel of what they did. Their writing was larger than their personalities.

Even after the adventures of Meyer and O’Riordan played themselves out in two volumes of oft-quoted interviews, In Their Words (Anansi, 1985) and Lives and Works (Black Moss Press, 1991), I continued to photograph writers I encountered. As the Laytons and the Purdys passed from life into legend, I realized that our writers need to be recorded beyond what they put on the pages of their books, so that the words can have faces attached to them.

There are so many more new voices who I want to photograph. My desire to record the authors of Canadian literature will probably not stop with this book.

Margaret Atwood

I met Margaret Atwood in 1977 at an event for former University of Toronto writers-in-residence. She was very ill at the time with a bad case of the flu, and no one wanted to go near her. I did. I was editing the centennial edition of the college’s magazine, Acta Victoriana, the oldest literary journal in Canada, and I wanted to know what she had done when she and Dennis Lee co-edited the production in 1960. I found her to be a wonderful, warm, funny, and engaging conversationalist. Interviewing her is, however, a different matter.

The key to interviewing Margaret Atwood, as Brian O’Riordan and I learned, is to show up prepared with a strategy to address major issues in her works. Our interview began badly. We opened with a question about a bird book she had written for children. She disappeared for about fifteen minutes. When she returned, we addressed her most recent book at the time, Cat’s Eye. That was when the interview became intense. We matched her idea for idea. She liked that. We challenged her and she challenged us. She later told me that she thought our interview with her was one of the best. When my first book of poems was published she wrote me a wonderful congratulatory letter.

Few authors, not only in Canada, but also on the world stage, have commanded such a significant amount of attention. Atwood has never backed down from a contest of ideas. When the tape recorder is on, she is very conscious of what she says. Her public image and her writing have become inextricably linked, and for good reason. She puts herself on the line for what she believes. In this respect, she is the most integrated writer I have met—a person whose public persona argues for reason, good sense, and the good earth. I admire her greatly for that. This is a portrait of the two Atwoods I am glad to have known.

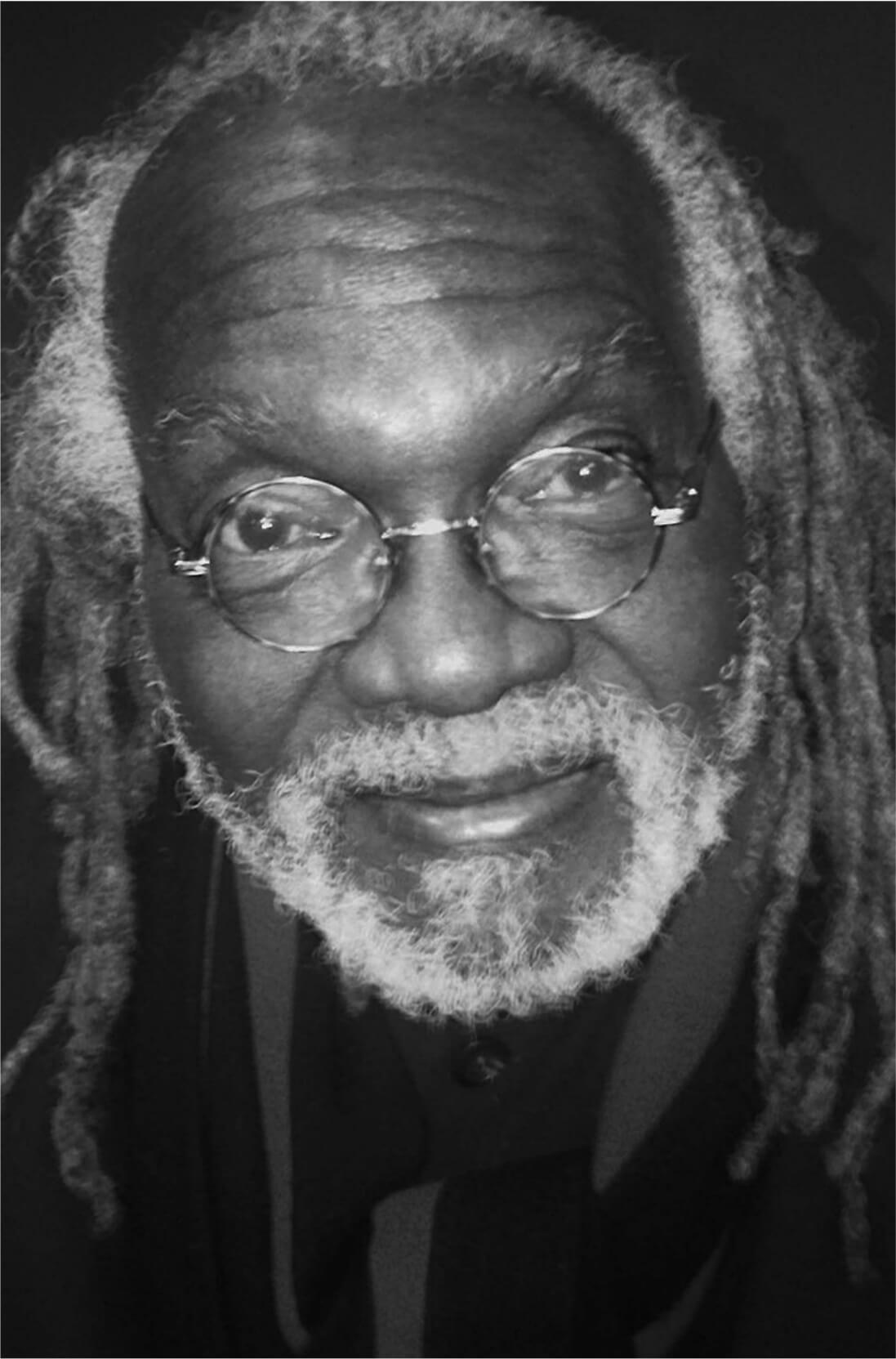

Austin Clarke

I photographed Austin Clarke in 2012 when he came to Barrie, Ontario, to give a talk at City Hall for Black History Month, but our friendship goes back many years before that. When I was an undergraduate, my friend Lawrence Hopperton was invited to a party at the home of novelist James Bacque. The party was in honour of a Scottish poet Larry knew. I tagged along.

Sitting by himself at the kitchen table and sipping a martini (London Gin, dry, twist of lemon, two olives dirty) was a face I recognized from a book jacket. I exclaimed, “You’re Austin Clarke,” to which he replied, “Be cool, man.”

Several decades later when I was beginning the creative writing program at the University of Toronto’s school of continuing studies, I telephoned Barry Callaghan to see if he had any recommendations for possible instructors. “Austin Clarke!” Barry boomed. “He’s been living on my couch and he’s sitting here stinking the place up with his pipe!” Austin got on the phone and I hired him immediately. That was the beginning of a good reversal of fortune for Austin. Shortly after that, his out-of-print backlist was purchased by several international presses, and he told me he was working on a new novel about Barbados.

Late one afternoon while I was at my U of T office, I received a panicked call from Austin. He had to get his manuscript for the new novel, The Polished Hoe, to his publisher, Patrick Crean, and he had no printer. Austin brought the book over on discs, but the files were corrupted and the paragraphs had run together. My assistant, Elise Gervais, pulled the sheets from the Xerox machine while I sat at my computer with Austin, crafting the paragraphs of the manuscript. That night we delivered the manuscript together (all 800 pages of it) to Crean, and Austin took me out for martinis at the Grand Hotel.

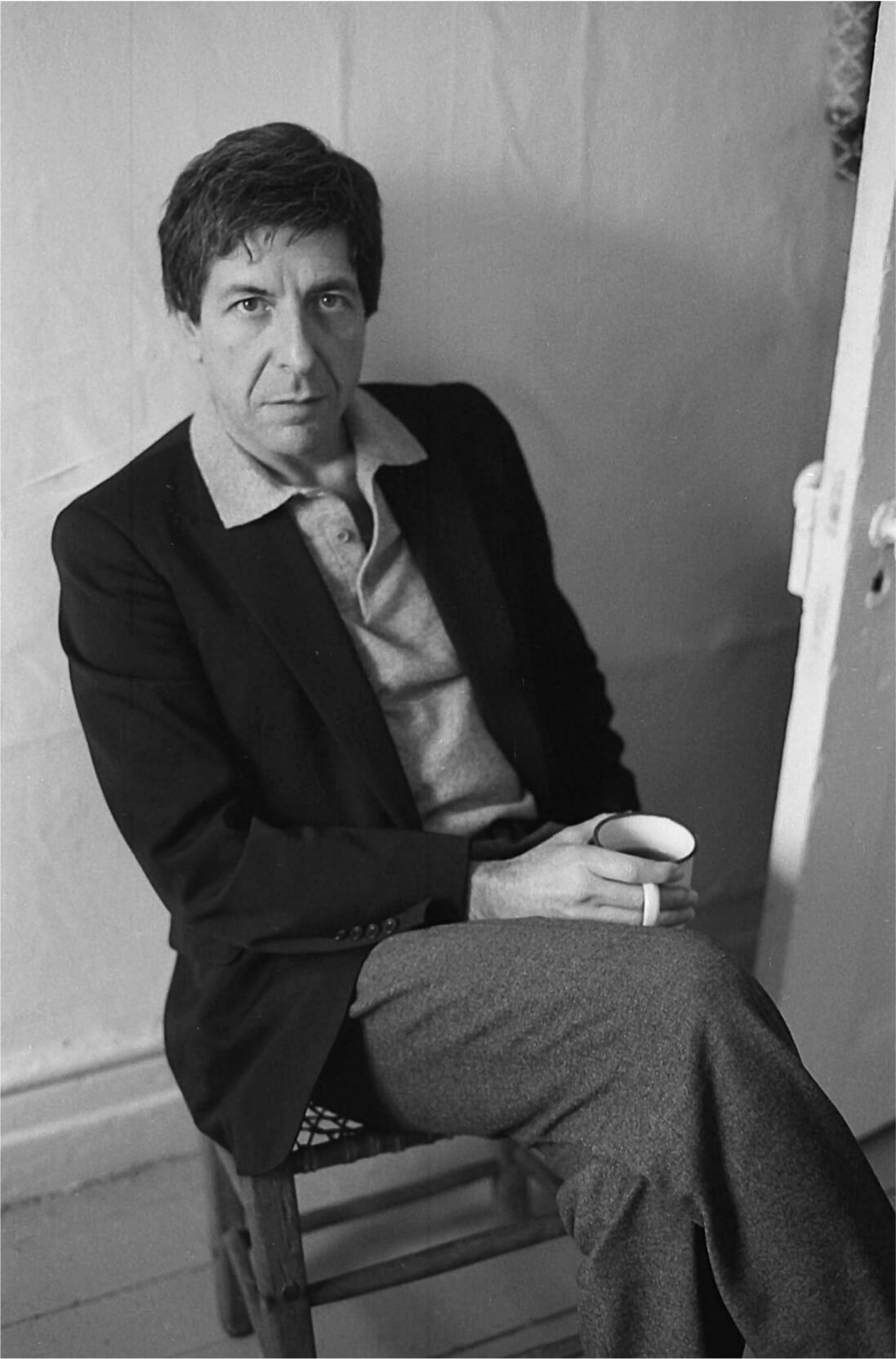

Leonard Cohen

Leonard Cohen had just returned from a self-imposed exile in a Buddhist monastery in California when Irving Layton suggested that Brian O’Riordan and I travel to Montreal to interview the sad-voiced troubadour. “He’s at a point of transition,” Layton said.

Our train was late arriving in Montreal, so we raced directly to Cohen’s place, the upper floor of a very low, flat-roofed, Victorian row house opposite the Parc Portugal behind Ste. Catherine Street. We had stopped at Queen Elizabeth Station to call to make sure he was there and he said “Come on over.” We knocked on the door. No answer. I reached up and knocked on his front window (the building was that low). Nothing. Suddenly, the door opened by itself. We stepped in. The door closed behind us.

I looked up the stairs and could see Cohen, in outline, at the top, the light behind him from an upper window. It was dramatic. I said, “How did you work the door?”

“It is on a string.”

“So the door is a kite?”

“Yes,” said Cohen, and together we both said, “and the door is a victim.”

Upstairs there was a spread of schnapps, matzah, kosher dills and Montreal smoked meat for us. He showed us around the four rooms of his pied à terre. On top of the electric outlet in the kitchen was a comb-drawing of Irving Layton. On top of the water heater was the bust of Layton that appears on Layton’s Selected Poems. I asked about the icons. “Irving is my poetic master,” he said.

In the main room, there was a long table, a chair, and Cohen’s guitar in its case, lying in state on top of the table. The only picture on the wall was that of a young First Nations woman. “That’s Kateri Tekakwitha,” he said. “She’s the love of my life.”

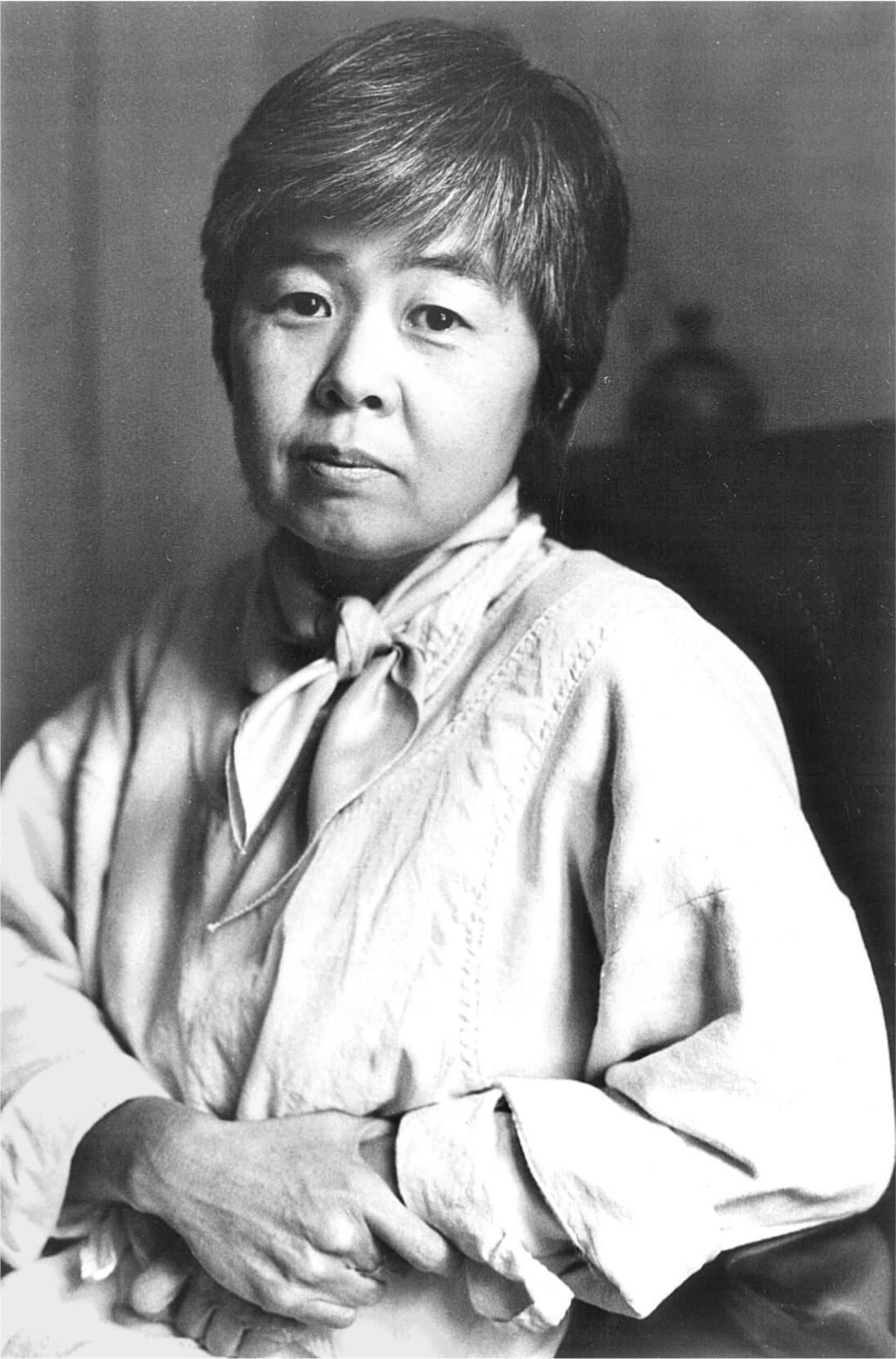

Joy Kogawa

In 1983, Joy Kogawa had just published her acclaimed novel Obasan, a work of artistic beauty and historical accuracy that led to the Canadian government’s apology and reparations to the Canadian-Japanese community for the treatment they had received during World War II. Based in part on manuscripts she had found in archives, and in part on her family’s experience during the forced relocation, Kogawa brought the plight of her community to life with tremendous empathy in one of the most moving novels written by a Canadian.

This photograph of Joy Kogawa was taken at her home in the north end of Toronto’s Little Italy district. When we arrived, she showed us a board game she had been given as a child, The Yellow Menace. It was a snakes-and-ladders type of game about beating the Japanese. We sat on tatami mats throughout the interview. What caught my eye as I looked through the viewfinder was the exquisite Japanese vase in the background, an object that is almost a shadow behind her.

Never one to shy away from confronting difficult issues and matters, Kogawa has served not only as an imaginative force for Japanese Canadians, but as someone engaged in Canadian politics and literature. Early in her career, she served on the staff of Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau; but her focus has been the passionate art of words, and deserves to be celebrated not just for her outstanding novel, but for her poetry and her children’s books. Shy and self-effacing, she is often the last person to admit the full scope and powerful impact that her work has had on Canadian culture, society, and history.

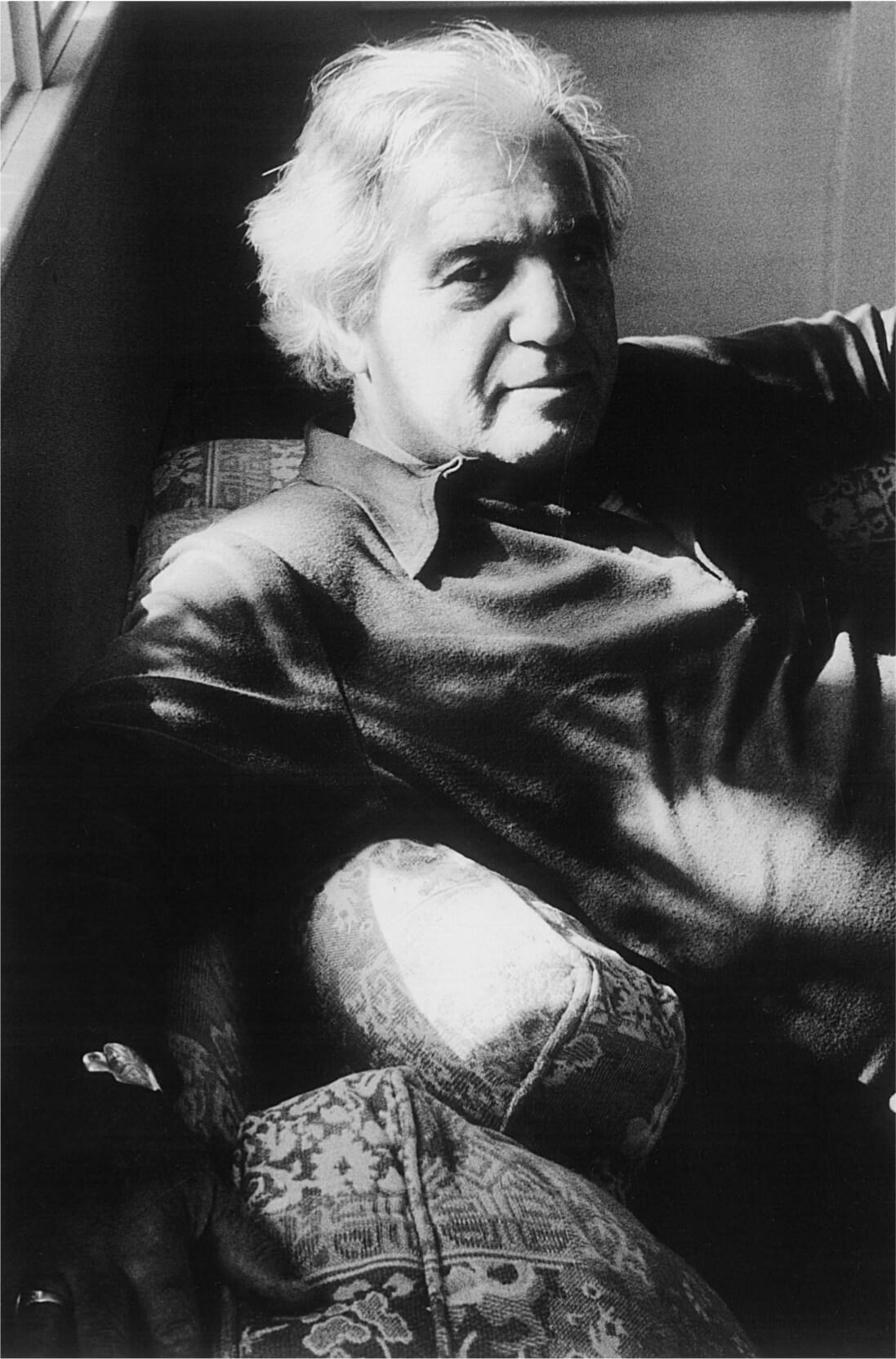

Irving Layton

Ralph Gustafson wrote a very short poem about Irving Layton: “Oyving’s / Unoyving.” That only sums up a small aspect of a man who was larger than life, whose poetry roared and often shook the foundations of Anglo-Canadian society, and who was one of the most artistically committed poets I have known. He was a teacher of Creative Writing at York University, and many of my poet and writer friends who passed through there owe their vocations to him.

I got to know Irving Layton when he was writer-in-residence at the University of Toronto in the early eighties. It was the interview with Layton that set Brian O’Riordan and I on our long journey through Canadian literature. Irving liked what we did when we interviewed him: we put his poems first and his press clippings second, and based our questions on that. He gave us Leonard Cohen’s telephone number, and that led to the two books of interviews we did and immersed me in this country’s literature. I owe a great deal to Irving Layton.

In person, Layton was playful, a man with a tremendous sense of humour that could become passion and even anger in an instant. He did not hide his emotions. When he got angry, his eyes would darken. When he laughed, he would throw back his head and roar. This photograph was taken while Layton was living in Port Credit, Ontario. I wanted to capture the mane of the lion, the light and darkness that inhabited his features, and the fist of the boxer he had been in his youth. His poetry is read today, long after his death, because when he was good there was no one of his generation who was his equal.

Gwendolyn MacEwen

When I photographed Gwendolyn MacEwen, I wanted to capture her eyes. To have known her, to have looked into those eyes as she talked about T.E. Lawrence or the mysteries of Egypt was to be reminded of the eyes that were painted on ancient Greek ships. She had a rare classical quality about her. When she presented her work in public, she would fold her hands in front of her, stand with her chin raised and her voice clear, and recite. She never had a note in front of her. She was, in the very truest sense of the word, a rhapsode, a singer of her own songs.

I would meet her as she rode her bicycle with its tiny wheels along the streets of the Annex near the University of Toronto. She would call to me and ask me to join her for tea. The front room of her house had a raised seating area lined with kilim cushions. The window was festooned in hanging plants. We would talk about poetry. She taught me a great deal about the art. One day she turned to me and said, “You are the son Milton Acorn and I would have had.” We burst out laughing, but it was a comment that I still treasure.

I didn’t know it at the time, but she read my poetry. She told me how much she liked it. Unbeknownst to me, the manuscript of my first book of poems, which had been rejected by over six hundred publishers all over North America, landed on her desk (courtesy of James Deahl, who went to visit her when she was writer-in-residence at the University of Toronto). She telephoned me on the final Boxing Day of her life (though, at the time, I didn’t know how ill she was). She told me she loved the manuscript and was sending it to Marty Gervais at Black Moss Press. The following October, a week after she died, I received the acceptance letter for my first book of poems.

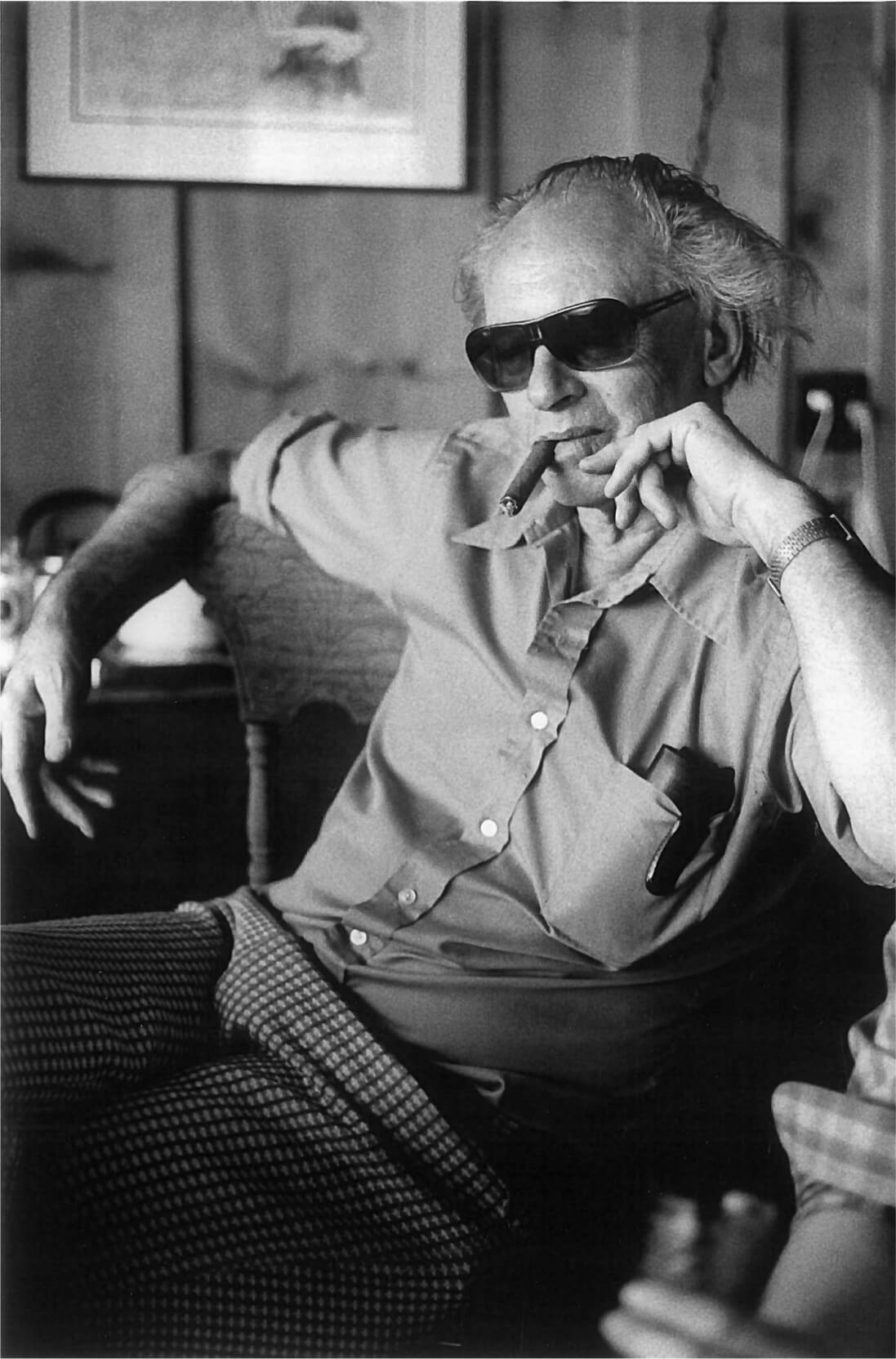

Al Purdy

We went to see Al Purdy at his home on Roblin Lake near Ameliasburgh, Ontario. The entire day was a fiasco. My parents gave Brian O’Riordan and me a lift to Purdy’s place and then went for a picnic. Purdy was well away on American beer by the time we got there. A large seagull, possibly an albatross, lay dying in the heat on his front lawn.

Purdy, as a poet and an individual, was protean. He was a shape-shifter. It was hard to get a straight answer out of him. He produced a bust of D.H. Lawrence and force-fed it a bottle of beer when I pointed out that I didn’t think it was much of a likeness of the British poet and novelist. “It looks a lot more like D.H. Lawrence,” he said, “than I look like Al Purdy.”

We sat at his kitchen table, where this portrait was taken as he smoked a cigar and rambled on about whatever topic he wished. I realized as I sat there, the table awash in beer, and our question sheets soaked in brew, that many of his best poems were written while he sat in that kitchen, looking across the lake at the church steeple that appears in “Wilderness Gothic,” or at the gap in the distant shoreline where Roblin’s Mill once stood.

I asked to use the washroom and he showed me to his front porch (the bird was dead by then), and as we stood there he showed me how to write my name on the earth. “This is how you mark your place in the world, and how you sign it.” At the time, I thought the whole experience was bizarre, but in retrospect Purdy was trying to open to me his very unique world—his love of this place, the earth he lived on, and the locations he knew. Several weeks later, I got a very contrite letter from Purdy. He was sorry about the interview. He sent the answers. He shifted shape yet again and that, in essence, is what summed up Al Purdy for me. He was as fluid as language.