No US election would be complete without Canadians declaring our moral superiority, so it has become commonplace to suggest that Bernie Sanders, the septuagenarian socialist challenging Hillary Clinton’s coronation as the Democratic presidential nominee, would not be so radical here. His playbook “is straight out of Canada,” Diane M. Francis writes in the Huffington Post. “It may have been Ted Cruz that was born in Calgary, but it’s Bernie Sanders who sounds most like a Canadian,” says Jack Mintz in the National Post. There is some truth to this—universal healthcare, of course, is Sanders’s big-ticket policy proposal, as well as higher taxes and a general redistribution of wealth—but it’s largely a smug fiction. Most of Sanders’s ideas lie well to the left of any major Canadian party, including the NDP. And that’s a problem.

To be sure, there is plenty of overlap between Sanders’s platform and the Canadian status quo, and, given each country’s unique legal and political systems, comparing the US and Canada is often a mug’s game. But on a few key issues the difference is telling. The NDP campaigned in the last election on affordable childcare and a $15 federal minimum wage, like Sanders, but those ideas went down in defeat. The Vermont senator’s advocacy of free postsecondary education, one of his cornerstones, is found on the platform of no major Canadian party—even though it is both sound policy and the right thing to do, as countries like Germany, Brazil, Sweden, and many others already know. (Only Québec solidaire, a small left-wing party with three seats in Quebec’s National Assembly, officially supports it.) Sanders is also a free-trade skeptic, a position the NDP, after years of hemming and hawing, has abandoned under Thomas Mulcair.

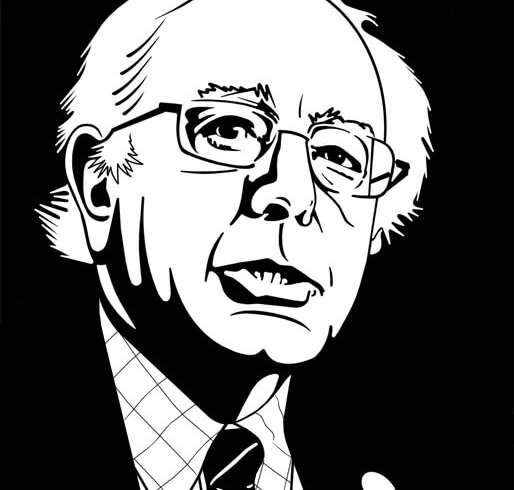

It’s Sanders’s rhetoric, however, that best illustrates just how far outside the Canadian mainstream he falls. He is, as he calls himself, a democratic socialist, and he has done a great deal to push that term, previously anathema, back into American politics. The NDP, however, excised “socialism” from the preamble to the party constitution in 2013, as part of Mulcair’s hard tack to the centre. If anything, Sanders most closely resembles the NDP of the pre-Jack Layton era, of Ed Broadbent and Tommy Douglas, and would have a hard time finding a home in the party today. Mulcair has sidelined old-guard left-wing MPs who represent a challenge to his leadership, and he is temperamentally incapable of the kind of fire-and-brimstone speechmaking that has made Sanders an unlikely star. You will never, ever hear Mulcair ranting about the “billionaire class.”

That may be because class disparity in Canada is less extreme, though inequality is still on the rise here, as it is around the world. But Mulcair’s chilly forbearance is also a conscious choice. All this would be a moot point if his strategy—trying to outflank the Liberals from the mushy middle—had worked. It didn’t. Justin Trudeau’s rout of the NDP in last fall’s election was made possible by the party’s drift away from its roots. The NDP’s historic strengths—health care, education, and the environment—are broadly popular, but there is little reason for voters to choose Liberal-lite when the real thing is so much more charismatic and compelling. Meanwhile, Sanders has taken the opposite approach, embracing radical ideas that pundits and wealthy donors have dismissed as unworkable. In so doing, he has proven that, even in the supposedly conservative US, there is still an appetite for big thinking.

As polls consistently indicate, young people have a much more favorable view of socialism, and a less favorable view of capitalism, than older generations. They grew up after the Cold War ended, yes, but they also came of age amid the economic upheaval, precarious employment, and skyrocketing income inequality of the early twenty-first century. Somehow, despite being seventy-four, Sanders has emerged as the figurehead of this moment—the first major American political leader in decades to talk so frankly about class and poverty and injustice. Whatever you think of him, he has tapped a deep vein of disenchantment that the Democratic National Committee, like its Republican counterpart, massively underestimated. Canada, on the other hand, has no such leader, no such spokesperson. It is unthinkable to imagine Mulcair drawing huge crowds the way Sanders does, or giving a voice to the frustration and despair that so many citizens feel.

After his early momentum in Iowa and New Hampshire, Sanders seems to be slowing down, and he is poised to lose in South Carolina this weekend. He will, in all likelihood, not be the Democratic nominee. There is plenty about him worth criticizing: his questionable electability, his flawed record in the Senate, his difficulty reaching out to voters of colour. (It must be pointed out, though, that the same criticisms apply to Clinton: her favorability ratings are poor, her convictions shift endlessly, and her hamfisted attempts at courting Latinos and African-Americans are legion.) But, even if he loses, Sanders is nudging the fulcrum of American political discourse, exciting the imaginations of huge numbers of young voters, and proving that social democracy need not be an unutterable phrase. Canada, the home of universal healthcare and prairie socialism, should not be left behind in this shift. We badly need a Bernie Sanders of our own.