2018marked the fiftieth anniversary of what I think of as the last great revolution—the chaos of 1968, when the Vietnam War began to turn, student protests erupted, and the Prague Spring came to a crushing end. Today, North America is facing not one but two revolutions: a revolution of possibility and a revolution of negation.

This may not feel like a particularly revolutionary time. But, if we look closely, we can see current economic, social, and political forces pulling us in two directions. One direction will accelerate us forward, the other backwards. We will decide our fate by the revolution we embrace.

The revolution of possibility is driven by education, science, innovation, and design. It is a cluster of scientific and technological revolutions, all feeding one another. It is about access to wealth, health, and personal freedom.

The revolution of negation is driven by superstition and fear. It is a different sort of cluster—of ignorance, despair, greed, racism, and hatred. It is about shutting other people out and protecting only ourselves. In one version of events, we act collectively; in the other, we hoard our wealth and act alone.

To the champions of the revolution of possibility—including designers, programmers, artists, innovators, and entrepreneurs—nothing is more exciting than a world improving itself. Our daily lives can be smarter, faster, easier, lighter, greener, more equitable, more open and accessible, and more beautiful. From the energy we use to the products we buy, from the food we eat to the ways we interact with our environment and with one another, everything is being redesigned to better meet our needs.

The revolution of possibility is exponential, and it is accelerating. Everything is unstable, dynamic, transformational—a condition that is deeply unsettling for many people. “If you’re anxious, imagine how the folks who aren’t in this room are feeling,” Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told a group of business leaders at the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in 2018. “Workers, people who aren’t seeing the benefits of economic growth, regular women and men who are trying to grab a rung on the career ladder, never mind climb it—for them, technology is a benefit to their personal lives but a threat to their jobs.” Technological change is destabilizing—one recent report concludes that automation could displace an estimated 400 to 800 million people by 2030. No one knows which jobs will exist in fifteen years. But we do know that the revolution of possibility is also accomplishing feats beyond our imagination.

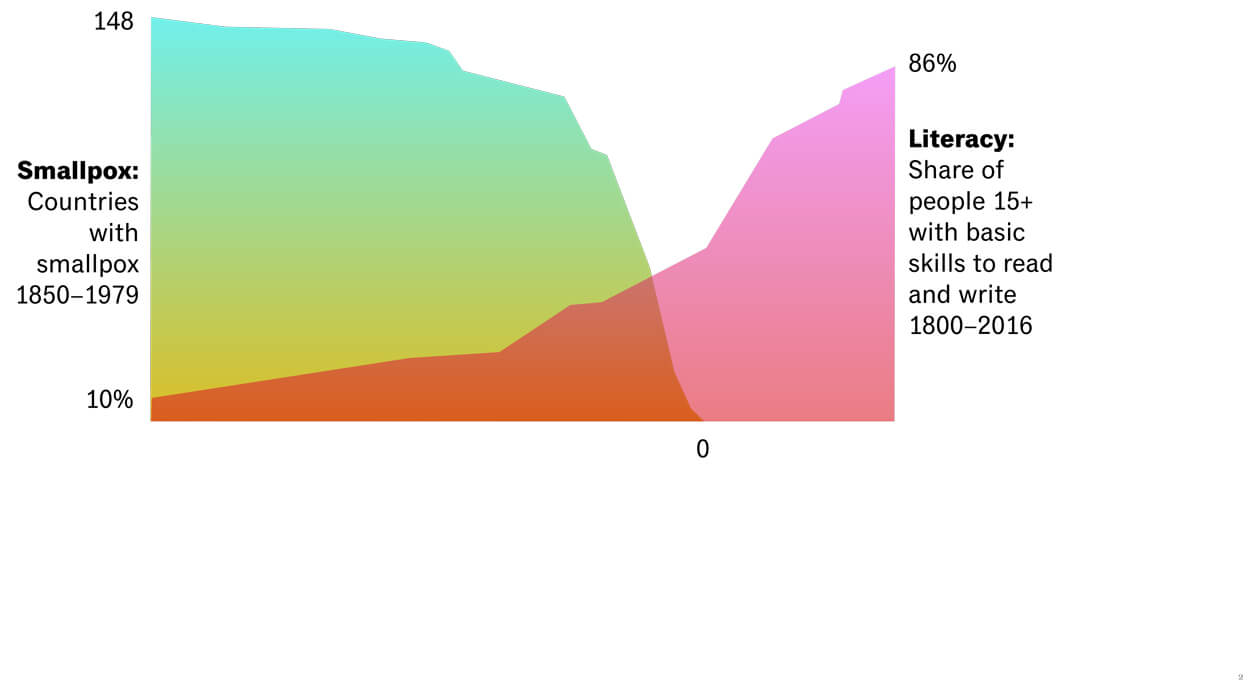

Over the last 200 years, we have seen a positive inversion in almost every measurable trend that matters. Grand challenges, from managing the spread of infectious diseases to providing free public education, have been confronted. We landed on the moon. Now we have a workforce in space on an international space station, we drive a rover around on the surface of Mars, and big freaking rockets take off and land themselves. Collectively, many of the world’s countries have organized efforts to confront polio, malaria, HIV/AIDS, Ebola, climate change, poverty, and hunger. We built a global infrastructure of manufacturing, transport, air travel, and telecommunications. More than 4 billion people now have access to the internet, providing them with opportunities and enormous amounts of information, and agricultural output has more than tripled since 1961.

Somehow, many commentators are convinced that we are falling behind. “Trust is collapsing in America,” The Atlantic announced in January 2018, noting declining trust in government, media, and businesses. In an Ipsos poll in 2017, more than half of the Canadian participants agreed that young people today will be worse off than their parents’ generation. We are convinced that we are not succeeding, that our institutions are failing, that we are not capable of putting global welfare ahead of personal or nationalist gain, that we are not willing to learn and change our behaviour to ensure the advancement of human society.

In 1820, an estimated 94 percent of all global citizens lived in extreme poverty. The difference between rich and poor was profound. It was the difference between king and pauper. Today, Warren Buffett is one of the richest people in the world, but while he has access to opportunities I do not, we live more or less the same way. We both have access to education, we fly in airplanes, we travel for pleasure, we have cell phones, we have computers, we have the internet, we drink Starbucks, and we use Google. As Andy Warhol once pointed out, the president (and, in this case, Warren Buffett) drinks the same Coke that I do. Technology—air travel, international shipping, consumer electronics, the internet—has allowed billions of people to share the same experiences. The revolution of possibility is radically egalitarian and built on a platform of open connection; it should be accessible to everyone. This access to possibility for billions of people worldwide is the defining quality of our time.

Yet some of us are actively denying it, cutting the rungs off the ladder we climbed. There is a risk that the benefits of our highly connected age will go only to the lucky few. I believe we are faced with a choice: return to the familiar patterns of our past or take a leap into a radical and uncertain future.

In his 1957 Nobel Prize lecture, future prime minister Lester B. Pearson referenced the historian Arnold Toynbee, who said that in the long sweep of history, “the twentieth century will be chiefly remembered by future generations not as an era of political conflicts or technical inventions, but as an age in which human society dared to think of the welfare of the whole human race as a practical objective [emphasis mine].” When Toynbee used the term practical objective, he set the parameters for a historic design project—not a utopian vision, which is by definition out of reach, but a goal that everyone is capable of committing to.

ECONOMY

Embracing the revolution of possibility will mean liberating humans from dangerous and mindless work. Automation may seem terrifying—after all, almost half of the work done in Canada has the potential to be automated, according to the Brookfield Institute for Innovation and Entrepreneurship. But jobs that involve creativity, social interaction, and a human touch are hard to automate, and they’re much more fulfilling than the work that robots do best. Automated vehicles could put nearly 300,000 Canadian truck drivers out of work, but automated vehicles can also prevent thousands of people from being killed annually by human drivers. Automation doesn’t come without its costs. It will disproportionately affect people in the lowest income brackets, so we must build systems to help workers retrain and survive unemployment.

The last fifty years have seen the greatest creation of wealth in human history. Billions of people have entered the global middle class. This group now includes 3.8 billion people, according to one study—for the first time, outnumbering the poor and those in poverty. New forms of payment and economic exchange are also providing the poorest access to the riches of the market. M-Pesa, a Kenyan mobile payment service, has been credited with lifting 2 percent of Kenyan households out of poverty simply by providing banking they could access. This is the revolution of possibility: making opportunity accessible to all.

The revolution of negation, on the other hand, means desperately holding onto outmoded technologies, industries, and energy systems regardless of the economic, ecological, and human impact. Countries in the G20 provide $444 billion in subsidies to fossil-fuel companies (in 2016, Canada gave $3.3 billion to the industry). President Donald Trump has insisted on the importance of saving the US coal industry, despite declining demand for coal, and his administration has rolled back dozens of environmental regulations, including safety rules for offshore drilling.

The revolution of negation also means greater and greater concentration of wealth in the hands of fewer and fewer people, with 1 percent owning over 40 percent of the world’s wealth. Since 1980, income inequality has increased rapidly in North America, Russia, China, and India and moderately in Europe, according to the 2018 World Inequality Report. In the areas where it hasn’t grown, inequality was already extremely high—the richest 10 percent in the Middle East continue to own about 60 percent of the wealth. Even in Canada, a country with a standard of living idealized by many, the wealthiest eighty-seven families have a net worth equivalent to everyone in Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick combined. There is a risk that the wealthiest citizens will live in ways completely separate from the rest of us and lose connection to their communities. The future lies not in gated communities and VIP lounges but in platforms that can make the benefits of our age open to all.

HEALTH

The definitive metric of life is death. How long we live is an undeniably final measure of our access to health information, health services, and healthful environments. Worldwide longevity has been increasing for the last 200 years. Lifespans have increased faster in some places than in others, and they have occasionally declined in times of crisis and conflict. But the overall trend is clear. Technological and scientific progress have increased our capacity for medical intervention, leading to new forms of health care, lower infant mortality, and greater longevity. This is the revolution of possibility: greater access to health and to a higher quality of life. The sector of health care innovation is constantly imagining and delivering new technologies of intervention to the human body.

We can now replace or repair arms, legs, hands, joints, teeth, eyes, hearts, kidneys, skin, ears, pancreases, bones, cartilage, livers, and lungs. Massachusetts Institute of Technology prosthetics innovator Hugh Herr, who lost both legs below the knee while mountain climbing, has joked that he feels sorry for people who can’t upgrade their limbs. His prosthetic legs keep improving—he now has special pairs for running and climbing—while the rest of his body, like those of all humans, ages. He sees a future where prosthetics will not only replace but improve human bodies and may one day be preferable to ordinary flesh and bone.

When humans work together, we can wipe diseases from the face of the planet. Smallpox became the first disease to be declared eradicated, in 1980, after an enormous campaign led by the World Health Organization with international advisers from over seventy countries. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which provides billions of dollars to efforts to improve global health, predicts that we could eliminate four more diseases by the year 2030, including polio and guinea worm. Malaria will not be eliminated, but its spread could be greatly reduced by then. Cases of polio have dropped by at least 99 percent since the polio-eradication effort began in 1988.

Meanwhile, the revolution of negation is actively denying science in favour of pseudoscience and conspiracy theories. Since 2009, the number of “philosophical belief” exemptions from vaccine programs has risen in twelve states in the US (only eighteen states allow such exemptions). Measles have returned after virtually disappearing. After antivaccine activists visited a community in Minnesota, around 2008, the vaccination rate dropped to a dismal 42 percent by 2014. Three years later, the greater community was hit with a total of seventy-five cases of measles, almost all in children under ten years old. Fort MacLeod, a small town in Alberta, also has a startlingly low vaccination rate—possibly the result of resistance from local church leaders. Antivaccine sentiments have spread through Europe. Unsubstantiated rumours about the effects of vaccination are amplified and given new life online, especially through social media. New technology, in this case, gives voice to groups committed to spreading fear and undermining the very foundations of truth and expertise.

FREEDOM AND DEMOCRACY

The revolution of possibility promises access to political freedom and a profound shift of power into truly democratic social and market mechanisms. It means the support of free movement, free speech, and a free press.

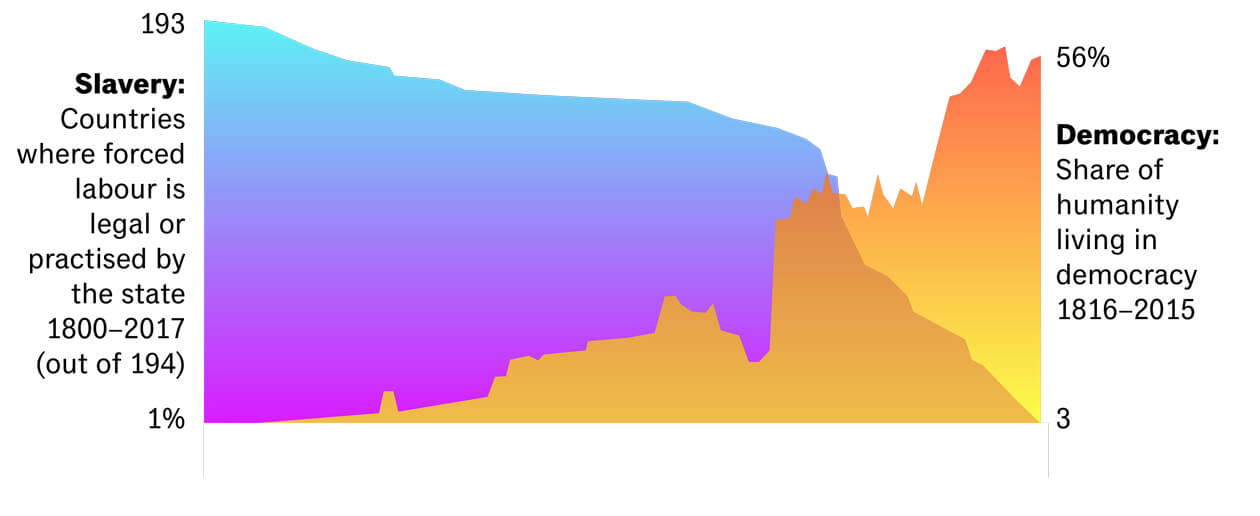

The share of democracies among the world’s governments has been rising since the mid-1970s, and nearly six in ten governments were democratic in 2016, according to the Pew Research Center. That’s a massive accomplishment, considering that 200 years ago there was only one official democracy (the United States), and even then, voting was restricted mainly to propertied white men. Political violence has declined enormously in the past seventy years. In Canada, there’s more civic engagement: more Canadians are members of groups in their community, and according to 2013 numbers, more than half of the people in political and cultural organizations use the internet to participate. The internet, and all the platforms it enables, allows us to take part in democracy at an unprecedented level.

It may not feel that way, and for good reason. There has been a slump in global freedom in the last decade, with Turkey, Poland, Venezuela, and Hungary sliding toward authoritarianism. Online funding, social media, and video platforms have been used not to bridge divides but to launch campaigns of hate. Members of Myanmar’s military used Facebook to incite violence against the Rohingya in a manner reminiscent of the use of radio during the Rwandan genocide. Far-right parties in Europe have similarly used social media to stoke fear about immigrants and push for the closing of national borders.

Free speech is also under threat. An assessment by Freedom House, an independent US-based watchdog agency, between 2016 and 2017 found that thirty of sixty-five governments tried to control online discussions. In Turkey, more than 180 media outlets and publishing houses have been closed down. Leaders like Donald Trump and the Philippines’s Rodrigo Duterte have escalated their antimedia rhetoric, with the latter calling press freedom “a privilege” and claiming journalists who were killed must have “done something” to deserve it. In these trends, I see the revolution of negation, in which leaders preying on fear claw back civil rights in the name of nationalism and security.

Why does this matter? For better and for worse, we are all interdependent with the rest of the world. The long-term success of the citizens of one country is vitally dependent on the success of all countries. Ideas, goods, and people move quickly across the world today. Our biggest problems—economic, medical, political, environmental—transcend borders. People do too: whether refugees fleeing persecution (or the effects of climate change) or immigrants moving for work. By 2036, one in two Canadians could be an immigrant or a child of an immigrant. We must not hide or put up barriers but rather embrace a world where cultures, races, and languages mix to create new forms of wealth and beauty.

CLIMATE CHANGE

Climate change most starkly represents our diverging options. The most recent climate report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that we have only eleven years to prevent devastating flooding, droughts, and refugee crises. If temperatures rise by two degrees, 99 percent of tropical coral reefs will die, a fifth of insects will lose more than half their habitats, and millions of people will be forced to evacuate from tropical areas to escape flooding and drought. Limiting the rise in temperature to 1.5 degrees or less—a goal outlined in the report—would require a collective effort to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

It’s easy to feel pessimistic when faced with such dire predictions and consequences. But, while we are often poor at anticipating problems, we have proven that we can act on a crisis when it is on our doorstep. There is good news: individuals and governments around the world are taking action. A non-profit based in Michigan has been cloning redwood trees and planting the saplings as a step toward bringing back the ancient forests. More than 1,000 volunteers, led by a young lawyer, cleaned up 3.5 million kilograms of garbage from a beach in Mumbai. China has announced plans to build an enormous carbon market, and India now has the largest market in the world for auctioning renewable-energy projects. This coming decade could be a turning point in our history, and we will come to understand that our collective fates are intertwined.

The two revolutions I have outlined may seem like a simplistic model for a complex, ever-changing world. But they help clarify the way forward. We must find ways to trust one another and commit to global well-being, not just the betterment of ourselves, our city, or our country. In the end, all of us will have the right to choose our revolution, and by extension, every country and region will also make its choice. But unless we choose together, unless we collectively see and embrace the revolution of possibility that lies ahead, we will default to the revolution of negation. We will have lost our opportunity.