Kish Island—There is a main mosque on Kish Island’s north shore: a brick building with twin minarets sitting right next to a sandy beach on the Persian Gulf. From the palm-lined road nearby, the mountains of Iran’s southern coast are visible. But any shadow cast by Tehran’s repressive regime barely seems to reach Kish’s gentle sand. On this small island, eighteen kilometres off the southern coast of the Islamic Republic of Iran, it is far easier to find a five-star hotel than a mosque. That’s because Iran’s dictatorial government is trying to showcase Kish not as a strict Islamic haven, but as an earthly paradise designed to win over the international community.

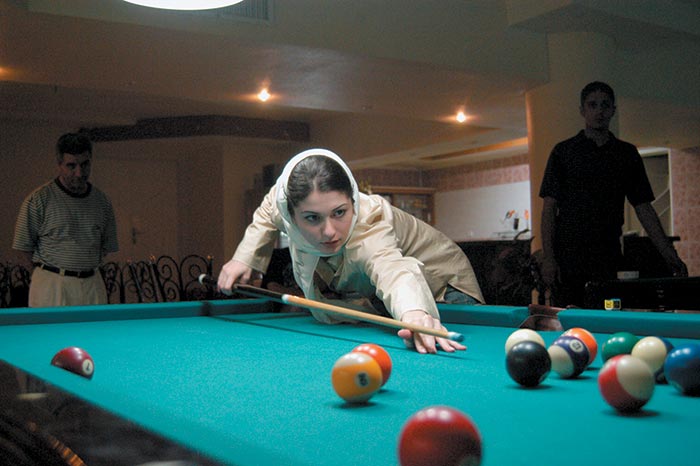

Kish (pronounced “quiche”) is a free-trade zone, a booming hub for business where no visas are necessary, a convenience unthinkable elsewhere in Iran. It is Iran’s Casablanca, Las Vegas, or Riviera—albeit with less fun. One can barely take a step without bumping into a hotel. There are almost sixty of them on an island just five kilometres wide and seventeen kilometres long. Paradise Mall and the Kish Hyper Market are hushed and gleaming centres, where Iranian families push around strollers, chat, and drink coffee in the sunny atriums. Women wear headscarves as if they were fashion accessories, as they walk briskly in high heels past stores selling everything from Samsung electronics and Cartier jewellery. “We’re going to have an eighteen-hole pga golf course,” says Behzad Shahandeh, an adviser to Kish’s government. He’s also talking about building a Formula One racetrack. “Why not? ” he asks.

Iran’s austere government is trying to give Kish a Western face, and the most dramatic evidence is a whispered plan to allow liquor to be served to foreigners at a yet-to-be-constructed resort hotel, known as the Flower of the East—this in a country where people are still flogged for imbibing. On the mainland, an elderly man recently caught drinking was too frail to survive the normal punishment of eighty lashes, so, in an adaptation of Sharia law, the court ordered that eighty whips be tied together, and the geriatric drinker be struck once instead.

Tehran’s harsher influences are not entirely absent from Kish. A contingent of Pasdaran, the revolutionary guards who prop up the regime, has a base here. Near the airport, giant domes conceal Iran’s electronic intelligence-gathering system. And businessmen are warned that every phone call is monitored.

For those who run Kish, it’s like straddling a barbed-wire fence. “We don’t go against the slogans that they say in Tehran, because we cannot,” says Shahandeh, who is a thoughtful professor of Chinese language and culture. “But we try to take the liberal road, the middle road. We can experiment with things on Kish. If things work out here, then we can move it to the mainland.” One female resident mentioned the possibility that the United States might bomb Iran. “Good! I hope they do,” she burst out. “All the young people will be happy. We hate this government.”

For outsiders like Simon Durham, a Canadian who works for the Quebec-based company dac Aviation International, “Kish seems like a combination of Phoenix and a giant shopping mall.” He was one of dozens of foreigners at the Iran Air Show. It was a bizarre event for a nation widely believed to be building a nuclear bomb, ruled by mullahs set on exporting Islamic revolution, and thumbing its nose at US foreign-policy demands. People in Kish believe that the US objectives for Iran are regime change and, then, ending the nation’s pursuit of nuclear weapons. At the air show, an Iranian helicopter hovered overhead, displaying the slogan “Death to America.”

Inside the exhibition hall, noise from 106 display booths dinged like a video game arcade. A Ukrainian general toured with his entourage, while mullahs in white turbans and robes walked with dignity, their hands clasped behind their backs. It was here that I met Durham. dac, he said, does business in some of the dicier parts of the world. “We started by leasing planes to the UN World Food Program, moving cargo,” he said. Here in Iran, though, Durham is hawking a system that reduces wear and tear on plane engines. “If the market opens up,” he said, the Iranians “will want to know who to approach.”

One who approached him was an Iranian named A.A. Moazzezi. “What we do is extend the life of the [helicopter] blade,” Durham explained to him, “by applying titanium nitride.” Moazzezi, it turned out, is an engineer for an arm of the Iranian military called Iran Aircraft Industries—a company designated on the US-based website, iranwatch.org, as a “suspect entity.” (Another firm at the show—with a similar name, Iran Aircraft Manufacturing Industries—has been “identified by the British government as having procured technology for weapons of mass destruction programs.”)

Durham, in other words, was talking with a representative of a firm suspected of having a role in Iran’s procurement network—although Moazzezi denied any knowledge of such affairs. Instead, amidst the clamour, he pointed to a table of civilian and military spare parts. His job, he said, is to make sure the military can repair its arsenal of planes while under a US embargo. Iran has a fleet of US-made F-14s, F-5s, and F-4s that date back more than a quarter-century to when the country was a client regime of the United States. Back then, Kish Island was a playground for the fun-loving Shah. But since the ayatollahs climbed into the pilot’s seat in Tehran, the US has refused to sell them spare parts, and has arrested Americans attempting to do so.

Certainly, Iranian purchasers were using this air show to find new black-market suppliers. One French businessman who refuses to sell parts to the Iranians rolled his eyes in frustration. “We had hundreds of people,” said Jean-Louis Haas, a salesman with tat Industries. “They ask for support and parts.” He laughed, holding his hands together as if in handcuffs. “I don’t want to go to jail! So I don’t sell the parts.” Even if, he added, “under the table you give me a glass of wine.” Still, the parts get through. “We obtain them,” one Iranian official smiled, “but I do not know how!”

In fact, at least half a dozen other companies at the air show were on the “suspect entities” list. The Aerospace Industries Organization of Iran had a large display of gyroscopes and missiles. “We are a military organization,” said the export manager. When I mentioned that his firm is listed as a suspect entity, he responded: “You know, I’m not really in charge to answer this question. I don’t know what part of the missiles we produce.” But he did confirm that his organization is headed by a general from the Iranian Revolutionary Guard.

Arms sales from EU countries to Iran are banned, but you wouldn’t know it from the displays. At one booth, a French firm’s brochure advertised tank helmets and an armoured vehicle intercom. The salesman, irritated by my questioning, snapped, “That is not for sale. It is just in the brochure.” A nearby stall was adorned with photographs of pilots standing jauntily next to fighter jets. François Leloup, representing a French company called Aerazur, said he had a $100,000-a-year contract with the Iranian air force. “I thought military equipment was not supposed to be sold,” I said. It’s military equipment, he confirmed, for fighter pilots, helicopter pilots, and aircrew. Because he was also selling life jackets and survival gear, it was allowed, he explained. Here in Kish, it seems even international embargos are pliable in the name of free trade.