SOCIETY / JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2024

Invisible Lives: Meet Canada’s Undocumented Kids

Without legal status, these young people must live in the shadows

PHOTOGRAPHY BY CINDY BLAŽEVIĆ

TEXT BY NICOLE DIRKS

Published 6:30, Feb. 2, 2024

“You feel like you’re hiding in plain sight,” Lisa said, on growing up undocumented—in her case, without proof of residency or citizenship. She was five when she arrived in Canada from the Caribbean, but she didn’t know she was undocumented until her teens. School became a game of avoidance. The government had already rejected her family’s application for permanent residency and confiscated their papers. Since she’d been in the country so long, peers assumed she was a citizen. But, in secret, she was missing out. She’d skip sports tryouts: without Ontario health insurance, treatment for any injury would need to be paid for out of pocket. Since university wasn’t an option, she avoided guidance counsellors. She chose friends carefully.

Undocumented youth in Canada are similar to so-called DREAMers in the United States—but without anyone officially knowing they exist or how many there are. Estimates range between 20,000 and 500,000 persons. For accurate data to be collected, people would have to admit their situation and risk being deported. Even an application for status is dangerous. If rejected, they could be sent back to where they were born—a place with a language they may not speak and where they may have few ties. Applying also puts their families at risk, as names and addresses may need to be disclosed. While secrecy protects the undocumented, the lack of public awareness also keeps the issue off the government radar.

Canada offers specific immigration pathways for construction workers, caregivers, health care workers, entrepreneurs, and agricultural workers. But none for kids. This deficiency is where Sarah Pole comes in. Founder of the Childhood Arrivals Support and Advocacy Program, she helps Ontario youth assemble dense application packages that detail evidence of a life in Canada. Many clients apply for permanent residency on “humanitarian and compassionate grounds,” essentially pleas to be allowed as exceptions to immigration requirements they can’t meet.

Many people Pole works with have not had any say in coming to Canada. “Kids deal with the decisions other people made,” she says. Those kids spend most of their childhoods in Canada, where they do their schooling, form relationships, and build career aspirations, like everybody else. “It’s just this piece of paper thing—that is the difference,” says Pole. This “piece of paper thing” shuts folks out of colleges, universities, and trade schools: those who are not citizens or permanent residents generally require a study permit and must pay international fees to attend post-secondary institutions, and provincial aid often isn’t an option. It’s also a barrier to more basic rights, like access to health care and secure housing.

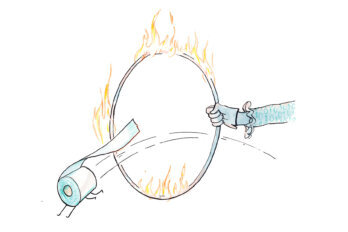

After years of working under-the-table jobs, Lisa finally achieved legal status with help from CASA (her name has been changed to protect against any lingering stigma). Cindy Blažević, a Toronto artist devoted to the intersections of identity, statehood, and immigration policies, grew interested in the plight of other undocumented youth and worked with CASA to coordinate a photo series showing clients holding objects of personal significance. The series is an expression of their invisibility and collective identity. “Just as they are camouflaged in plain sight in their daily lives,” says Blažević, “so they are in these portraits.”