Amid all the testimony and grappling with the past, the conclusion of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission prompts us to consider what physical traces remain of Indian residential schools. St. Paul’s. Shubenacadie. Edmonton. La Tuque. St. Michael’s. Muscowequan. Yellowknife. St. Anne’s. Spanish. Elkhorn. Birtle. MacKay. Camperville. Portage la Prairie. More than 140 existed, from coast to coast to coast.

These were real buildings that stood in real places. Consider your own early moments, which carry smells, sounds, and images. Visceral memories rise to the surface when you return to a familiar place. For many, residential school sites call up an entire childhood, bound in commanding institutional architecture that smells of chalk and disinfectant. Between 1883 and 1996, 150,000 children were forced to attend these schools, which were typically structured with a central chapel and separate areas for boys and girls.

Some buildings have been destroyed—intentionally by the community, accidentally through fire, angrily in some act of vandalism. In many cases, people have gathered to mourn, to celebrate, to heal, to cleanse. To leave these places behind.

Other buildings are succumbing to the gradual process of decay. Abandoned and derelict, their slow ruin mirrors the slow work of exposing what happened and recovering from it. Some argue their presence is essential. How else can we prove what happened? These sites are the proof. They are places we can visit, places to hear the stories. Places to figure out how we will go forward from here.

Still other buildings have been transformed. They host band offices or educational programs; they reclaim traumatic histories for the benefit of the community. In the former Assiniboia Indian Residential School in Winnipeg, for example, an agency works to protect the well-being of children. The former Mohawk Institute in Brantford, Ontario, houses a cultural centre that co-presents the world’s largest multidisciplinary Indigenous arts festival. In one remarkable case, a girl who attended Shingwauk Indian Residential School in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, is now the chancellor of Algoma University—established on that very site.

At first glance, a few bricks might be mistaken for a set of books. Either seems out of place in a vast expanse of windswept prairie. They are all that is left of a supposed place of learning. But they are also remnants of something larger.

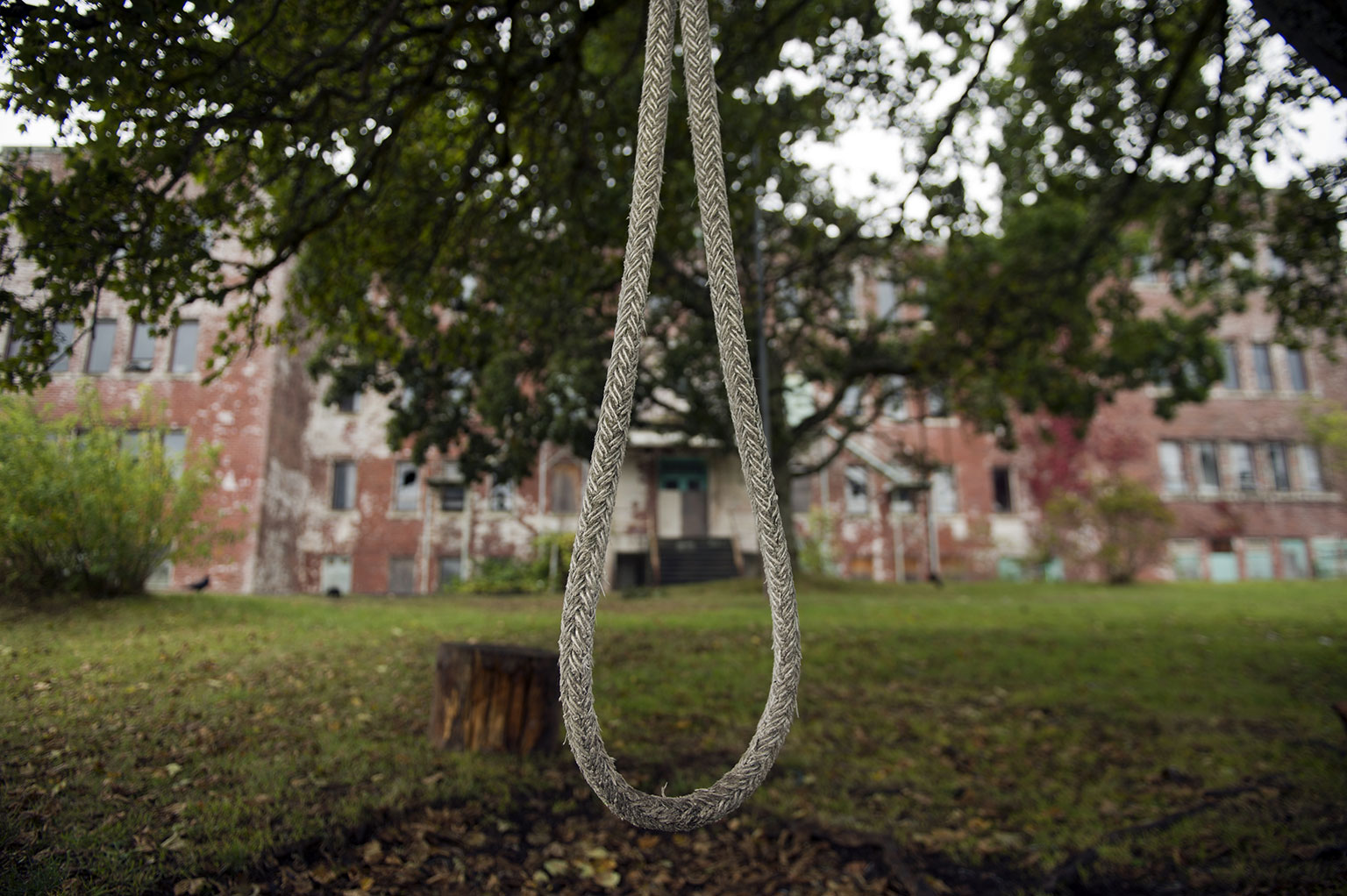

A loop of rope hangs from a tree in Alert Bay, British Columbia. It’s part of an old swing, worn down by the weight of children moving back and forth, enjoying a little escape. But it is also an unexplained, ominous evocation of death—of young students in care, of adults who could no longer carry the darkness, of their children who were forced to shoulder the burden of pain, shame, and isolation.

A window frames a cloudy sky. The view is punctured by ragged glass, damage caused by a bullet or rock or some other projectile. A former student and a late-night drive-by. An afternoon stunt by some passing teenagers. Vandalism that’s not senseless, but rather a symbolic ejection of anger that broods like an unwelcome stranger.

A crooked shed stands against the sky in Birtle, Manitoba, warped by wind and age. The reclaimed earth is suffused with a sense of abandonment, but children once worked these fields. Atop twisted planks, the shed’s roof seems insupportable, poised for an imminent collapse. But collapse is also a kind of release—tension escaping a rotten structure.

Handprints and a small footprint appear on the back door of Muscowequan Indian Residential School in Lestock, Saskatchewan. Someone actively refused to be passively marked by this place. It’s an act that speaks to the strength and resilience of those who continue onward even as these buildings deteriorate.

There is something reassuring about these crumbling, disintegrating sites. Time passes. Things change. Can the paternalism that built these buildings also wear away and make room for new beginnings? There’s a dilemma, of course. If the memories of what happened wither away, maybe it will mean things have gotten better. Or it will mean that people have forgotten, and that they are capable of making the same mistakes again. Forgetting helps some people heal. Remembering helps others learn.

Challenges remain for First Nations, Metis, and Inuit children. Failure rates, dropout rates, and suicide rates all are too high. This is the legacy of Indian residential schools: these buildings still loom in many communities. Twenty-first-century classrooms need to foster—not assault—Indigenous communities, individuals, cultures, languages, and knowledge.

All Canadians need to look for what cannot be seen in these pictures alone. People’s lives were touched, scorched by these places. Tuberculosis killed too many children. Others were punished with electric shocks, or strapped in public with their pants down. In 1937, four young boys froze to death trying to run away from the Lejac Residential School. There are many stories like theirs, and these images remind us that we need to hear them.

Civilization. Assimilation. Integration. Reconciliation. Evolving rhetoric. Aggression. Violence. Racism. Legislation. Repression. Omission. Oppression. Colonialism. Cultural genocide. What terms are you comfortable using?

Education can give us hope, and we are hopeful educators. Hopeful for today’s and tomorrow’s First Nations, Metis, and Inuit students. Hopeful that all children will learn about Indigenous histories and perspectives, because testimony is more than an individual responsibility. It is a collective one. Hopeful that all Canadians—young and old, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, in school and out—will acknowledge the physical remains of residential schools as powerful sites of memory and remembering, and will work to build something better.

—Aubrey Jean Hanson and D. Lyn Daniels

The Writers’ Trust of Canada supported the authors of this piece.

This appeared in the September 2015 issue.