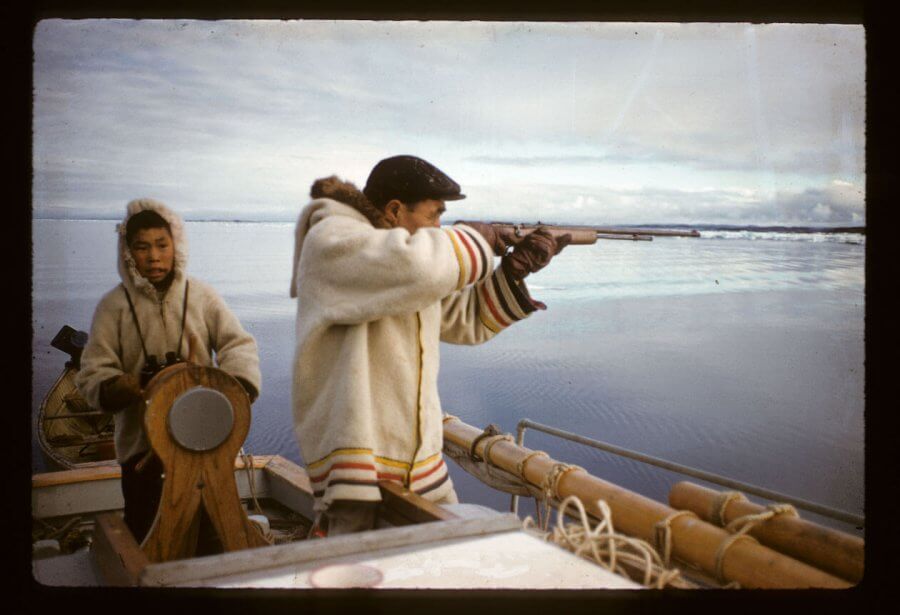

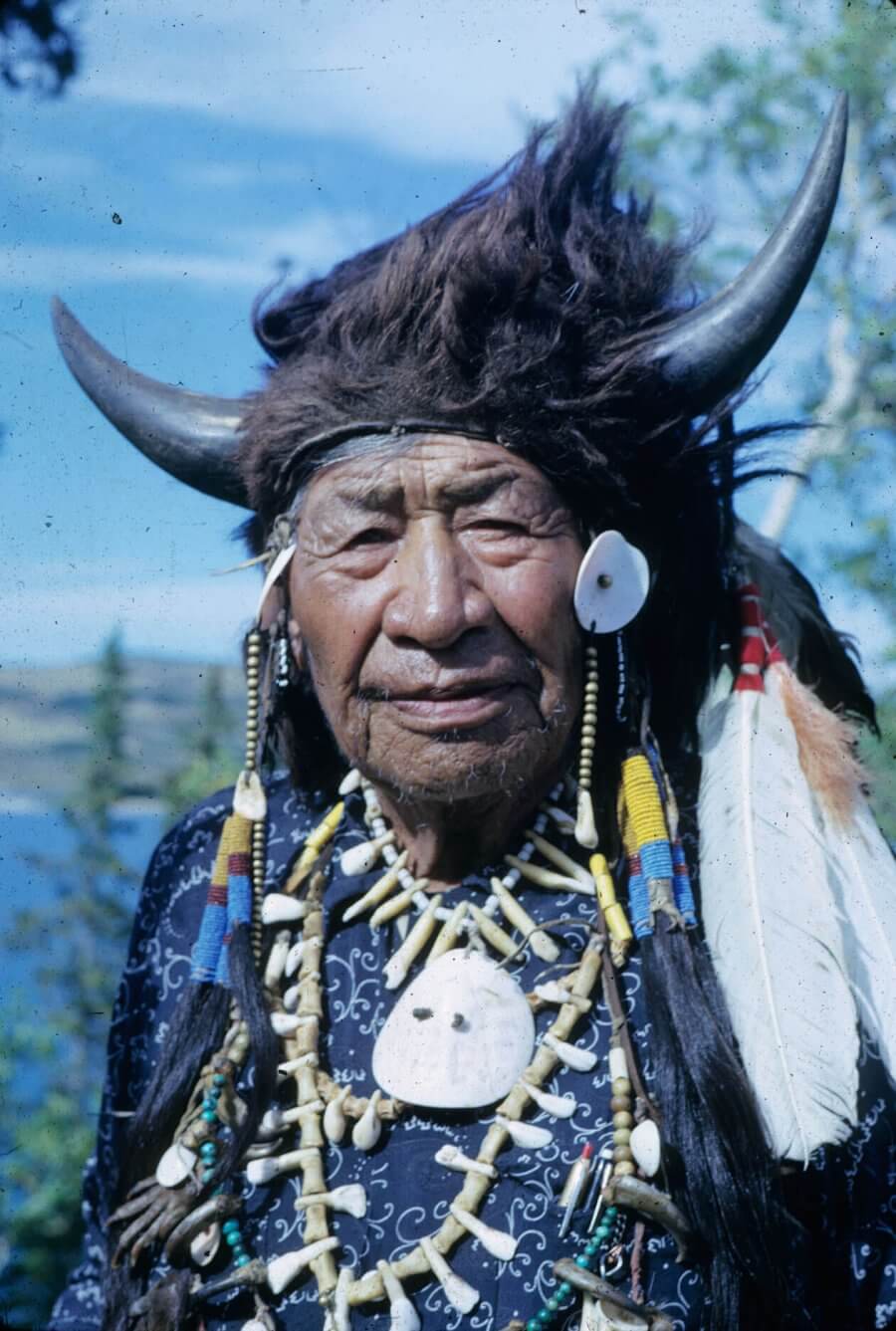

Three years ago, as an experiment, I began what has become the Indigenous Archival Photo Project. There are images of First Nations people, Métis people, and Inuit in the collections of historical societies, museums, and archives—often without any accompanying notes about the people who are in the photographs or the photographers who took them. I started sharing images on Twitter and Facebook in hopes of filling these gaps. As people recognized the subjects in the photographs and tried to identify dates and locations, sharing the images with their relatives in turn, the project gained its own momentum. It became an exercise in visual reclamation and digital repatriation of the photographs themselves—a return to community.

This particular set of photographs was taken in the 1950s and early 1960s by photojournalist Rosemary Gilliat Eaton, at a time when the daily lives of Indigenous peoples were largely invisible and of little interest to the settler population (settler is a term for non-Indigenous inhabitants of Canada). First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities faced multiple atrocities: Children were separated from their families and forced into foster care, adopted by non-Indigenous families, or sent into residential schools. The Indian Act stripped individuals of their rights, and the pass system (an informal process by which First Nations people who wanted to leave their reserves had to obtain written permission from a federal Indian agent) largely confined First Nations people to their communities. The government assigned Inuit dehumanizing numbered identification tags.

As a working female journalist, Eaton was a rarity in her time. She travelled much of Canada, east to west to north, propelled by her natural curiosity and on photo assignments. She sold her work to the National Film Board and to Weekend and The Beaver (now Canada’s History) magazines, among others. Eaton’s photos are distinct because of her ability to capture her subjects in a candid state—sometimes laughing, sometimes working, going about day-to-day things. Hers was, no question, an outside eye, but one with delicate sensitivity.

Indigenous and non-Indigenous viewers may see these photographs differently, but the images embody an inherent possibility of dialogue, exchange, and mutual appreciation and understanding. Eaton was taking her photos in often dark times, yet the images we see depict functioning, hard-working people and communities, reflecting the integrity of previous Indigenous generations. Her work is not framed within the “vanishing race” trope—depicting Indigenous peoples as romanticized (and thus dispensable) relics of the past—popularized by Edward S. Curtis, the American photographer famed for his images of Native American communities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. There is a resilient thread revealed in her photographs, fraying but not severed by colonialism. Eaton’s subjects are not victims.

© Rosemary Gilliat Eaton / Library and Archives Canada