The sun is setting over Bellevue Square in Toronto’s Kensington Market, shining through a storefront window on Augusta Avenue, bringing to life a tableau within. Twenty people sit at a long, narrow table in a long, narrow space, plucking bagels from a paper bag and dragging them through a tub of cream cheese. The cast of Sheila Heti’s play All Our Happy Days Are Stupid is gathered for a read-through, to prepare the show for runs in Toronto and New York. One of the co-directors, Erin Brubacher, makes an announcement. “Sheila couldn’t be here today,” she says. “She was afraid that if she came and heard it, she’d be tempted to rewrite the script.”

Heti has been rewriting the script for years—since long before her 2010 novel, How Should a Person Be?, thrust her into the literary spotlight, earning a “must read” recommendation from Lena Dunham and a 2,500-word review in The New Yorker by James Wood. At least, this is what we think we know about her life script from reading How Should a Person Be? The protagonist is, like her creator, a writer named Sheila who lives in Toronto and is deeply embedded in the arts scene. She spends time with her artist friends, some of whom share their names with Heti’s real-life friends. She has an ex-husband, as does the real-life Heti. She carries around a tape recorder to capture conversations with her friends, which she quotes verbatim. She struggles with a play that has been commissioned by a feminist theatre company. That play both is and isn’t All Our Happy Days Are Stupid, just as the Sheila character both is and isn’t Sheila Heti. It gets murky.

Murky seems to be how Heti likes it. When we meet, she is in no hurry to clear up which parts of the book came from her life and which didn’t. Inspired by reality TV shows, How Should a Person Be? offers the illusion of transparency, without providing transparency—much like Heti herself.

In addition to being a writer, Heti is the architect of a number of collaborative projects, including Trampoline Hall, a consistently sold-out monthly lecture series held at a bar in Toronto. She is working with artist Ted Mineo on a translation of the I Ching. After interviewing filmmaker Miranda July in 2011 for Bad Day magazine, Heti suggested that the two speak for an hour once a week on the phone. July later included Heti’s written correspondence in We Think Alone, a curated collection of emails.

Within the literary community, Heti is a polarizing figure, either heralded as a genius or dismissed as overrated. “Her greatest talent is convincing people she has talent,” one writer told me. “Mannered” is how a well-known journalist described her prose to me. “I just can’t read it. I can’t stand it,” another writer told me.

Over the course of her relatively short career, Heti has become a symbol of different things to different people: she’s the embodiment of a certain of-the-moment whimsical faddishness; a globally relevant artist who broke free of the usual Canadian constraints and never looked back; a feminist admirable for depicting women’s psyches honestly; and the cool kid who made of her charmed life a myth, and thus became someone to envy and emulate—or to envy and disdain.

Heti is thirty-eight and slight, with wistful blue eyes, lovely cheekbones, and a short-banged haircut that, along with her soft, slightly high voice, suggest something childlike about her. At the Tibetan restaurant where we meet, she offers me a sip of her butter tea before we begin chatting. She is sociable and gracious, but as much as she reveals herself in her fiction—or seems to—she is quick to note that there’s a part of her that won’t be exposed.

“That author Elena Ferrante,” she says, “I love that you can’t find out anything about her. Not to have to be out there as a person, there are things I like about it. I have a performative streak in me, so I’m not sure it would suit me entirely, but it seems ideal to just publish your books and nothing else.”

Heti grew up in the Cedarvale neighbourhood of Toronto, in a house decorated with Hungarian plates and her grandfather’s art. Her father, Gabriel Heti, was an electrical engineer, and her mother worked as a pathologist. Sheila “was often coming up with different and new ideas and projects,” according to her younger brother, David, a stand-up comic based in Montreal. “She didn’t seem afraid of much or of trying new things.”

In high school, she made a bunch of one-page feminist zines and taped them up in the halls; for this, she was called into the principal’s office. “I think in one of them I was naked,” she laughs. “I didn’t show my face, just my naked body. A friend teased me for it: ‘You were trying to say, Every body is acceptable, and you are this lithe sixteen-year-old girl.’ ”

At a Naomi Wolf lecture, she gave the zines to the author’s publicist from Random House of Canada, and subsequently, at seventeen, landed a contract to edit an anthology of teenage girls’ writing. The final product (“sexual abuse and sex and all the stuff people were writing about in their riot grrl zines”) was not to the publisher’s liking, however, and never went to print.

So began a lifetime of rejection from the mainstream, something Heti wears today as a badge of pride, as does her brother. “We are okay presenting ourselves as unsavoury characters,” he says. “We take a little bit of pleasure in that and don’t really give a shit what others think of our work.”

David, who has a law degree, was fired from a government job because of his stand-up material. “His stuff is so dark,” says Sheila. “We had family die in the Holocaust and he makes Holocaust jokes.”

Both siblings attribute this to their father’s influence. “My dad is very anti-establishment,” Sheila tells me. “He believes it’s good to make a fool of yourself; you shouldn’t worry what anyone thinks of you. My father would embarrass himself in public so that we would know it’s okay to be laughed at.”

After high school, she attended the National Theatre School in Montreal for a year. One of her projects, a play she wrote based on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust, was deemed inappropriate (the love interest was twelve) and the production was shut down just a week before rehearsals. She came back to Toronto without having graduated, and after a difficult, aimless couple of years began writing the work that would eventually form the kernel of her first book, The Middle Stories.

The stories were rejected by a number of Canadian literary journals. In 1999, she sent them off to author Dave Eggers, who had recently started McSweeney’s, a print magazine based in San Francisco that, in the late 1990s, swiftly and successfully forged a new literary aesthetic. “He wrote me to say, You’re a genius! I want to publish all your stories!” recalls Heti.

Ticknor, the interior monologue of a nineteenth-century historian carrying a pie to a dinner party, was her follow-up. Ben Lerner, the American author of 10:04, read it before any of her others. “Ticknor has a kind of Victorian prose, and How Should a Person Be? was much more an experiment in cinéma vérité or something,” he says. “I admired how radical the gap was between those two books—that she refused to repeat herself.”

Person was published to moderate acclaim in Canada in 2010. Two years later, it came out in the United States. Shortly after, the website Jezebel posted a small item titled “Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be? is blowing up,” which cited the New Yorker review and an essay in the Los Angeles Review of Books. Then came the Lena Dunham shout-out.

Like Dunham, Heti unabashedly mines her own life for material. In n+1 magazine, she published an alphabetized catalogue of sentences pulled from her diary. “Narcissistic” is a word that often comes up in conjunction with Heti’s name, as if she were a walking emblem of a generational deficiency. (“Grow up, Sheila Heti!” barked one Slate headline.)

Heti claims to read most of her reviews, but says she doesn’t take them personally. James Wood’s critique, for example, was mixed; he called her book “hideously narcissistic.” But Heti says it made her “giddy”—simply glad of the exposure.

“I don’t consider it mine,” she says of her work. “That’s a part that is shared with every human. I don’t want to say the collective unconscious, but it’s that idea. I don’t take it personally. That’s the soup that’s all of us.”

Her subsequent books include a non-fiction collection of musings, The Chairs Are Where the People Go, co-authored by friend and Trampoline Hall host Misha Glouberman, and a selection of essays and interviews called Women in Clothes, edited with Leanne Shapton and Heidi Julavits. She is now working on a book that considers the question of whether or not to have children. She has none.

Heti the artist can be hard to like because she doesn’t seem to need to be liked. Her fiction can be oblique (in Ticknor, the narrative voice alternates between first- and second-person without explanation) and surreal (The Middle Stories includes a kind of fable about a sentient dumpling), the prose written with a minimum of ornamentation. Her non-fiction, by contrast, is often collaborative, highly approachable, and democratic. She doesn’t seem to feel an allegiance to any particular style or audience.

“I have a lot of people around me who really judge everything they encounter, and I love having those people around me, but I’m not like that,” she says. To make art, “you look at art for how it inspires you, rather than looking at it from a moral perspective.” She loves self-help books (she has read eighty) and used to be obsessed with The Hills, a glossy reality show featuring “a group of young, superficial, rich, blond girls in Los Angeles and their dating lives that wasn’t about anything.”

When I told her I wasn’t sure how I felt about How Should a Person Be?, she replied, “I don’t think that’s the important question—whether you liked or disliked a work of art. Knowing what one thinks about it is overrated.”

Like so many of Heti’s projects, All Our Happy Days Are Stupid is a collaboration involving many of her friends and acquaintances. In 2013, it enjoyed a two-week sold-out run in the same Kensington Market space that is now being used for a run-through. “We would find people lined up out the door for tickets, which was a nice feeling,” says Erin Brubacher, who co-directed the play with Jordan Tannahill. “I mean, the space holds thirty people, but still.”

This February, All Our Happy Days Are Stupid—which owes more to Eugène Ionesco or Samuel Beckett than to George F. Walker or Ann-Marie MacDonald—is being remounted at the Harbourfront Centre World Stage in Toronto and at the Kitchen in New York (McSweeney’s is co-producing the US debut). The Kitchen is a venue known for experimental theatre, which is appropriate since Happy is not an easy work.

The storyline is clear enough: two families meet accidentally while on holiday in Paris, where one of the families loses its twelve-year-old son. However, the work strives for none of the verisimilitude of How Should a Person Be?, with its dialogue lifted from real life. Tannahill, who became the youngest-ever recipient of a Governor General’s Award for English-language drama last year, describes it as “self-consciously theatrical—absurdist.”

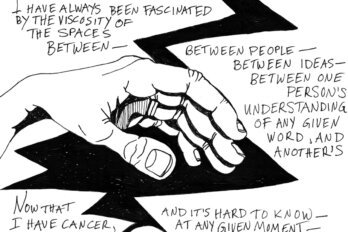

Overt self-referentiality, a kind of messiness that reveals the artist’s hand, runs through all of Heti’s work; it’s present even in the post-rehearsal discussion, where Brubacher and Tannahill are trying, with help from the cast, to hammer out staging details for the play’s remount.

“You lost me at neo-Brechtian,” says one actor to a gust of laughter. The cast is a deliberate combination of professionals and amateurs. In neo-Brechtian theatre, explains Tannahill, “the story and narrative is not supposed to disguise the artifice of the play.” Cast members will be visible to the audience even when they are offstage. Viewers will be made aware that what they’re seeing, in addition to the play, is “a group of friends coming together to put on a show.”

Of course, the transparency cannot be complete, since the actors know they’re being watched by an audience while they’re in the wings. But complete transparency is too much to ask of any person—even one who appears to truck in it. All writers are, in the end, something of a fiction to themselves.

This appeared in the March 2015 issue.