This story was included in our November 2023 issue, devoted to some of the best writing The Walrus has published. You’ll find the rest of our selections here.

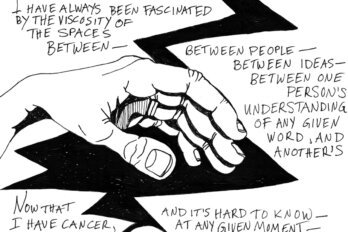

M. E. Rogan’s October 2016 cover story was our first feature ever on the struggle of trans and non-binary people. At the time, the community was under relentless attack in North America, with opponents framing trans people as sexual predators in order to bar them from using public bathrooms. It was hard to imagine the intolerance getting worse. But it did. In the United States, draconian new laws dedicated to eradicating “transgenderism” have made living as a trans person functionally impossible. In part, Rogan wanted to understand that hatred and the irrational fears that feed it. As someone who never fit into the binary gender model, Rogan examines the various arguments—scientific, cultural—that shape our understanding of dysphoria, and charts the lengths people will go to in order to feel at home in their bodies. The reporting ultimately became a journey of self-discovery for Rogan, with journalism becoming the tool by which they finally saw themselves. The story’s conclusion remains as devastating as ever.—Carmine Starnino, interim editor-in-chief, November 2023 issue

One day, not long after I turned five, I heard my brothers howling like wild dogs. They were taking turns hurling themselves off the top bunk bed. Their faces were on fire, and their hair was soaked with sweat. I stared longer than I wanted, but they didn’t notice me.

Over the next few years, I muscled my way in. Bloodying touch football, chicken fights, barefooted knife-throwing contests, one concussion. I pinned a poster of Walt Frazier to my bedroom wall, because I was going to be point guard for the New York Knicks. Then my brother Owen told me that could never happen, because I wasn’t a boy.

I didn’t believe him.

I butchered my long hair with my father’s toenail clippers and wore boy’s shorts under my Catholic-school uniform until I was caught during recess by one of the nuns. I begged my mother to buy me the same clothes as my brothers, but she insisted I wear dresses she made herself. She’d wake me in the middle of the night and have me stand on a kitchen chair. Then, turning me this way and that, she would make adjustments with sewing pins pressed between her lips like bullets.

I didn’t get my period until I was fifteen, and by then, I had become convinced it wouldn’t happen. Couldn’t happen. I was furious and helpless. I hung my head out the window and smoked a cigarette. Then I stared at myself in the mirror for a long time. I didn’t tell my mother I was menstruating. Every period I got for the next thirty-five years felt as if it had nothing to do with me.

I left my family home in Connecticut for university when I was seventeen. I came out as a lesbian at twenty, the same year I moved to Toronto, and became a mother at twenty-nine. By then, I had scrambled to higher ground, away from those early years, and found a livable compromise in feeling genderless. Eyes closed, I would try to imagine myself as male or female and was reassured every time I came up empty. Yet I couldn’t avoid misunderstandings. At my son’s elementary school, I was mistaken for his big brother more than once. I stayed away from public washrooms because it was painful when women stared, and I felt ashamed when I had to reassure people that I was in the right place.

As I got older, shame gave way to anger every time I was taken for a man. I told myself that other people lacked imagination and nuance. They were hostage to binary notions of gender and rigid expectations of what a woman should look like. But in this narrative, I never acknowledged my own relationship with my gender. Instead, I fought for as long as I could to stay on that higher ground.

In the mid ’90s, anxiety and depression almost pulled me underwater. I was hospitalized at Mount Sinai’s psychiatric unit. One day, I walked off and headed over to Kensington Market and into a Vietnamese barbershop and got my hair buzzed. In the twenty years since, I’ve never grown it back. I didn’t know it at the time, but that act was my lodestar. It gave people a way to see me, to acknowledge their insistent confusion, without my having to see myself.

From Caitlyn Jenner’s glamorous come-hither magazine photos to newly created summer camps for “gender variant” kids, the debate over what it means to be transgender has become part of our zeitgeist. At one end of the conversation are indefensibly regressive ideas that associate transgender people with deviance. Those in the business of sowing moral panic offer lurid descriptions of men in dresses lying in wait in public washrooms to molest little girls.

At the other end is the sympathetic reflex to affirm and celebrate—to insist, publicly at least, that we don’t need to understand why someone is transgender. Intuitively, each of us understands how vital it is to be accepted, and in turn, we want to show transgender people that we see them as they want to be seen.

Gender isn’t something most people think about critically. We don’t have to explain to each other what it feels like to be settled in this “male” or “female” experience of ourselves. We’ve already silently agreed on what those terms mean. A transgender person makes us re-examine this agreement. We’re thrown off balance when something as elemental as gender is questioned. Transgender people have the same abiding sense of self as every other human being, but when they put their essential selves into words and say, “I am transgender,” they are also saying, “This thing we agreed upon—it’s not the same for me.” Some are frightened by what they might hear in response.

We have tangled before, and will again, with equally fractious issues: race, class, religion, sexual orientation. But unlike gender, these others leave room for us to look away—we can’t or won’t see ourselves in that skin, in that neighbourhood, that bed. Gender is an unavoidable flashpoint, because many count on it as the basis for perceiving each other. Even in that kippah, that brown skin, that same-sex relationship, you have a gender, and I see it.

Too often, we hanker after simplicity: the public conversation many of us are having about gender is facile and oppressively careful. Some of this is in response to an earlier narrative that caused transgender people so much suffering. Until recently, psychiatrists rejected a biological basis for what was called gender-identity disorder—the distress associated with feeling out of sync with the sex one was assigned at birth. Instead, they offered treatments aimed at “curing” people by rooting out the psychological forces behind their presumed confusion. According to this approach, a surgical solution was reserved for only the most drastic cases.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a comprehensive list of psychiatric illnesses that helps clinicians make diagnoses. It was introduced in 1952 and has gone through four major revisions. In 2013, the DSM-5 replaced “gender identity disorder” with “gender dysphoria.” This new definition represents a sea change in how psychiatry understands transgender people. It shifts the focus away from seeing gender misalignment solely as a subjective problem and opens the door for a biological explanation. This has profound treatment implications. For someone who believes they have been born into the wrong gender, transitioning to their stated gender becomes a remedy, not a palliative treatment.

Where does gender identity come from? Current biological research focuses on fetal development. Normally, every fertilized egg has twenty-three pairs of chromosomes. If a fetus has an XY pair, it will become male—if it has an XX pair, female. Around six weeks into gestation, these chromosomes assert themselves, releasing hormones that lead to genital development and play a role in the differences between female and male brains.

That’s the typical scenario. Scientists, however, learn from exceptions and want to know whether atypical early fetal development might disrupt our relationship with gender. In addition to studying chromosomal variations, researchers are examining the myriad ways in which hormones, maternal biology, and the external environment affect fetal development.

As yet, there are no concrete answers as to why someone is transgender. What does feel concretized is an increasing social consensus, among progressives at least, that the science—the why of this—doesn’t matter. Or, more accurately, shouldn’t matter. For trans activists, any debate about gender dysphoria is suspect, even hateful.

A gender-questioning child is ground zero in any investigation of transgender issues. Gender variance in a young person is not like other challenges a parent might face. When a young boy tells his parents he likes boys, or a pubescent teen tells her parents that she’s a lesbian, nobody has to do anything. But as soon as a child identifies with a gender different from their natal sex, decisions need to be made. Hormone blockers? Social transition? Cross-sex hormones to prepare for transition? It’s a fast-paced game of double dutch, except it involves several ropes turning at once like an egg beater. The parent of a gender-questioning child has to jump in, weigh differing opinions and shifting social forces, and do something.

Some in the scientific community advocate against affirming a young child’s stated gender if they exhibit dysphoria. But many front-line physicians treat transgender kids with hormones and surgery because they believe that not affirming contributes to increased rates of suicide, addiction, self-harm, and homelessness. One survey of 3,700 Canadian teenagers revealed that 74 percent of trans students had experienced verbal harassment at school. Another survey, which looked at 433 trans youth in Ontario, found that 20 percent had been physically or sexually assaulted for being transgender—and that almost half had attempted suicide.

The DSM-5 defines gender dysphoria in children as “a marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender, of at least 6 months’ duration.” There are eight symptoms listed. To qualify for the diagnosis, a child needs to exhibit six of the eight symptoms, and the first is mandatory: “a strong desire to be of the other gender or an insistence that one is the other gender.”

The DSM didn’t have a category for gender misalignment in children until 1980. As a child in the late ’60s and early ’70s, I had seven out of the eight symptoms—including the first. Even without the language to name it, my mother was exquisitely attuned to my dysphoria, and it enraged her. We clashed bitterly, and often, about clothing, hair, how I walked, talked, played, and ate my food.

What would happen to someone like me today? How would a doctor, a different family, or the world see me?

How would I see myself?

It’s now assumed that being transgender is not something people choose, in much the same way most agree that homosexual people are “born this way.” This tagline helped gays and lesbians secure basic human rights such as job protection, access to spousal benefits, adoption, and marriage. It effectively stopped people from viewing gays and lesbians solely through a sexually voyeuristic lens—and we’re now seeing a similar destigmatization of transgender people.

One of the facilities in Canada that resisted a strictly biological explanation for gender dysphoria was the Child Youth and Family Gender Identity Clinic at Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). Ken Zucker, a psychologist, ran the clinic and also chaired the committee on gender dysphoria for the DSM-5. Over its four-decade-long history, the clinic assessed more than a thousand young people between the ages of three and eighteen—in recent years, the wait list for its services was a year long.

While Zucker and his staff always offered parents a range of options to explain and address their gender-questioning child’s symptoms, in many cases, parents were counselled to encourage their child to accept their natal sex—meaning, parents should not agree to pronoun changes or cross-dressing, or they should dissuade their child from playing with toys that didn’t match their natal sex. The clinic’s reluctance to immediately affirm a child’s stated gender was based on decades of clinical experience—backed up by the results of small sample studies from the Netherlands—that suggested that many younger children moved past their dysphoria without transitioning. When it came to older children, the developmental model used by the clinic was such that the majority were put on hormone blockers.

When a PhD student at the clinic did a follow-up study with 139 of Zucker’s former patients a few years ago, she found that 88 percent of them were now happy with their natal sex.* Eighty-eight percent is a stunning statistic—one that challenges the increasing trend toward affirming a child’s stated gender.

For years, trans activists had been vocal about their concerns that Zucker’s clinic was practising “conversion therapy”—a discredited pseudo therapy that attempts to change a person’s sexual orientation through psychoanalysis, aversion therapy, and, in more extreme cases, electric shock, lobotomies, or chemical castration. The DSM removed homosexuality from its list of ailments in 1973, but the term “conversion therapy” still packs an emotional wallop in the LGBT community.

Trans activists went to Rainbow Health Ontario (RHO) with their fears. An influential government-funded organization, RHO educates health care providers about LGBT issues and advises ministries on policy development. Zucker was shown the door in December 2015, the clinic was shut down, and trans activists celebrated.

It’s not clear what happened to the families on the clinic’s wait list. Many gender-dysphoria resources for children in Canada are grounded in philosophies diametrically opposed to those of Zucker. Some parents presumably sought out Zucker’s clinic in the hope that their gender-questioning child might be one of the many who end up resolving their dysphoria without transitioning.

As parents, we often say we want our kids to be happy. Or, if we’re trying to be more realistic, we hope for a balance of happiness and adversity: just enough to generate grit—not enough to break them down. But we can’t titrate the perfect dose, and transgender children will face levels of adversity well beyond what any parent can control. Does affirming a child’s stated gender ameliorate the inevitable adversity? The simple answer is yes. Studies show that youth who receive support from their parents are significantly less likely to attempt suicide.

But gender affirmation isn’t a panacea. For many transgender youth, their journey begins at a doctor’s office, and the relationships they form with medical professionals will last throughout their lifetime. There will be medications with known short-term side effects and unknown long-term side effects. Some transgender people choose surgery. Given the sobering statistics about dysfunction, despair, and victimization, it’s naive to think that parental affirmation alone can guarantee immunity from the anguish they reveal. Is it so unthinkable that a parent might hope their gender-questioning child will be part of the large majority of kids who resolve their gender dysphoria without transitioning?

“Let’s say it were possible to take a ten-year-old kid and make them either a well-adjusted lesbian or turn them into a female-to-male transsexual. I don’t see anything wrong with saying it’s better to make this kid into a lesbian, because being a lesbian doesn’t require breast amputation, the construction of a not-very-convincing false penis, and a lifetime of testosterone shots.”

So says Ray Blanchard, an adjunct professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto and a colleague and friend of Zucker. He worked at the Gender Identity Clinic at the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry in Toronto for fifteen years and then at CAMH from 1995 until 2010. He was part of the DSM-4 committee that set the diagnostic criteria for gender-identity disorder (before the name was changed to gender dysphoria). Unlike Zucker, Blanchard has never worked directly with children, but he is keenly interested in the transgender debate unfolding today.

Blanchard views some young trans males as butch lesbians who have capitulated to social pressures stemming from the media’s sensationalizing focus on transgender issues. According to him, the narrative of their transgender experience is a fiction fuelled by an emphasis on hormonal and surgical treatments.

He divides trans females into two categories: extremely feminine homosexual men and very masculine men who are sexually aroused by making themselves look and feel like women. In this formulation, both categories can manifest through gender dysphoria. Blanchard believes men in the first category are simply not masculine enough to succeed as men and will be more successful as women. He describes the second category as the result of an unusual sexual proclivity.

When Blanchard received a prestigious committee appointment to develop criteria for the DSM-5, the United States’ National LGBTQ Task Force sent a letter to the American Psychiatric Association protesting his involvement. For many in the LGBT community, he is the incarnation of the darkest beliefs that people have about trans people. Not surprisingly, the vitriol directed against him online is ferocious. In one post, he is accused of being a tortured Catholic, a closet homosexual, and a narcissist with an unwholesome attachment to his widowed mother.

One of Canada’s most visible trans activists, Nicki Ward, was exposed to Blanchard’s theories directly. Ward grew up in London, England, in the ’60s and remembers being punished for insisting on sitting on the girls’ side of the classroom. She tells me that after a few days of being parked in the hallway by herself, she’d learned her lesson: she should keep her mouth shut. “I felt like a girl, and everybody else was telling me differently, and it was nightmarish. It was utter isolation, because I feel something to be true at the soul level, and the world is telling me this soul level is wrong. So I prayed for God to change my body or change my mind.”

In her teens, she was assumed to be homosexual, a conclusion Ward tartly ascribes to the poverty of language. “There was no other word for somebody who was effeminate but didn’t want to have sex with boys. So I got beat up for being a fag, but didn’t get the fellowship of hanging around with gays. It’s that old joke—somebody drives into a tree, shoots through the windshield, and the police prosecute him for leaving the scene of an accident.”

In her twenties, Ward came to North America and threw herself into the straight world. She got married, had children, and held down a high-stress job in financial services. But she was also cross-dressing and fell into a pattern she calls “splurge and purge.” She’d buy women’s clothes and shoes and then throw them away in a moment of panic and shame. Ward’s marriage ended when her wife discovered the outfits stashed in the trunk of the car.

After they split up, Ward came out as transgender; the only way she could get access to her children was by persuading her ex-wife she was mentally fit. That meant attending CAMH’s Gender Identity Clinic, where, in the late ’90s, being transgender was still regarded as a psychiatric condition. Away from the clinic, she huddled with other transgender patients whose personal stories seemed to refute everything CAMH was telling them about their misalignment. In each other’s company, they could say, simply, that they were born this way and reject the notion that they were deviants.

“We used to go out after the CAMH group session on Wednesdays,” she remembers. “We knew we had to pay attention and to give speech to the clinic’s bullshit so that we could actually get access to health care, change our driver’s licence, and these things. Einstein Pub is across the road, and we used to go, around twenty trans, and talk. The real issues, the real healing, the real psychiatric work took place there.”

DEvita Singh, a former student of Zucker’s, is a clinical child psychologist based in London, Ontario. She authored the study detailing the 88 percent of Zucker’s patients who, in the language of the literature, have “desisted” in their gender dysphoria without transitioning.

Singh is frustrated that, despite the findings of her study and others like it, there’s now more pressure than ever for doctors and families to affirm a young child’s stated gender. She doesn’t recommend immediate affirmation and instead suggests an approach that involves neither affirming nor denying but starting with an exploration of how very young children are feeling. Affirmation, she argues, should be a last resort. Singh concedes that in cases involving older children approaching puberty, clinicians might need to move more quickly before the development of permanent secondary sex characteristics—broad shoulders, for example, or breasts—significantly increases the child’s distress. However, even with an older child, there is room for discussion if a slower approach is needed.

For her crucial study, described earlier, Singh approached 145 former patients between 2009 and 2010—all of whom had entered the clinic as boys who identified as girls—and asked whether they wanted to participate in her follow-up study: 139 agreed. When they’d originally consulted with Zucker at the Gender Identity Clinic, the youngest patient had been three and the oldest twelve. By the time Singh reached out to them to answer questions about their present-day lives, most of them were in their late teens to early twenties.

Of the 139 former patients in Singh’s study, 122—or 88 percent—had desisted in their gender dysphoria. They were now happy with their natal gender and living as males, with no desire to transition to female. The remaining seventeen patients had, in medical parlance, “persisted” in their gender dysphoria. Some were living as males but wanted to transition; some had begun to transition socially through informal name changes or more feminine clothing and hairstyles; and a few had legally changed their names to match their stated gender. Not one of the seventeen had pursued surgery.

After the survey, some of the participants who had desisted became intensely curious about what they had said to Zucker all those years ago. Singh went through their charts with them.

“Some sort of remembered that they really liked dolls or they wanted to play only with girls. Some didn’t remember that they liked those things or said that they wanted to be a girl. There were boys in there who had said, ‘I’m going to be a girl. I don’t want my penis.’ When I read them the extent of what they said at the time, they were quite surprised.”

Singh asked some follow-up questions, including: “Do you think your parents should have brought you to someone like Dr. Zucker?” “A fair amount of them said to me, ‘I can see why my parents did it, because they wouldn’t have known what else to do, but somehow in my mind, I knew this was something that was going to go away eventually.’”

Singh dismisses the claim made by many trans activists that asking questions about a child’s stated gender is transphobic or regressive. “A professional can’t be scared to ask important questions,” she says. “How could you presume to know how someone feels about themselves without asking them how they feel about themselves? The folks who are doing the activism work are not the desisters—they’re the persisters. Is there a way to appreciate that someone else with gender-identity confusion in childhood could have a different experience from yours? You’re seeing that child’s experience through the lens of an adult who has gone through various experiences for decades. And when you do that, you’re going to miss things that the child may be trying to communicate to you.”

I’m waiting for Andrew outside a coffee shop, and he’s late. Andrew is twenty-three, so that’s not unexpected. We’ve never met, but I spot him when he’s still half a block away. He’s wearing a navy peacoat over a pair of tight-fitting jeans that accentuate his curves. Later, he tells me he heard some nasty comments when he first came out as transgender, because he’s “pretty effeminate and very queer.” A couple of young trans males had mockingly accused him of “not even trying to look like a boy.”

There is something instantly likeable about Andrew. He’s a nimble thinker and hyper-articulate, but almost every sentence is followed by a short laugh. I can’t tell whether it’s a nervous tic or a form of punctuation, but it feels disconnected from the content of what he’s saying.

Andrew tells me that the dysphoria he felt before beginning his transition still lingers, but that it no longer dominates the way it did before. Early in his transition, he had bad days when he was frightened to go out in public because his voice wasn’t deep enough yet or he hadn’t bound his breasts.

Still, he can’t imagine himself as anything but transgender. And he sees his own experience of dysphoria as having played a crucial role in his development. “I would say it’s inextricably linked. Not that I can’t exist without dysphoria. Fingers crossed, I can exist without it eventually.” Andrew laughs. “But my politics have been so shaped by my trans experience. If I were a cisgender woman, I would not have had the exposure to all the things that define me as a person.”

Andrew left his family home in Orangeville, Ontario, the day after his last high-school exam. He headed out west, connected with a small trans community in Nanaimo, British Columbia, and started his transgender journey.

“I said I think maybe I’m bisexual, and my mom was like, ‘Okay.’ And then it was, maybe because I’m so afraid of getting pregnant, I’ll just be a lesbian. It was an actual terror, almost to the point of being a phobia.”

It takes me a second to grasp what he’s trying to convey: that this paralyzing fear of getting pregnant is what made Andrew consider he might be transgender. At nineteen, he began his social transition, but he didn’t tell his mother and father right away. He told his friends his gender identity and his new name. Then he came home to Ontario for a summer job.

If the first question a transgender person is asked when they come out is about hormones or surgery, we’re limiting the choices kids feel they can make.

“I was out to everybody except my parents, because I wasn’t sure how that was going to fly. I got outed by accident when one of my employers called my house and asked, ‘Is Andrew there?’ And my mom was like, ‘What?’ She wasn’t upset, exactly; she just wasn’t sure how to respond. She’s the kind of person who says, ‘My baby, you’re already perfect—why do you want to change?’”

Andrew navigated his transition, including the medical decisions, without his parents’ input. Back in BC, he found doctors who were sympathetic to his needs and who wouldn’t second-guess his decision to transition. He began receiving testosterone injections once every two weeks. Almost immediately, his voice got deeper, and he felt energized and hungry all the time. Andrew calls the initial effects of testosterone “tuberty,” because his moods were all over the map. He split the dose of testosterone in half and now injects himself with it once a week to smooth out the emotional highs and lows. He’ll do that for the rest of his life.

Last year, Andrew decided to have his uterus and ovaries removed, because his fear of getting pregnant had never completely gone away. And knowing that he still had female reproductive organs contributed to the sense of dysphoria.

He found a surgeon in BC who was well known in the trans community.

“My surgeon was awesome, this really nice guy who had done hysterectomies for pretty much all of the trans dudes in the area. We had the good fortune of having a doc who jumps through hoops for a living, so he was like, ‘Okay, to get this covered by insurance, we’ll say abnormal bleeding. If you’re a guy bleeding out of your junk, that’s abnormal bleeding.’ That was his workaround, and that worked really well for a lot of people.”

In the absence of a clear medical consensus, clinicians have to make their own decisions about how best to support a person with gender dysphoria. Andrew’s surgeon made a decision, as did Singh.

Joey Bonifacio is equally confident in the approach he pursues with young transgender patients. At thirty-seven, Bonifacio has a wheelbarrow full of diplomas, including an undergraduate degree in linguistics, an MA in anthropology, and a medical degree from UBC. He’s currently working on his master’s in theology. Over the course of a ninety-minute-long conversation before his evening clinic shift begins, he offers a wide-angle view of society’s evolving relationship with transgender people.

Bonifacio works at the Adolescent Medicine Clinic at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto and leads the Transgender Youth Clinic at SickKids hospital. He also sees patients at two centres for street-involved youth. He wears many hats and deals with some of the worst-case scenarios involving transgender kids.

From his perspective, it’s impossible to believe that a wait-and-see approach to gender dysphoria reflects a neutral stance. Not doing anything is still doing something. “I think the risk in taking the wait-and-see approach is low self-esteem and self-worth. Kids are really savvy, and they know what’s going on. They know what their parents are thinking about them. They’re not being validated, and that can have major effects on mental health. Then I see them for depression or anxiety or self-harm.”

In his relatively short career, Bonifacio has seen how language shifts have changed the conversation. The shift from “trans-sexual” to “transgender” made it possible for us to stop thinking primarily about vaginas and penises and start embracing a fuller appreciation of transgender people. It also opened the door for the word “cisgender,” which can be applied to the vast majority of people who are aligned with their natal sex.

Bonifacio believes that as our language evolves, so, too, should clinicians. Most family doctors now ask their teenage patients about their sexual orientation as a matter of course while taking down their histories. Bonifacio says doctors should also include questions about a patient’s gender identity. More critically, as the social consensus shifts toward affirming a person’s stated gender, doctors should as well.

But what does affirming involve? At conferences and media events about transgender youth, most of the questions Bonifacio is asked are about medications and surgeries. Despite all the post-modern deconstructing of language, he’s concerned that we’re putting everything back together through the same old binary lens. If the first question a transgender person is asked when they come out is about hormones or surgery, we’re limiting the choices kids feel they can make. What about the more ordinary questions we would ask other young people?

“You’re boxing this community into persons that need medications and need surgery,” Bonifacio says. “And you’re not taking into account the lived narratives of a diverse group.” There’s no shortage of internet videos showing trans kids taking their first testosterone shots. What happens if children absorb the message that there is only one way to be transgender? Only one way to be seen?

“They know the script. They’re supposed to say, ‘It started when I was three or four years old and got worse and worse. Then in my teenage years, that’s when I definitely knew.’ And my concern is if I don’t hear the real narrative, I get one that’s edited in order to meet the criteria to access care.”

Aconversation between a gender-questioning child and a parent can be a pas de deux of fear and anxiety. It’s brutally difficult for a child to come forward with their feelings and, sometimes, equally difficult for a parent to hear them.

Amanda Jetté Knox** lives in Ottawa with her spouse and three children. Two and a half years ago, her eleven-year-old came out as transgender.*** In a millennial twist, the news landed in Amanda’s inbox, direct from the kid in the next room.

“We got an email from our middle child, who was presenting as male and had a boy name and lived a boy life but had always been really unhappy. Always depressed and anxious, and we never really knew why. We hadn’t seen any obvious signs. There were no big declarations of ‘I’m a girl’ or ‘I’m in the wrong body.’”

Before the email, Knox and her spouse had been worried about Alexis for years. There had been lots of days when she had been so withdrawn she couldn’t go to school and wanted to hide in her bedroom all day. The family moved across the Ottawa River from Quebec to Ontario to access better care for Alexis, but nothing changed. “This is how far we had gone to try and figure out what was wrong with this kid and what was going on inside that little head. At her last birthday party, before she came out as a she, she came downstairs, opened gifts, and went right back upstairs. I could see that she was trying to be social, trying to be gracious, but just couldn’t do it.”

When Knox and her spouse got Alexis’s email, they went to her room and found her crying under the blankets. They crawled under with her, held her, and told her they loved her.

Then Knox went back to her own room and cried.

“It’s hard for any parent when something isn’t what they expected. It’s as simple as that. It doesn’t matter how open minded you are, and I would be lying if I said I didn’t cry. I cried into the eggs I was making. I cried while folding laundry. I cried in the car. I was grieving the life I thought my child was going to have. And all of a sudden, I realized this is a trans girl, a trans woman—and if you read the statistics, you know it’s a really tough road.”

But she also felt hopeful. After years of trying to understand her daughter’s unhappiness, there was finally something Knox could do to help. She never doubted that Alexis needed to be affirmed in her stated gender. She had friends in the LGBT community and was horrified when they claimed that Zucker’s clinic at CAMH (then still open) was championing a process that was tantamount to conversion therapy.

The day after she received her daughter’s email, Knox phoned the gender-identity clinic at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario and was told that the clock was already ticking. Almost immediately, doctors at the clinic put Alexis on hormone blockers.

“There are five stages to puberty,” Knox told me, referring to a common scale of physical development. “Tanner 1 through Tanner 5. By the time they’re in Tanner 2, gender-affirming doctors want to stop puberty, because changes are starting to happen to the body that are irreversible. If your child is saying, ‘No, no, I’m not a boy’ or ‘I’m not a girl,’ they want to get in there and stop it.”

At eleven, Alexis was in Tanner 3. She has been on hormone blockers for over two years now.

Eighteen months after her daughter came out, Knox’s spouse also declared herself transgender. Like Alexis, Zoe had always been unhappy for reasons Knox couldn’t understand. They had a good life with a healthy marriage, steady employment, and three great kids.

“There was always a little cloud hanging over her. Finally, for the umpteenth time, I tried to pull it out of her and randomly guessed, ‘What, are you a girl or something?’ And, yeah, that’s exactly what it was.”

Knox was floored. She and Zoe had met as teenagers and been together for twenty-two years. Knox was suddenly in a family photo that was drastically different from the one she’d carried in her head for years.

“We bought a home in the suburbs. We had kids, and they’ve been raised believing they have a mom and a dad. I imagined my life this way and lived it this way, only to find out it’s not that way. I no longer have a husband, and when people ask, ‘What does your husband do?’ I say, ‘My wife, actually, and she works in tech.’ I had to change. My identity changes; how my children are perceived changes. So we are all changing, and we are all transitioning.”

Lauren was just shy of her twentieth birthday when we spoke a few months ago—roughly the same age Andrew was when he began his transition four years ago. She had crushes on both girls and boys in middle school and identified as bisexual. In high school, she narrowed the field and came out as a lesbian. Lauren is bobbing around in the uniquely modern ocean of choices to describe herself. Recently, she’s wondered whether she is transgender.

We meet at a cafe near her home in Toronto. It’s packed at this early hour, but Lauren, who is tall and has striking red hair, is easy to spot when she comes through the door.

Lauren is both shy and forthcoming. Every sentence ends with the vocal tattoo of her generation, an upward inflection that makes each sentence sound like a question. But she is generous and remarkably unselfconscious when she speaks of her profound sense of uncertainty.

“I think it’s just a big question mark right now. I feel more masculine in a lot of ways but also definitely appreciate that I have the experience of living as a female. I used to think I was lesbian, but now that I’m realizing more things about my own gender, I realize I’m not necessarily attracted to one gender or another.”

In retrospect, she wonders whether identifying as a lesbian was an attempt to feel more masculine. Lauren admits it feels weird to say that now, because she’s aware of the stereotypes about mannish lesbians.

Plus, it didn’t work.

“Even though I had come out as a lesbian, people didn’t think of me as a butch lesbian, because I don’t act very butch, and at the time, I didn’t dress very butch either. Gradually, I dressed less femininely, but I still had long hair. When I cut all my hair off, it felt very nice. Now, I think, wow, I looked so awkward with long hair. It didn’t suit me at all.”

Cutting her hair helped with some of her uneasiness, but it wasn’t until she came across an article about a young, attractive trans male escort/porn star that she wondered whether her confusion had to do with her gender identity rather than her sexual orientation.

The shift was dramatic.

“Something resonated with me, because he’s really good looking, and he just seems so comfortable with himself. It made me think about my own discomfort with my body. I used to assume I didn’t like my body because I was overweight. But I don’t really enjoy having breasts. I don’t enjoy being curvy. And I didn’t realize that was why I felt uncomfortable.”

Lauren decided she should tell someone what she was feeling. She was about to leave for a six-month audio-engineering course in Winnipeg and worried about having to deal with these feelings on her own. She told some friends and her brother. Her parents drove her to Winnipeg: when they got there, she told them that she might be transgender.

“I told them because, honestly, I was a little scared—because, in a way, it did make things clearer, but it also confuses things more. I wasn’t worried about how they would react, because they’re such supportive people. My mom is pretty intuitive, and she told me she kind of had a feeling. I think that that may have been because the winter before, I was pretty depressed.”

In a new school in a new city, Lauren considered just jumping in with both feet and transitioning socially—beginning her life as a male around people who had never known her as a female. She even decided on a new name: Scotty. But she lost her nerve at the last minute.

I ask her where she goes from here.

“I’m still pretty confused. I feel strongly about one thing one day, and then I don’t. I keep telling myself I should really talk to someone, like a professional. I think that is the step I need to take to figure things out.”

Elly has experienced the staggering cost of not being affirmed in her gender for most of her life. In many ways, she is the sum of what Bonifacio fears for his young patients. She is also astonishingly resilient.

The two of us met while attending Alcoholics Anonymous about a decade ago and bonded over our shared impatience with all the God chatter. Her sadness stood out even amid the general AA gloom. It would be years before I heard her story.

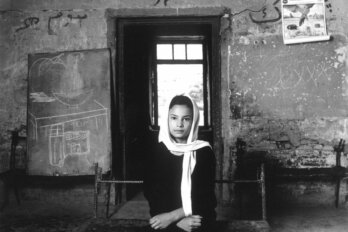

Elly was born in Iran in 1974, five years before the revolution. She told her mother when she was four that she wanted to live life as a girl. Her mother told her that wasn’t possible and suggested that perhaps she was just a different kind of boy. “I was a very effeminate child, and my dad put his foot down and said, ‘This has got to come to an end.’” He demanded that she stop playing with her sister’s Barbie dolls, but Elly continued to assert her femininity, and her persistence became a constant source of conflict. When Elly was eleven, her mother sent her to live with her grandmother in Belgium. A few years later, the family reunited when they immigrated to Canada and settled in Vancouver.

At fifteen, Elly decided transitioning would never be an option for her. “We were new immigrants to Canada. I had no means. I knew my parents would kick me out of the house. And I knew that kids like me lived on the street and that I would have to scrape by with prostitution. I knew it wasn’t going to be a long life, and it wasn’t going to be a good life.”

Eventually, she decided she had to try to live her life as a gay man. But around this time, puberty hijacked her androgynous looks. She felt as if she were disappearing, collapsing under the weight of her increasingly masculinized appearance.

She graduated from high school and enrolled at Simon Fraser University. The depression and anxiety caused by her gender dysphoria were crippling, and living with her parents was unbearable. Already, her drug and alcohol use was on the upswing. She quit university and, years later, moved to Ontario. In 2000, she found out she was HIV positive.

The next seven years were grim. “I was hopeless, and I was just waiting to die of HIV/AIDS. So I just did more booze, more drugs, more sex. My doctor said, ‘You’re going to die if you keep this up.’ I said, ‘I know, but I don’t want to live this life anymore.’ I was just getting more male with time, and I hated it, and I couldn’t do anything about it.”

After an overdose, Elly got sober in 2007. I have never seen anyone fight through so much trauma and grief, just to be seen. She began transitioning a few years ago and had genital-reconfiguration surgery this past January. We sat down together a few months later. She was at a low point, struggling with surgical pain, depression, and anxiety. Part of her post-op care required that she dilate her vagina four times a day to maintain the intended proportions.

Her surgeries have put her in debt—she’s sometimes terrified that because she made this decision so late in life, her transition will never be as successful as she needs it to be. She hates how deep her voice is, and she’s worried by her receding hairline.

“Recovery’s been hard.” Elly pauses and looks at me with a wry smile. “I feel like I’m the mayor of Paris looking at the city after World War II. It’s in ruins, and I’m not quite sure it’s going to take.”

Twenty years ago, I was walking down Shaw Street in Toronto and saw someone cycling toward me who looked familiar but different. It was only when he stopped his bike in front of me and smiled that I recognized him as a lesbian I used to know.

He’d begun his transition, and the effects of the testosterone were obvious. His voice was deeper, and he was leaner and more muscular. He seemed remarkably comfortable in his new skin and was in most other ways much as I remembered him.

Afterwards, I was flooded with anxiety. Over the next two decades, I replayed that chance meeting many times, and each time, I felt as if something were brushing against my leg in a dark lake. As transgender people became more visible, I became more uncomfortable, and my own narrative about why people mistook me for male began to buckle. When I dove into this essay, I was hoping to go below the surface and chase away whatever it was that had brushed up against me.

That’s not what happened.

When Singh revisited those 139 former patients from Zucker’s Gender Identity Clinic, she discovered that 122 of them had desisted in their gender dysphoria without transitioning. We don’t know why or how this occurred, but some believe the clinic’s non-affirming approach for young kids with gender dysphoria might have been a contributing factor.

What would have happened to those 122 if they had been affirmed at Bonifacio’s clinic instead? We can’t know. But implicit in our fascination with the question itself is the assumption that one outcome would be “better” than the other.

The seventeen other participants persisted in their gender dysphoria and today identify as transgender. We don’t know how or why this happened either, but we know they were not affirmed in their stated identities. It’s hard to imagine what that felt like.

But I know what it felt like. As a child, I met the full criteria for gender dysphoria and lived with a mother who was determined to extinguish this part of me. As a young adult, I met the DSM-5 criteria for gender dysphoria in adolescents and adults — I still do today.

We are driven inexorably to reveal ourselves. To be seen. It’s what we do, often imperfectly and against powerful forces. Despite my mother’s best efforts and, later, my own, I came to see what my mother had suspected fifty years ago.

In the writing of this essay, I now see me, and I identify as male.

Would my life have unfolded differently in another family or another era? Likely, yes. Would I have chosen hormone blockers during the worst of my pubescent years? Yes. Would I have transitioned? I can’t say. And I don’t need to know the answer to that. I am deeply attached to my rich and complex lived experience.

Here I am, today.

Where are those seventeen others?

* Since the publication of this piece in 2016, methodological flaws have been found in Singh’s study and other desistance research, and recent studies suggest that detransition rates are very low.

** Jetté Knox has since come out as a trans man and is known as Rowan Jetté Knox. He has given us permission to use his former name for this reprint.

*** Alexis now identifies as non-binary and not as a trans girl.