ARTS & CULTURE / JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2024

How Quebec Fell in Love with Documentary Theatre

Would you watch a play about hydro electricity? How about the dairy industry?

BY SANDRINE RASTELLO

Published 6:30, Dec. 4, 2023

On a Montreal stage one evening last May, Manuelle Légaré sat in silence as a recording of her father speaking to her and her sister played out over the speakers. Then she began her monologue.

“My father is talking to us about his coffee machine but I’m not really listening, even though I am missing out on the opportunity to learn how to make the best espressos in the world,” she told her audience, a panel of judges, theatre professionals, and friends and family. “Because in twenty minutes, my father is going to die.”

Légaré, one of six finalists in a documentary play pitching competition, had ten minutes to convince the jury that her idea, a play about medical assistance in dying, could become a hit.

She reflected on the closure her father’s assisted death failed to give her. She played audio clips featuring experts reflecting on the booming number of procedures in Quebec. She ended her pitch with one last joke from her father, celebrated Quebec comedian Pierre Légaré. And she went on to win the evening’s prize worth $10,000, which included support from Porte Parole, the theatre company organizing the event, to develop the show.

The endorsement was as good as it gets in Quebec’s vibrant documentary theatre scene. Sitting at the jury table was Porte Parole co-founder Annabel Soutar, who’s widely credited as a trailblazer for the genre in the province. Over the past two decades, her company has produced some twenty plays, on themes as diverse as health care, clean water, and genetically modified seeds, inspiring others to follow suit with their own range of topics and approaches.

Documentary theatre, like documentary film, investigates real events; practitioners look for compelling ways to adapt their findings to the stage, often re-enacting interviews verbatim or sharing their reporting struggles along the way. Hervé Guay, a scholar who co-edited a book about the genre’s recent bloom in Quebec, speaks of documentary theatres, in the plural, to reflect how local artists have put “fragments of the real,” such as interviews, artifacts, or witnesses, at the core of their work. He estimates that about one in four plays in the province now falls under that umbrella.

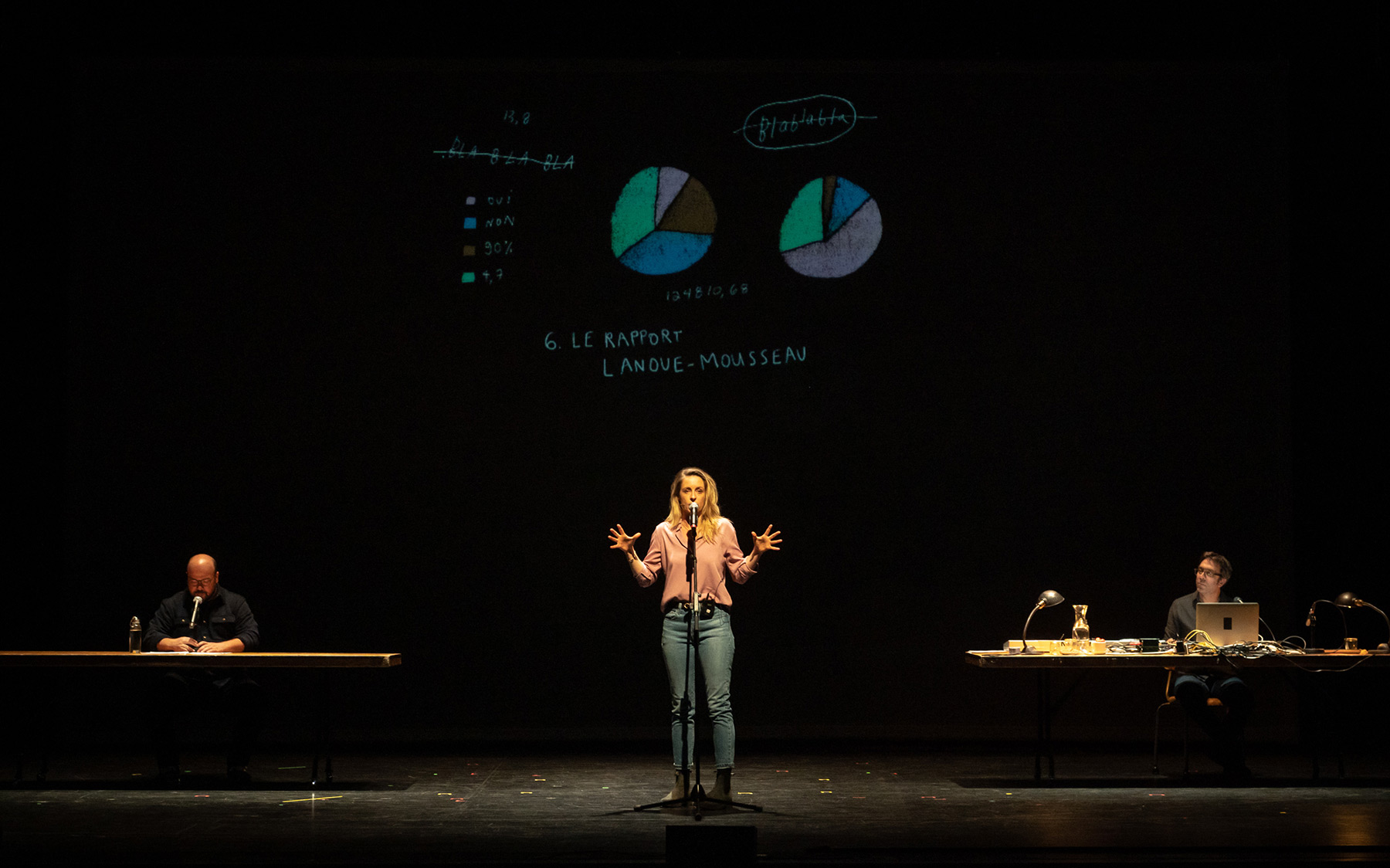

Sitting beside Soutar that night was her collaborator Christine Beaulieu, whose 2016 play J’aime Hydro (I Love Hydro) has been Porte Parole’s most resounding commercial success to date. The show was also my own introduction to documentary theatre, after a friend who could no longer attend gave me her ticket. At first, I was hard pressed to find reasons to sit through the three-and-a-half-hour deep dive into a seemingly dry topic—the relationship between Quebecers and power utility Hydro-Québec. But Beaulieu, a Quebec star in her own right, drew me in with her humour and honesty. At the start of the show, she plays the novice that she was at the beginning of her research and takes the public along as she becomes an expert on hydro electricity, pointing out the lack of transparency at the utility and questioning the need for big dams. It also helped me, an immigrant, understand how nationalizing electricity in the 1960s and doubling down on hydro power fit into a broader movement by the French-speaking majority to take control of its economy and modernize society. I looked at my power bill a little differently after that. So did many others, apparently; since it premiered, the play has had an audience of over 75,000 over the course of multiple tours, a TV broadcast, and a podcast.

Plays like J’aime Hydro can become a cultural phenomenon because of the special relationship francophone Quebecers have with theatre. Attending a show goes beyond entertainment: it is an act of support for their language and culture. Productions that bring societal questions and politically charged topics to the stage have found an audience in a province that rarely shies away from a good debate—least of all about its identity.

For Soutar, a main tenet of documentary theatre is attempting to answer a “burning” question with a full spectrum of viewpoints—including the most contentious ones. During a master class for Légaré and the other finalists last March, Soutar and Porte Parole co-founder Alex Ivanovici stressed the importance of seeking access to the story’s key voices and of overcoming one’s prejudices during interviews.

To them, this doesn’t mean controversial points of view shouldn’t be challenged, including on stage. But they should be represented. The ultimate goal is for the playwrights, actors, and audience to arrive at a deeper understanding of the issue and be better equipped to face a complex world.

“What is surprising?” Ivanovici asked. “When the conversation that you imagine as impossible is taking place.”

Real events have long served as inspiration for the stage. But documentary theatre wasn’t formalized until the 1920s, when playwright Erwin Piscator experimented with the genre to serve communist ideology in Germany, and later in Russia. As it spread around the world, it moved away from its openly propagandist roots and became an art form that tackles historical events and societal issues. Die Ermittlung (1965; The Investigation) by German playwright Peter Weiss has become a classic example of the genre. After attending the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, Weiss adapted the testimonies of some of the concentration camp’s survivors as well as SS personnel into a play, which opened simultaneously in several theatres in East and West Germany. In English Canada, documentary theatre rose to fame in the 1970s with The Farm Show, a play based on the six weeks a playwright and his actors spent in a rural community in Clinton, Ontario. But five decades on, the genre itself doesn’t have the same cultural cachet it currently enjoys in neighbouring Quebec.

Soutar was studying English and theatre at Princeton University in the early 1990s when she learned of the work of actress and playwright Anna Deavere Smith. For her play Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992, Deavere Smith interviewed more than 300 people to gather various perspectives on the riots that rocked the city after the acquittal of the four police officers who had brutally beaten Rodney King. She selected and embodied some forty of them, alone, on stage.

In Deavere Smith’s approach to probing a charged topic, Soutar saw an opportunity to combine her interests in politics, journalism, and theatre. “I have always found pleasure in sitting around a dinner table where everybody doesn’t agree but remains at the table,” she told Radio-Canada in a 2020 interview.

As a playwright, Soutar, who grew up in an English-speaking household in Montreal, sensed documentary theatre could be that table for Quebec. It was a pivotal time for the province, which was grappling with the aftermath of the 1995 referendum; Soutar felt that being local but anglophone gave her enough distance to deliver a fresh perspective on the issues of the day.

Determined to work in French, she joined forces with Ivanovici, whom she had hired for a play (he later became her husband). For the first project they partnered on, they travelled across the province during the 1998 election campaign, stopping in snack bars, churches, and grocery stores to capture the mood of Quebecers. The resulting production, Novembre, offered a snapshot of Quebec society and was performed in Montreal by some fifteen actors speaking in both French and English—without subtitles. Press coverage of the play was largely positive, Soutar recalls. In 2000, she and Ivanovici launched Porte Parole.

Also instrumental in raising the genre’s profile in Quebec was Rwanda 94, a play by the Belgian collective Groupov, says Guay, the director of the literature and social communications department at Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières. It appeared at the 2001 Festival TransAmériques in Montreal. A poetic and powerful show about the Rwandan genocide that incorporated material such as eyewitness accounts, television images, and odes and chants, Rwanda 94 demonstrated the full potential of that art form, he says.

Guay believes documentary theatre has thrived in Quebec because artists have experimented with various aesthetics, straying from a purely realistic approach. For Pas perdus: documentaires scéniques (2022), which explores transmission, solace, and joy in Quebec step dancing, Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette and Émile Proulx-Cloutier put non-actors, who perform some tasks in silence while a recording of their voice plays on speakers, on stage. In Alexandre Fecteau’s Hôtel-Dieu (2018), about suffering and grief, spectators are invited to join in therapeutic rituals.

One hallmark of Quebec documentary theatre, says Guay, is that behind-the-scenes moments often become part of the show. In J’aime Hydro, Beaulieu re-enacts her worst bouts of self-doubt. In Run de lait (2022; Milk Run)—which dives into the disappearance of small Quebec farms, farmers’ mental health, and the byzantine system of milk quotas—playwright Justin Laramée shares the headaches of trying to get access to Saputo and other big players in the dairy industry. (Laramée co-produced the show with a Quebec theatre.) He enrolls his whole family to help explain the maze of official milk categories. In one scene, Laramée plays a truck driver speaking with a customs agent played by his own son, whose recorded voice is projected from speakers. Their exchange demonstrates how dairy producers circumvent some of the restrictions of Canada’s supply management system.

Documentary plays tend to draw crowds that don’t often go to the theatre, according to Guay. This is especially true of Run de lait: farmers were in the audience for a performance I saw in Drummondville in March, and several of them stayed on for a discussion afterward. Mélissa Duplessis, an expert in dairy cow health and nutrition, attended with her father, a former dairy producer. “He liked it. Sometimes, during the play, he commented out loud,” she recalled. “People live more and more in cities; they don’t understand the reality of what happens in the country. It’s good, at times, to bring the two realities closer.”

Some critics, however, have questioned whose realities get represented on stage. In 2016, Soutar produced Fredy, a play she wrote that investigates the 2008 police shooting of Fredy Villanueva, a teenage Honduran refugee, in Montreal. Though Villanueva’s mother and members of the family’s support committee originally agreed to having Fredy’s story represented, they later withdrew their consent. Ricardo Lamour, one of the actors and a member of the family’s support committee, expressed concerns that Villanueva’s story had been appropriated and that the play depoliticized the killing and humanized the police by including their testimony. At first, Soutar incorporated his objections into the play. But Lamour and some other cast members eventually withdrew from the production when they learned that Porte Parole planned to continue and tour the show despite the family’s objections. A petition circulated recommending that the show be shut down, until Soutar listened to the family’s demands and Fredy’s mother authorized the production. The petition’s authors pointed out that Soutar had written a play about a community she wasn’t part of and hadn’t given enough weight to its members’ input.

In a Facebook post responding to the criticism, Soutar wrote that the value of her play was in presenting audiences with diverse perspectives and in offering them a space to reflect, including with post-show discussions. Ultimately, the controversy raised the broader issue of who can, and who should, tell certain stories.

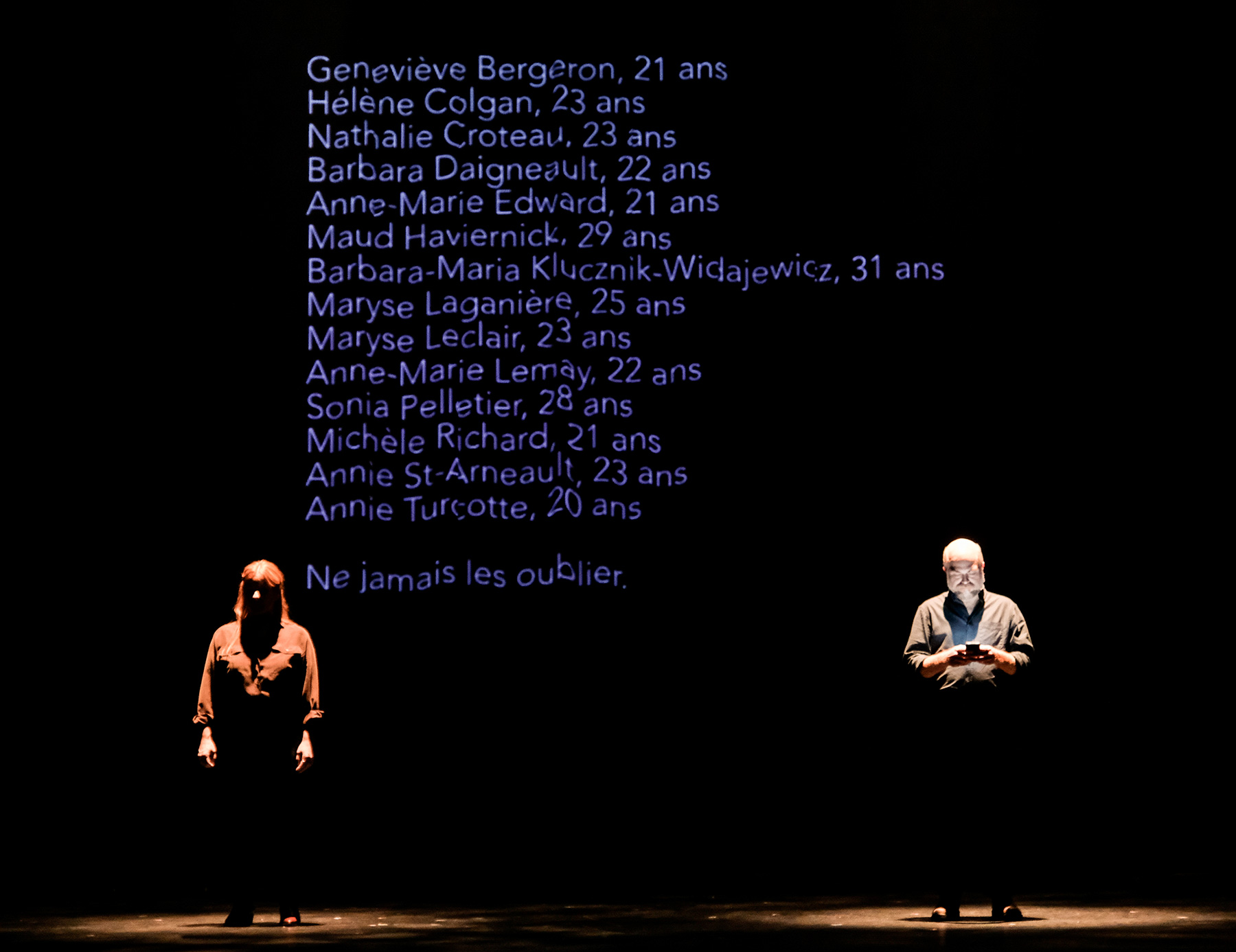

Project polytechnique, Porte Parole’s latest play, revisits the December 6, 1989, massacre of fourteen women at the Montreal engineering school. It follows Jean-Marc Dalphond, who lost his cousin Anne-Marie Edward that day, and co-author Marie-Joanne Boucher as they contend with the weight of their memories. What can be done, they ask, to prevent more mass shootings?

The play, which premiered in November, incorporates interviews with a survivor of the shooting, cyberviolence and masculinism experts, gun enthusiasts, and a police officer who entered École Polytechnique after the shooting, among others. But there was one voice that Dalphond deliberately wanted to leave out. The Polytechnique killer had targeted the women because of their gender. As part of Dalphond’s research for the show, he’d gone undercover to infiltrate misogynist forums online, buying a dedicated phone and creating a fake profile so he could navigate blogs and discussions of self-described incels—typically heterosexual men who believe women are denying them sex and whose resentment tends toward violence. Dalphond was haunted by his descent into an underworld where men like his cousin’s killer are glorified. He didn’t want to make any direct contact—not even for the show.

But from the beginning, Soutar made it clear there would be no story without attempting to understand where that hatred came from. “We’re not here to get up on a moral soapbox and tell people they’re bad,” Soutar says. “People do that all the time on Facebook. There’s no narrative muscle in that.”

Boucher and Ivanovici agreed with Soutar, and Dalphond eventually relented. He commented on a post in an incel forum, which led to an online exchange with a young man. After learning he was a teenager, Dalphond felt a responsibility to try to help him understand the toxicity of the incel movement and revealed that someone he knew had been one of the Polytechnique victims. Soon after, Dalphond was barred from the site. Dalphond and Boucher also met with the author of an anti-feminist blog who was later sentenced to jail time for promoting hatred against women.

Some theatre lovers in my entourage told me they were reluctant to see Projet Polytechnique because the topic is too dark, too close to home. I can see why. When I attended a table read of the script with the cast and crew, in April, there was a gravitas in the room that lingered with me long afterward. Dalphond told me music and singing would help bring some light to the play’s darkness. But there’s no escaping his emotional journey or Boucher’s traumatic childhood memories, the stern warnings of an incel expert about the risks of infiltrating that community, or the bitterness of a seventeen-year-old growing up in the dark corners of the web.

Dalphond is still not convinced that engaging with incels was useful, but he has come to terms with the experience. “The stance I took is that I give them space so that, collectively, we get our head out of the sand, look at reality, and say, ‘We need to act,’” he says.

But his hesitation reflects how, in an increasingly polarized society, it’s hard to make a case for bothsidesism—the credence, often invoked in journalism, that all perspectives on an issue must be included for the representation to be considered balanced. Is it still worth rounding up diverse voices, even for a play, at a time when extreme views are becoming normalized?

Jenn Stephenson, a professor at the Dan School of Drama and Music at Queen’s University, is not sure. While documentary theatre of the 1990s openly recognized that it was impossible to find the truth, she says, there was still something idealistic to Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 or The Laramie Project, an American play that portrays a town in the aftermath of a hate crime.

“The idea was to educate people about racism, to educate people about homophobia, and to show people that if we all listen to each other, we will understand each other,” she says. “Thirty years later, we’ve discovered that’s not possible.” As a society, we’ve become more disillusioned, she adds. “I think we’ve changed our ideas about truth.”

That’s not how Soutar sees it. After Projet Polytechnique, Porte Parole is planning its next instalment of The Assembly, a show it’s put on in several countries to encourage a discussion between people with clashing views. (The next production will focus on energy transition in Canada.) The pitching competition, launched last year, is Soutar’s attempt to support emerging voices in the genre. Like Légaré, the other finalists followed Porte Parole’s tradition of pitching plays about sensitive subjects, including a controversial Club Med resort and pro-suicide online communities. A non-binary trans artist’s show about queer representation in Quebec in relation to the AIDS epidemic won the competition’s people’s choice award. There were fifty-eight applicants in all, a sign of Quebec’s healthy appetite for documentary theatre and all the burning questions it tackles.

For Soutar, the genre can help the audience get some clarity in overwhelming times. “Is that educating? I don’t know,” she says. “Because oftentimes, at the end of my plays, there are more questions than there are answers.”

Correction, January 11, 2024: An earlier version of this article stated that Rodney King was killed by police in 1991. In fact, he survived the assault and died in 2012 of unrelated causes. The Walrus regrets the error.