On December 6, 1949, a government official named Kingsley Kay signed a confidential memo. Kay worked at the Department of National Health and Welfare, and he had just completed an inspection of Yellowknife’s two young gold mines, Con and Giant.

His ten-page report detailed how the industrial roasting process that separated gold from rock had created a dangerous by-product: arsenic trioxide, a colourless, odourless powder known for centuries as a poison. Though the roasting at both mines was similar, each handled the toxic results differently. Located on the southern edge of Yellowknife, Con Mine attempted to contain the arsenic by dumping it into a small lake. Giant Mine, from its waterfront location a few kilometres north of the city, blew the arsenic out a tall smokestack, hoping to disperse it through the air.

Neither method seemed ideal. Kay noted that six cows had died of arsenic exposure near Con that spring and that widespread poisoning of horses, dogs, and wild animals had been observed in the area. Kay also remarked that, in January 1949, soon after Giant started roasting, “the first human case of poisoning reached hospital.” Kay concluded that mining should not continue until both companies installed equipment to prevent further environmental pollution. “Roasting,” he wrote, “should be stopped.”

But it wasn’t. Together, the mines operated for more than half a century before going cold. At Giant, engineers installed increasingly effective mechanisms to prevent the escape of the toxic dust into the air: emissions dropped from roughly 7,300 kilograms per day in 1949 to 3,000 in 1957 and eventually down to only one or two dozen kilograms in the last years of the operation. Still, roasting went on until the mine went bankrupt, in 1999. Con, which had continued to experiment with dumping the arsenic into water, closed four years afterward, in 2003. Privately owned, it hasn’t drawn much public attention. (The lakes in its immediate vicinity, including Kam Lake and Frame Lake, remain a no-go zone for swimming.) Giant, however, was harder to ignore. For years, its officials collected arsenic dust that had blown out the mine’s smokestack, free to drift on the wind before settling back to earth, and buried it underground in unused chambers called stopes. It’s still there today: 237,000 tonnes of a powder so deadly that it takes less than a teaspoon to kill a human.

The Yellowknives Dene First Nation has borne the brunt of that danger. One of its two main communities, N’dilo, lies directly across a small bay from where Giant’s smokestack stood for decades. The present-day city of Yellowknife has been part of the First Nation’s home territory for more than 7,000 years. This is Canadian Shield country: a wide-open Tom Thomson landscape of wind-gnarled conifers and ancient, eroded rocks dividing lake after lake. Yellowknife Bay, before the onset of colonial settlement and mining, lay on a caribou migration route, and moose abounded too. The area was known for its berries and plants and for fish, which bounced through the rocks of a clear creek before pouring into what’s now called Back Bay. It had, according to Yellowknives Dene chief Fred Sangris, “everything we need.” But then it was occupied and mined, and the flora and fauna were poisoned or driven away. What was once Giant is now a fenced-off toxic waste site and a permanent threat. The Yellowknives Dene have never been compensated for the 7 million ounces of gold their land yielded—or for the wreckage left behind.

Last year, seventy-one years after the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs overruled Kay’s call to stop the roasting, federal representatives began negotiations with the First Nation on reparations and an official apology. Someday soon, Canadians may see a prime minister rise in the House of Commons and solemnly express remorse for what happened at Giant. But, with so much damage already done and the threat of further catastrophe still lying under the ground, it’s hard to have much faith in what an apology might achieve.

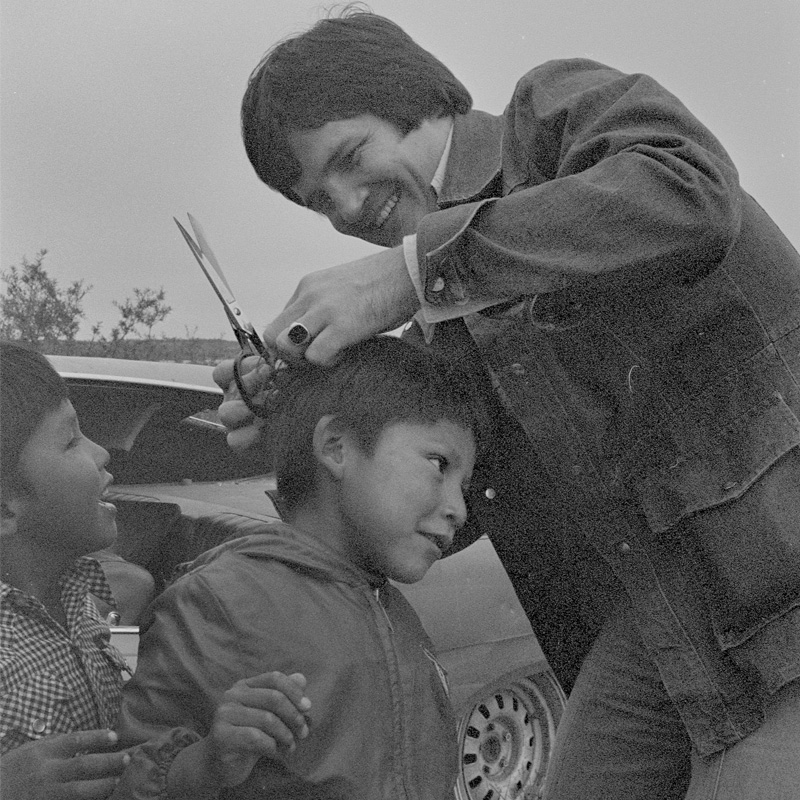

Sangris, now sixty-four, was a child during Giant’s early years. He remembers crossing the mine property by dogsled, first with his father and grandfather, as they travelled to and from their traplines, and later with his friends. “Nobody told us there was something wrong with that land over there,” he says. The government ran ads in the Yellowknife newspaper warning about the arsenic throughout the 1950s, but the ads appeared in English only; few if any Yellowknives Dene would have seen or been able to read them at the time. Sangris remembers collecting firewood from the mine area and watching it burn blue and green. Or crossing streams of open wastewater with his dogs and, in the days afterward, seeing the animals lose the fur on their paws and legs, the bald skin breaking out with sores. Some of the animals went blind, he recalls. Some of the community’s sled dogs died.

The Yellowknives Dene also recall several suspicious human deaths during this period. Government documents focus on just one: a Dene toddler in the spring of 1951. His death was blamed on the high level of arsenic in the fresh snowmelt (a primary water source for the people in N’dilo), and the incident pushed officials at Giant to finally implement the first attempted pollution controls at the roaster. The boy’s family was paid $750 in compensation.

Arn Keeling and John Sandlos are the co-authors of Mining Country, a new history of the industry in Canada. They point out that mine officials didn’t feel pressure to do anything other than let the emissions rip. “The bigger picture is that of regulatory failure,” says Keeling. There was no cap set for the emissions, and the pollution reductions were done voluntarily, at a pace and cost set by the company. The mine did what corporations do: extract profit while minimizing costs. The federal government did nothing to rein it in.

Sangris agrees with the two historians. “The golden goose was laying golden eggs here, and they didn’t want to kill it,” he says. “All fingers are on the federal government. We don’t blame the workers. We don’t blame any people who were employed here.” He was answering a question I hadn’t yet brought myself to ask directly: Was my family partly responsible for the harm done at Giant Mine?

Bob Tait, my grandfather, moved to Yellowknife in the spring of 1950, along with my grandmother and my aunt, then just one year old. He was the product of a comfortably upper-middle-class Vancouver family, a Royal Canadian Air Force veteran who’d left half a lung behind in Europe when the war ended but still held a lit cigarette in virtually every photo I’ve ever seen of him. He started work at Giant Mine on May 15, as a testing engineer. By the time my mother was born, in late 1954, he had been promoted to metallurgist. In 1956, he was promoted again, becoming the superintendent of the mill, the above-ground facility where ore is processed after the miners carve it out of the earth. That meant the roaster fell directly under his purview. He was still in that role in 1958, when his team installed a baghouse—a tool that separated arsenic dust from air and allowed the mine to recapture a greater share of the toxin before it escaped the smokestack.

Not all gold mines produce arsenic pollution the way Giant did—that’s a function of the particular type of rock in the area. Yellowknife sits on a volcanic belt called greenstone, rich in a mineral called arsenopyrite. It’s this ore that holds the gold, but arsenopyrite doesn’t release it as easily as some other materials do. Many mines extract their gold through a cyanide leaching process. At Giant, it needed to be roasted out—a process that turned the naturally occurring arsenic in arsenopyrite into a dust that could float on the wind and sink into water and soil. In a 1961 technical paper outlining various changes to the processes at the mine, my grandfather wrote that the baghouse proved “a very satisfactory unit” and praised the way “the entire plant revision was carried out at very modest cost.”

My family lived out at the mine’s employee settlement, a few kilometres from town. The community seemed cozy: there was a curling rink, a fire hall, a commissary, and a recreation hall with a gymnasium, a theatre, a library, pool tables, and a snack bar. When he wasn’t working, my grandfather curled, golfed, and volunteered. He was, for a time, the president of the Home and School Association, and he served on the board of the Yellowknife Hospital Society. My grandmother, Janet, sang in the annual variety show, and my aunts enrolled in Brownies, figure skating, and swimming lessons. Soon after they left Yellowknife in the summer of 1961, my grandmother died of colon cancer. Less than a decade later, my grandfather followed her, dying of an aortic aneurysm after a series of heart attacks. Orphaned before she turned twenty, my mom remembered Giant dimly as a rocky, snowy playground where the miners’ kids ran loose above the lake. She’s gone now too, killed by a stroke, so I can’t ask her how much she or her parents knew about the arsenic during the years when the family lived in its shadow.

Keeling and Sandlos offer some context. “It’s not like arsenic was some new synthetic chemical that hadn’t been tested,” Sandlos says. “Everybody knew arsenic was dangerous.” But, in the 1950s, he and Keeling point out, the government’s English-language ad campaigns put the emphasis on transmission by water rather than by air. So long as they didn’t drink the contaminated water, Yellowknife’s settler community had no reason to believe it was at greater risk than any other midcentury industrial town. It even managed a sense of humour about the situation: at one point, the town staged the Broadway murder-comedy Arsenic and Old Lace.

It wasn’t until the late 1960s and early 1970s that wider public awareness about environmental pollution began to stir. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring had galvanized a movement after its publication in 1962, and on another front, governments were beginning to require cancer warning labels on products like cigarettes. By then, many of the worst years of active arsenic deposition at Giant had passed, though the mine was still expelling anywhere from 100 to 400 kilograms of arsenic trioxide per day. But few knew for sure what the health implications of the emissions—at either the high volumes of the past or the ongoing lower rates—might be.

Arsenic can trigger vomiting, diarrhea, cramping, numbness, and in severe cases of acute poisoning, death. Today, we know that chronic exposure is also linked to various cancers (bladder, kidney, liver, lung, and skin, to start with), diabetes, and heart disease. Back then, the science was murkier, but concern about the potential health risks was rising. As that concern grew, a series of competing public health reports attempted to grapple with the scale of the problem. The United Steelworkers of America, representing the workers at Giant, partnered with the National Indian Brotherhood on one study, since the Yellowknives Dene and the mine’s labourers were the populations most at risk. The newspaper ran headlines that ranged from semi-reassuring to ambivalent, including “Most of YK safe from arsenic” and “Yet another arsenic report.”

It can be hard to recall—awash as we are in knowledge about the carcinogenic properties of everything from our BPA-laden water bottles to the asbestos in our attics—the extent to which the environmental component of disease was once a mystery. My aunt Rosemary remembers her parents telling her not to eat the snow at Giant, or the berries, and not to swallow the lake water when she swam. (Of course, “we did eat the snow, and we did eat the berries,” says my aunt Shelagh, the eldest sister.) But it wasn’t until the 1980s, working in the labour movement and as an advocate for worker health and safety, that Rosemary began to seriously wonder about a link between her mother’s death from cancer and their arsenic-dusted life at Giant.

Today, the Northwest Territories government maintains guidelines and colour-coded maps for safe use of the landscape around Yellowknife. In some areas, swimming and fishing are deemed safe; in others, residents and visitors are still warned against drinking the water, fishing, swimming, or eating any nearby fungi or plants. A toxicologist from the University of Ottawa leads a program that monitors arsenic levels in the region. What’s unknowable is the scale of the harm done before anyone in government was paying attention. It’s almost impossible to definitively link individual cases of complex diseases, like cancer or stroke, to a single clear cause or exposure; it’s impossible to say exactly why my grandmother, who spent much of her adult life in mining towns, died at forty-five while her sister, in Vancouver, lived to be ninety-three. Epidemiologists can only tease out patterns and influences in large data sets. And that kind of community-wide data can’t be produced retroactively.

Did my grandfather wonder whether his work had harmed his family? Shelagh and Rosemary don’t remember him ever hinting at that kind of doubt, though he wasn’t always a man who shared his feelings, and he became even less so in his later years. I do know that he was proud of his work, and maybe on some level he was right to be: under his leadership, from 1956 to 1961, Giant’s emissions dropped from roughly 2,700 kilograms of arsenic trioxide per day to 150. But he was still, formally, the supervisor of the mine’s dangerous pollution.

Whether he helped or hurt or both, I’m left with the stubborn fact that five members of my family lived at Giant during some of its most toxic years, and only two survived past the age of sixty. On a much larger scale, the Yellowknives Dene are left to wonder exactly how much harm was done to them. How many lives shortened, how many cancerous cells metastasized, how many heart walls weakened? And what does a federal process of redress and remorse mean for a country attempting reconciliation? In the ugly tangle of colonization, Giant Mine is just one thread.

Aerial view of Giant Mine (1954). (NWT Archives / Henry Busse / N-1979-052-4305)

The first white traders and explorers came to the southern side of Great Slave Lake in the 1770s, seeking fur and minerals, and by the 1790s, they had reached the Yellowknife area. Throughout the nineteenth century, the Hudson’s Bay Company extended its reach—many of the communities in the Northwest Territories are still named for the company’s trading forts. As late as 1904, an inspector of the North West Mounted Police declared that the area “will in all probability be nothing but a fur-bearing country.”

Treaty 11, the last of the numbered treaties, was signed in 1921. It covered much of the present-day Northwest Territories as well as pockets of the Yukon and what is now Nunavut. The text of the treaty read, in part, “The said Indians do hereby cede, release, surrender, and yield up to the Government of the Dominion of Canada, for His Majesty the King and his successors forever, all their rights, titles, and all privileges whatsoever to the lands included.” But the text was not properly translated and shared with the local chiefs—who believed they’d signed a peace and friendship treaty rather than a land cession—until 1969. “It was shocking,” Dene national chief Norman Yakeleya told the CBC of the eventual reveal. Dozens of witnesses to the original treaty signings had also signed affidavits regarding the verbal promises that were made alongside the untranslated text. Those promises included a vow to the signatory First Nations “that nothing would be done or allowed to interfere with their way of making a living as they were accustomed to and as their antecedents had done.”

By the 1930s, Yellowknife was a gold rush town. The claims that would become Giant Mine were staked in 1935, but the Second World War put a damper on development. The mine went into production in 1948. On June 3 of that year, workers at Giant poured its first gold brick. When the mine’s American ownership declared bankruptcy and walked away, fifty years later, the same federal government that had promised not to interfere with the Dene way of life was left with the cleanup.

The effort to remediate the mine site is being led by Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, the present-day version of the department that quashed Kay’s roasting objections back in 1949. The long-term strategy, for now, is to decontaminate the surface area (remove buildings, scrape away soil) and to freeze the 237,000 tonnes of arsenic trioxide dust in place underground, entombing it until somebody comes up with a better plan.

Last July, the remediation began in earnest. In the fall, weeks of blasting took place at the site, laying the groundwork to install thermosyphons, massive tubes that will use passive heat exchange to facilitate the underground freeze. Just before the writ dropped for the 2021 federal election, the government signed a series of agreements with the Yellowknives Dene. These agreements are not final settlements—rather, they are intended as the opening framework for the apology and reparations. “We’re still at the very beginning,” says Lena Black, acting CEO of the Yellowknives Dene. “This is the gate.”

The agreements will allow for negotiations along three parallel tracks. The first will be about direct compensation and a formal apology. The second will be aimed at supporting programming for a community whose social outcomes today are worse because of the mine—housing, mental health and addictions treatment, education and training, infrastructure. And the third focuses on the billion-dollar remediation work. This is to ensure that the Yellowknives Dene are not left out of the big government contracts being awarded for tasks like building the underground freezing apparatus or dismantling contaminated buildings on the site. Done right, the process could be a holistic attempt to repair and make amends for the damage done.

With the broader framework for negotiations in place, the First Nation will hold consultations about what members might want in an apology and compensation. Black doesn’t like to speculate about what her fellow citizens will want or need or what a consensus, if one can even be achieved, would look like. “That is going to be a very long process for us, because all of our members have a lot to say,” she says.

Scholars of apology say that, to be meaningful, an apology must include an acknowledgment of the offence given or the harm done as well as a sincere expression of remorse, shame, and humility. In 2009, Pope Benedict XVI offered “sorrow,” “sympathy,” and “prayerful solidarity” for the victims of abuse at Canadian residential schools, but despite the Catholic Church’s role in administering many of the schools, he did not use the word “apology.” West German president Richard von Weizsäcker’s 1985 speech, on the fortieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe, is often held up as a model. Von Weizsäcker included a blunt recitation of the era’s horrors, not only “the 6 million Jews who were murdered in German concentration camps” but the slaughters of Sinti and Roma people, of gay men, of the mentally ill, of hostages, and of members of the resistance movements in occupied countries.

Recent institutional apologies have not always aged well. In 2008, then prime minister Stephen Harper gave a formal federal apology for Canada’s residential schools. Initially, it was broadly well received, but as political scientist Glen Sean Coulthard writes, that goodwill has “since dissipated.” Coulthard, who is Yellowknives Dene, argues in his work that these sorts of apologies tend to be too limited in scope: they address an “event” rather than a “structure.” It’s a paradox: a colonial state, in a way, apologizing for its mode of being while continuing to be that same colonial state.

What might an effective apology for Giant Mine look like? It would need to acknowledge not just the arsenic infecting the land, but that the land has never been ceded, that it was taken and pillaged for profit, and that the harm done still ripples outward today. Psychiatrist Aaron Lazare, whose book On Apology is a touchstone for the field, notes one other important thing that the offended party needs from an apologizer: “Assurances that they are safe from further harm by the offender.”

But, at Giant, the possibility of further harm looms large. It’s difficult to apologize effectively when the damage is ongoing and may yet get far worse.

The worst-case scenario at Giant Mine is grim to contemplate. Here is an attempt. If the underground storage chambers were ever to rupture or flood and spill their contents into Great Slave Lake, whose shore is frighteningly close by, it’s not just the lake that would be poisoned. The 1,700-kilometre-long Mackenzie River it feeds would be contaminated too. The Mackenzie, in turn, leads directly to the Beaufort Sea and the Arctic Ocean. “We are going to be the ones who die first,” Black says of the possibility of a catastrophic rupture. But “all the waters are connected.” Imagine if toxicity on the scale of Chernobyl or Hiroshima were portable: if it could flow outward, like a waterborne virus, rather than being relatively contained within a knowable fallout zone. The Yellowknives Dene wouldn’t be the last to die.

And the risk will never subside. Unlike, say, nuclear waste, arsenic trioxide does not have a half-life. Its toxicity will not ease with the passing of centuries. As Sandlos, Keeling, and their collaborators wrote in a 2019 paper, the arsenic “will remain a toxic threat for eternity if technology is not developed to remove it from the site.”

In the nuclear age, scientists, linguists, and others have grappled with a related problem: How do we warn future generations—future civilizations, even—about the radioactive waste we have left behind? When history might be erased and languages might be reinvented, how do we tell the people of the future not to dig any deeper? In his book Underland, British nature writer Robert Macfarlane describes some of the suggestions proposed by a US-run panel of experts for a nuclear waste site in New Mexico. They included terrified human faces carved into stone (Edvard Munch’s The Scream was a possible model) and what Macfarlane called “a durable aeolian instrument” for tuning “the far-future desert winds to D Minor, the chord thought best to convey sadness.”

Others theorize that the only certain way to communicate the dangers of these sites to a distant future is through storytelling. One scholar has proposed the creation of an “atomic priesthood” whose eternal task is the dissemination of folklore about nuclear waste. As Macfarlane writes, “In this way what began as a simple set of warnings might be reconfigured as, say, a long poem or folk epic, made narratively new for each society in need of warning.”

At Giant, future civilizations would need more than a warning. They would need to understand how to keep something like the perpetual freezing technology running safely. So, while the challenge for a properly sealed nuclear waste site is to keep people from snooping at it for 10,000 years or so, the challenge at Giant is to pass on something both more durable and more detailed than a simple warding away. Sandlos and his co-authors believe that the solution might be to spread knowledge about the mine site rather than to instill fear of its presence. “The Elders remind us that our duty to warn the future is also a responsibility to acknowledge and remember the past,” they write. They suggest that tools like tours of the containment workings, ongoing annual ceremonies, and a visitor information centre that explains the “monster underground” might stand in as Giant’s version of an atomic priesthood.

What is my own role in all this? In On Apology, Lazare writes that, “if we can be proud of national accomplishments not of our making, so, too, must we accept shame for national misdeeds not of our making.” I know how to feel about the fact that the government of Canada could have shut Giant’s roaster down in 1949 but didn’t. It was an appalling decision, one that prioritized profit over human lives. But I am less certain how to feel about my own family’s responsibility. If he’d lived longer and learned more, would my grandfather have found his way to regret? What does all this mean for those of us who were only children or who were born years and decades later?

Maybe this is my path forward. Maybe the only meaningful atonement I can offer is to write my own story about Giant Mine and pass it on.

Correction April 26, 2022: An earlier version of this article stated that confusion over Treaty 11 meant that land was taken from the Yellowknives Dene First Nation without their consent. In fact, the Yellowknives Dene are signatories to Treaty 8; Treaty 8 and Treaty 11 both led to land being taken from signatory nations without their consent. The Walrus regrets the error.