In 1984, the year I turned eight years old, my father was diagnosed with nasopharyngeal cancer.

Before he moved to Canada, at age thirteen, he had lived with his mother and three older sisters in a two-room house in a community, the name of which, translated into English, is Lone Tree Village, one of many small towns in China’s Pearl River delta. There, his neighbourhood of winding alleys and stone houses was built around central communal spaces: the well, the pig pen, the fire pit, and, most famously, the giant tree in the main square with its drooping, heavily canopied branches. I was told that their home’s main source of heat was a coal-burning stove that, after generations of use, had coated the walls with a thick black layer of sticky dust. My father’s illness, a particularly difficult cancer, was one that was seen in a high number of Chinese men of his generation who spent their childhoods in heavily polluted southern China, where foods preserved in salt were linked to a higher risk of developing nasopharyngeal cancer.

When he coughed at night, it was constant. If he slept, or if my mother slept beside him, I still don’t know.

Also in 1984, and not coincidentally, I read Anne of Green Gables for the first time.

Like most of my books, this one came from the shelves in the dining room, where my four older sisters would leave books they had already finished. The Norton anthologies. Scruples by Judith Krantz. Surfacing by Margaret Atwood. I owned very little that was mine alone; it seemed like everything, from the frames of my glasses to my banana-seat bicycle, had been used by my sisters before me. I was used to reading, and mostly abandoning, their books. Some were too sexy. Most were from their university English courses. But this boxed set containing the first three Anne books, with its illustration of a thin, sad-faced little girl, seemed meant for me. I was thin, and I was a little girl who was continually left alone, who worried about cancer and chemotherapy, and whose face in the mirror was almost always sad. Maybe this book could be mine.

Scrappy, red-headed Anne Shirley, along with hockey players and maple syrup, may very well be Canada’s most famous export. Tourists flock to Cavendish, PEI, Lucy Maud Montgomery’s hometown and inspiration for the fictional Avonlea. Anne of Green Gables—The Musical has been in perpetual production since 1965 in Canada, of course, and also toured in Tokyo and London. Screen adaptations crop up every generation, each slightly different but mainly telling the same story of Anne’s abandonment, adoption, and propensity for mishaps, both domestic and social.

By the time I started reading the novels, in 1984, Anne had become a lucrative industry, in the same way that the Harry Potter series by J. K. Rowling once dominated entertainment, travelling far beyond the books themselves and spawning films, stage plays, even a theme park in Japan. Both Anne and Harry are orphans, dealing with grief and loss and a world that seems to value them less than it does children with two living, affectionate parents. People love underdogs, but more specifically, child readers, with their sensitive minds and developing emotional intelligence, often love to be immersed with fictional children who have suffered the biggest of losses: the deaths of their parents. Think of Mary in The Secret Garden, Oliver in Oliver Twist, Mowgli in The Jungle Book. It’s a kind of grim reassurance. If these orphans could go on to accomplish great things and experience love in other forms, then maybe all children have the chance to try again, to behave better, to be happy. Or, at least, that’s what I believed.

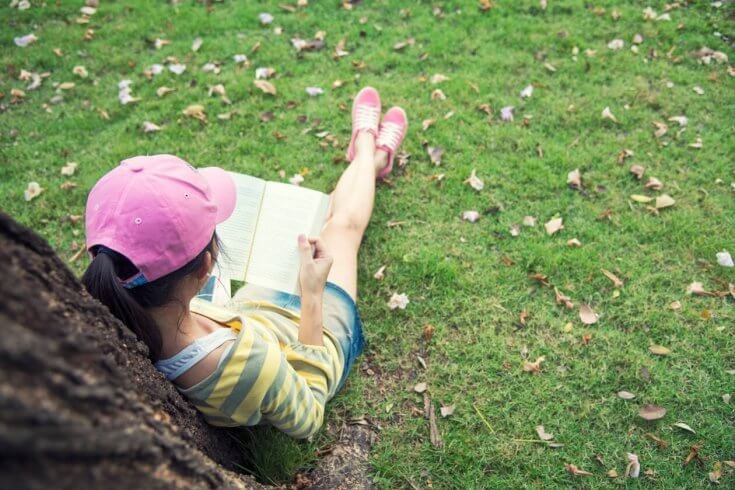

My older sisters, tasked with the job of keeping me distracted while my father underwent surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, bought me the rest of the Anne series, in small paperbacks that cost $3.50 each. That winter, I read through them all once, then read through them again, curled up on my bunk bed, my desk lamp twisted backward during dark afternoons after school. My mother was rarely home from the hospital before five, when she cooked dinner in a fury before leaving the dishes for Emma, who was fifteen and had a Billy Idol–esque spiky haircut, and me. At 6:30, with Pam and Tina, my two middle sisters who, by then, were in their twenties, she returned to the hospital until visiting hours were over.

When they came home, I was often already asleep, books on the floor beside me, spines cracked at the passages I had read over and over. I have my old copy of Anne of Green Gables even now, and it always falls open at page 203, where Anne meets her mentor and teacher, Miss Stacy, who sees Anne’s passions as an asset and who encourages her to perform and write. “We have to write compositions on our field afternoons and I write the best ones,” Anne tells Matthew and Marilla, the middle-aged brother and sister who have adopted her. I never spoke of my school accomplishments at home: the short story that won the school contest, the spelling bee, that one time I performed more sit-ups in a row than anyone else. These were small successes that only made me feel valued for a day, maybe two, before I remembered that there were darker, more important things to worry about.

My mother didn’t say much, caught as she was in a tornado of doing, caring, and surviving. She had come to Canada to be a bride in a marriage that was not entirely arranged but not entirely of her own choosing either. In 1958, the year she arrived, people in Hong Kong were looking ahead to the day in 1997 when the colony would cease to be part of the Commonwealth and be returned to China’s governance. I grew up hearing stories of women like my mother who looked for potential husbands that could get them far away from the looming threat of Communist China. My father, a Canadian citizen whose family was firmly established in Vancouver but whose origins were in a small Chinese village close to where my mother’s family also had their roots, seemed like a wise choice. He was handsome, employed, and wrote charming letters after their two mothers had made introductions through photographs sent in white-and-blue airmail envelopes. That was enough for my mother to believe she was in love, board a steamer for the very first time, and move to Vancouver.

My mother married and had five daughters and never worked in any job for more than a year. Her opportunities for learning English were limited, and by the time I was born, my sisters were old enough to earn their own spending money, and my father’s salary as an accountant negated the need for my mother to work outside the home. Her English fluency diminished, and she grew uncomfortable speaking it at all. When I was six, I remember my father and I convinced my mother to enroll in an English-conversation class. At the time, she had registered me for Chinese school, which I hated, on Tuesday and Thursday afternoons. The teachers taught us by rote, repeating sentences in Cantonese over and over again, their rulers banging out a relentless rhythm on the chalkboard.

“If I have to go to Chinese school,” I declared, “then you have to go to English school.”

My father laughed, pointed at my mother, and said, “Jenny has a point.” Later that week, he pulled out a catalogue of night courses and circled the English class that was running at the high school three blocks away. As he dialled the number to register my mother, he nodded and said, “So convenient. We should have thought of this years ago.”

I can still picture my mother sitting at the kitchen table with a cup of tea, staring into middle distance, her face folding in on itself as if she were about to cry.

She lasted two evening classes before dropping out. “The teacher hates me,” she shrugged. We never spoke of it again.

My father became the husband who filed the taxes, completed the forms, and met with the teachers, while my mother stayed where she felt safe: in our home and in the shops of Chinatown.

Years later, long after I was an adult, my mother told me that, while my father was fighting his cancer, she spent long nights worried about what would become of her in a country whose languages she did not speak and whose systems were unintelligible to her. She was a woman who had married at nineteen, who had never lived alone, who had been coddled by her mother because she was the pretty daughter with the pretty singing voice. Growing up, my sisters and I left her out of our conversations about school or work or the latest episode of Knots Landing. When we watched television, she stayed in her bedroom, where she listened to Canto-pop cassettes her sisters-in-law sent her from Hong Kong. Back then, I watched the fear creep across her face whenever a stranger spoke to her in English—a bus driver, a sales lady at Woodward’s, the mailman. Rather than answer, she pushed me in front of her so I could translate both the language and the social codes. When my father stayed overnight at the hospital, I could hear my mother weeping. I heard her. As clearly as I heard my father’s rattling cough when he was home.

In Anne of the Island, Anne, on a break from her studies at Redmond College, visits her birth home in Bolingbroke, where her parents, a young couple named Walter and Bertha, were schoolteachers. It’s a “shabby yellow house in an out-of-the-way street” where a woman gives her a bundle of letters—found in the closet upstairs, tied with a faded ribbon—that Walter and Bertha had written to each other over the course of their courtship. Through these letters, Anne discovers that her parents were very much in love, that she was a deeply anticipated baby, and that their family was, in the brief time they were all alive, as flawless as a family could be, good people who lived good lives. They were very much in love and well liked in their community. They had plans for the future. And, most importantly, they had wanted Anne.

Although this scene in Anne of the Island is brief, it’s hard not to feel a pang of pity for Marilla, who is first described in Anne of Green Gables as, “a woman of narrow experience and rigid conscience.” Marilla is certainly not beautiful or young or in love, and Anne never imagines a romantic narrative about her past, as she does about Bertha. Marilla believes in hard work, in a decorous life, in plain Protestant virtue. She denies Anne a puffed-sleeve dress, until Matthew goes ahead and buys one for her himself. Anne often turns to other women, pretty, younger women, like Miss Stacy and Mrs. Allen for advice.

In the end, however, Marilla becomes the mother that Anne has always needed, a firm ballast whenever Anne finds herself lost in a tumble of emotions. And, in that process, Anne softens Marilla’s angles so that she permits laughter, sadness, and empathy to escape her thorny exterior. In the books, motherhood—the real, working motherhood—isn’t pretty. While Bertha might have been beautiful and expressive, she isn’t the one who is able to give Anne stability or education or a moral centre. It’s Marilla, the spinster with a broken heart who lives with her bachelor brother, that does that. It’s Marilla who encourages Anne to attend university at a time when most young women didn’t. It’s Marilla who travels to care for Anne during the births of her children.

Growing up, I had many substitute mothers, women I turned to for the kind of comfort and understanding my mother, terrified for her husband and the life he had built for her, could never provide. During the years my father was sick, I remember there was Sue from church who listened to my worries. There was my friend Klea’s mother, Margueritte, who let us doodle on a designated living-room wall. There was Mrs. Carleton from school who called me her “talented little writer.” When my mother used up all her energy in caring for my father, managing our family, and, later, fighting a deep depression that lasted my entire adolescence, it was these women who hugged me, told funny stories, and said I was doing okay, even if it was abundantly clear that I was not. It was Sue who cleaned the wounds on my shins, where I was scratching the skin raw, my insides wound so tight with anxiety that I wanted to break open the surface of my body with my fingernails to release the tension. I saw myself in Anne. But I saw other, more perfect, mothers everywhere.

Marilla, in the beginning of Anne of Green Gables, before we know what she is capable of giving Anne, was my mother in novel form: flawed, unable to accurately express the roil of emotions under the skin, defined by rules. When my mother was at home, it seemed like the only words she spoke were orders about meal prep or laundry, or she would sometimes rage about small mistakes: a ball of hair in the shower drain, spilled juice in the fridge, a hole in the seat of my pants from climbing a tree. I don’t remember her asking us how we were doing, what school was like, if we were seeing our friends. Like Marilla, she seemed to care nothing for fashion or her daughters’ feelings.

Now I know she was grieving and scared, unable to break out of her anxiety to see that the lives of her daughters were continuing, despite my father’s cancer. But, at eight years old, confused and worried, I needed the comfort of knowing that not all mothers were perfect, but that, maybe, eventually, they might say the loving words their children needed to hear. It was okay that they weren’t all tolerant and pretty and interested in the small lives of their children. Sometimes they didn’t speak English. Sometimes they collapsed in bed without saying one word to their youngest daughter, pulled the covers over their head, and cried themselves to sleep.

Near the end of Anne of Green Gables, Marilla, changed by years of parenting, opens up to Anne. “You blessed girl!” she says after Anne decides to stay home and delay her university education. “I feel as if you’d given me new life.” In a few years, I hoped, my own mother might say something just like that.

I remember one afternoon two years later, my mother saw me reading on the couch, angled so the dim light from the table lamp illuminated my copy of Anne of the Island, the Anne book I had reread the most, chiefly because of her romantic interests, (this was a fantasy that my nascent boy-crazy brain was just beginning to find exciting). From the kitchen, she glared at me and yelled, “How long have you been reading that?”

I couldn’t remember, but it had likely been ever since I had come home from school. “I don’t know,” I mumbled.

“Stop reading and help me cook dinner.” My mother pointed her spatula in my direction. “Now.”

“No,” I said. I calmly continued to read.

Without saying another word, my mother, furious and almost certainly emotionally and physically exhausted, marched into the living room and pulled the book out of my hands. Then I followed as she walked into my bedroom and swept all of my Anne books off their designated shelf.

“Stay here until I come back,” she barked. I did as I was told. From the doorway, I could hear her moving objects in the kitchen, muttering as she dragged a chair across the linoleum floor. I had only been reading, something I had been doing for months, alone and undisturbed. Waiting, I tried to remember the last time my mother had noticed anything I was doing. And I couldn’t.

When she returned, she said, “I hid them. You’re not getting them back until you help me cook dinner.”

In the kitchen, she stood at the stove, at a blazing hot wok. Instead of standing beside her so I could watch and therefore anticipate what ingredient she needed next (something I had watched my sisters try, with mixed success, for most of my life) I sat down on the floor with my back against the refrigerator. I had no plan, I only knew that I was angry, and if I couldn’t have what I wanted, my mother wouldn’t either. When my mother turned around to open the fridge door for a bottle of oyster sauce, I was right there, staring at her.

“What are you doing? Get up. I need the fridge.”

“No. I’m not moving.”

“I don’t understand.”

“I’m not moving until you give me back my books.”

What my mother likely hadn’t considered until that moment was that my books, and my Anne books in particular, were the constants in my life. My oldest sisters were trying to manage my father’s insurance and health benefits. My sister Emma was a teenager, spending most of her free time in the weights room at the high school, where building muscle mass seemed a way to control at least one thing when everything else was uncontrollable. My grandfather fell into a quiet depression, spending more and more time in his room off the hallway as his only son grew sicker and sicker. There was very little time for anyone in our household to pay any attention to me. I walked to and from school alone. I completed my homework alone. I was a talkative, restlessly social child, who chatted nonstop at school (I remember my report card that year said, “It’s a challenge for Jennifer to understand that sometimes her input isn’t appropriate”). As soon as I entered our house, the silence enveloped me, and I hated it.

Like me, Anne Shirley was a talker, a child who craved affection and human connection, even from the adults who would never love her. Before she arrives in Avonlea to live with Marilla and Matthew, she creates imaginary playmates at the orphanage and the one family home where she was treated more as a nanny than an adopted child. In Avonlea, she finds her true family and is loved and celebrated for the sensitive, creative, and passionate little girl she is, not the decorous, quiet little girl Marilla might have once wished for.

Matthew, near the end of Anne of Green Gables, says, “Well now, I’d rather have you than a dozen boys, Anne. Just mind you that—rather than a dozen boys. Well now, I guess it wasn’t a boy that took the Avery scholarship, was it? It was a girl—my girl—my girl that I’m proud of.” In my own small, dark place, worried that my father would never get better, that I had ruined my parents’ last chance to have a son by being the fifth and youngest girl, this affirmation was what I needed, even though it wasn’t about me. This comfort was what I turned to, again and again, when there was no one to notice what I had eaten for my after-school snack or to read my most recent short story. In that kitchen, while the winter rain rattled the steamed-up windows, the injustice of having this comfort stolen from me lit an intense rage.

I remember my mother stood in front of me. I knew she was thinking of pushing me aside, something that would be hard for her if I were determined to hold my ground. At ten years old, I was already at my mother’s height. Her parenting style had always been strict and unwavering, with very little concession made for the wishes of her children. But I also knew my father was, at that very moment, lying in a hospital bed, a thin curtain separating him from another man who was succumbing to a brain tumour and who cried for his sons long into the night. My mother spent most of her waking hours brewing medicinal soups, hoping something might help, and bringing them to my father in a green Thermos. She brushed his teeth, trimmed his nails, held him upright when he sat on the toilet.

This was not the moment to fight.

She pulled a chair from the table, climbed on the seat, and opened a high cupboard, where my books were piled behind a stack of rice bowls. She dropped them, one by one, onto the floor. Anne of Green Gables. Anne of Avonlea. Anne of the Island. Anne of Windy Poplars. Anne’s House of Dreams. Anne of Ingleside. “There,” she said quietly. “You win.”

In later books, Anne learns to control her passions, to muffle her temper, to wear fashionable clothes. When I was eight, this seemed like success to me, or at least a success that I understood. That year, I began having panic attacks at school, for reasons that were seemingly unrelated to my father’s illness. I remember one morning, I arrived at my classroom after the bell had rung. I panicked in the cloakroom, hyperventilating behind a row of coats, crying and thrashing so hard that my teacher had to hold me to keep me from accidentally punching the walls. One afternoon, that same teacher read aloud stories we had written, and the bell rang before she got to mine. I burst into tears and didn’t stop until she pulled me to her in a tight hug, once again holding me so I could not hurt myself as my body tried to kick out its frustrations. I remember she wrote a letter to my parents. “We are working with Jennifer to help her learn that not every small mistake is a catastrophe.” After that, I visited our school counsellor every week in a corner of the library, where I was allowed to pick from a table of toys while she asked gentle questions about what scared me and what I liked about myself. “I’m good at school,” I said. I remember that she paused with a Jenga block in her hand. “Is that what you like about yourself, or is that what everyone else likes about you?”

What I wanted most was to no longer worry, to no longer panic that one tiny misstep would unleash a chain of disastrous events, leading, as all of my panic attacks led, to a dystopian daydream of my family being torn apart. Sometimes I feared death. Sometimes I feared that my sisters would be kidnapped. Sometimes I imagined a man in a black top hat slowly walking up the sidewalk toward our house. What he would do when he arrived was amorphous, a shapeless cloud of evil. But I knew he would destroy everything and we would be separated, never to find each other again.

At eighteen, Anne starts university and dreams of becoming an author, but in the end, sets aside her ambitions to marry Gilbert Blythe and raise six children. It is her son Walter who becomes the world-famous writer, after he is killed in battle in World War One and one of his poems, about the cost of war and reminiscent of “In Flanders Fields,” is read around the English-speaking world. Anne channels her creative energy into her family. She no longer has her rage or any true passions outside of domestic life. She gardens. She mothers. She tells stories to her children.

This calmness, the possibility of becoming an adult without dark thoughts, with a beautiful home and the kind of family that the world recognizes as valuable and worthy of praise, was a fantasy I buried myself in every single day. One day, I wouldn’t care if anyone read my stories or not. One day, I might marry a doctor like Gilbert, who would know what to do if anyone fell sick. One day, I could shape a noisy, affectionate, tightly bonded family of my own. And then there would be nothing left to fear.

In 1988, the year I turned twelve, my father died.

I answered the phone when our family doctor called and asked to speak to my mother. It was a Saturday morning in September, and I was getting ready for Chinese school, which I was still attending, six years after my mother had dropped out of her English classes. I remember the doctor called my mother weekly, explaining to her the details of my father’s treatments in Cantonese, which the oncologist at the hospital didn’t speak. He didn’t usually phone on Saturdays, but I didn’t think of what a weekend call might mean, only passed the phone to my mother silently as she packed another day’s worth of food for my father, which, by then, he rarely ate. If he tried, he would usually throw it back up before tearfully apologizing. “I’m sorry,” he would whisper. “It’s such a waste.”

I remember my mother listening with the receiver pressed against her ear. I remember her wailing for my sister Tina before she dropped the phone and collapsed in a heap on the kitchen floor. We were at the hospital in half an hour, huddled in my father’s room with a nurse and the family doctor.

I have replayed that moment many times in my life, that hour we spent with my father’s body in a palliative-care ward at Mount Saint Joseph Hospital in East Vancouver. It was a small room, with one tiny closet that fit one change of clothes and a coat. There was a television mounted in a corner near the ceiling. The curtains were open, and it was sunny. In the bed, I remember my father was lying partially upright, as he had been doing lately to lessen the constant ache in his throat. His skin was grey and yellow at the same time, an impossibility in life and an unmistakeable sign of death. His mouth was open, as if he had died while calling out in pain, as if he had been calling out for us—his five daughters, his wife, anyone who remembered him from before. When he was a teenage boy walking the Stanley Park seawall with his father. When he was handsome young accountant in a glen-plaid suit with the pretty wife who sang Doris Day songs in her pretty voice. When he was a father and taught his girls to play badminton and to never, ever rely on a man for their livelihoods.

My mother held his face in her hands and wailed, “What were you trying to tell me?” I turned away then and began to empty his closet into a plastic Safeway bag I had found on a shelf. A nurse gently took the bag away from me and whispered, “Don’t worry about that.” But I did worry. Because worrying was what I had always done best.

For years afterwards, my mother slipped in and out of a deep depression. She spent the bad days sitting on the sofa with the living-room curtains drawn tight, staring at the shut-off television, sometimes crying, sometimes silent. On good days, she made me elaborate breakfasts with ham and eggs and hash browns. On most days, good or bad, she stayed home. If she talked to me, she started crying, so I avoided her as much as possible.

In those years, my anxiety was relatively quiet. My father had already died. My mother left me almost entirely alone. My sisters moved out, one by one. There were weddings. As a teenager, I no longer wanted to be the adult Anne, the wife of a respectable doctor. Instead, my brain was filled with Kurt Cobain and Keanu Reeves, Gwendolyn MacEwen, and Sylvia Plath. If I wanted to be anyone, it was an amalgam of Winona Ryder, Betsey Johnson, and Margaret Atwood.

And yet I turned to Anne every few months, on long nights when a Sinéad O’Connor song wasn’t enough, on nights when I acutely missed my early childhood, those years when my father brought us a box of long-johns after work, when we all piled in the copper-coloured station wagon and went to White Spot for dinner, where my father would order the chicken pot pie.

Near the end of Anne of Green Gables, Matthew dies after reading about the collapse of the bank where he had invested the family’s savings. This chapter—in which Anne is unable to cry and she and Marilla have to reorganize their lives without Matthew and without money—was the one I read over and over, weeping at his death and the aftermath. Even then, as a teenage girl, I knew that when I cried reading about Matthew, I was really crying for my father.

In the years that followed, my anxiety would spike and wane, and at its worst, when my marriage was ending, I experienced panic attacks up to seven times a week. The promise of a peaceful, contented life, in a big house, surrounded by children, never materialized for me, even when I lived in a big house and was a stay-at-home mother. When it came time for my ex-husband and I to divide our library, I found all of my Lucy Maud Montgomery books in a box in the basement, and read them, yet again, at the age of thirty-eight. I was shell-shocked, sleepless, and worried about how my son and I would survive, but I slipped into Anne’s story as easily as I ever had.

The last Anne book, Rilla of Ingleside, chronicles World War One, with all three of Anne and Gilbert’s sons enlisting as soldiers. Jem and Shirley return, but Walter dies in battle. Rilla, Anne’s youngest daughter, fears she has lost her sweetheart to war also, after communication stops between them. In the end, he comes back for her, a white scar running down his face, and the promise of love is hers again. An older, traumatized love but love nonetheless.

Newly separated and raw, I read this and cried. I realized then that this happy ending of Anne’s was no happy ending at all. War had scarred or taken each of her children. Her red hair, the one part of her body that spoke to her unruly emotions, turns white. Her happiness as a wife and mother, it seems, was temporary, and no defence against death and war. Anxiety, for me anyway, is often about searching for the magical one thing I could do to make everything better, even when I know that often there is no solution, no list I could make or email I could write that would change the outcome. The idea that Anne could only earn her peaceful happiness for so long, by suppressing her anger and ambitions and wandering brain, was a comfort far different from the comfort I sought as a child. Even she, the irrepressible Anne, couldn’t stop the war from coming. There was nothing she could have done, in the same way there was nothing I could have done to prevent my father from dying and nothing I can do now to change the decisions I made during the last years of my marriage. Acceptance, perhaps, is the antidote whenever we fear disaster.

Anne lost her birth parents and, later, a child. She was an orphan who was given a second chance with a loving family and a community who accepted her shortcomings and celebrated her successes, with a husband and children who adore her. And then, in the end, she loses her son, her life bookended by mirrored traumas. Her happiness rises and then falls again. Like mine. Like yours. Like everyone’s. Anne, it seems, has stayed with me almost my entire life, different parts of her story fitting into my troubles like a key in a lock.